Modern Chinese poetry begins with its turn away from classical Chinese poetry in the early twentieth century. This turn saw the adoption of the vernacular and the move away from classical forms. Yet the history of modern Chinese poetry does not mimic the trajectory of Western modernist and post-modernist experimentations. In particular, the years between the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 represent a hiatus in the development of modern poetry in mainland China. The death of Mao and the ensuing end of the Cultural Revolution saw the resurgence of poetry away from the officially sanctioned poetry of the Mao era.

It was during this period in the late 1970s and into the early 1980s that the first experimentations in contemporary poetry from mainland China emerged. Dismissed as the Misty group by critics unreceptive to their imagery and language, these poets were nevertheless the first to be translated and anthologised in English-language anthologies of contemporary poetry from China. In the decades since, several competing aesthetic movements have emerged that represent a move away from the imagery and language of the Misty poets. At the same time, anthologies in English translation have continued to chart this ongoing period even if ‘for two decades contemporary poetry from China was almost exclusively represented by Menglongshi (Misty Poetry) (Yeh ‘Modern Chinese Poetry’ 603). These anthologies even now mostly emanate from the larger metropolitan centres of the Anglophone world. Recent anthologies include W. N. Herbert et al’s 2012 Jade Ladder: Contemporary Chinese Poetry, published by British poetry publishing house Bloodaxe Books, Ming Di’s 2013 New Cathay: Contemporary Chinese Poetry from the American independent literary Tupelo Press publishing house, and Liang Yujing’s 2017 Zero Distance: New Poetry from China from the American experimental Tinfish Press publishing house.

Australian translations of contemporary Chinese poetry have also been forthcoming in the latter part of the twentieth and early part of the twenty-first centuries. Important work in the translation and dissemination of contemporary Chinese poetry has come from such scholars and literary translators as Mabel Lee, who in 1990 published Yang Lian’s The Dead in Exile (Tiananmen Publications) and Masks & Crocodile: A Contemporary Chinese Poet and his Poetry (Wild Peony Press). Her 2002 translation of Yang Lian’s Yi appeared through the American publisher, Green Integer, while her 2014 translation of poet and writer Hong Ying’s poetry collection I Too Am Salammbo (2) appeared through the Sydney and Tokyo-based Vagabond Press in its Asia-Pacific series. Lee is also the editor of the 2014 Poems of Hong Ying, Zhai Yongming & Yang Lian (Vagabond Press) and along with Naikan Tao and Tony Prince is one of the translators. The latter two also published in 2006 Eight Contemporary Chinese Poets (Wild Peony Press). Finally, literary translator and critic Simon Patton has co-edited the China domain of Poetry International Web, and is the translator along with Tao Naikan of avant-gardist Yi Sha’s 2008 Starve the Poets! Selected Poems (Bloodaxe Books).

Poet, writer, essayist, editor and translator Ouyang Yu has over a period of three decades since his arrival in 1991 from mainland China to pursue a doctorate at La Trobe University brought to the notice of the Australian literary establishment contemporary Chinese poetry through his ongoing translation projects. Some of his translations have acquired canonical status in Australian literary culture through their inclusion in such publications as the Best Australian Poems anthologies (Black Inc). His translations of Shu Ting’s ‘Good Friends’ and Shu Cai’s ‘Absurdity’ appeared in Best Australian Poems 2012, edited by John Tranter, while his translations of Bai Helin’s ‘Meeting with the Same River’ and Hu Xian’s ‘The Orchard’ appeared in Best Australian Poems 2013, edited by Lisa Gorton.

Ouyang Yu has translated and edited into English two major anthologies of contemporary Chinese poetry. In Your Face: Contemporary Chinese Poetry in English Translation was published in 2002 through the literary journal, Otherland, as a special issue of the journal, and Breaking New Sky: Contemporary Poetry from China was published in 2013 through poetry publisher Five Islands Press. With a few exceptions, both of these publications, like other English-language anthologies of contemporary Chinese poetry, concentrate on poets who either emerged or were born after the death of Mao in 1976. They also define contemporary Chinese poetry in its broader sense to include poetry from the wider Chinese world, including in the case of In Your Face from the diasporic world of Australia.

