Martin Kovan is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which in recent years has been published in major Australian literary journals, as well as in France, the U.K., U.S.A., India, Hong Kong, Thailand and the Czech Republic. He completed graduate English studies with the U.S. poet, Gary Snyder, at UC Davis. He is completing a PhD in academic ethics and philosophy, and has volunteered in humanitarian work in South East Asia.

Martin Kovan is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which in recent years has been published in major Australian literary journals, as well as in France, the U.K., U.S.A., India, Hong Kong, Thailand and the Czech Republic. He completed graduate English studies with the U.S. poet, Gary Snyder, at UC Davis. He is completing a PhD in academic ethics and philosophy, and has volunteered in humanitarian work in South East Asia.

The Aid Worker

Long lines of people stretch as far as the first palm-trees on the horizon. The trees bend to one side, as if under-nourished, or importuning the earth. You have fed and sustained us, our roots are in your soil, but we are wanting. We need more, earth. Can you offer it, have you more to spare? The aid-worker is employed with the ground crew, meeting those first come from over the border. She sees the beseeching trees, hovering at an incline over the vertical figures beneath, and knows the thought is an idle fancy, mingling between their hazy contours and her own mind. Trees don’t make appeals to the earth; trees are just trees, growing, giving forth flower and fruit, diminishing, then dying.

Like the people themselves, she thinks: the burgeoning, the plenitude, the slow demise. She can see the long lines of figures, often in single file, traversing the raised, dirt paths between paddies. Smooth planes of low-lying water are lit blankly by the morning sun: sheets of electric light that flash, off and on, but convey no clear message. It has been raining for days; now the sky is a sheer blue above them.

The people are diminished, and many are infirm. Even the newborns, clinging to the girls’ arms, have begun the journey from a place of deprivation. The aid-worker’s job is to ameliorate the worst of the suffering, as much as it is in her power to. And her power is not something to be dismissed; she can even offer a little more than the earth can. Where the refugees have come from, they had water, pigs, flour and small crops. They enjoyed some natural, earth-given bounty. But it wasn’t enough, once the killing started. They needed more, then, than nature can provide.

They need the provision of food, and formula for the newborns, ointments and antiseptics the young mothers can’t find in the villages, even the well-stocked and well-situated ones. The people need medical aid and supplies, but still more, the specialized attention which knows how to apply the aid in effective ways. A certain kind of attention, it would seem, that they have not cultivated themselves. For they are poor, and have grown used to being deprived of things most others take for granted.

So that when the aid-worker meets the first of the young women, many of them carrying babies, who after descending the mountain ranges of the border have toiled across the vast flat and watered plains to her encampment in the green-zone, she is made aware, not for the first time, that she is the specialist, with a specialist’s skills, tending to people who themselves lack them. The girls are bent under loads, weighed down with babies or young children on their hips. Many of them are too young to be mothers; they carry nephews and nieces, the children of elder siblings, women who, the aid-worker knows, have died of unnatural causes.

The aid-worker notices, as she touches the children for the first time, relieving the girls of their various burdens, how beautiful the women are. Their strong, limpid eyes glow from smooth-skinned faces—weary, worn, still warm with the exertion of days and weeks on the mountain-paths. The aid-worker is neutral beside them, even nondescript: her pale limbs are concealed by synthetic fabrics to protect against insects and the fierce tropical sun, gloves and sometimes disinfectant on her hands, to ward off malign microscopic intrusions.

In her dun clothing, she feels diminished next to these exhausted, exquisite women, loosely covered in bright-coloured clothing. Their arms and wrists are finely-boned, adorned with childish jewellery, their smooth, dark feet often bare. The breasts of those bearing babies are also left bare, given to the open air. The women have no self-consciousness; they might not care if they did.

But this is how things are on the border: rich with contradiction, and the aid-worker has grown used to it.

Later that night, after the young women, and those who have followed them, have been treated and given shelter, fed and properly clothed, the aid-worker goes to the common area outside a tent-enclosure. There she meets with some of her colleagues: doctors and nutritionists, nurses and anaesthetists. All are tired but satisfied with the progress of the day. On the margins of the compound the palms bend and sway lightly in a mild breeze, hoopoes call from the adjacent stand of forest where, some have said, wild animals can sometimes be seen—elephants and even panthers.

‘So long as it’s not guerrillas, from over the border,’ one of them says, a man’s voice, jocular in the night. No-one can drink here, but many smoke, especially the European doctors, who might pride themselves on their immunity from the usual weaknesses. They are as if the gods of the place, who have come in from on high, and wield benign power over their domain. ‘I have heard all kinds of noises, in the night. Unearthly, incredible things,’ the same man says.

A voice says, ‘It’s the wild pigs, routing for food’.

Another opines, ‘Spirit-guardians of the place, disturbed in their rest.’

‘Don’t be silly,’ says a woman with a brassy voice. ‘It’s sex in the jungle. The call of the wild.’

‘Rhea the realist,’ the man says. ‘Always the basic needs with Rhea.’

‘And so?’ Rhea asks, lighting her own cigarette. ‘That’s our job here, isn’t it, to find the most realistic solutions?’

‘Yes,’ he replies. ‘You’re right. We’re the opposites of dreamers. We’re guardians of earthly sleep who allow the others to sleep in peace. Without us, they’ll come to harm in the night, and die.’

Birds cachinnate in the tree-tops; from deeper in the scrub surrounding, there are sounds of movement.

‘That’s putting it a bit archly, isn’t it?’ says a younger voice, a godling, his English still inflected with ivied walls, a consciousness of its own facility. ‘We’re only human,’ he says. ‘We need to sleep as well, you know. Speaking of which.’

He gets up and stretches his legs, as if to retire.

‘Wait, my young friend, not so soon. Let me ask you. We need to hear your opinion.’ It is the first man, with his garrulous, deep voice.

‘Oh, really?’

‘You have an expertise we older ones seem to lack.’

‘What would that be, great Hector?’ he playfully replies. His tone is ironic in a way apt to be misunderstood.

‘So, is that how well you think of me?’

The younger man laughs, and stretches long limbs, looking up at the black of the sky, dusted with constellations. ‘I was just poking fun. Probably not the wisest thing to do with the greyback of the pack, is it?’

‘Probably not, Achilles. It might look like you’re trying to diminish my authority.’

‘You could imagine that, if you chose to. It doesn’t really matter, though, does it?’

‘What does matter, in your view?’ Rhea says, blowing out plumes of smoke. The group sit otherwise in silence on the border, as if awaiting a tribunal. The people who have come to them from the other place sleep now, it seems peacefully, under plastic roofs and between hessian walls. The rain has stopped falling, though it might start again tomorrow.

‘What I mean,’ Achilles says, ‘is that if we are merely serving our allotted roles, then it’s not up to us, is it? To make the decisions, to call the shots? Someone else is doing all that.’

‘Oh, God,’ Rhea murmurs. ‘No politics, please. It’s too late in the day.’

The older man speaks again, interested now. ‘As if we were just—what? Puppets?’ Hector says, and makes a snorting sound. ‘You really are undermining my authority now!’ he says again, coughing on his cigarette.

‘Well, maybe we are. You just called me Achilles, after all. But my name is Tom.’

‘I’m sorry, Tom. Achilles seems to suit you better. I don’t know why.’

‘Exactly—I don’t know why I said it. Maybe someone else made me do it. I don’t know, I’m confused. I’m sorry, I have to sleep. Good night.’

‘And your advice, you’ll deprive us of that?’

