Cher Tan reviews “Second City” Ed. Catriona Menzies-Pike & Luke Carman

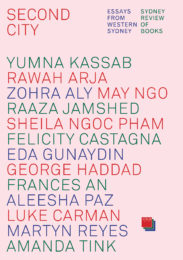

Second City: Essays From Western Sydney

Second City: Essays From Western Sydney

Edited by Luke Carman & Catriona Menzies-Pike

ISBN 978-0-6480621-3-4

Reviewed by CHER TAN

In ‘Second City’, the titular essay by Eda Gunaydin in Second City, an anthology of essays collected and published by the Sydney Review of Books, Gunaydin begins: ‘I spent the summer between 2013 and 2014 as many 20-year-olds do: working at a restaurant.’ It’s a sentence that includes as much as it excludes, echoing the popular internet phrase ‘if you know, you know’. The essay goes on to explore the ramifications of gentrification in Parramatta, alongside a certain gentrification of the self through education and upward mobility. With a stylistic panache and an erudite wit, Gunaydin goes on to ask, towards the end of the essay, ‘… if displacement did not begin five years ago but two hundred and thirty years ago, what use is there in attempting to freeze its current class and racial composition in amber?’ This mode of writing is something I’ve observed amongst writers on the so-called ‘margins’ in the last few years: as writers move away from the giddy nascence of a minoritised literature that is nevertheless situated inside an anglophone canon, narratives become less concerned with a centre and more interested in interrogating the complexities that arise from marginal conditions. Struggle is considered alongside joy, privileges alongside oppressions.

Second City is another anthology that adds to the burgeoning list of anthologies which display a range of writing in its variegated styles, tendencies and textures, particularly in an ‘Australian’ publishing landscape which has historically been exclusionary in both form and identity. Its subtitle, ‘Essays From Western Sydney’, is as sly as it is earnest, a marketing device that winks at you as much as it is true. Without belabouring the point (as I hope no readers of this publication have been living under a rock), Western Sydney is a location that has plagued the popular ‘Australian’ imaginary as a hotbed of chaos since the 1990s, when mainstream news media painted the area as one that was teeming with criminals and drug users. Even today, at the time of writing, certain (working-class and/or POC-majority) suburbs see an increase in police presence ostensibly to curb the spread of COVID-19 in Sydney but which we all know is a ruse to further criminalise bla(c)k and brown people.

As Felicity Castagna notes, in her essay ‘Hopefully the Future is Dark’, ‘The problem is that Western Sydney is a place but it’s also an idea. You can either write to that idea—think Struggle Street, Housos, The Combination, every protest you’ve ever seen on the rooftop of Villawood Detention Centre, every ‘dole bludger’ you’ve seen on A Current Affair—or you can write against it.’ I remember speaking with Gunaydin (full disclosure: she is a friend) about the popularisation of narratives ‘from Western Sydney’, where she observed that some writers from the area would play into preconceived notions of ‘Western Sydney identity’ while the dominant forces of Ozlit would look on with pity, guilt, shame and exoticised fascination. These forces are diminishing as ‘Australian’ publishing enters a new(er) epoch helmed by minoritised writers, creating a stronger understanding there is a need to move away from the centre, but doubtlessly in some circles it is still proliferating. Perhaps this is a paradox that can arise with critiquing marginalisation, which sometimes ends up entrenching those same ideas that resulted in the critique in the first place.

But the essays in Second City would rather dispose of those tendencies, and as a result they are as varied in subject as well as in style—what editor Luke Carman states in the book’s introduction ‘can be represented by no single politics, mindset, opinion, style, aesthetic or poetics.’ Frances An, in ‘(Feminist) Sages’, echoes the above-mentioned conversation with Gunaydin when she refers to ‘postcolonial cults who started every sentence with “as an [ethnic minority] …” and threw in terms like “Otherness” and “decolonise” to assert their status as messiahs of racial justice’, situated within a larger critique about left or left-adjacent movements that are exclusionary in their language and aesthetics even if they proclaim inclusivity. Further complexities are articulated in Sheila Ngoc Pham’s ‘An Elite Education’, an unpretentious personal narrative about the differences between her Vietnamese diaspora family and her husband Josh’s Anglo one, where the former is Liberal-voting and middle-class, and how she is ‘actually not the first in my family to receive a university education in this country’; whilst he is. Zohra Aly’s ‘Of Mosques and Men’ looks into the travails involved in her husband Abbas’s experiences building a mosque in the Christian-dominated area of Annangrove post-9/11, and May Ngo’s ‘Shopping Night’ expresses a vexed relationship to Western Sydney as a returnee.