Apart from his two major anthologies in English translation of contemporary Chinese poetry, Ouyang Yu continues to publish translations of contemporary Chinese poetry and maintains an active connection to contemporary Chinese culture through his teaching and research in mainland China. In 2016, he edited in journal form along with poet and short-story writer Yang Xie ‘A Bilingual Selection of Poetry in Chinese and English’, translated by Ouyang Yu. It features a selection of twenty-one contemporary Chinese poets with forty-six poems. In 2017, he published his translations of three contemporary Chinese female poets in Poems of Wu Suzhen, Yue Xuan & Qing Shui (Vagabond Press). He also engages in what he calls ‘self-translation’, as marked by the publication of his 2012 Self Translation (Transit Lounge) of his translations into English side by side with the Chinese of poems written originally by him in Chinese but translated into English as discrete English-language poems.

Ouyang Yu is also a major contributor to Australian literary culture through his own poetry, fiction, and essays. In his 2009 Barry Andrews Memorial Address, Nicholas Jose notes Ouyang Yu’s ‘original and polymathic contributions to China-Australia literary interaction’. Moving fluidly between cultures and languages, Ouyang Yu has developed a dynamic aesthetic in his work that ‘enables him to move surprisingly between Australian attitudes and Chinese perspectives’(3).

Ouyang Yu’s work as a literary translator functions as a bridge between China-Australia literary cultures. Yet In Your Face received little critical attention upon initial publication. Ouyang Yu describes how it ‘was sent to nearly all the major literary journals and newspapers in Australia but got no response whatsoever (although it has since been reviewed in a number of magazines, notably Overland)’ (‘Motherland, Otherland’ 53). On the other hand, Breaking New Sky received critical attention in such online literary journals as the poetry-focused Cordite, Mascara, and the writing journal TEXT. (3) Anthologies such as Ouyang Yu’s not only bring closer together Australia-China literary relations but also join Australian literary culture to the international stream of English-language translations of contemporary Chinese poetry. A marker of the importance of his work in the translation and dissemination of contemporary Chinese poetry is Cosima Bruno’s inclusion of In Your Face along with publications by Mabel Lee, Tony Prince, Tao Naikan and Simon Patton in her appendix of book-length translations into English of Contemporary Chinese poetry from 1980–2009 (280-285).

Anthologies of poetry in translation carry images of the originating culture that can challenge a target culture’s preconceptions. In the case of China, images of China remain ambiguous in the broader Australian imagination. The question becomes what image of China emerges from Ouyang Yu’s selection of poets and poems across these two anthologies minimally divided by time being only eleven years apart and which span between them a significant period of China’s modernisation. This question does not ignore the aesthetic drive of contemporary Chinese poetry but adds a layer of interrogation. The question applies to any anthology in English translation of contemporary Chinese poetry, but Ouyang Yu’s anthologies circulate within the Australian critical field and therefore merit analysis within the networks of Australian literary culture.

To readers and critics who see the role of anthologies as being one of canonisation of poets and poems, Ouyang Yu throws a challenge when he states in his introductions to In Your Face and Breaking New Sky that they are eclectic and personal collections. He states in In Your Face that his interest does not lie in circulating established names but in discovering what ‘lies about us abundant, abandoned and not yet appropriated’. This is not to say that poets already known to western readers are not among the poets featured in In Your Face, but it includes lesser-known names. In Breaking New Sky, Ouyang Yu is even more provocative when he proposes the radical notion that ‘I have always wanted to publish an anthology of poetry featuring poems without their authors’ names attached to them’.11 He seeks to publish only those poems that have moved him ‘emotionally or cerebrally’. He is not interested in canonisation but enjoyment.

In not delineating the field of contemporary Chinese poetry and setting its boundaries within strict limits, Ouyang Yu opens up the play of contemporary Chinese poetry beyond his taste to that of the reader. If he has made ‘many discoveries’ (Breaking New Sky,8) then the reader may, too. He does not eschew a general positioning of contemporary Chinese poetry in his introductions, but he does not categorically define readers’ tastes for them by circumscribing the possibilities of contemporary Chinese poetry even as he is resolute about what he does not like. In In Your Face, he includes few poets born before the 1950s, because he ‘can hardly read the old ones’, but he reminds readers that several, including him, were born in the 1950s, ‘such as Wang Jiaxin and Ouyang Jianghe, once dominating voices in the Chinese poetic scene now banished to the periphery by the rise of the new-generation poets’. We might compare Ouyang Yu’s playful introduction in In Your Face with that of the anthologists of Jade Ladder, when Yang Lian argues that ‘in this anthology, we hope to rebuild the formal values of poetry’, and ask ourselves whether the Jade Ladder anthologists and Ouyang Yu are that far removed. Enjoyment also means enjoyment of poetry as art form.

