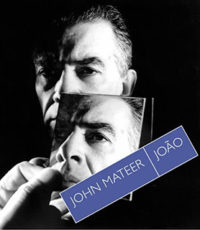

Bonny Cassidy reviews “João” by John Mateer

João

by John Mateer

Giramondo, 2017

ISBN:978-1-925336-62-7

Reviewed by BONNY CASSIDY

Speaking recently in Adelaide, the expatriate Australian theorist Sneja Gunew proposed that nations are the museums of identity. I took her to mean that, regardless of our status as foreigner/visitor or citizen/member, we tour them—we observe national identity being curated and performed. But can we resign from identifying our self through nationality; can we inhabit another kind of space that is not even partly defined by it?

In João, John Mateer insists that we – or, at least, that he – can. Writing in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Robert Wood concludes of the book: ‘This is its post-colonial hope, not that we forget empire but that we enter more fully into our own histories, experiences, and observations as a way to see where we are now.’ In the past, Mateer has been burned by cultural transgression. His response has been to go deeper into a meditation on displacement and self, to excuse his poetry from the responsibility or expectation of representing nationality.

At one point in João, the titular persona regretfully snaps at Gary Snyder for querying his nationali-ty, as if it could be a subject of interest beyond customs counters. For João, existence is a constant effort to find release from this static and collective identity. In this collection a postcolonial reading of Mateer’s poetics intersects with the Buddhist concepts with which he frames and guides the poems. In particular, these concepts refer to anattā or non-self, and rebirth. It is a fruitful, intri-cate combination that troubles the illusion of selfhood – and anything as lumpen as a nationalistic identity – through the arts of moving, seeing and expression.

Signifiers of Buddhism can be found in the architecture of the book. Its concentric, mandala-like arrangement seems to circumambulate the poems’ themes and personae. The first, long sequence of sonnets, ‘Twelve Years of Travel’ is bookended by images of mummified corpses: emblems of our corporeal emptiness. They are husks that reassure João of his travelling nature. The second, short sequence, ‘Memories of Cape Town’, opens and closes with images of ‘the Void’, or Śūnyatā. Here, Mateer provides a simile for João, who is a hollow persona; and also a larger concept to describe João’s motile way of moving through the world.

The nature of poetic voice in João is also informed by Buddhism. From the first sonnet, at a Japa-nese temple:

He closed his eyes, felt lost, slowly

recalling, within the depths of his dim, honeycomb body

[…]

and the monk,

blessing them with a long leafy branch, beckoned

him in to also pay homage to the transparent box,

the mummified saint. João heard: He could also be you…

João is narrated in the third-person and past tense. The voice is Mateer’s – or a simulacrum of authorial perspective – and it is addressed to João, Mateer’s alter-ego. This complicated handling of voice establishes the sense of an immediacy, a presence, that has passed into a cloud of resonance and metamorphosis; a ricochet between self and non-self. The persona of João is a delicious lyric tactic with plenty of critical potential. Mateer can make the character as thick or thin as he likes, and ‘explain’ nothing. This flexibility is poetry’s prerogative and it also serves Mateer’s themes. In João, the narrative construction is most agile when Mateer takes potshots at his persona’s cosmopolitanism and questions his ego: ‘Could that be the loss he needs to unremember? Who knows?’ It calcifies when he errs into the role of pervy, melancholy flaneur or clingy nostalgia: ‘João, like the watching servants, was alone, forgotten.’ Mateer’s attempts to maintain a suspended, ironic perspective on João is necessarily flawed. Some of these flaws are insightful, delivered with Mateer’s typical, self-parodying note; others, which I’ll turn to a little later, are less obviously knowing but remain consistent with the book’s theme of a constant struggle to exit self-interest.

In ‘Twelve Years of Travel’, each sonnet contributes a picaresque episode that defines place along the axis of time. João is Odysseus – or, more appropriately, Vasco de Gama – never returning home, because he recognises no such referent. Or perhaps he is Bashō, seeking home and family in always new forms and abodes. From Venice to Honolulu, Mateer defines place by inhabitation and by its having been witnessed: ‘Naples begins with two Nigerians on a train’. By the same rule, places disappear, like a page turning, when the protagonist decides to exit. In China:

Remembering the clay warriors, the horsemen and commanders, each

dedicated to the habit of war, that human selfishness,

João tells himself: ‘Become Nothingness, that golden wilderness!’

