Martin Edmond reviews “Moving Among Strangers” by Gabrielle Carey

Moving Among Strangers: Randolph Stow & My Family

Moving Among Strangers: Randolph Stow & My Family

by Gabrielle Carey

ISBN 978 0 7022 4992 1

Reviewed by MARTIN EDMOND

The quest memoir, poorly defined as a genre, is an ancient form with roots, most likely, in pre-literate times. Briefly, it is a narrative, told usually in the first person, of the progress of a quest. The protagonist sets out to find something or someone and, after the search is over, tells an audience what happened along the way. A peculiarity of the form is that failure often figures as a peril of the quest and, paradoxically, part of its successful outcome. This sounds more enigmatic than it is: a gatherer who sets out in search of yams and comes back with bush tomatoes has both failed and succeeded; so has a hunter who goes after kangaroo and comes back with nothing at all: each will still have a story to tell. The success/failure axis of the quest, and the uncertainty it presupposes, is one of the driving forces of narrative in this form of non-fiction; and the multiple outcomes it proposes make, often enough, for literature that is both flexible and engaging; sometimes very moving too.

Thus, the protagonist of a quest memoir does not necessarily find what s/he is looking for; but might find something else. The form is adaptable and capacious and requires of its reader absolute trust in the narrative voice. There is no place here, and no point to, the unreliable narrator. Self examination, however, is very much of the essence and in this respect quest memoir has strong affinities with memoir in its standard form; but has a different relation to time than either the standard memoir or its near cousin, autobiography. Although it can take the form of a chronological account, it does not need to and frequently does not. In sophisticated hands a quest memoir may more resemble a work of fiction; you may not ever know quite what is coming next and its time chart might look more like a mosaic or a collage than a progression.

Gabrielle Carey’s Moving Among Strangers is a quest memoir with just such a complex, mosaic, time structure. It is also a quest that in some respects fails to achieve its objective; but in that failure discovers other things. She tells her story with grace, delicacy and precision. And with a kind of circumspection that is, to use a by now almost obsolete word, mannerly. This quality, this reticence, is not simply characteristic of the writing in Moving Among Strangers, it is one of the themes of the book; and, inter alia, a virtue possessed by its principal subject, the writer Randolph Stow. Carey writes several times of the old virtues, of which reticence is one; others include simple good manners, respect for the privacy of others, quiet observation without the need to proclaim the results of that observation; and the ability to withhold judgment, not just for a year and a day but over the course of an entire lifetime. As the quest memoir might fail and yet thereby attain paradoxical success, these old virtues may be seen as a set of negatives which, to use a photographic metaphor, when properly developed show up as incontrovertible positives.

Gabrielle Carey has, as we say, always known there was some kind of family connection between her mother’s people and the Stows but has never investigated it fully—until now. The book opens with her mother beginning to die of cancer, a process that will take three weeks. A week into that brief period of exit, Carey brings her mother an anthology of Randolph Stow’s writing and is astonished when she, who has apparently ceased to be able to read, delivers a near perfect recitation of her favourite Stowe poem called, appropriately enough, ‘For One Dying’: Now, in that place where all birds cease to sing . . . Carey tries to persuade her mother to write to her old friend, then living in England, but she will not. In the end, the author writes herself and so initiates a brief correspondence which initiates the quest that animates the rest of the book: that is, a search for the hidden connections between her mother, Jean Carey, neé Ferguson, and her rather younger confrère, Randolph ‘Mick’ Stow.

It is not my intention to detail the stages of this quest, which is various and strange and leads the author far afield—to Western Australia, where she meets or re-meets multiple among her lost and/or forgotten relatives, from both sides of her family; and to England where, under an oak sapling in Wrabness Wood outside the village of Harwich in Suffolk, she visits Randolph Stow’s grave. For by this time, before they have had a chance to meet or even to talk upon the telephone, he too has died: one of the most poignant missed connections in this quest is a result of Carey’s failure to notice the telephone number written at the bottom of the page of one of Stow’s letters to her until it is too late to call. When she returns from the furthest of these pilgrimages, there is another death, the third, this time that of her older sister, with whom she has, somewhat fractiously, nursed their dying mother in the earliest stages of the book.