There is an uncomfortable silence while those who have remained wait for his answer. But none is forthcoming. Tom, or Achilles, lifts his hand weakly to them, before departing the company.

***

The next day there is, as there always is, a lot to do. It is raining, and many of the lower-lying tents are inundated. Many of the people are sick, with flu and infections. The eyes of many of the older ones are inflamed with filmy sores. The children’s noses run, and because the people spit phlegm everywhere they go, illness moves fast. Some of those who have been more badly injured in crossing the mountains, who have met with mines, or whose wounds are too far advanced, must have limbs amputated.

Many others can barely walk and require crutches or wheelchairs, in short supply out here in the field. The latrines, too, are overwhelmed with use; food that has been prepared in rudimentary kitchens gathers flies, and children eat it sloppily, with their hands. Some of the older ones refuse to eat at all, as if they distrust food that has not come from the village, because it is foreign to them.

It is while she is talking with the interpreter, in the course of processing some new arrivals, that the aid-worker hears of a rumour. It has begun making the rounds of some of the refugees. The interpreter tells her of some of the first arrivals from a remote, lesser-known village, visited with massacre early in the outbreak of violence. They have recognised one of the newcomers: a young man, with a wound on his brow, who is generally silent and receives food and treatment without thanks. The aid-worker has come across him, but she has thought he is still in shock, the witness to events a teenager should not see.

‘No,’ the interpreter says. ‘They say he was one of the group of attackers—young men armed with machetes and knives. They came before dawn and left only those here now still alive.’ He has infiltrated the refugees, the interpreter says, to escape retribution over the other side, and to disappear on this.

‘He has slightly lighter skin,’ he says, ‘not as dark as theirs. He’s probably a half-caste.’

The words in the interpreter’s mouth are strangely of another time; he would probably have to describe himself as a half-caste as well, applying an old, foreign language to the people to whom he belongs, the once-colonised. But he has been away, in the West, and returned; he is one of a new class who are entitled to old words for ambiguous things.

‘They are fleeing,’ he says, ‘because they were never welcome.’ It is right that they should leave, he thinks, and return to the places they came from—just as the colonisers did. No-one likes having foreign interlopers on their native soil.

‘Have you spoken to him yourself?’ the aid-worker asks.

The interpreter shakes his head. ‘Not a good idea. If the others see me doing that, they’ll trust me less.’

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘But you’ll need to come with me, and report it. It will be confidential.’

In the afternoon, the aid-worker sees Tom, the young intern, working in the camp-area where the teenage refugee has been assigned. Tom tells her he’s seen nothing strange in the boy’s behaviour. ‘He sits quietly. Eats when he’s fed. Doesn’t talk to anyone.’

‘Some of them think he’s from the enemy side,’ she says. ‘Lured by the military…probably with favours. They think he’s a machete boy.’

‘He’s got the right kind of injury for that,’ Tom says. He’s cleaning hypodermic equipment, needles and syringes. ‘I treated him myself.’

‘Stay with him, Tom. Watch how he interacts. What the others say.’

‘OK. You’ll tell the chief, then?’

She nods. ‘Unless he’s heard already.’ The aid-worker leaves Tom alone with his equipment, and returns to the women who are under her charge. She tells the interpreter they might have to get the boy out of there at any moment.

‘Then I’ll have to go with him,’ he says. ‘There’s no-one else who can speak his language.’ Nor is there anyone who knows the people as well as he does.

‘What would they do?’ she asks him. ‘If they were able to?’

‘You don’t know?’ the interpreter says.

She doesn’t answer him. She’s spoken casually, as if they are discussing a revision of the roster. The women see him nod his head, and leave the aid-worker alone again. They wonder if the white woman and the dark man, almost as dark as they are, and so informal with each other, are in the privacy of their separate places secretly lovers. Where they come from, that would be reason enough for fear.

But under cover of darkness, where the staff gather to speak of the day’s events, such a thing seems more possible, and even the fear something to surmount. There is always escape, after all. The question of the teenage boy is broached, eventually, by Tom.

‘We ought to evacuate him, tomorrow,’ he says. ‘Anywhere but keep him in the camp.’ No-one speaks while the question hangs in the dense, humid air. It might rain again, that night; if it does, it might not stop for days.

The head of operations takes this in, calmly. He has begun, now, to smoke cigars; the aromatic smoke loops among the loose circle, sitting in a darkness filtered by the artificial light of lamps coming from nearby tent-enclosures. ‘I need my people here,’ he says. ‘We don’t have the resources to send people off on goose-chases.’

‘It’s a question of safety, not goose-chases,’ Tom says. ‘Can we afford that?’

‘You again. My friend Achilles. The humanitarian of high repute. No-one disagrees with you.’

‘I can go tonight, then.’

‘You can stay here, with everyone else.’

‘I’d prefer not to.’

Hector lifts his heavy eyebrows. He sighs. ‘We’ve been tasked to help these people, medically. That means all the people. It doesn’t matter where they’ve come from, or what they’ve done before. We’re not here to judge people for alleged crimes. We treat their bodies and their minds. We’re tasked to save their lives, not to spirit them to secret locations in the middle of the night. No-one knows who this boy is. It might be just a rumour. These people are half-crazed, in shock. They don’t know what they’re talking about. The boy with the machete wound will stay here. I’ll see to him myself. No-one will dare to touch him then.’

‘You don’t know what you are talking about, Hector,’ the young intern says. ‘We train their armies. We sell them the guns.’

‘And so? What’s that to us? We can’t decide how they use them. We’re only here to keep them alive, if we can.’

‘If he stays in the camp he’ll be killed within days.’

‘Who asked you for your advice? Did anyone?’

‘Actually, they did. You did. But I’m just an intern. My job is to learn from you.’

‘Well, in that case,’ Hector says, ‘I have something to teach. If I hear more disrespect from you I’ll throw you across that border just over there, and leave you to the hospitality of that guerrilla army you probably sympathise with. You probably imagine they are your friends in the moral fight, because you are a nice, intelligent boy. But they’ll put you in a cage, feed you rotten birds and mice, and make you shit in your clothes. Do you understand? Then they’ll call me on their mobile-phones and demand I give them half a million bucks from our overflowing coffers, before sending you back to me. And I won’t hesitate—after hesitating just a little. Because I’ll ask myself, is clever Achilles worth that much? There are plenty like you, from your fancy colleges, that I can pick out of the pool any time, and maybe Achilles is really dispensable, maybe his privilege means nothing, and he is only a little scrap—a scrap of pretentious crap. Do you like the sound of that, Achilles, or Tom, or whoever the fuck you are? Do you like that—how literary it is? Now go and sleep your precious sleep of the intern, knowing as you always have that there are those who are more powerful than you who can be trusted to protect you and take care of you, should you come to harm from the wild animals of the night.’

Hector puffs furiously on his cigar and he really could be blowing hurricanes of wrath across the millennial heavens. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow, young man. You’ll come to my quarters, at a time to be decided. For now, you are suspended from further duties. Now get lost, get out of here.’ He raises himself from his camp-chair, and throws the half-smoked cigar into the murky edge of the enclosure. But as soon as the younger man is gone, he smiles desperately. ‘Well, that was a bit of fun, wasn’t it? You all enjoyed that, didn’t you?’ Hector’s voice trembles, he is embarrassed by his outburst, and looks like he might break into tears. ‘A good thing it’s all play-acting, as he says,’ he adds.

‘I think it’s time you took a rest,’ Rhea says.