Ouyang Yu’s statement in Time magazine in 2010 that ‘poetry is one of the freest media in China, but the West doesn’t know it’ is intriguing when we consider ‘the authorities have turned a blind eye because Chinese society is increasingly focused on the economy’. It means that ‘this is the best time for Chinese poets to flourish’. He repeats variations of this statement in both In Your Face and Breaking New Sky. In the introduction to In Your Face, which predates his Time statement by eight years, he writes that ‘Chinese poetry is no longer a monolith of dogmatism and various isms but one of diversity and vitality’. The latter themes of diversity and vitality are taken up again in Breaking New Sky when he recalls three years after his Time statement that ‘it was only upon editing Otherland magazine in late 1994’ that he grew to see that contemporary Chinese poetry ‘seemed to have taken a turn for the better’. By better, an aesthetic as well as political judgement, he means that ‘poetry, or some of it, was no longer’ written with officialdom in mind but had become ‘an expression of personal poetic truths that readers could identify with’.

Ouyang Yu is not unique among anthologists to assert the diversity of contemporary Chinese poetry. W. N. Herbert observes in his preface to the Jade Ladder anthology that contemporary Chinese poets ‘have embarked on one of the world’s most thorough and exciting experiments in contemporary poetry’ and avows ‘the diversity of mainland Chinese poetry today’ . Yang Lian also hints in his introduction to the Jade Letter anthology at the diversity of contemporary Chinese poetry when he argues that following the deadening impulse of the Cultural Revolution ‘the last thirty years of Chinese poetry has created an era that is one of the most-quick witted and exciting in the whole history of Chinese poetry’.

The question of diversity conceals within it another question which is the question of why diversity receives emphasis in anthologies of contemporary Chinese poetry in English translation. W. N. Herbert recalls in the preface to Jade Ladder that modern Chinese poetry is a product of a two-fold pressure. Firstly, the arrival of modernism through the New Culture or May Fourth Movement of 1919 ‘moved literary writing decisively away from the rules if not the influence of classical forms’. Secondly, the Communist victory in 1949 ‘confirmed and intensified the same tensions between propagandistic “realism” and individual expression that were then afflicting Stalinist Russia’. However, such factors as the death of Mao in 1976, the end of the Cultural Revolution, and China’s opening to the West as well as different movements of poets emerging to explore diverse aesthetic drives have all spearheaded the diversity of contemporary Chinese poetry.

A critical difference between In Your Face and Breaking New Sky is the former’s anarchic introduction compared with the latter’s more normative one. The biographies of poets across In Your Face read more like knowing conversations between friends than the more literary offerings of Breaking New Sky. In de Certeauan terms, the latter is less guerrilla tactics of invasion, or infiltration, and more calculated, or strategic, invitation of reflection. (4) Readers and critics who view the role of anthologies in translation as the polite introduction of another poetry may dismiss Ouyang Yu’s provocatively entitled ‘Poems as Illegal Immigrants: an Introduction’ in his earlier In Your Face as polemical.

However, Ouyang Yu is throwing up a challenge to readers who approach contemporary Chinese poetry as consumption or criticism. His vociferous tone in the introduction to In Your Face is the avant-gardist’s call to arms. He is inviting Australian readers to rethink their relationship to both China and the consumption of poetry. Within the context of the difficulty of writing and getting published in Australia as someone from a non-English speaking background, he writes that ‘translating contemporary Chinese poetry into English for an audience whose main interest in Asia read China is money and everything that goes with it defies description’. The unexpected critical judgement on readers seeking a poetry critical of contemporary China is that if they wish ‘to know what characterizes these poems’ then it is ‘that they are mildly and sensitively anti-Western’.