In some respects, then, the book cannot help but become a meditation upon dying. And, concomitantly, a meditation upon what is lost to us with the death of those who are close to us, whom we have known or loved, admired or respected. Carey’s accomplishment here is two-fold: while on the one hand she expertly notes the gaps in memory that can never be filled, the personal information that was stored only in someone’s mind, and then imperfectly, the documentary traces that were too insignificant or too troubling to be preserved; on the other she uncovers a rich cast of living characters who by their palpable presence on the page, bring back much that seemed irretrievable and add more that was not known before. I refer here not only to the rediscovered extended family in WA but also to Stow’s friends in Suffolk who do so much to fill out his portrait.

That portrait is, for me, the central achievement of this book. Again, it is deft and economical, elegant and intricate: accomplished as much by omission as by inclusion. There’s a kind of tact involved here which is supremely important in this kind of writing: you are going to have to speculate but, by the same token, there are few things more tiresome than an author who speculates too much. Those texts infected with might-have-beens and would-have-beens, perhapses and of courses, only serve to erode the reader’s trust in the authorial voice. Here we have something almost opposite: it is Carey’s refusal to speculate that somehow allows Stow, that silent man, a voice. Here, again, it’s the negatives that develop a positive that is far more convincing than any speculative portrait might have been.

Her refusal to speculate also allows Stow to preserve his privacy, which was evidently of great importance to him as a man and as an author; he remains an enigma to the end. There were just eight novels, five of them written before their author turned forty; a handful of poems, again mostly written in the first half of his working life; a few other heterogeneous works, including libretti and children’s books. The latter part of his life, which was spent in England, living quietly in that part of the country from which his English ancestors came, produced just three books: the twinned Visitants and The Girl Green as Elderflower; and the last book, called The Suburbs of Hell, published in 1984. For the next quarter century, until his death in 2010, Stow published nothing.

Silence in a writer is provocative: witness the swirl of conjecture that still surrounds the author of The Catcher in the Rye. More recently, in the plethora of books that have come out to mark the centenary of the birth of William Burroughs, we have his own startling testimony: that he believed an evil spirit entered him at the time in the 1940s when he shot his wife dead; and that his literary career was a sustained attempt, ultimately successful, to exorcise this demon. Stow is a very different writer from Burroughs but it does seem that in his case, too, there was a need for the kind of exorcism that writing can accomplish; and when he had said what was in him to say, or what his daemon required of him, he was content simply to live. His conflicted relationship with his home country was certainly one of the engines of his writing and it is quite possible that it was only by leaving all that behind that he could attain a modicum of happiness in his personal life. Carey’s evocation of Stow’s last years, courtesy of his English friends, is exquisitely modulated and very moving, intimate even as it leaves Stow’s essential privacy intact.

Gabrielle Carey’s Moving Among Strangers is a relatively short book, beautifully designed and presented by the University of Queensland Press, in which the strangers of the title turn imperceptibly into friends or, at the very least, acquaintances; a quest which does not achieve its aim and yet somehow manages to illuminate its subject in such a way that we as readers feel, howsoever briefly, that the unknown may yet be known; an evocative, highly descriptive, journey to places as far apart as the dusty coasts of south western Australia are from the green shade of a Suffolk village; most of all, a foray to the edges of that undiscovered borne from which no traveller returns.

Near the end of the book is a section which is rather like the old rhyme ‘The House That Jack Built’, summarising the path of incident and co-incidence that made up her quest. Then, in a lovely paragraph that begins: This, then, is what I have learned about the dead . . . she writes her conclusion. There is a profound sense here that it is in conversation with the dead we most become ourselves: something that pre-literate peoples have always believed. I kept thinking of the words of a Warren Zevon song, from his late album, Life’ll Kill Ya, itself a kind of quest memoir, and written within sight of his own early death. The refrain suggests: we take that holy ride ourselves to know. It is a holy ride that Carey takes and, on the evidence of the book’s ending, increased self-knowledge was a consequence; as well as an understanding of the beguiling phenomenon of the effervescence of elderflower wine. For readers there is something more: an insight into the mystery at the heart of a writer’s vocation.

MARTIN EDMOND is an author, poet, screenwriter who teaches at UWS. His awards include the Jessie Mackay Award and the Montana Book Award. He lives in Sydney.

Joel Ephraims lives on the South-East Coast of NSW. He studies creative writing, philosophy, and literature at the University of Wollongong. In 2011 he won the Overland Judith Wright Poetry Prize and in 2013 his chapbook of poetry, Through The Forest was published as part of Australian Poetry and Express Media’s New Voices Series.