‘I do too, my dear,’ he says, relieved at his rescue. ‘What do you have in mind?’

‘Why don’t you come to my tent, and I’ll let you know there?’

An expansive, celestial smile traverses his broad Olympian features. ‘For real?’ he says, his eyes dilating with regained power.

‘As real as it gets,’ she says, stubbing out her cigarette.

In the morning, the interpreter visits the aid-worker again. ‘I was with the villagers just now,’ he says. ‘More than one of them remember him. It’s no mystery to them. He’s probably an orphan. Should I speak to him?’

‘Are they talking with any others? People from the other villages?’

‘Not as far as I can tell. But they will, when things get restless. As they’re bound to do.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘They always do, don’t they?’ he smiles. ‘Why don’t we go to lunch,’ he adds. ‘You’ve been working hard enough.’

But the aid-worker decides to stay in, and write her own account of events. In a lined notebook she writes of the cloying air, the mosquitoes, the sense of moist inevitability, seeping into everything. She is waiting for the rain to break, again, like a new mother with her waters. There is water everywhere, in her picture of things.

The picture includes the interpreter, the machete boy, and Tom, and the portentous leader of their crew, like figures in a film. But not herself, she stands outside it: to herself, she is just a worker, an aid-worker, in a place of need, and of privation. Everyone needs her; but no-one really needs her. Most of the people there barely remember, or even know, her name. Even in a fiction she would probably go nameless.

Like the interpreter, and the machete boy, who are perhaps her confreres. If she ran away with the interpreter, she wonders, would they set up a life together, somewhere, with the machete boy as an adopted son? There’s no reason why not, she thinks, it would be an acceptable outcome.

In her world, however, it would be a make-believe. What would she say to the suspected killer, a teenager with blood on his hands, and whose language she doesn’t speak? Would he care what she has to say, any more than anyone else would?

When she goes on rounds of the different wards, she takes care not to look in on the boy. No attention should be drawn to him. She agrees with Tom, and would help him make the escape, if anyone asked. But no-one asks her what she thinks, not even the interpreter. They expect her to do her job, dimly, as befits her bland and mousy appearance. Like someone in a lab, or a primary school, or a factory, doing a dim and minor job that few others want to do. She decides to go and find the interpreter, and take him up on his offer of lunch.

The interpreter is meeting with the teenager in his corner of the camp. Nor can she find Tom, who has been taken off work and is confined to his camp quarters. It is only after nightfall, when the electric lamps begin to come on, and candles are burning among the bivouacs of the refugees, many of whom prefer to sleep outside, that she hears there has been a disturbance.

One of the women comes to her, still wearing the ragged clothes of her journey over the mountains. She points briefly to her chest and shakes her right hand in a fluid, dismissive motion: there is something wrong with the heart, hers or another’s the aid-worker can’t tell. The woman looks quickly back over her shoulder, and points towards the authorised area of camp administration and central quarters.

The aid-worker goes there and among the doctors’ inner circle meets Rhea, regally taking control of the crisis. She gathers that someone has died: the head of operations, the hero Hector, found dead in his bed. She is not alarmed by the news. No-one has seen anything, there is no evident injury, he might have had a heart-attack.

But she is not so sure. Why would a healthy man in his prime, smoking cigars with a flourish only the night before, suddenly die without any sign? Rhea suggests that the aid-worker return to work, a meeting will be convened later. Returning to her designated wards, she sees the interpreter rushing up to her. ‘I can’t find him anywhere. The boy. He’s gone.’

She takes hold of his arm. ‘The head is dead,’ she says.

The interpreter nods, still breathless. To him it seems a clear thing, to make the obvious inference.

‘But there’s no sign,’ she reminds him. ‘No blood, no wound, nothing even broken. No machete blows.’

‘People can be strangled,’ he says. His hair is awry and sweat beads on his face, as if he’s been running, wildly, in circles, like someone searching for the end of a labyrinth.

‘He was found in a deep repose.’ The words coming from her mouth are as if spoken by someone else, she is sure she has never used the word repose before, it seems completely alien to her.

***

When Tom has entered the head tent he is already well-armed and mentally prepared, it is not at any arranged hour, it is premeditated but spontaneous and the head of operations is still in his bed, waking from a nap, he is surprised in his domestic repose, an intruder in his sanctum, and the boy, the intern boy, like Achilles with his spear, coming in without warning as if to surprise him in his sleep, and Hector says, ‘Who do you think you are coming in like that?’

‘You called, and I had nothing else to do,’ Achilles tells him.

‘I am still in my bed,’ Hector says. ‘You have not been invited here.’

‘I believe I was. But you can stay there, it is better that way.’

‘Better for what? For whom?’

‘Better for you, and for all of us,’ Achilles repeats, his normally calm eyes adjusting to the weak light of the sunken place. ‘Not much of a place to die, Hector. You probably had better plans for yourself. Instead of rotting in an obscure grave, on the border of someone else’s civil war, none of your business after all, just here to save the sick and disenabled, the ones who can’t save themselves. The irony, doctor, is that you can’t save yourself either. No-one can save you, now. Don’t worry, it will be swift and almost without pain. The only pain will be in leaving. In leaving this place of privation. Returning to your abode of the gods.’

Achilles lifts the large syringe held down by his side and quickly plunges the needle into the chest of the other man, its full dose of hydromorphine discharged directly into the heart.

‘And there will be no mark to show,’ Achilles says. ‘Maybe just a little blood, but I’ll clean it up. Barely a surface wound.’ Hector lies still in the bed, a large smile gradually transforming his face, that could come from a final wound of pride.

‘You are good, Tom. I could trust you after all, to do the right thing. Now go back to work, and leave me.’

Achilles looks down at him for a moment longer.

‘One day you’ll be where I am now,’ the doctor says. ‘And you’ll know that it’s right, like this.’ Achilles takes a last look at the doctor before leaving his sunken tent. The sun is high again, outside; the paddies stretch away in every direction. He can hear the noise of people, preparing food, moving from place to place. There are people talking, with urgency, engaged in life. There are still all the others to save, and those not to. Only a god can know how to choose between them, he thinks.

But Tom, or Achilles, as he has said, is only a kind of functionary, so he could not be expected to know. As he moves towards the people, he sees the aid-worker coming towards him. ‘I need you to do something for me,’ he says to her. ‘Can you help?’

The aid-worker nods, looking past him.

Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.  Empty Chairs

Empty Chairs

The Stolen Bicycle

The Stolen Bicycle Lunar Inheritance

Lunar Inheritance NICHOLAS JOSE has published seven novels, including Paper Nautilus (1987), The Red Thread (2000) and Original Face (2005), three collections of short stories, Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (a memoir), and essays, mostly on Australian and Asian culture. He was Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy Beijing, 1987-90 and Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, 2009-10. He is Professor of English and Creative Writing at The University of Adelaide, where he is a member of the J M Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice.

