Paul Giffard-Foret reviews “My Van Gogh” by Chandani Lokuge

My Van Gogh

My Van Gogh

By Chandani Lokugé

Arden (2019)

ISBN 978-1-925984-17-0

by Paul Giffard-Foret

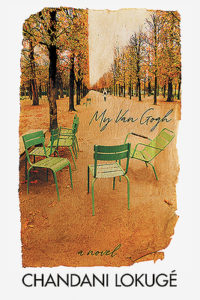

Chandani Lokugé’s fifth novel My Van Gogh takes the reader on a romantic and artistic journey across borders, from the rural farming lands of Victoria in Australia, where part of her characters’ family on their father’s side is from, to some of France’s touristic hotspots, including scenic areas of Le Loire Valley, the southeast region of Provence, or its capital city Paris. The metropolitan provenance of the novel is made evident by the design of the book cover. It shows a snapshot of what is reminiscent of the Tuileries Garden, which is located in the vicinity of Le Louvre Museum. This is despite the fact that Lokugé actually writes from the periphery of what constitutes her Sri Lankan Australian background. The terms of “periphery” and “metropolitan” are used here with a postcolonial agenda in mind, to refer to the ways in which the old structures of Empire and European colonialism still play out in our contemporary era. Lokugé is aware of such lingering structures insofar as her oeuvre as a novelist may easily fall under the loose category of “postcolonial fiction”. As an illustration, Lokugé’s second novel Turtle Nest, published in 2003, dealt with the issue of sex tourism and trafficking of local children for Western customers in a small fishing village in Sri Lanka.

We may wonder, then, what postcolonial elements there are in a novel in which the main characters are white and relatively privileged —symbolically at least, being endowed with cultural capital—and where a driving theme is the artistic legacy left by one of the most iconic Western painters and representatives of High Culture, namely Van Gogh? To revert to my earlier allusion to Turtle Nest, this novel shares with My Van Gogh a common concern with travel (and tourism) that itself recurs as a distinct motif in diasporic literatures of dispersal by migrant authors. Yet this time, the gaze happens to be reversed, for My Van Gogh, as its title suggests, does not so much speak of the master painter’s life as it heralds its appropriation by the margins. My Van Gogh’s central Australian-born character, Shannon, sets out on a quest for meaning by travelling to France in very much the same way that the West would journey to the Orient and the Far East in the hope of being “revealed” by the sheer Sublime of the place, by its spirituality, its history, art and craft. The tourist’s gaze operates a process of “museumification” which not only sublimates the real, as Jennifer Straus spelled out during her speech at Lokugé’s book launch, but it also flattens things out by silencing “accidents” of history.

So it is to Lokugé’s credit that the rippling echoes of those series of murderous terrorist attacks which have struck France since 2015 can be felt. These attacks carry along their trail of death haunting memories of a colonial era thought to have been long gone, since the last major terrorist attacks on French soil took place in the context of Algeria’s War of Independence and Algeria’s Civil War in the 1990s. The blight of terror is another common point with Lokugé’s homeland, Sri Lanka. As Shannon and Guy are walking along the promenade in Nice on Bastille Day, they must bear witness to “a ceremony to commemorate the lives lost” (55) on that very same spot and day in 2016, killing eighty-three. Shannon’s prolonged sojourn in France is meant as a way for him to reconnect with his French mother and brother Guy, both of whom are “exiled” in France away from the family farm in Australia, as well as with his great-grandfather Grand Pierre, who fought and died a hero during the Great War of 1914-1918. Yet their mother remains an “absent presence” throughout the novel, having cut off links with her family, while Guy, being now well established in his adopted country, and having started a new life in Paris as an art dealer, feels in some way estranged from Shannon. Grand Pierre’s military heroism, which is very much part of the family’s lore, gets somewhat dampened and overshadowed by the fact that his body remains are yet to be exhumed and identified after all these years.

Their scattering evokes the scattering, more broadly, of family relationships, friends and lovers, and in the final instance, of identity markers themselves, which is an aspect of our postmodern “liquid” selves that transpires in Lokugé’s novel. Put simply, identity relates to people and places, but the latter in My Van Gogh remain loosely connected and grounded. Lokugé highlights her characters’ difficulties to communicate with, and feel for, one another. Her characters, indeed, seem enveloped within a Hopperesque halo of solitude, like a carapace preventing them from facing and sharing with others those vagaries of life that otherwise fill the void of our existence. In this light, Lokugé’s choice of a happy ending sounds like a trompe l’oeil, especially with respect to the book cover. It shows empty chairs lying stranded and looking abandoned, and an individual’s silhouette walking away into the distance towards a vanishing point, being flanked on both sides by rows of tall, erect, autumnal trees. This image intimates that one’s personal journey is a lonely trail, as it must have been for the tormented, maddened Van Gogh.

In effect, the many touristic sites and scenic places (including Van Gogh’s temporary home in Arles), as well as churches and museums, though they are in part aimed at recalling her mother’s presence, all seem but a poor distraction and lack substance in the face of Shannon’s own pill-dependent depressive state. We are told that “for Shannon, also, it had become ordinary, a boring show staged for self-indulgent tourists. That quiet desperation, that unconscious despair that is concealed under the amusements of mankind, Shannon reflected, recalling the words of Thoreau.” (54) I am here reminded of award-winning French author Michel Houellebecq’s dystopian portrayal of France as a theme park for foreign visitors and local tourists in his novel, The Map and the Territory, whereby largely uninhabited town centres have been transformed into standardised temples of consumption and sanitised variations of the picturesque. As a review of the novel published in the New York Times concurred, “Houellebecq’s Paris exists in a state of flagrant social breakdown and the countryside has become an emptied theme park of itself.”

