“Light Borrowers: UTS Writers’ Anthology 2018” reviewed by Beejay Silcox

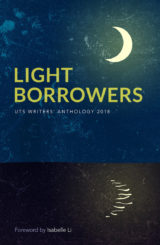

Light Borrowers: UTS Writers’ Anthology 2018

Light Borrowers: UTS Writers’ Anthology 2018

Foreword by Isabelle Li

ISBN: 9781925589627

Review by BEEJAY SILCOX

“In the beginning, it was just us and the words,” writes University of Technology Sydney (UTS) student –and writer – EM Tasker. “We sang them into being, and they existed only in our minds. They reproduced by passing from the lips of one person to the ears of another. But that meant they could only reproduce when people gathered. That was until Writing joined the relationship. The resulting ménage à trois was wildly successful.” (171)

For 32 years, UTS has been celebrating the fruits of that lexical love triangle by publishing an anthology of work penned by its Creative Writing students. This year’s lovingly-assembled edition, Light Borrowers, borrows its title from Sylvia Plath’s poem ‘The Rival’, and with it the tension ever-present in Plath’s poetry – the glorious tension between beauty and annihilation.

As a reader, opening an anthology is akin to entering a room of strangers; we arrive hopeful but nervous, ears pricked for conversation, camaraderie and conflict. How (and how well) we are welcomed is largely dependent on our hosts, on how well we are introduced to the crowd. In Light Borrowers, UTS alumna, author and translator Isabelle Li greets us warmly at the door with the key to a live and lively room. There is one line, she argues in her foreword, that will unlock the anthology; it is waiting for us near its midpoint, in a poem by Shoshana Gottlieb: “The In Between / pockets of time that happen as we wait for / the moments we beg to define us.” (163)

Light Borrowers is anchored in this ‘In Between’. Across a range of genres, from memoir to flash (one of its most memorable contributions by Qing Ming Je is a single, knife-edged sentence), each of its 28 pieces inhabit the liminal spaces that separate, connect and define us. Between childhood and adulthood; believing and knowing; memory and forgetting; remembered pasts and imagined futures; fable and fact. Between, as Gottlieb describes, “the Things We Do and the Things That Happen To Us.” (164)

In Sydney Khoo’s ‘I’m (Not) Lovin’ It’ we slip between the sheets, as they wrestle with sexual labels and expectations that simply do not fit: “Wearing those labels felt like sleeping in a bed that wasn’t mine,” they write. “As comfortable as the mattress was, and as clean as the sheets were, I woke up irritable, unrested.”(38) Khoo’s piece is a confident love story – a self-love story – which begins when they ingeniously convince their conservative mother to buy them a sex toy.

In Sally Breen’s ‘The Garden’ we slip between the senses to let “vivid colours draw vivid memories.” In it, a woman remembers versions of her grandfather’s garden and the versions of herself that wandered it. It’s a piece heady with synesthetic nostalgia, brilliantly coloured in “Kodachrome hues”:

“And all that remains is this orchard. Heirloom apples, small and crisp. I twist an apple, a revolution. And when it snaps the branch flicks back. Fruit fits snugly in my hand. It is this orchard that my grandmother adored. Blue Mountains. These blue days of sadness.” (28)

And in Amy Shapiro’s ‘Scheherazade’ we slip between forms as she takes the cage of a theatre script and shakes the bars to produce something else entirely – a dark vision of a mechanised future that explores that unfathomable space between consciousness and algorithm. “Suffering isn’t regression,” (55) Shapiro’s human protagonist tells her android interrogator. How might he believe her?

But it is the space between worlds – the space between cultures, traditions, histories and geographies – that beckons most insistently in Light Borrowers. “My people are the invisible fatalities / The footnotes of / Your people’s / History,” (209) laments Christine Afoa, of her Samoan heritage in ‘My People’ – a poem fearless, furious and proud.

“There is no X to mark my spot on this land,” writes Kiwi Shana Chandra, as she grapples with how conspicuously inconspicuous she feels visiting India:

“I know that if I enter this crowd, its surge will envelop me and I will be undetectable. I remember how scared I was at this thought when I first got off the plane in India, annoyed at all the brown faces, identical to mine. I am so comfortable wearing my difference in New Zealand and Australia that here I feel different, although I look the same as everyone else.” (190)

Worlds erased and escaped, lost and left, conjured and confining – Light Borrowers is anchored in the sensory details that bring worlds to life: the slow, night-time clacking of a basket of live snails; a lipstick kiss on a pillowslip; a sweaty city of “sleep deprived malcontents wearing badly fitting underpants”; a witty graffiti retort. “They zoom past the train line,” writes Jack Cameron Stanton, “and he sees the famous scrawl: GOD HATES HOMMOS, in black spray paint, with a neater, more curvaceous response spread beneath it in purple: BUT DOES HE LIKE TABOULI?” (83)

Those worlds are as individual as their authors; “inconsolably human” to borrow a phrase from Stanton. The triumph of Light Borrowers is that it has been constructed in, by and for, a diverse Australia, and it shows. This is an anthology that cares about the differences within Asian-Australian communities, not just between them. As Khoo writes: “Growing up as a second-generation Chinese Australian, I was constantly learning that the norm was actually just my norm.” (35) We are all living in our own, individual between place, Light Borrowers argues. Between the people we are, and the people we wish to be. Between ourselves and the world.

And yes, Light Borrowers is student work – the product of exuberance, ambition, earnestness and generosity. Every piece carrying the coiled energy of a seed, the shape of the author to come.

When people write of writing talent, there’s a tendency to equate youth with promise. We make list after list of bright young things to watch, and use ‘young’ as a synonym for ‘new’. Light Borrowers offers a magnificent rejoinder in the work of Echo Qin He, a woman determined to escape her inheritance of silence:

“I am in my 50s now. I don’t want to regret on my deathbed that I never gave it a go. It has taken me a long time. I have begun writing and my muscles are getting stronger day by day. Elements that used to be hard previously, that I didn’t know how to write about, now come more easily.” (160)

As a new migrant to Australia, writing – even reading – fiction felt like a luxury Echo Qin He could not afford, “making a living had to come first”. We can’t afford to lose or alienate voices like hers; new, urgent and carrying a lifetime – generations – of untold stories. We need more spaces like the UTS anthology, spaces that make room for new writers as they navigate that vital exploratory, playful space between searching for, and finding, their voice. A place where they can borrow a little light.

BEEJAY SILCOX came to writing circuitously; after narrowly escaping a life in the law, she has worked as a criminologist, agony-aunt, strategic policy boffin, and teacher of Americans. It is better for everyone that she now works on her own, as a literary critic and cultural commentator. Her award-winning short fiction has been published internationally, and recently anthologized in Best Australian Stories and Meanjin A-Z: Fine fiction 1980 to now. Incurably peripatetic, Beejay is currently based in Cairo, where she writes from a century-old building in the middle of an island, in the middle of the Nile.