NICHOLAS JOSE has published seven novels, including Paper Nautilus (1987), The Red Thread (2000) and Original Face (2005), three collections of short stories, Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (a memoir), and essays, mostly on Australian and Asian culture. He was Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy Beijing, 1987-90 and Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, 2009-10. He is Professor of English and Creative Writing at The University of Adelaide, where he is a member of the J M Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice. Middle of the Night

Middle of the Night Xia Fang, born in 1986, is a bilingual poet and translator. She has published two collections of translated poems and her own poetry has appeared in

Xia Fang, born in 1986, is a bilingual poet and translator. She has published two collections of translated poems and her own poetry has appeared in  Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu

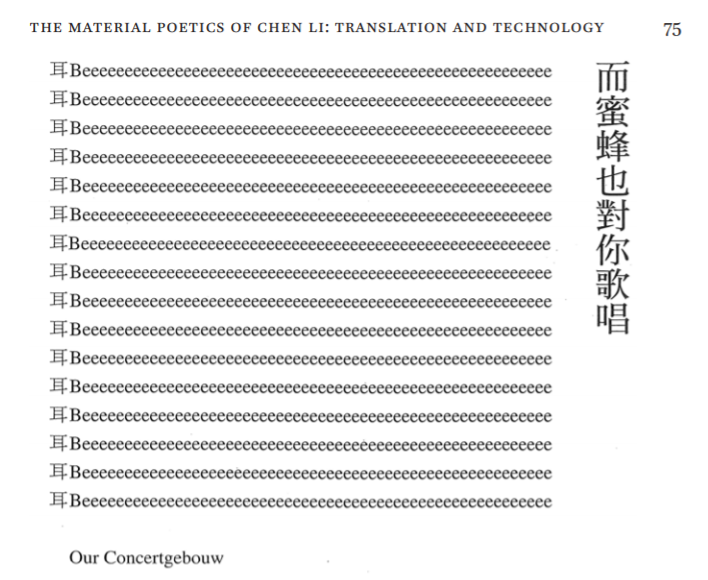

Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Xiaoshuai Gou was born and raised in China. He has been working as a teacher of English and Mandarin as a second language and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of South Australia.

Xiaoshuai Gou was born and raised in China. He has been working as a teacher of English and Mandarin as a second language and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of South Australia. Sanaz Fotouhi is currently the director of Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. Born in Iran, she grew up across Asia and holds a PhD in English literature from the University of New South Wales. Her book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution was published in 2015 (I.B. Tauris). Her stories and creative fiction are a reflective of her multicultural background. Her work has appeared in anthologies in Australia and Hong Kong, including Southerly, The Griffith Review, as well as in the Guardian UK and the Jakarta Post. Sanaz is one of the founding members of the Persian Film Festival in Australia as well as the co-producer of the multi-award winning documentary film, Love Marriage in Kabul.

Sanaz Fotouhi is currently the director of Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. Born in Iran, she grew up across Asia and holds a PhD in English literature from the University of New South Wales. Her book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution was published in 2015 (I.B. Tauris). Her stories and creative fiction are a reflective of her multicultural background. Her work has appeared in anthologies in Australia and Hong Kong, including Southerly, The Griffith Review, as well as in the Guardian UK and the Jakarta Post. Sanaz is one of the founding members of the Persian Film Festival in Australia as well as the co-producer of the multi-award winning documentary film, Love Marriage in Kabul. Encounters with Asian Decolonisation

Encounters with Asian Decolonisation Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a Chinese statesman, writer and philosopher of the Song dynasty. A significant portion of his career was spent working on China’s defences along the North-western border, which inspired the theme of loneliness in his writings. His best-known poems contrasted his experience of solitude and homesickness with a sense of duty to his country and people.

Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a Chinese statesman, writer and philosopher of the Song dynasty. A significant portion of his career was spent working on China’s defences along the North-western border, which inspired the theme of loneliness in his writings. His best-known poems contrasted his experience of solitude and homesickness with a sense of duty to his country and people. Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) lived during the Song dynasty and was considered one of the most accomplished woman poets in Chinese history. Many of her poems intimately reflect her experiences of love, loss, fear and uncertainty living in a war-torn China.

Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) lived during the Song dynasty and was considered one of the most accomplished woman poets in Chinese history. Many of her poems intimately reflect her experiences of love, loss, fear and uncertainty living in a war-torn China. Yunhe Huang is a Chinese writer based in Australia. She has written poetry and prose in both Chinese and English, using a variety of genres from Song-dynasty

Yunhe Huang is a Chinese writer based in Australia. She has written poetry and prose in both Chinese and English, using a variety of genres from Song-dynasty  Wanling Liu (born 1989, China) completed her MA in Translation and Transcultural Communication at the University of Adelaide. She is a literary translator and teaches translating and interpreting in Adelaide. She has developed a passion for performance poetry and storytelling events and has won spoken word prizes with her poetry published in local anthologies.

Wanling Liu (born 1989, China) completed her MA in Translation and Transcultural Communication at the University of Adelaide. She is a literary translator and teaches translating and interpreting in Adelaide. She has developed a passion for performance poetry and storytelling events and has won spoken word prizes with her poetry published in local anthologies.

Martin Kovan is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which in recent years has been published in major Australian literary journals, as well as in France, the U.K., U.S.A., India, Hong Kong, Thailand and the Czech Republic. He completed graduate English studies with the U.S. poet, Gary Snyder, at UC Davis. He is completing a PhD in academic ethics and philosophy, and has volunteered in humanitarian work in South East Asia.

Martin Kovan is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which in recent years has been published in major Australian literary journals, as well as in France, the U.K., U.S.A., India, Hong Kong, Thailand and the Czech Republic. He completed graduate English studies with the U.S. poet, Gary Snyder, at UC Davis. He is completing a PhD in academic ethics and philosophy, and has volunteered in humanitarian work in South East Asia. HC Hsu is author of the short story collection Love Is Sweeter (Lethe) and essay collection Middle of the Night (Deerbrook), which has been nominated for the Housatonic Award, CALA Award and Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature. Memoir competition winner and The Best American Essays nominee, he has written for Pif, Big Bridge, Iodine, nthposition, 100 Word Story, China Daily News, Epoch Times, Words Without Borders, and many others. He has served as interpreter for the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China, and his translation of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo’s biography Steel Gate to Freedom was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2015.

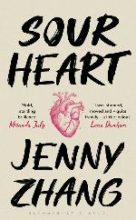

HC Hsu is author of the short story collection Love Is Sweeter (Lethe) and essay collection Middle of the Night (Deerbrook), which has been nominated for the Housatonic Award, CALA Award and Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature. Memoir competition winner and The Best American Essays nominee, he has written for Pif, Big Bridge, Iodine, nthposition, 100 Word Story, China Daily News, Epoch Times, Words Without Borders, and many others. He has served as interpreter for the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China, and his translation of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo’s biography Steel Gate to Freedom was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2015. Sour Heart

Sour Heart

Carielyn Tunion aka ALIENCRY is a multidisciplinary artist & serial story peddler with experience in visual arts, illustration, screen production & creative content production. Her focus is on community empowerment through representation, decolonisation practice, and creative collaboration. Her work has appeared in The Experience Magazine, ISMS-zine, Vertigo, 2TheFront Zine. She has exhibited at Lowbrow Denver Pintastic Exhibition, Colorado, Amber Rose’s Slutwalk, LA. This video was part of the SAD N ASIAN group show in New York, and at a @kaleidopress event in 2017.

Carielyn Tunion aka ALIENCRY is a multidisciplinary artist & serial story peddler with experience in visual arts, illustration, screen production & creative content production. Her focus is on community empowerment through representation, decolonisation practice, and creative collaboration. Her work has appeared in The Experience Magazine, ISMS-zine, Vertigo, 2TheFront Zine. She has exhibited at Lowbrow Denver Pintastic Exhibition, Colorado, Amber Rose’s Slutwalk, LA. This video was part of the SAD N ASIAN group show in New York, and at a @kaleidopress event in 2017. Ella Jeffery’s poetry, reviews and essays have appeared in Meanjin, Westerly, Cordite,

Ella Jeffery’s poetry, reviews and essays have appeared in Meanjin, Westerly, Cordite, Michelle Cahill’s short story collection Letter to Pessoa won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing.The Herring Lass is her most recent poetry collection. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland Review, Meanjin, Island, Antipodes, Best Australian Poems and the Forward Book of Poetry, 2018. She co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets with Adam Aitken and Kim Cheng Boey, and Vagabond’s deciBels3 with Dimitra Harvey. With Professor Wenche Ommundsen she was a University of Wollongong conference delegate at Wuhan University’s 2017 ‘China: One Belt, One Road.’