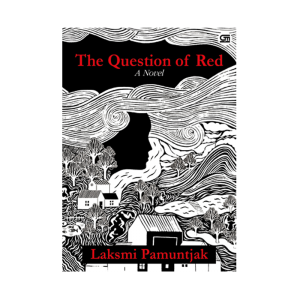

Joel Ephraims lives on the South-East Coast of NSW. He studies creative writing, philosophy, and literature at the University of Wollongong. In 2011 he won the Overland Judith Wright Poetry Prize and in 2013 his chapbook of poetry, Through The Forest was published as part of Australian Poetry and Express Media’s New Voices Series.  The Question of Red

The Question of Red

Autumn Royal is a poet and PhD candidate at Deakin University. Autumn’s writing has appeared in publications such as Antipodes, Cordite, Rabbit, and Verity La.

Autumn Royal is a poet and PhD candidate at Deakin University. Autumn’s writing has appeared in publications such as Antipodes, Cordite, Rabbit, and Verity La. Saba Vasefi is a poet, a documentary filmmaker and human rights activist. She was a lecturer in Tehran, Shahid Beheshti University. She became a member of the Committee of Human Rights Reporters. She also worked as a reporter for the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. She was twice a judge for the Sedigheh Dolatabadi Book Prize for best literature on women’s issues. She was expelled from the University after 4 years of teaching due to her activism. Her documentary film about child execution in Iran ”Don’t Bury My Heart” has been screened for the BBC, United Nation, Amnesty International, The Copenhagen International Film Festival, SOAS university, University of Oslo, Dendy Opera Quays cinema and Seen & Heard Film Festival. She has published poems, research papers, articles, reports, interviews and multimedia about executions, censorship, and women and children’s rights. Her multimedia piece, “Shirin, A Soloist in the Silence Room” was screened in Geneva for the UN. She has also had work published in the anthology “Confronting the Clash: The Suppressed Voices of Iran. She was director of First Sydney International Women’s Poetry Festival (Woman Scream). Currently; she is completing a postgraduate degree in documentary at The Australian Film TV and Radio School (AFTRS).

Saba Vasefi is a poet, a documentary filmmaker and human rights activist. She was a lecturer in Tehran, Shahid Beheshti University. She became a member of the Committee of Human Rights Reporters. She also worked as a reporter for the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. She was twice a judge for the Sedigheh Dolatabadi Book Prize for best literature on women’s issues. She was expelled from the University after 4 years of teaching due to her activism. Her documentary film about child execution in Iran ”Don’t Bury My Heart” has been screened for the BBC, United Nation, Amnesty International, The Copenhagen International Film Festival, SOAS university, University of Oslo, Dendy Opera Quays cinema and Seen & Heard Film Festival. She has published poems, research papers, articles, reports, interviews and multimedia about executions, censorship, and women and children’s rights. Her multimedia piece, “Shirin, A Soloist in the Silence Room” was screened in Geneva for the UN. She has also had work published in the anthology “Confronting the Clash: The Suppressed Voices of Iran. She was director of First Sydney International Women’s Poetry Festival (Woman Scream). Currently; she is completing a postgraduate degree in documentary at The Australian Film TV and Radio School (AFTRS). Deb Matthews-Zott has published two collections of poetry, Shadow Selves (2003) and Slow Notes (2008). She runs the Australian Poets’ Exchange Facebook Group, which has a membership of over 800, and is convener of SPIN (Southern Poets and Musicians Interactive Network). ‘The Weir’ and ‘The Pug Hole’ are from her verse novel in progress, ‘An Adelaide Boy’.By day she is a Librarian.

Deb Matthews-Zott has published two collections of poetry, Shadow Selves (2003) and Slow Notes (2008). She runs the Australian Poets’ Exchange Facebook Group, which has a membership of over 800, and is convener of SPIN (Southern Poets and Musicians Interactive Network). ‘The Weir’ and ‘The Pug Hole’ are from her verse novel in progress, ‘An Adelaide Boy’.By day she is a Librarian. sean burn’s third and latest full volume of poetry is that a bruise or a tattoo? (isbn 9781848612945)

sean burn’s third and latest full volume of poetry is that a bruise or a tattoo? (isbn 9781848612945)