Rather than diaristic, though, the rhythm of the book is essayistic. The usual Mateer tropes are here: ghosts, doubles, shadows, angels (including Singaporean poet, Cyril Wong). While familiar, they do provide thematic motifs that remind us of Mateer’s philosophical concerns. The Shakespearean sonnet form achieves a neat topping and tailing of each episode, whilst creating a resonant echo. To his credit Mateer casually inhabits the form, frequently employing imperfect or even blank end rhymes when an image calls for release:

Deep in this tropical cinema João, somewhere,

swam with turtles and nymphs, followed endless, lava-strewn roads.

A limp conclusion, however, is sometimes the result of a forced rhyming couplet:

their feet sensing an intricate, inland maze.

Watching them on that mandala, João was silently, joyously amazed.

The romance of the sonnet, a form that always resembles a heaving and corseted bosom, is one example of the tension within João’s journeying. Mateer’s exoticisation of João’s travels is unashamed: every place is fantastic, such as the hellishly ‘baroque’ Naples and the ‘cinema’ of Hawaii’s landscapes. In this mode, Mateer is committed to reminding us that ‘poems are … only the heard, overheard’. But João’s view of the world – which is also the view held by the authorial narrator – is constantly threatening to narrow and stagnate. An appreciation of passing beauty becomes a reflection of João’s selfhood—his aesthetics, his tastes, his history. He struggles to abandon his African upbringing, the temptation to a sense of fixed belonging: ‘João left the dinner, yearning for Africa, unconfused.’ Similarly, the locus of cultural influence that has occupied Mateer’s recent books – Portugal and its empire – remains a constant touchstone throughout João.

While such texts including The Quiet Slave (2017) and Unbelievers, or the Moor (2013) achieve a sense of situated history – time on the axis of ideology, custom and language – the sonnets of João drag their anchors along. João tries to belong nowhere, owe nothing, and leave no trace of himself. While Mateer explores João’s struggle to achieve this, none of the secondary characters play an active part in the struggle, least of all João’s string of female lovers. In João, women are given a role that serves the persona’s suspension of self. The introduction of a woman leads several of the sonnets in ‘Twelve Years of Travel’, she often taking the form of a local guide or former lover. There is yearning, sentimentality, sympathy, even ‘fatherliness’ on the part of João, but the typical outcome of his meetings with women is sexual. Are they destinations of embodiment, then; reminders of mutability? The importance of sex to the book’s themes is undoubtable: it’s where João is reminded most constantly of being ‘a simple corpse, unhaunted fetish.’ But to undertake such a traditionally patriarchal deployment of female bodies and voices seems an inconsistently uncritical habit. Mateer’s representation of women has been questioned before. Paul Hetherington, reviewing Unbelievers for the Sydney Review of Books, remarked that it ‘risks being implicated in the exploitative tropes that it tries to subvert and critique.’ In João the accumulation of women’s names (which, like the locations in the book, generally appear once and then evaporate into memory) comes to resemble a diary of conquest—an irony of mode that I am unsure is deliberate. Significantly, they are rarely writers (one is a novelist, and João is mistaken for her husband) although some are permitted the role of angelic translators. Correcting him, humouring him, encouraging him, or gently ridiculing him, they may be intended as a parodic tool in João’s pathway to non-self; but, as Robert Wood has pointed out, ultimately women become yet more reflections of João.

This gendered tradition is impotent and tired, lacking reflexivity. Could Mateer have more deeply troubled the concept of stable selfhood; could he have widened the parodic gap between ego and alter-ego? Could he have brought them uncomfortably, searchingly closer? At one point João agrees that JM Coetzee is a ‘science fiction’ writer, a remark that comparatively highlights the safeness of Mateer’s collection. Perhaps Mateer’s commitment to owning João is crucial to the philosophy of discomfort behind these poems, yet it also keeps them slackly, comfortably tethered to authenticity.

