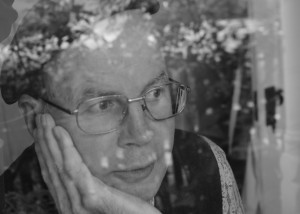

Peter Bakowski

Melbourne-born poet, Peter Bakowski, keeps in mind the following three quotes when writing poems ‐ “Use ordinary words to say extraordinary things’–Arthur Schopenhauer, “Writing is painting”– Charles Bukowski, anand “Make your next poems different from your last”–Robert Frost. Visit his blog http://bakowskipoetrynews.blogspot.com

Melbourne-born poet, Peter Bakowski, keeps in mind the following three quotes when writing poems ‐ “Use ordinary words to say extraordinary things’–Arthur Schopenhauer, “Writing is painting”– Charles Bukowski, anand “Make your next poems different from your last”–Robert Frost. Visit his blog http://bakowskipoetrynews.blogspot.com

Portrait of Jean Rhys, 1979

I’m too here,

a once exotic specimen,

wings burnt

by your glare.

I hobble

to my further drowning

in distasteful rooms,

to my further droning

in sympathetic ears,

to view the further sagging

of myself

in every looking-glass.

I’ve memorized English poems,

the songs chambermaids and chorus girls sing

when they are too alone,

what men say to convince you

up a creaking flight

of boarding-house stairs.

I know the difference between

flattery and fawning,

loneliness and solitude,

the cost of each kiss given,

each cheque cashed.

I’ve travelled,

left many places

ahead of the landlord’s footfall,

the crucifying wife.

I’ve known rooms,

their tapestry-hung walls

flecked by the light from chandeliers.

Other rooms too

of hard chairs

and the eating of gritty porridge,

each incomplete winter window

stuffed with newspaper.

I’m a chore to nurses,

muttering in my dressing gown,

smeared with lipstick,

stained with rouge,

propped up with a cane,

assisted to the toilet.

Only writing is important.

But truth and fiction

are too late for some.

I didn’t change the world

or myself.

London fog, personal fog,

I glimpsed something necessary in both.

What is life? A holding on and a letting go.

Some trip from dignity to despair

with more than a little

dancing and drinking in between.

I haven’t any conclusions,

only the books I wrote.

The nib of my pen

scratching for vermin,

preening my ruffled feathers,

fending off attackers,

including myself.

Now I dictate words

to last visitors—

David, Sonia.

It’s the blind throwing of coins

at a dented cup.

Some fall to the carpet.

I’m nearly dust.

Open the window.

Let the curtain

be my sieve.

Portrait of Erik Satie, Paris, October, 1899

Granted these days, my number of tomorrows unknown, I resist

Rushing. Leave me to stroll through Paris, which enchants

And confounds me, as would an octopus with feathers.

The way sunlight falls through the horizontal slats of a park bench

Interests me more than many paintings in the Louvre. Most art is

Too polite. It needs to poke its tongue out, pull its pants down. Children

Understand my music. Their ears are not full of hair, politics and

Dinner party gossip. Meanwhile I stroll, pause at a favoured café,

Eavesdrop, watch the ballet of waiters gliding from kitchen to table.

Visiting my mother

Your confined self,

your hallucinating self,

your blanket-clenching self,

pulse beneath your hosting skin.

You’re angry, marathon runner,

that the finishing line has been moved.

The way you lived,

the way you didn’t live,

each has exacted their price.

I move nearer to your bedside

but the syllable you strain

to shape, crumbles.

I look through family photo albums—

evidence of all your capable years.

Each dutiful visitor soon quietens.

Their platitudes have little use

in this disinfected room.

Sister Anneliese reads you a card

from a German friend

who no longer visits.

She pauses to wipe

the sweat from your brow.

Your former neighbour Jean

looks up at the wall clock,

rubs at a buckle on the strap

of her handbag.

I walk with her

away from your

diminished self,

along the long corridor

of the nursing home

and down the lift

into the vital world.