Despite the milder tone of the Introduction in Breaking New Sky, it recalls the avant-gardist’s call to arms in In Your Face. In what is a ‘labour of love’ for him, Ouyang Yu offers readers, who have now morphed into ‘Australian poetry lovers’, a diverse collection of ‘the most interesting, the most enticing, the most loveable poems’ from ‘the best known and unkown poets, from an ancient shiguo (poetry nation)’. The story of contemporary Chinese poetry is but one step in a long poetic journey which, as Ouyang Yu tells us, the Beijing-based poet, Lin Mang, argues that it can ‘hold its own with the rest of world poetry in that it flies on two wings’. Thus, ‘one wing is its 5000-year-old history of poetry’, and the other is ‘its absorption or assimilation of Western poetry over the last 100 years’. Both mean that it can ‘fly higher’. The invitation is that contemporary Chinese poetry stands on its aesthetic achievements.

Ouyang Yu poses in the introduction to Breaking New Sky the perennial question of what is the lasting quality of a poem and argues ‘it is the unspeakable mysterious truth captured in the brevity of lines that transcends cultures and politics’. In western terms, this is the expressive truth of lyric poetry since the Romantics. Yet Ouyang Yu’s statement reverberates with Yang Lian’s notion in Jade Ladder that the contemporary Chinese poet is ‘a professional questioner, maintaining a constant position of questioning the self and facing up to a constantly changing world’. The power of contemporary Chinese poetry in English translation also lies in what comes across from the Chinese in the very texture of the translation. For Ouyang Yu, direct translation that preserves the original language is the preferred method, operating in his analysis as if the sublime, numbing the senses and ‘adding strangeness to the beauty of the translated poem’ (Breaking New Sky 9-10).

In organising both anthologies alphabetically, and in not limiting himself to one group of interrelated poets or labelling poets according to their aesthetic affiliations, Ouyang Yu allows the diversity of contemporary Chinese poets to flourish within the pages of his anthologies. The question remains that if diversity is one of the characteristics of contemporary Chinese poetry then it is legitimate to ask what kind of China emerges from within the pages of Ouyang Yu’s anthologies, if not any anthology of contemporary Chinese poetry, since poems contain within themselves traces of social life and engagement.

Reading social interactions in China through Ouyang Yu’s anthologies

Ouyang Yu’s 1990s poem ‘Translating Myself’ in his first collection of poetry, Moon Over Melbourne and other Poems, offers a way in to reading the poems across In Your Face and Breaking New Sky as artefacts of social relations. It is suggestive of how the translated poem also conceals within itself the social body of another culture:

I translate myself

from Chinese into English

disappear into appearance of

another existence looking back across

the barrier of tied tongues

at the concealed image of the other body

(83)

Ouyang Yu’s diverse selection of poets in these anthologies allows precisely what is operating across different aesthetic groups to emerge with full and overlapping complexity. The selection of poems puts the diversity of contemporary Chinese poetry under pressure. Diversity implies both aesthetic and representational diversity. Both anthologies engage in a diverse questioning of a shifting contemporary terrain that frequently puts the present in tension with the past. In the 1990s, Michelle Yeh noted that ‘Chinese poetry stands between traditional society, which is fast disappearing, and modern society, which is dominated by mass media and consumerism’ (Anthology of Modern Chinese Poetry xxiii). The poems in In Your Face and Breaking New Sky are not always suggestive of a modern world in tension with a traditional world. Yet as poems in both of Ouyang Yu’s anthologies are drawn from poets across the generations, we see a tension between the present and the past playing out in both anthologies. In In Your Face, such tension is often at the surface of the poem, but in the later anthology, Breaking New Sky, we encounter poems where the losses of the past are more subtly integrated into the concerns of the present. The poetics of individual poets show not aesthetic stagnation but renewal; not naïve reflection but sophisticated engagement.

In Your Face

Featuring seventy poets and with a total of one hundred and eighteen poems, In Your Face gives a wide view of contemporary Chinese poetry with some poets born in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Ouyang Yu argues that the poets born in the 1960s write in a more down-to-earth, or minjian, style, having an eye to ‘ordinary daily details, often sordid ones’ than ‘what they dismiss as the intellectual’ poets of the 1950s ‘whose masters seem all western’. However, those born in the 1970s ‘are even fiercer’ .