The parallel with Lokugé’s work can be further made here, since both authors have shown a deep, continuous interest in tourism as a powerful metaphor for our globalised era. As the New York Times review added, The Map and the Territory “deals with art and architecture, rather than sex tourism. It is set in galleries and villages rather than S-M clubs and massage parlors.” My Van Gogh similarly deals with the art market as a global form of currency. As earlier mentioned, Guy is a gallerist, and Shannon a student in art history. Shannon’s girlfriend Lilou, besides being a tour guide, is a musician and a painter herself, while Guy’s French lover Julie graduated in Fine Arts. Furthermore, the novel is peopled by references to mythical figures such as Proust, Beckett, Hemingway or Matisse, who at some point lived and worked in France, at a time—at least until World War Two— when Paris happened to be the world’s artistic hub and would attract artists from different nationalities, including Van Gogh himself. So at some point in the novel, Shannon for example goes to visit the southeastern village of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where Van Gogh was interned in an asylum for a year there, and where he achieved some of his most famous paintings.

In the same way that Houellebecq is, Lokugé is further concerned in her novel with those children belonging to the post-soixantehuitard (sixty-eight) generation, as they are dubbed in France, who grew up in the wake of the May 1968 Revolution. The upheaval, mostly student-led, entailed among other things a radical dismantling of the traditional family. Lilou, whom Shannon met during his meanderings across France, for instance is said to have parents who lived “wayward, hashish-filled lives—with a tribe somewhere in the Himalayas from what she’d seen in Facebook months ago.” (120) As Shannon tells her: “We are a lost generation—une génération perdue.” (121) This historical allusion to the devastation wrought by the Great War upon the youth in particular points to the existence of a crisis of a spiritual, metaphysical and civilisational nature at the heart of Western, and more specifically, French contemporary society, as Houellebecq himself exposed in The Map and the Territory, which won the Prix Goncourt (the equivalent of the Booker Prize) in 2010. This crisis would ripen to a full and explode in the form of the Yellow Vest protests by the end of 2018. The occupation of roundabouts by Yellow Vests across the French territory, in particular in deserted rural areas where the movement started, represented a desire to rebuild solidarity and cohesion in the face of a torn social fabric, as well as gain democratic sovereignty through this modern version of the Greek agora. Lokugé in her novel summons the imagery of the carrefour (not the hypermarket chain here, but its semantic meaning of a “crossroad” in French) to poetically express the random contingency and situatedness of cross-cultural love, which, as the reader is led to understand, can be undone as quickly as it can be struck. And this is precisely within the knots of this tension that lies the beauty and dramatic force of Lokugé’s prose. To quote from the novel:

Carrefour…

They lay entangled in each other. Her hand in his, a drowsy bird. The room was almost black, a shadow of light across the bed. He could faintly see her face raised beside his. They hardly knew one another. That was beautiful, he said. Thank you, she whispered. It’s a gift then. Whose voice, whose words? Didn’t matter. They were etched in him, deep inside. He kissed the fold of her elbow. Carrefour—he said—meeting place. He felt the texture—this word so foreign to him. Meeting place, she said, lieu de rencontre. (57)

A carrefour implies a certain level of reciprocity and a readiness to let go of one’s own cultural attributes to meet the Other on neutral, naked grounds. Travel narratives usually make for good romance precisely so because the characters in these narratives stand outside of their comfort zones. Standing outside or in-between cultures as do Guy the expatriate and Shannon the traveller make both brothers more easily vulnerable or susceptible to the possibility of yielding to the unknown of cross-cultural romance. As the French Iranian author, Abnousse Shalmani, reminds us, Guy and Shannon are “métèques” (a word originating from Greek and meaning whoever resides away from home). As such, métèques “do not have buried secrets within the attics of country cottages, no class prejudices, no embarrassment vis-à-vis History, culture, language; he or she has in effect left of this behind. The métèque goes beyond rules, common decency, social order.” (Shalmani 106; my own translation) France’s geography, located at the crossroads between six nations (which is why it is known as the hexagon), spans cultural realities as distinct as Provence’s Mediterranean Sea and the wine routes and forests of Alsace in the east. Alsace is probably the most métèque of all regions considering its historical ties in Germany, where Guy and Shannon’s great-grandfather Grand Pierre was killed. As a former imperial power and neo-colonial player, France has often proved unceremoniously unkind and unwelcoming to its métèques. Notwithstanding, My Van Gogh with its wanderings across some of France’s over-saturated historic sites operates a cosmopolitan itinerary worth following for the reader insofar as this scenic drift becomes a pretext for an inward exploration of the human condition itself.

Works Cited

Shalmani, Abnousse. Éloge du Métèque. Grasset, 2019.

Shulevitz, Judith. “Michel Houellebecq’s Version of the American Thriller.” New York Times, Jan. 13, 2012. <https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/15/books/review/michel-houellebecqs-version-of-the-american-thriller.html> (Accessed 19 Dec. 2019)

———————

PAUL GIFFARD-FORET completed his Ph.D. on Australian women writers from Southeast Asia at Monash University’s Postcolonial Writing Centre in Melbourne, having completed his MA in Perth on Simone Lazaroo’s fiction. Paul’s research deals with gender studies, racial and cultural hybridity, migration, multiculturalism and related issues with a focus on postcolonial and diasporic Anglophone literatures from Australia, Southeast Asia and India. His academic work has appeared in various journals and magazines in the form of peer-reviewed articles and literary reviews.