“Billy Sing”: A failed Transnational Hero by Beibei Chen

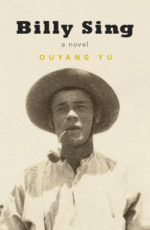

Billy Sing

Billy Sing

by Ouyang Yu

ISBN: 978-0-9953594-4-4

Reviewed by BEIBEI CHEN

Born in 1886 to an English mother and Chinese father, William ‘Billy’ Sing and his two sisters were brought up in Clermont and Proserpine, in a rural part of Queensland. Sing’s father was a drover and his grandfather was a Shanghai gold digger. Sing was a sniper of renown during Gallipoli war, his life has been remembered in both literary works, social media and an ABC TV mini-series, The Legend of Billy Sing. However, Billy’s Chinese ancestry, failed marriage and haunted war memories had not been fictionalized until Ouyang Yu published his novel, Billy Sing, in 2016.

It is probably the diverse racial perspectives and rich cross-cultural experience that drive Ouyang to write on this well-known but complicated historical figure and produce a new version. The story of Billy Sing in Ouyang’s eye is penetrating and darker, unsettling a renowned Chinese Australian sniper’s legendary but troubled life. In a sense, as a gifted writer, Ouyang flips the other side of Billy’s coin and finds the undiscovered part of him as a tragic heroic figure. Billy Sing is arguably Ouyang’s most successful literary novel. It is noteworthy for its prose-like narration, the bold imagination of Billy Sing’s private life and the way it illuminates themes of transnational identity and memory.

In Billy Sing, Ouyang utilises the Chinese cultural perception of “being a hero.” In Chinese culture, a hero has two faces: being honoured and worshipped in front of the public and being miserable and troubled in the private life. Billy Sing has the two faces and since many of the records have caught the first face, Ouyang smartly chooses to focus on the second.

The novel begins with a conflicting and unpleasant conversation indicating the troubled identity of Billy Sing: his friend Trevor mocked him by reciting “Oh, you cheap Chinaman, Chow, Pong, Ching-Chong, Choo-Choo, Cha-Cha, Wah-Wah, half-caste, mixed blood…” (13). Though historians may argue that there is no record of Billy Sing in history being bullied by white Australians the incident makes for a provocative fictional beginning for the novel. From the very first page, Billy’s identity is constantly at stake throughout the whole book.

Ouyang portrays Billy as a boy living in two conflicting cultures even as he grows up in Australia. As a teenager, Billy is deeply influenced by his father, a Chinese man who is always aware of the cultural dilemma of Chinese Australians, especially the second-generation migrants: “You were born of two truly incompatible cultures and languages, as incompatible as fire and water.” (19) Carrying life on with a doubled identity, Billy grows up to be a sensitive and confused self: “I constantly heard a voice saying to me: ‘You are no good mate. You are neither here nor there. You should have been born elsewhere. You were wrongly born. You were born wrong’ ” . (31)

Regarding himself as a “wrong” person does make young Billy feel hyper-sensitive and easily provoked. Tired of dealing with the angry moods triggered by drinking or gambling, he decides to enlist as a soldier, to fight for his adopted country. However, though regarding himself as an Australian, some of his fellow people despise him for his mixed blood. A Chinese saying goes like this: “Wars produce heroes”. Billy surely deserves the title of “hero” for his service in Gallipoli for Australia, his “father country”. But Ouyang digs further and darker: what war brings to Billy is endless trauma and haunted memories; memories which eventually bury Billy together with other soldiers in the grave of loneliness. After the war, Billy has to admit that “to save myself and my comrades, I had to kill and kill well.” (79) According to Sing’s inner monologue, it is obvious that his attitude towards war is quite negative: “We are all from elsewhere, originally at least, and are here killing total strangers who did nothing wrong”. (80) In the novel, his brave deeds of shooting enemies do not bring him pride. Instead, he thinks he is murdering innocent people — a killer rather than a hero. While history remembers Billy Sing as a war hero, this book challenges the notion of nationalism and portrays Billy as a person who detests war and death. He mocks himself: “my life had always been full of death, and success. Death and Success. Death Success. Deathuccess.”(99). Medals do not symbolize national pride, rather, they remind Billy of all the trauma haunting his subconscious.

The nightmare-like memories of killing, fighting and burying constantly challenge Billy’s after-war life and his perception of Australia is also transformed. Being a Chinese Australian, discriminated at by his peers, Billy cannot form a permanent sense of belonging, but during the war, his attitude is transformed: “If I could, I’d shoot the lot, end the war and pack up for home.” (82) He also has nostalgia towards the “kangaroo country” and the ideal life would be “shooting the roos and eating them, enjoying the waters when they rose each summer”. ( 91) Ouyang naturally merges Australian vernacular into the story of a marginalised Australian soldier. Numerous complex sentences are used to describe Australian bush scenes; killing kangaroos becomes a warm-hearted dream job, adding this novel more Australian flavour compared to Ouyang Yu’s other novels such as The English Class or The Eastern Slope Chronicle.

But when it comes to Billy going back with his wife Fenella, the plot is twisted by another difficult knot: Fenella is from ‘‘a family of non-blue-blooded Scots’’ and is reluctant to move to “the convicts’ country” even it is also a white world peopled with Anglo-Celtics. Ouyang’s thematic argument is that no country is free of discrimination simply because humans like to create divisions that exclude some people from belonging. At each occasion when Billy may find a “closure” to the ambivalence of his “shaky identity”, he is challenged again by his wife’s unwillingness to live in Australia. For a revenant like Billy, there is never an easy “going back”, because while battling with the uneasiness of being surrounded by ‘‘battle-worn and battle-maimed soldiers’’, he has another battle of living with a wife not keen on Australia.

On the subject of “home”, Billy has a fierce argument with Fenella: he regards Australia as a place where he has “peace and quiet” but to Fenella, Scotland is her home and “Nothing Australian is comparable”. (119) Billy feels shocked by Fenella’s denial of living in Australia and he also realises that to assimilate Fenella into an “Aussie” identity is nearly impossible. Billy is torn between the choice of returning to Europe where old memories haunt and harass him or to let Fenella go and he carries on with his life in “homeland”. Eventually, Billy Sing realises that his identity as a war hero cannot earn the respect of his wife; that for Fenella, the received stereotype of a degraded Australia cannot be easily shaken.

By unsettling the transnational marriage between a war hero and a Scottish girl with excessive national pride, Ouyang Yu transposes the issues of “national identity” to a world context and makes readers think about how seemingly straightforward questions. Though it is a slim novel of only one hundred and thirty five pages, Billy Sing certainly rediscovers a remote history and offers dynamic energy and tragic beauty. As a Chinese Australian male writer Yu’s voice helps to retrieve from the archives a delicate and lonely soul. Billy Sing, considered as a “heroic figure” is doomed to be a lonely man “persisting in his solitude”.

By indications in this book, Ouyang drives readers to predict that Billy Sing, a “killer”, “a murderer” and a “hero” has to live in the endless trauma and solitude, which leads to the ending of his tragic death in his beloved “country” and “home”. The reasons are obviously complicated: individual identity crisis, unhappy marriage, and racial discrimination. But fortunately, in this book, we sense humanity, and we sense the power of writing: to change history into a touching “his ‘story’”.

BEIBEI CHEN is currently working at Eastern China Normal University in Shanghai. She obtained her Ph.D degree from UNSW, Australia in 2015. She is a poet, literary critic and translator.