Poems like Ah Jian’s ‘Unfortunately, I Do not Have any Belief’ suggest an ennui that functions as cynicism with the status quo. It is highly suggestive of a boredom with politics and a concomitant resignation. The social space conjured in the closing lines of the poem is one in which irony itself has been enfolded into the poem’s indifferent cynicism. We are far removed from any grand statements of purpose or will. The speaker is resigned to the status quo even as he ironises it:

If I am punished eventually for lack of a belief

What can I do

Except bear it (6)

Reminiscent of Ah Jian’s cynicism, Han Dong’s poem ‘A and B’ deals in dissociative relationships in which the sexual tensions of male-female relationships manifest through the speaker’s cynicism. The lyrical in the form of the expressive has been subtracted from the equation of romantic relationships. The poem uses the banal language of official reports that annul any idealistic tendency when the speaker says that ‘for the purpose of a complete description it must be pointed out that / when B stands up after tying the laces, she has semen running down that belongs to A’ (18).

Cynicism also features in Hai Shang’s ‘An Evening Visitor to the House’ that deconstructs literary repression in an ironical, matter-of-fact tone. The poem says of the female lover, or prostitute, that ‘she must have recognised this scene from another century’ (22), but a few lines later ‘she is swaying her buttocks / and walking directly towards the bedroom / and this episode has been removed from the book’ (22). Yet the poem strikes an ideal note in its suggestion of poetry as the refuge of the forbidden. What is excluded in a book can yet find its way into poetry. Contemporary life is a negotiation of psychic freedom.

Domestic life comes under scrutiny in Chen Dachao’s poem, ‘Dreams Shattered Late at Night’, in which the speaker’s sleep is shattered by the intrusion of another’s domestic argument. The poem reaches beyond the confines of its own boundaries to raise the more generalised question of violence within the urban home, suggesting that the urban itself is implicated in the occurrence of such violence:

No-How many homes there must be

in cities today that look sturdy on the

outside

but are broken within (13)

Hou Ma’s ‘Learning English’ critiques the linguistic intrusion of English into social life at the behest of the state. The topic, as articulated in ‘Learning English’, is one which highlights loyalty to one’s own language and hence culture even as the foreign entices one away from one’s own heartland:

As a state policy

English intervened in my life

It had nothing to do with the social environment

In which I lived then and it was useless (25)

…..

I wish that I could fall in love with my lover, the English, one day

Without carrying my wife, the Chinese, in my heart (25)

In Ma Fei’s ‘In the Western Food Restaurant’, the speaker stands apart from those around him, who ridicule an elderly man. The latter’s indifference to etiquette is transferred to the poem itself which critiques imported western lifestyles. The elderly man insists on eating his western food with his chopsticks, saying ‘he was eating, not killing’. In a double move, the speaker’s reaction to the snobbery around him enfolds into the poem an ironic distance to western cultural influence. Ultimately, the poem becomes a commentary on writing poetry:

Unlike my pretentious compatriots

I did not present a face

Of snobbery to the old man

I found him a genuine bloke

Who didn’t give a damn about etiquette

But just did it the way he was comfortable

Like the poem I wanted (46)

Xi Du’s ‘The Son and Daughter Problem’ highlights the emotional cost of the one-child policy not as political critique but as social reality. A married couple fantasises divorce as means to gain a sibling for their unborn child:

We’ll give birth to a lonely generation

Oh, the lonely generation

Even before you are born

you put your parents in despair

Before we wake up from our dreams

we each have divorced the other once (83)

The poems across In Your Face unfold a thought-provoking commentary on contemporary life that challenges any lingering perceptions in Australian readers and beyond of Chinese poetry as rhetoric.

Breaking New Sky

Unlike In Your Face, most of the poets gathered in Breaking New Sky were born in the 1960s and 1970s with a few in the 1980s and with the youngest in 2002. As in In Your Face, they are not necessarily canonised in western anthologies. However, like In Your Face, the poems throughout Breaking New Sky are infused with the existential challenge of day-to-day life, its wryness and its lyricism, albeit in a sensibility that is not always at the vanguard of the poem. The collection features forty-five poets and seventy-two poems.