Michelle Cahill’s short story collection Letter to Pessoa won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing.The Herring Lass is her most recent poetry collection. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland Review, Meanjin, Island, Antipodes, Best Australian Poems and the Forward Book of Poetry, 2018. She co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets with Adam Aitken and Kim Cheng Boey, and Vagabond’s deciBels3 with Dimitra Harvey. With Professor Wenche Ommundsen she was a University of Wollongong conference delegate at Wuhan University’s 2017 ‘China: One Belt, One Road.’ Billy Sing

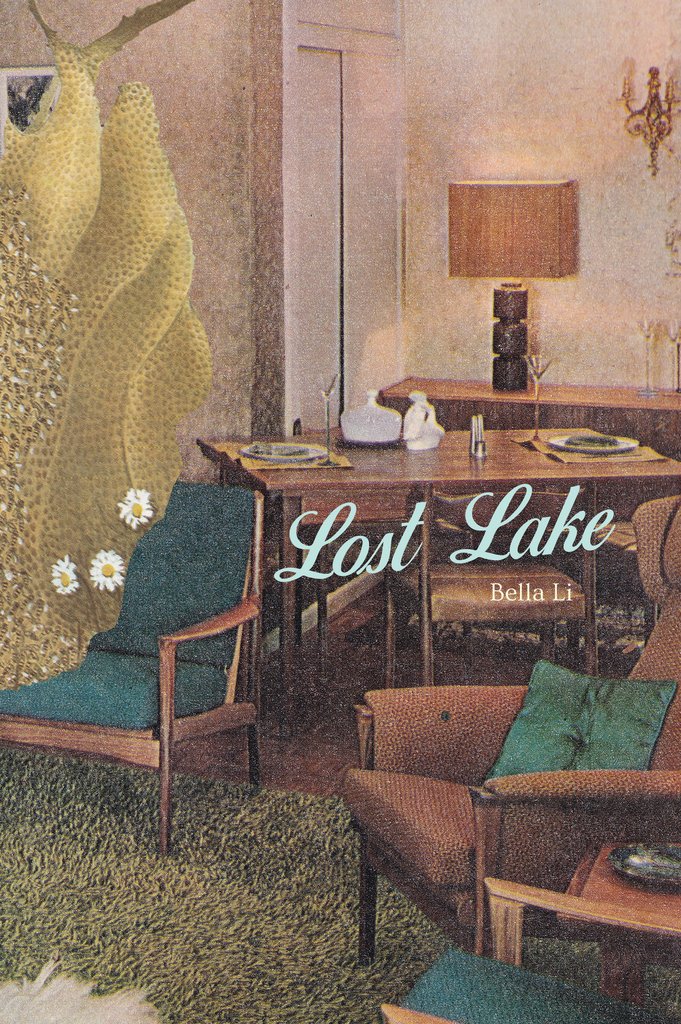

Billy Sing Argosy and Lost Lake

Argosy and Lost Lake

May Ngo is a researcher in the social sciences, focusing on development in Cambodia. Her other interests include theology, migration, diaspora and literature. She is also developing her father’s memoirs of his time with the Vietnamese communist army as a novel. She has a blog at The Violent Bear it Away (https://theviolentbearitaway1.wordpress.com/) and tweets at @mayngo2

May Ngo is a researcher in the social sciences, focusing on development in Cambodia. Her other interests include theology, migration, diaspora and literature. She is also developing her father’s memoirs of his time with the Vietnamese communist army as a novel. She has a blog at The Violent Bear it Away (https://theviolentbearitaway1.wordpress.com/) and tweets at @mayngo2 Lynda Ng was born in Wollongong. She is a graduate of the NIDA Playwrights Studio and the editor of

Lynda Ng was born in Wollongong. She is a graduate of the NIDA Playwrights Studio and the editor of  Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection, Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor,] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection, Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor,] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Emily Yu Zong has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Queensland, where she remains an honorary research fellow. Her doctoral thesis on Asian Australian and Asian American women writers was awarded the 2016 UQ Dean’s Award for Outstanding Higher Degree by Research Theses. Her research interests include ethnic Asian literature, gender and sexuality, and literature and the environment. She has published academic articles, interviews, and book reviews in Journal of Intercultural Studies, JASAL, New Scholar, Mascara Literary Review, and Australian Women’s Book Review.

Emily Yu Zong has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Queensland, where she remains an honorary research fellow. Her doctoral thesis on Asian Australian and Asian American women writers was awarded the 2016 UQ Dean’s Award for Outstanding Higher Degree by Research Theses. Her research interests include ethnic Asian literature, gender and sexuality, and literature and the environment. She has published academic articles, interviews, and book reviews in Journal of Intercultural Studies, JASAL, New Scholar, Mascara Literary Review, and Australian Women’s Book Review. Janet Jiahui Wu is a visual artist and writer of fiction and poetry. She has published in Voiceworks Literary Magazine, Cordite Poetry Review and Rabbit Poetry Journal. She currently resides in Adelaide, South Australia.

Janet Jiahui Wu is a visual artist and writer of fiction and poetry. She has published in Voiceworks Literary Magazine, Cordite Poetry Review and Rabbit Poetry Journal. She currently resides in Adelaide, South Australia. A.J. Carruthers is an Australian-born experimental poet, literary critic and lecturer in the Australian Studies Centre at SUIBE in Shanghai. He is author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems, 1961-2011 (Palgrave 2017), a book of literary criticism that examines five North American long poems and their relation to musical structures and musical scores. The first volume of his epic poem, AXIS Book 1: Areal, was published in 2014 (Vagabond). Opus 16 on Tehching Hsieh is a downloadable eBook from

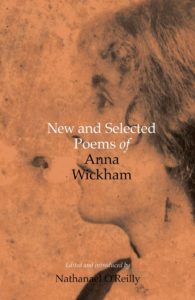

A.J. Carruthers is an Australian-born experimental poet, literary critic and lecturer in the Australian Studies Centre at SUIBE in Shanghai. He is author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems, 1961-2011 (Palgrave 2017), a book of literary criticism that examines five North American long poems and their relation to musical structures and musical scores. The first volume of his epic poem, AXIS Book 1: Areal, was published in 2014 (Vagabond). Opus 16 on Tehching Hsieh is a downloadable eBook from  New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham Hidden Words Hidden Worlds:

Hidden Words Hidden Worlds:

Winner:

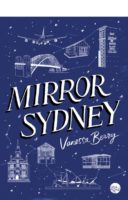

Winner:  Winner: Mirror Sydney by Vanessa Berry (Giramondo)

Winner: Mirror Sydney by Vanessa Berry (Giramondo) Winner: Shaping the Fractured Self Ed. Heather Taylor-Johnson (UWA Publishing)

Winner: Shaping the Fractured Self Ed. Heather Taylor-Johnson (UWA Publishing) The Lost Culavamsa: or the Unimportance of Being Earnest