Yumna Kassab’s ‘Borges and the Tiger’ stands out for its experimentalism, as it takes the reader through dream-like vignettes that analyse the work of Jorge Luis Borges and the perplexing allure of writing inside ‘the labyrinth’ (the library). Much like her debut collection of short stories, The House of Youssef, the author possesses a deft hand when it comes to crafting philosophical fables, resulting in a non didacticism that reveal intimacies as much as they allow for imagination to fill in the gaps, like how, as she puts it, reading Borges is ‘to be in a loop of symbols in endless conversation with one another’. In ‘Raise Your Needles in Defence of Public Knitting’, Aleesha Paz writes with a joyous energy, as she revels in making public what is commonly regarded as a private pleasure, while Martin Reyes’s ‘Excuse Me, Tabi Tabi Po’ is a light-hearted essay on his Filipino family’s superstitions alongside a serious contemplation of pre-colonial folklore and attitudes towards natural surroundings and land.

Castagna’s provocation about writing to or against preconceived ideas are at work in some of the essays in Second City: to Rawah Arja (in ‘An Introvert’s Guide to Surviving an Arab Family of Extroverts’), living in Western Sydney growing up was thought to ‘always going to be second best’; Raaza Jamshed (in ‘Muhammad’) recalls moving away from Bankstown because she doesn’t want her kids ‘to grow up as strangers to this country’, and to Ngo her childhood in Western Sydney ‘felt like we were so far away from everything—at least from anything that was interesting, away from the places where things were happening.’ Otherwise Western Sydney is hardly referred to at all; the words ‘Western Sydney’ appear in the anthology only 35 times (or thereabouts, otherwise I apologise for my ineptitude with numbers). The problem that Castagna points out is perhaps the biggest conundrum faced by minoritised writers and artists, that by virtue of our sexuality or our ability or our race or our socioeconomic position or the places in which we reside and/or come from, there is an impulse to either 1) explain, 2) smooth over, or 3) react against the status quo—that which places those preconceived images in the first place. Are there other ways to imagine? Indeed, as Castagna continues towards the end of her essay, ‘It is an invitation to undo the ways ‘things are done’ and invite alternatives into the equation.’

I won’t be so glib as to say that writing against preconceived ideas is easy, especially in a publishing landscape that is at once gatekept, looked at, and attended to by a certain section of society divorced from the so-called ‘real world’. It is even more difficult when they’ve bled into the dominant cultural narrative for it to appear as if it is the inherent truth. As George Haddad writes in ‘Uprooted’, an essay that contemplates identity as he is made to feel like an outsider in the inner city where he now lives: ‘How do I convey this cornucopia of identity to a stranger in a split second?’ Castagna even goes so far as to delineate her multi-faceted cultural background, but with a caveat: ‘None of that really says who I am though. It’s really only just a beginning.’ The fact that some essays in the anthology grapple with these concerns show that the playing field for more complex writing from what has been called ‘the subaltern’—at least within Australian literature—is undergoing a sea change, as many begin to move away from assimilationist desires and questions of what it ‘means’ to be such-and-such identity, instead focusing on minute joys and entanglements that would also rather entertain a devotion towards craft. As such, it would be prudent to consider what Gayatri Spivak once posed in a 1986 ABC Radio National interview about multiculturalism in Australia: ‘[…] the question “Who should speak?”is less crucial than “Who will listen?”’

Second City is one of those books at the precipice of this sea change. In this context, writers on the so-called margins can make the case again and again about why we should be seen and heard and read. But who are we trying to convince? Instead, like this anthology has exemplified, I urge us to continue delving into our myriad obsessions and complexities again and again until it becomes matter of fact.

CHER TAN is an essayist & critic in Naarm/Melbourne, via Kaurna Yerta/Adelaide & Singapore. Her work has appeared in the Sydney Review of Books, Kill Your Darlings, Overland, Runway Journal, The Lifted Brow, amongst others. She is an editor at LIMINAL magazine & the reviews editor at Meanjin.