Bai Helin’s ‘A Fake Rattan Chair’ interrogates the existential quest for a symbol of the past in the form of the chair the speaker’s father once possessed but which now can only be obtained in artificial plastic:

Now the fake rattan chair in a black-coated iron frame

Has retired before its time

Like a weary housekeeper. In it, there is a mess consisting of

An old attaché case, four unwashed items of clothing, three stacks

of trousers

Two mobile phones, a stack of poetry collections and a copy of

The Golden Rose

As well as a white bra, just removed

From my girlfriend’s breasts (16-17)

In Lu Ye’s ‘On the Balcony’, the lyrical interrogation of a symbol of the Chinese historical imaginary in the form of the Yangtze River turns it into a symbol of inner celebration. It performs a complex poetics that shifts the tension between traditional and modern poetic images away from critique to negotiation:

A house from whose balcony one can see the Yangtze

Can be called a luxury residence even at its humblest

My windows all open towards June and the viscera of the

summer exposed

The summer in my body happens to be lush with water grass

Open only for you

There is another Yangtze that originates in my heart, running

through my body

Ah, my heart is the origin of Mount Geladaindong

My veins meandering for 6,300 kilometers, with upper, middle

and lower reaches

And, at its tenderest place

There is also a sandbar in the heart of the river (63)

Zang Di’s ‘The Philosophy Building’ is a complex articulation of meditative inquiry, ironic observation, and unadorned lyricism where the tension between the old and the new is one of nostalgic loss as much as realistic acceptance of the temporal:

built in the 1940s, with a blue-grey roof

like a wing-room directly taken from a temple

its style certainly is not ordinary

beautiful because of dusk and disappearing because of the

punctuation of stars (81)

One of Lu Yu’s other poems, ‘B-Mode Ultrasound Report, Gynecology Department’ ironises both the rhetorical and lyrical modes of language when the speaker writes that “if the report were written in a figurative language” than it would talk about “its shape is cvloser to a torpedo / Than an opening magnolia denundata” (52). This is a sophisticated poetics that conceals within it a tension between woman as vessel and woman as autonomous being:

In a lyrical language, it would have to be written thus:

Ah, this cradle of mankind

Grown on the body of a failed woman

Stops short of germinating despite its rich maternal instinct (53).

In conclusion, in both In Your Face and Breaking New Sky Ouyang Yu gives an expansive picture of what makes contemporary Chinese poetry vibrate. Both collections demonstrate an ongoing renewal of the poetic element in contemporary Chinese poetry and offer a window into the complexities of contemporary social life.

Notes

1 This essay with slight alterations was presented as a paper at the Association for the Study of Australian Literature Conference ‘Looking In: Looking Out: China and Australia’, which was held in Melbourne, 11-14 July 2017, and draws on my review of Breaking New Sky in TEXT. http://www.textjournal.com.au/april14/giannoukos_rev.htm

2. See my review of I Too Am Salammbo in Rochford Street Review.

3. See my review of Breaking New Sky in TEXT. http://www.textjournal.com.au/april14/giannoukos_rev.htm

4. In The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau identifies tactics with the disempowered and the strategic with the empowered.

Works Cited

Bruno, Cosima. ‘The Public Life of Contemporary Chinese Poetry in English Translation.’ Target: International Journal of Translation Studies, vol. 24, no. 2, 2012, pp. 253-285.

De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Randall, U of California P, 1984.

Herbert, W. N., et al. Jade ladder: Contemporary Chinese Poetry. Bloodaxe Books, 2012.

Jose, Nicholas. ‘Australian Literature Inside and Out.’ (Special Issue: ‘Australian Literature in a Global World.’ Eds. Wenche Ommundsen and Tony Simoes da Silva). Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, 2009.

Ming, Di, editor. New Cathay: Contemporary Chinese Poetry. Tupelo Press, 2013.

Ouyang, Yu. Breaking New Sky: Contemporary Poetry from China. Introduced and translated by Ouyang Yu, Five Islands Press, 2013.

‘In Your Face. Contemporary Chinese Poetry in English Translation.’ Introduced and translated Ouyang Yu, Otherland Literary Jornal, no. 8, 2002.

‘Motherland, Otherland: Small Issues.’ Antipodes, vol. 18, no. 1, 2004, 50-55.

‘Translating Myself.’ Moon Over Melbourne. Papyrus Publishing, 1995.