The Lost Culavamsa: or the Unimportance of Being Earnest These Wild Houses

These Wild Houses Eunice Andrada is a Filipina poet, journalist, lyricist and teaching artist based in Sydney. Featured in the Guardian, CNN International, ABC News and other media, she has performed her poetry in diverse international stages, from the Sydney Opera House and the deserts of Alice Springs to the United Nations Climate Negotiations in Paris. During a residency in Canada’s prestigious Banff Centre, she collaborated with award-winning jazz musician and Cirque du Soleil vocalist Malika Tirolien. She has also shared her verses with celebrated composer Andrée Greenwell for the choral project Listen to Me. Eunice co-produced and curated Harana, a series of poetry tours led by Filipina-Australians in response to the Passion and Procession exhibition in the Art Gallery of NSW. Her poems have appeared in Peril, Verity La, Voiceworks, and Deep Water Literary Review, amongst other publications. She was awarded the John Marsden & Hachette Australia Poetry Prize in 2014. In 2018, the Amundsen-Scott Station in the South Pole of Antarctica will feature her poetry in a special exhibition on climate change. Flood Damages (Giramondo, 2018) is her first book of poetry.

Eunice Andrada is a Filipina poet, journalist, lyricist and teaching artist based in Sydney. Featured in the Guardian, CNN International, ABC News and other media, she has performed her poetry in diverse international stages, from the Sydney Opera House and the deserts of Alice Springs to the United Nations Climate Negotiations in Paris. During a residency in Canada’s prestigious Banff Centre, she collaborated with award-winning jazz musician and Cirque du Soleil vocalist Malika Tirolien. She has also shared her verses with celebrated composer Andrée Greenwell for the choral project Listen to Me. Eunice co-produced and curated Harana, a series of poetry tours led by Filipina-Australians in response to the Passion and Procession exhibition in the Art Gallery of NSW. Her poems have appeared in Peril, Verity La, Voiceworks, and Deep Water Literary Review, amongst other publications. She was awarded the John Marsden & Hachette Australia Poetry Prize in 2014. In 2018, the Amundsen-Scott Station in the South Pole of Antarctica will feature her poetry in a special exhibition on climate change. Flood Damages (Giramondo, 2018) is her first book of poetry. Elif Sezen, born in Melbourne in 1981, grew up both here and in Izmir, Western Turkey. She settled in Melbourne in 2007. Also an interdisciplinary visual artist, she writes original poetry in English and in Turkish. In 2014 she published her Turkish translation of Ilya Kaminsky’s acclaimed book Dancing in Odessa; her own first collection of experimental short stories in Turkish, Gece Düşüşü (‘Fall.Night.’), was published in 2012. Elif’s collection of poems Universal Mother was recently published by Gloria SMH Press, and she also published a chapbook The Dervish with Wings early 2017. She holds a PhD in Fine Arts from Monash University. www.elifsezen.com

Elif Sezen, born in Melbourne in 1981, grew up both here and in Izmir, Western Turkey. She settled in Melbourne in 2007. Also an interdisciplinary visual artist, she writes original poetry in English and in Turkish. In 2014 she published her Turkish translation of Ilya Kaminsky’s acclaimed book Dancing in Odessa; her own first collection of experimental short stories in Turkish, Gece Düşüşü (‘Fall.Night.’), was published in 2012. Elif’s collection of poems Universal Mother was recently published by Gloria SMH Press, and she also published a chapbook The Dervish with Wings early 2017. She holds a PhD in Fine Arts from Monash University. www.elifsezen.com Roisin Kelly is an Irish writer who was born in Belfast and raised in Leitrim. After a year as a handweaver on a remote island in Mayo and a Masters in Writing at National University of Ireland, Galway, she now calls Cork City home. Her chapbook Rapture (Southword Editions in 2016) was reviewed by The Irish Times as ‘fresh, sensuous and direct,’ while Poetry Ireland Review described her as ‘unafraid of sentiment…a master of endings.’ Publications in which her poetry has appeared include POETRY, The Stinging Fly, Lighthouse, and Winter Papers Volume 3 (ed. Kevin Barry and Olivia Goldsmith). In 2017 she won the Fish Poetry Prize. www.roisinkelly.com

Roisin Kelly is an Irish writer who was born in Belfast and raised in Leitrim. After a year as a handweaver on a remote island in Mayo and a Masters in Writing at National University of Ireland, Galway, she now calls Cork City home. Her chapbook Rapture (Southword Editions in 2016) was reviewed by The Irish Times as ‘fresh, sensuous and direct,’ while Poetry Ireland Review described her as ‘unafraid of sentiment…a master of endings.’ Publications in which her poetry has appeared include POETRY, The Stinging Fly, Lighthouse, and Winter Papers Volume 3 (ed. Kevin Barry and Olivia Goldsmith). In 2017 she won the Fish Poetry Prize. www.roisinkelly.com Heather Taylor Johnson’s recent publications are Meanwhile, the Oak (

Heather Taylor Johnson’s recent publications are Meanwhile, the Oak ( Can You Tolerate This

Can You Tolerate This

Cecily Niumeitolu is a PhD candidate researching Beckett’s archives at present. She has had three excursions in Philament, her writing has appeared in Voiceworks, Eclectica, Australian Reader, and she received the Henry Lawson Prize for Prose.

Cecily Niumeitolu is a PhD candidate researching Beckett’s archives at present. She has had three excursions in Philament, her writing has appeared in Voiceworks, Eclectica, Australian Reader, and she received the Henry Lawson Prize for Prose. Cameron Morse taught and studied in China. Diagnosed with Glioblastoma in 2014, he is currently a third-year MFA candidate at the University of Missouri—Kansas City and lives with his wife Lili and newborn son Theodore in Blue Springs, Missouri. His poems have been or will be published in New Letters, Bridge Eight, South Dakota Review, I-70 Review and TYPO. His first collection, Fall Risk, is forthcoming in 2018 from Glass Lyre Press.

Cameron Morse taught and studied in China. Diagnosed with Glioblastoma in 2014, he is currently a third-year MFA candidate at the University of Missouri—Kansas City and lives with his wife Lili and newborn son Theodore in Blue Springs, Missouri. His poems have been or will be published in New Letters, Bridge Eight, South Dakota Review, I-70 Review and TYPO. His first collection, Fall Risk, is forthcoming in 2018 from Glass Lyre Press. Rebecca Vedavathy is a research scholar studying Francophone Literature in EFLU, Hyderabad. She began writing as a child but only discovered its appreciation when she read a Francophone Literature class many years later. She won the Prakriti Poetry Contest, 2016. She longlisted in English Poetry for the Toto Funds the Arts Awards, 2017 and 2018. She is currently a Shastri Indo-Canadian Research Fellow interning at the University of Quebec, Montreal.

Rebecca Vedavathy is a research scholar studying Francophone Literature in EFLU, Hyderabad. She began writing as a child but only discovered its appreciation when she read a Francophone Literature class many years later. She won the Prakriti Poetry Contest, 2016. She longlisted in English Poetry for the Toto Funds the Arts Awards, 2017 and 2018. She is currently a Shastri Indo-Canadian Research Fellow interning at the University of Quebec, Montreal. Luke Best is from Toowoomba on the Darling Downs where he was born in 1982. He is married with three children. He has been published in Overland and his manuscript Percussion was Highly Commended in the 2017 Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize.

