Joshua Pomare reviews “A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work” by Bernadette Brennan

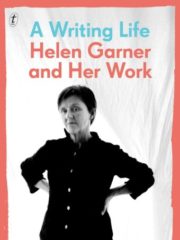

A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work

A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work

by Bernadette Brennan

ISBN: 9781925498035

Reviewed by JOSHUA POMARE

‘Garner has always been a boundary-crosser. Refusing the constraints of literary genre she has sought to write across and craft her own versions of them’ – Bernadette Brennan.

It is at these boundaries, the rough torn edges of art and artist that we understand our subjects best. A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work by Bernadette Brennan is a remarkably shrewd study of Garner’s work knitted with a tender representation of her personal life. Brennan dives into the murky grey depths that separate ‘literary critique’ and ‘biography,’ choosing instead the more ambiguous denomination of ‘literary portrait.’ This bifurcation of sub-genres might seem like literary posturing; such distinctions are often made by marketing teams as opposed to the author themself. However the language we use to segment books into genre is significant for readers and thus important to authors in terms of distribution and readership.

Finding an audience for books that exist outside of genres can prove a challenge. For Garner, this is familiar territory, early in her career she leapt from genre to genre, often landing in the areas between, and muddied the waters further by splicing non-fiction and fiction. For many readers taste determines reading preference and consequently genre. Savvy publishers seek to typecast authors early in their career to maintain a base of readers which to many is contrary to genuine artistic pursuit. The true artist has no consideration of audience, let alone the intricacies between sub genres, between fact or fiction, between form and style. Brennan’s previous book, The Works of Brian Castro, is a monograph, shelved in the recesses of academic libraries. However in A Writing Life Brennan shows she is equally as prepared to defy genre as her subject.

With over thirty pages of notes and references, it is clear Brennan is a fastidious reader and researcher however in spite of her academic background, she chooses to employ simple accessible language. At once she delves into the workings of Garner’s relationships, and reflects on the ways in which life events contextualise Garner’s work. Indeed many of the models for Garner’s fictional characters inhabited her personal life. Brennan probes the real events that inspired much of her work including the poignant and challenging relationship with her dying friend Jenya Osborne, which Garner explores in The Spare Room, and the resistance and confusion Garner faced from third wave feminism as a consequence of the The First Stone.

Garner possesses an immense self-awareness and an almost refreshing uncertainty that is absent in most non-fiction. James Wood in his profile for The New Yorker describes her is ‘a savage self-scrutineer.’ This introspection and ceaseless self-assessment allows the ‘I’ to creep into the narrative of her stories. Garner is forever querying herself and her motives, and documenting her findings. Here we find the origin of the genre fluidity she affords herself. Garner herself, as a prominent thread in the literary culture of Australia, tends to defy any delineation outside of the broadest labels: writer, artist.

Without Garner’s introspection and sincerity on the page Brennan may not have the access to paint a complete portrait. When in The Spare Room ‘Helen’ the character notes, “I had always thought that sorrow was the most exhausting of the emotions. Now I knew that it was anger,” a reader gets great insight into Garner’s own thoughts and feelings. Few artists are lucky enough to encounter subjects with such self-awareness and clarity of thought, fewer still will find one honest enough to share such insights.

One does get the sense that Brennan, although meticulous in her research and earnest in her approach, refuses to employ Garner’s imbuing of the text with the ‘I.’ Brennan at times seems to approach a counterpoint to Garner’s arguments without letting the thought reach the page as it forms in her own mind. Her voice is clear, objective and sensitive at times. The subtext, two years of conversations between Garner and Brennan, rises through the text softening the edges of the moral and ethical conundrums readers familiar with Garner’s non fiction may find themselves asking as they’re whisked along the summary of Garner’s work – each part of the novel represents in chronological order both a Garner novel and the period of Garner’s life in which the novel was written. One can’t help but consider Garner’s reflection and the fallibility of memory, and how this may indirectly shape the retelling of those long past episodes. This is another blurred line. It’s impossible for Brennan to maintain objectivity when such conversations are taking place, particularly considering the private letters Garner had shared with her.

Perhaps literary portraits require this input in the same way a painter might sit a subject down and constantly refer to her. If the subject moves, or changes expression the end product becomes a sort of amalgamation. We have twelve Helen Garners in A Writing Life; in the closing pages we get a final look at this ultimate Helen Garner in an email exchange with Brennan. It is here, in the final pages, that Brennan finds herself traipsing into the narrative. Brennan asks of Garner “Do you have another tale to tell me?” Garner recalls her recent experiences with her reading group, how the group grappled with a complex text, and in the penultimate line she asks Brennan, “Is that a story?”

A Writers Life, is published by Text Publishing in Melbourne. Text happens to be the publisher of all of Garner’s recent novels. It’s clear that Brennan has gone to considerable lengths to respect the wishes of Garner and has likely worked with Text for this reason. Garner has always been quite clear that she does not want a biography, however for this reader the biographical elements are the most important. Understanding who Helen Garner was at different stages in her life, how her opinions and worldview developed and of course how her life influenced her writing deepens one’s understanding of her work. Being such a devoted Garner scholar, Brennan possesses a knack for concision, clarity and an eye for detail but unlike Garner’s work we see it all from an arm’s length. Brennan is prepared to delve into Garner’s thoughts and motivations but not her own, certainly not with Garner’s characteristic candour. In this case, the artist and the art remain for the most part distinct. However, through dogged scholarly research, analysis, unparalleled access to Garners archive in the National Library of Australia and interviews with the subject herself, Brennan has weaved a complete and comprehensible portrait of Garner and her work. This is a book not only for Garner enthusiasts but Australian literature lovers in general.

JOSHUA POMARE is a writer living and working in Melbourne. His work has appeared in Kill Your Darlings, Meanjin and Takahe among others. He is also produces the podcast On Writing