Yeh, Michelle. Anthology of Modern Chinese Poetry. Yale UP, 1992.

TINA GIANNOUKOS is a poet, writer, reviewer, and researcher. Her latest collection of poetry, Bull Days (Arcadia, 2016), was shortlisted in the 2017 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards and longlisted for the 2017 Australian Literature Society (ALS) Gold Medal. She has a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Melbourne where she has taught in Creative Writing. She has lived and worked in Beijing.

The Stolen Bicycle

The Stolen Bicycle Lunar Inheritance

Lunar Inheritance NICHOLAS JOSE has published seven novels, including Paper Nautilus (1987), The Red Thread (2000) and Original Face (2005), three collections of short stories, Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (a memoir), and essays, mostly on Australian and Asian culture. He was Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy Beijing, 1987-90 and Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, 2009-10. He is Professor of English and Creative Writing at The University of Adelaide, where he is a member of the J M Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice.

NICHOLAS JOSE has published seven novels, including Paper Nautilus (1987), The Red Thread (2000) and Original Face (2005), three collections of short stories, Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (a memoir), and essays, mostly on Australian and Asian culture. He was Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy Beijing, 1987-90 and Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, 2009-10. He is Professor of English and Creative Writing at The University of Adelaide, where he is a member of the J M Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice. Middle of the Night

Middle of the Night Xia Fang, born in 1986, is a bilingual poet and translator. She has published two collections of translated poems and her own poetry has appeared in

Xia Fang, born in 1986, is a bilingual poet and translator. She has published two collections of translated poems and her own poetry has appeared in  Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu

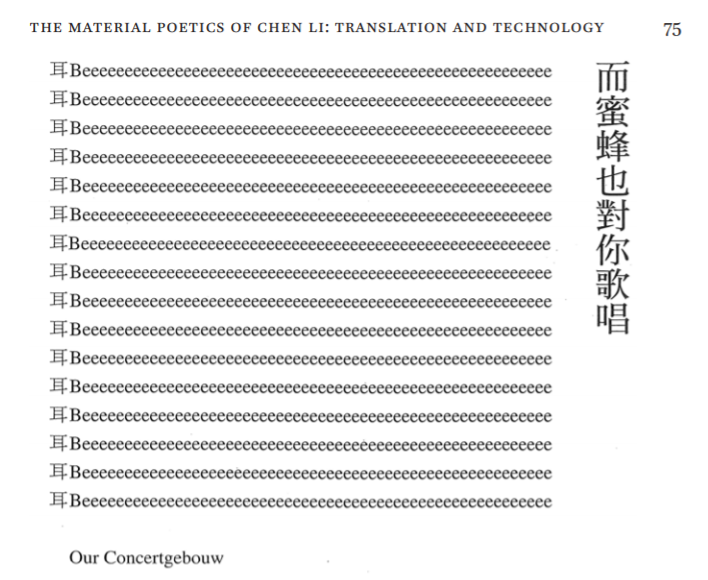

Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Xiaoshuai Gou was born and raised in China. He has been working as a teacher of English and Mandarin as a second language and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of South Australia.

Xiaoshuai Gou was born and raised in China. He has been working as a teacher of English and Mandarin as a second language and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of South Australia. Sanaz Fotouhi is currently the director of Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. Born in Iran, she grew up across Asia and holds a PhD in English literature from the University of New South Wales. Her book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution was published in 2015 (I.B. Tauris). Her stories and creative fiction are a reflective of her multicultural background. Her work has appeared in anthologies in Australia and Hong Kong, including Southerly, The Griffith Review, as well as in the Guardian UK and the Jakarta Post. Sanaz is one of the founding members of the Persian Film Festival in Australia as well as the co-producer of the multi-award winning documentary film, Love Marriage in Kabul.

Sanaz Fotouhi is currently the director of Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. Born in Iran, she grew up across Asia and holds a PhD in English literature from the University of New South Wales. Her book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution was published in 2015 (I.B. Tauris). Her stories and creative fiction are a reflective of her multicultural background. Her work has appeared in anthologies in Australia and Hong Kong, including Southerly, The Griffith Review, as well as in the Guardian UK and the Jakarta Post. Sanaz is one of the founding members of the Persian Film Festival in Australia as well as the co-producer of the multi-award winning documentary film, Love Marriage in Kabul.