This is a problem because authenticity of self is questioned by the very order of the book’s two parts. Its second sequence, the succinct ‘Memories of Cape Town’ features Mateer’s authorial voice, narrating the younger João through the perspective of the older João. The placement of the childhood memories after the long travel sequence, reminds us of ‘voidness’, that childhood is not a ‘key’ to a constant self. Rather, João’s memories (or the narrator’s memories of them) are focused on negations of fixity. In this childhood, João desired to ‘stow away’ in order to avoid becoming ‘castaway’. His model is an uncle Carlos, born in Rio and with a ‘tour guide mode, switching languages’ while driving his nephew through Cape Town: this is where young João learns to see ‘the world anew’. Here, also, is a grandmother from somewhere placeless ‘between India / and grim London’, who in João’s eyes is awesome for ‘being lost’: this is where he learns mournfully that he may not claim ‘to be African’. Here is where he learns cynicism about national futures, particularly neocolonial ones; and the ‘Queen’s English’ features more than once as a revelation ‘untrue’ identity. Finally, in these episodes from Cape Town, João learns of fate: the archetypal journey in which ‘Men roam the world to be fatherless’.

Is Mateer saying that existence is a realisation of a predictable plot? Is this his doubt? Is João’s wandering pre-determined by something other than karma? Or is there another, more consistent understanding of the idea? Its Old Testament view seems at odds with the book’s central references to non-self and voidness. As the last line of ‘Memories from Cape Town’ proffers: ‘Mother is space, and her depths you’. In light of the latter concepts, I do not read this ‘Mother’ as the feminised, Marian type, critiqued by Darren Aronofsky’s namesake film of 2017; instead, it seems appropriate to interpret ‘Mother’ as Saṃsāra—the cycle of birth and rebirth. Is Mateer, therefore, reinterpreting fatherlessness as a description of release from this cycle?

Here I want to return to Gunew’s gambit about nations. If nations are museums of identity, João is the ultimate museum-goer. Always guest and local, he tours destinations like vast, curious dioramas. He is rarely frightened of otherness, rather, he finds a source of common humanity and beauty wherever he goes. As Mateer reiterates: ‘We know João, our poet, loves museums, objects and their fame’. He loves aura in the Benjaminian sense of the word. He loves history, its cumulative layers and relational tangents. But this doesn’t mean he loves nationality, that is, collective identity based on citizenship.

Since Southern Barbarians (2011) Mateer has resolutely steered away from Australian referents and settings in his poems. I miss Australia in Mateer’s poetry; not because it somehow validates Australia’s national claim upon him, or because I want to recognise my own heritage in what I read, but because his Australian poems were fearless and grungy. In mode, they remind me of John A Scott’s contemporaneous poems, with their surreal scapes and meta-narration. In João, Mateer sets one poem in Victoria, at the Portuguese festival at Warrnambool—a celebration of pre-British identity in the Australian founding narrative, and a less familiar image of modern settlement. I enjoyed its collage of unfixed horizon points, its freedom from defining ‘multiculturalism’. Yet, in the manner of the book’s lesser style, it is a romantic sonnet to a lost love around which otherness is a pretty frame. I respect that Mateer’s voice has grown away from his earlier style, but I do wonder: what does João see when he visits Mateer’s home in Perth? Is it the globular suburbia of Corey Wakeling’s The Alarming Conservatory? Wakeling is a poet whose migrant parents inflect and also inflict his sense of Perth’s mediocrity; he also now sets himself elsewhere, looking back and forward to an Australia that is the subject of nostalgia, memory, long distance travel and calls. A comparative reading of space and place in these two recent books from Giramondo might yield interesting dialogues.

In João the stateless states of ex-patriate and Buddhist meet one another. They reveal one another. Being at home with being a constant visitor, learning how to be ‘lost’, is João’s path to enlightenment:

a passing through this world into deeper memory,

a searching for what’s beyond Elsewhere, an enquiry

into your previous lives

In this context, nationality is the most base illusion of selfhood and João’s physical travel is a portal out of the self. If he is a fantasy of fatherlessness, then João’s previous lives need not reside with the identity of his author-narrator. If he is a form or a product of meditation, João might reveal more than the current material body through which he passes. Fitfully, Mateer continues to craft proof of what does not exist.

BONNY CASSIDY is the author of three poetry collections, and lectures in Creative Writing at RMIT University, Melbourne. She is feature reviews editor of Cordite Poetry Review and co-editor of the Anthology of Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry (Hunter Publishers, 2016). Bonny’s essays of criticism and poetics have been published widely in Australia and internationally.