Luke Best is from Toowoomba on the Darling Downs where he was born in 1982. He is married with three children. He has been published in Overland and his manuscript Percussion was Highly Commended in the 2017 Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize. Rose Lucas is a Melbourne poet. Her first collection, Even in the Dark (University of WA Publishing), won the Mary Gilmore Award in 2014; her second collection was Unexpected Clearing (UWAP, 2016). She is currently working on her next collection At the Point of Seeing. She is a Senior Lecturer in the Graduate Research Centre at Victoria University.

Rose Lucas is a Melbourne poet. Her first collection, Even in the Dark (University of WA Publishing), won the Mary Gilmore Award in 2014; her second collection was Unexpected Clearing (UWAP, 2016). She is currently working on her next collection At the Point of Seeing. She is a Senior Lecturer in the Graduate Research Centre at Victoria University. Rafeif Ismail’s current work aims to explore the themes of home, belonging and Australian identity in the 21st century. A third culture youth of the Sudanese diaspora, her goal is to create works that

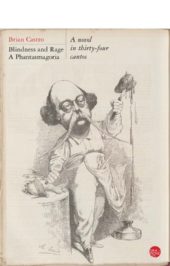

Rafeif Ismail’s current work aims to explore the themes of home, belonging and Australian identity in the 21st century. A third culture youth of the Sudanese diaspora, her goal is to create works that  Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria

Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark

Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark Susan Hurley is a health economist and writer. Her research has been published in numerous international journals including The Lancet and her articles and essays have appeared in Kill Your Darlings,The Big Issue, The Australian and Great Walks. Susan is currently working on a novel that originates from a disastrous drug trial. She lives in Melbourne with her husband and labradoodle. The Death of an Impala was shortlisted for the 2017 Peter Carey Short Story Prize.

Susan Hurley is a health economist and writer. Her research has been published in numerous international journals including The Lancet and her articles and essays have appeared in Kill Your Darlings,The Big Issue, The Australian and Great Walks. Susan is currently working on a novel that originates from a disastrous drug trial. She lives in Melbourne with her husband and labradoodle. The Death of an Impala was shortlisted for the 2017 Peter Carey Short Story Prize. Maris Depers is a Psychologist from Wollongong, NSW. His poetry and short stories have appeared in Kindling III and One Page Literary Magazine.

Maris Depers is a Psychologist from Wollongong, NSW. His poetry and short stories have appeared in Kindling III and One Page Literary Magazine. The Circle and the Equator

The Circle and the Equator Kathy Sharpe is a graduate of the University of Wollongong’s Master of Arts in Creative Writing. She

Kathy Sharpe is a graduate of the University of Wollongong’s Master of Arts in Creative Writing. She Georgia Manuela Delgado is a writer currently based in Sydney with a Portuguese mother. She recently graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from The University of Sydney.

Georgia Manuela Delgado is a writer currently based in Sydney with a Portuguese mother. She recently graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from The University of Sydney. Sentences from the Archive

Sentences from the Archive Sivashneel Sanjappa is a writer, chef and keen gardener originally from Fiji and currently based in Melbourne. He is currently working on his first novel. His work has been published previously in

Sivashneel Sanjappa is a writer, chef and keen gardener originally from Fiji and currently based in Melbourne. He is currently working on his first novel. His work has been published previously in  Jessie Tu’s poems and scripts have appeared in the Australian Book Review, FishFood Magazine and The Voices Project. Winner of 2016 Joseph Furphy Literary Prize in Poetry, she was shortlisted for the Peter Porter Poetry Prize in 2017. She is recently returned from a workshop in creative non-fiction writing at the Iowa Summer Writer’s Festival, University of Iowa. ‘Another Country’, an extract from her memoir-in-progress was shortlisted for the Deborah Cass Prize in 2017, judged by Alice Pung. Her poetry chapbook, You should have told me we have nothing left is forthcoming with Vagabond deciBels 3.

Jessie Tu’s poems and scripts have appeared in the Australian Book Review, FishFood Magazine and The Voices Project. Winner of 2016 Joseph Furphy Literary Prize in Poetry, she was shortlisted for the Peter Porter Poetry Prize in 2017. She is recently returned from a workshop in creative non-fiction writing at the Iowa Summer Writer’s Festival, University of Iowa. ‘Another Country’, an extract from her memoir-in-progress was shortlisted for the Deborah Cass Prize in 2017, judged by Alice Pung. Her poetry chapbook, You should have told me we have nothing left is forthcoming with Vagabond deciBels 3. A Personal History of Vision

A Personal History of Vision False Nostalgia

False Nostalgia Knocks

Knocks Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórquez & Alí Calderón

Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórquez & Alí Calderón Claire Potter ’s most recent poetry publications have appeared in The Fremantle Press Anthology of Western Australian Poetry (edited by John Kinsella and Tracy Ryan), Best Australian Poems 2016 (ed. Sarah Holland-Batt), Poetry Chicago (ed. Robert Adamson), and Poetry Review Ireland. She was shortlisted for a 2017 Keats-Shelley Poetry Prize UK and she has published three poetry collections, In Front of a Comma (Poets Union 2006), N’ombre (Vagabond 2007) and Swallow (Five Islands 2010). She lives in London.

Claire Potter ’s most recent poetry publications have appeared in The Fremantle Press Anthology of Western Australian Poetry (edited by John Kinsella and Tracy Ryan), Best Australian Poems 2016 (ed. Sarah Holland-Batt), Poetry Chicago (ed. Robert Adamson), and Poetry Review Ireland. She was shortlisted for a 2017 Keats-Shelley Poetry Prize UK and she has published three poetry collections, In Front of a Comma (Poets Union 2006), N’ombre (Vagabond 2007) and Swallow (Five Islands 2010). She lives in London. Preparations for Departure

Preparations for Departure Mark O’Flynn’s most recent collection of poems is Shared Breath, (Hope Street Press, 2017). He has published a collection of short stories as well as four novels. His latest The Last Days of Ava Langdon (UQP, 2016) has been shortlisted for the 2017 Miles Franklin Award.

Mark O’Flynn’s most recent collection of poems is Shared Breath, (Hope Street Press, 2017). He has published a collection of short stories as well as four novels. His latest The Last Days of Ava Langdon (UQP, 2016) has been shortlisted for the 2017 Miles Franklin Award. Robbie Coburn was born in Melbourne and grew up on his family’s farm in Woodstock, Victoria. His poems have been published in various journals and magazines including Poetry, Cordite, The Canberra Times, Overland and Going Down Swinging, and his poems have been anthologized. His first collection, ‘Rain Season’, was published in 2013 and a second collection titled The Other Flesh is forthcoming. He lives in Melbourne.www.robbiecoburn.com.au

Robbie Coburn was born in Melbourne and grew up on his family’s farm in Woodstock, Victoria. His poems have been published in various journals and magazines including Poetry, Cordite, The Canberra Times, Overland and Going Down Swinging, and his poems have been anthologized. His first collection, ‘Rain Season’, was published in 2013 and a second collection titled The Other Flesh is forthcoming. He lives in Melbourne.www.robbiecoburn.com.au Constitution

Constitution Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body

Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body Kate

Kate Adam Day is the author of the collection of poetry,

Adam Day is the author of the collection of poetry,  A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work

A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work  Lindsay Tuggle has been widely published in journals and anthologies, including: Cordite, Contrapasso, HEAT, Mascara, Rabbit, and The Hunter Anthology of Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry(2016). She was short-listed for the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s International Poetry Prize, judged by Simon Armitage. Her work has been recognised by major literary awards, including: the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2015), the Val Vallis Award for Poetry (second prize 2009, third prize 2014), and the Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2016, longlisted 2014). Her first collection, Calenture, is forthcoming with Cordite Publishing. The manuscript evolved from residential writing fellowships awarded by institutions including the Australian Academy of the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and the Mütter Museum of Philadelphia. Tuggle also writes on intersections of poetry and science. The University of Iowa Press’s Whitman Series invited her first book, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America (forthcoming in 2017). She wrote a chapter on ‘Poetry and Medicine’ for Cambridge University Press’sWhitman in Context (2017). She teaches literary studies at Western Sydney University.

