Martin Edmond reviews “Can You Tolerate This?” by Ashleigh Young

Can You Tolerate This

Can You Tolerate This

by Ashleigh Young

ISBN : 9781925336443

Reviewed by MARTIN EDMOND

Can You Tolerate This? is a collection of twenty-one personal essays on a variety of seemingly disparate subjects; some just a few hundred words long; others more than thirty pages. All are highly accomplished, both stylistically and in terms of the use they make of their author’s existential, experiential and other concerns. They are also, in way that is subtle to the point of subversion, very amusing; but it is a painful kind of humour, reminiscent of the paroxysm of pain we may feel when we bang our elbow on some hard surface like a wall or a door or the arm of a chair, and activate our funny-bone.

Bones are in fact where the collection begins, with a short account of the life of an American boy who suffered from a rare disease which caused another skeleton slowly to grow around his original one. This introduces a major theme of the collection, its examination of the complexity of the mind-body relationship, using a variety of curious examples from the world but mainly employing the author herself, her defaults and her daily activities, the various milieu in which she moves, as a subject for speculation—often of a rather fraught kind; but therein, as I said, lies the humour.

So this is the first point to make: although the book may seem to be a collection of disparate pieces, it is in fact a highly wrought artefact, as unified as any good novel or memoir may be; in fact, better unified than most. One of these unifying factors is the body / soul dynamic, mentioned above, wherein the author inquires into her own condition, or habits, in such as a way as to try, not so much to explain them, as to escape from some of their more oppressive effects. Here, through a curious alchemy, the compassion which she shows to others, like her dying chiropractor (in the title piece) is somehow, perhaps by means of the excellence of her style, extended to herself—and by analogy to her readers, who will recognise in the author’s predicaments the ghosts of their own.

This kind of ‘therapeutic’ writing can, in less assured hands, come across as awkward, self-serving or even self-pitying; but not in this case. Ashleigh Young’s voice is bracing and illuminating; although she is often tentative, sometimes almost to the point of hyper-sensitivity, she is always honest; and these are the qualities—honesty, illumination, vigour, sensitivity—that make the collection so beguiling. Whether she is practicing yoga, going for a bike ride, adjusting her breathing to the demands of cycling or running, as a reader you experience a feeling of rare empathy with the authorial voice.

So her self-portrait, or rather her succession of self-portraits, is entirely successful. In part this is because of another, and deeper, unifying aspect to the collection: deftly, without ever really seeming to try, almost by stealth, Can You Tolerate This? is also a portrait of the author’s family and, as a consequence, an account of her growing up in the small town of Te Kuiti in New Zealand’s North Island, with some holiday sojourns at Oamaru in the South. As the book proceeds, especially through its longer essays, we come to know her family—her father and mother, her two older brothers, herself, various family pets—almost as well as we may know our own. This splendid family portrait is achieved without recourse to whimsy, cuteness, or special pleading; most of what we see is far too raw, and too real, for that. In some respects this is the most remarkable aspect of a very remarkable book.

The long essay, ‘Big Red’, for example, is almost unbearably tense to read because of the sense of risk expressed in its account of the erratic career of Ashleigh’s much-loved older brother JP (who calls her ‘Eyelash’); that something untoward might happen to him, though in fact nothing does, gives the essay the character of a thriller. Moreover, and this is an example of how highly wrought this collection is, that feeling of incipient dread does pay off, much later in the book, in the catastrophe which afflicts the other, the elder brother, Neil, by now living in London. I won’t, of course, say what that is.

The father, with his benign eccentricities, his obsession with flight, his odd remarks; the mother, too, in her attempts, for example, to banish from mirrors the reflections of all those who have ever looked into them, become as vivid as the two brothers. The account of the mother’s writing life, which, in the piece called ‘Lark’, concludes the collection, accomplishes something almost unprecedented: a merging of voices, in which we become unsure if we are reading the mother’s writing or the daughter’s redaction of it. This is, apart from being a stylistic tour de force, an example of familial love raised to a higher power—and brings the book to a winning, if poignant, close.

Like its thematics, the book’s writing proceeds by indirection. Young’s prose style seems relatively straightforward, unornamented or only lightly ornamented; yet her sinuous, seductive sentences take us, almost inadvertently, into very strange places indeed. Witness, for example, her digression upon women’s body hair (‘Wolf Man’, p. 138) which begins: My moustache was negligible in comparison to the hair on the faces of these women and ends The discomfort grows from within, as if it had its own dermis, epidermis, follicles. This is because she is, as a writer, incapable of dishonesty—neither the larger sort which invents in order to cover up, or divert attention from, uncomfortable things; nor the smaller kind which prefers something well said to something, perhaps painfully, or hilariously, true.

This is a brave, sometimes confronting, always intriguing, often compelling, and distinctly unusual book. The essays are consistently entertaining in a way that is rare in literary non-fiction of any kind. The voice is one which readers will fall in love with; they will actively wish for the author to succeed in her life’s endeavours; while recognising that success may be an impossible goal; or, at the very least, a goal impossible to measure. They will feel the same way about the wonderfully eccentric, though entirely typical, Young family, right down to the miniature dachshund with the back problem.

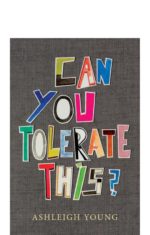

A warning for Australian readers: Ashleigh Young is a New Zealander and her book, republished by Giramondo in the Southern Latitudes series, with a stunning cover by Jon Campbell, originally came out in 2016 from Victoria University Press in Wellington. Ashleigh Young won, along with Yankunytjatjara / Kokatha poet Ali Cobby Eckermann, also a Giramondo author, one of eight coveted Yale University’s Windham-Campbell Prizes, worth $US165,000, awarded in 2017. But that may not be enough to banish the instinctive, almost visceral, disregard most Australian readers have for works from across the Tasman; as if nothing that comes from there could ever rival the terror and the grandeur the best Australian writers are able to command. Nor the inadvertence and obtuseness of the worst.

I don’t quite know what to say about this ingrained prejudice. As a New Zealander myself, albeit one who has lived nearly forty years in Australia, I have never yet been able to compose (it is not for the want of trying) the aphorism that would encapsulate, and so detonate, this unwillingness to engage with a close neighbour. I think that the domestic economy in Aotearoa may be so fundamentally different from the one here that Australians cannot go there. I mean it is so tender and so violent, so intimate and so alienated, so intricately genealogical, that to do so would risk a vastation.

Ultimately, perhaps the problem is the accommodation, however imperfect, between indigenes and settlers that Aotearoans have embarked upon, which remains as yet unattempted here. This of course opens up another interpretation of Ashleigh Young’s title; as if it might be addressed to all the nay-sayers among us who might instinctively resile from a book that comes from so far away, and yet so near at hand, as Te Kuiti. But it also augments the original meaning: some kind of fundamental readjustment of skeletal, no less than existential, or even spiritual, structures might result. It might even be the intention. Can you tolerate this? You could try.

MARTIN EDMOND was born in Ohakune, New Zealand and has lived in Sydney since 1981. He is the author of a number of works of non-fiction including, Dark Night : Walking with McCahon (2011). His dual biography Battarbee & Namatjira was published in October 2014.