Lindsay Tuggle has been widely published in journals and anthologies, including: Cordite, Contrapasso, HEAT, Mascara, Rabbit, and The Hunter Anthology of Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry(2016). She was short-listed for the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s International Poetry Prize, judged by Simon Armitage. Her work has been recognised by major literary awards, including: the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2015), the Val Vallis Award for Poetry (second prize 2009, third prize 2014), and the Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2016, longlisted 2014). Her first collection, Calenture, is forthcoming with Cordite Publishing. The manuscript evolved from residential writing fellowships awarded by institutions including the Australian Academy of the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and the Mütter Museum of Philadelphia. Tuggle also writes on intersections of poetry and science. The University of Iowa Press’s Whitman Series invited her first book, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America (forthcoming in 2017). She wrote a chapter on ‘Poetry and Medicine’ for Cambridge University Press’sWhitman in Context (2017). She teaches literary studies at Western Sydney University. Adolfo Aranjuez is editor of Metro, subeditor of Screen Education, and a freelance writer, speaker and dancer. He has edited for Voiceworks and Melbourne Books, and been published in Right Now, The Lifted Brow, The Manila Review, Eureka Street and Peril, among others. Adolfo is one of the Melbourne Writers Festival’s 30 Under 30. http://www.adolfoaranjuez.com

Adolfo Aranjuez is editor of Metro, subeditor of Screen Education, and a freelance writer, speaker and dancer. He has edited for Voiceworks and Melbourne Books, and been published in Right Now, The Lifted Brow, The Manila Review, Eureka Street and Peril, among others. Adolfo is one of the Melbourne Writers Festival’s 30 Under 30. http://www.adolfoaranjuez.com Writing to the Wire

Writing to the Wire Shastra Deo was born in Fiji, raised in Melbourne, and lives in Brisbane. She holds a Bachelor of Creative Arts in Writing and English Literature, First Class Honours and a University Medal in Creative Writing, and a Master of Arts in Writing, Editing and Publishing from The University of Queensland. Her work has appeared in Cordite, Peril, Uneven Floor, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of the 2016 Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize; her debut collection, The Agonist, is forthcoming from UQP in September 2017.

Shastra Deo was born in Fiji, raised in Melbourne, and lives in Brisbane. She holds a Bachelor of Creative Arts in Writing and English Literature, First Class Honours and a University Medal in Creative Writing, and a Master of Arts in Writing, Editing and Publishing from The University of Queensland. Her work has appeared in Cordite, Peril, Uneven Floor, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of the 2016 Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize; her debut collection, The Agonist, is forthcoming from UQP in September 2017. Mindy Gill completed her Honours in Creative Writing at QUT. She has won the Tom Collins Poetry Prize, a Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Voiceworks, Tincture, Hecate, Australian Poetry Journal, and Island Magazine. She is an editor at Peril Magazine.

Mindy Gill completed her Honours in Creative Writing at QUT. She has won the Tom Collins Poetry Prize, a Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Voiceworks, Tincture, Hecate, Australian Poetry Journal, and Island Magazine. She is an editor at Peril Magazine. Laura McPhee-Browne is a writer and social worker from Melbourne, Australia. She is currently working on what she hopes will be her first book, ‘Cooee’, a collection of echo stories inspired by the short fiction of her favourite female writers.

Laura McPhee-Browne is a writer and social worker from Melbourne, Australia. She is currently working on what she hopes will be her first book, ‘Cooee’, a collection of echo stories inspired by the short fiction of her favourite female writers. Paul Dawson’s first book of poems, Imagining Winter (IP, 2006), won the IP Picks Best Poetry Award in 2006, and his work has been anthologized in Contemporary Asian Australian Poets (Puncher & Wattmann, 2013), Harbour City Poems: Sydney in Verse 1888-2008 (Puncher & Wattmann, 2009), and the Newcastle Poetry Prize Anthology, 2016 (Hunter Writers Centre, 2016). Paul teaches in the School of the Arts and Media at the University of New South Wales.

Paul Dawson’s first book of poems, Imagining Winter (IP, 2006), won the IP Picks Best Poetry Award in 2006, and his work has been anthologized in Contemporary Asian Australian Poets (Puncher & Wattmann, 2013), Harbour City Poems: Sydney in Verse 1888-2008 (Puncher & Wattmann, 2009), and the Newcastle Poetry Prize Anthology, 2016 (Hunter Writers Centre, 2016). Paul teaches in the School of the Arts and Media at the University of New South Wales. Annie Blake is an Australian writer who started school without knowing any English. She has been published in Verity La, Vine Leaves Literary Journal, About Place, Australian Poetry Journal and Cordite Poetry Review, forthcoming in Southerly and GFT Press. Her poem ‘These Grey Streets’ has been nominated for the 2017 Pushcart Prize. She is excited about the process of individuation, research in psychoanalysis, philosophy and cosmology. She is a former teacher who lives in Melbourne with her family. She blogs at annieblakethegatherer.blogspot.com

Annie Blake is an Australian writer who started school without knowing any English. She has been published in Verity La, Vine Leaves Literary Journal, About Place, Australian Poetry Journal and Cordite Poetry Review, forthcoming in Southerly and GFT Press. Her poem ‘These Grey Streets’ has been nominated for the 2017 Pushcart Prize. She is excited about the process of individuation, research in psychoanalysis, philosophy and cosmology. She is a former teacher who lives in Melbourne with her family. She blogs at annieblakethegatherer.blogspot.com Jessica Dionne lives in North Carolina and is currently pursuing an MA in Literature from The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She recently presented poems at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association annual conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and her work has been featured in The Longleaf Pine, Luna Luna Magazine, and Pour Vida Zine, and is forthcoming in The Mayo Review, and Rust + Moth.

Jessica Dionne lives in North Carolina and is currently pursuing an MA in Literature from The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She recently presented poems at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association annual conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and her work has been featured in The Longleaf Pine, Luna Luna Magazine, and Pour Vida Zine, and is forthcoming in The Mayo Review, and Rust + Moth. Exhibits of the Sun

Exhibits of the Sun We Need New Names

We Need New Names CB Mako is a member of West Writers Group and art student at Footscray Community Arts Centre.

CB Mako is a member of West Writers Group and art student at Footscray Community Arts Centre.

Fragments

Fragments Annihilation of Caste

Annihilation of Caste Hasti Abbasi holds a BA and an MA in English Literature. She recently submitted her PhD thesis on Dislocation and Remaking Identity in Australian and Persian Contemporary Fictions. Her work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Antipodes, Southerly, Verity La, AAWP, and Bareknuckle Poet Journal of Letters, amongst others.

Hasti Abbasi holds a BA and an MA in English Literature. She recently submitted her PhD thesis on Dislocation and Remaking Identity in Australian and Persian Contemporary Fictions. Her work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Antipodes, Southerly, Verity La, AAWP, and Bareknuckle Poet Journal of Letters, amongst others. Jenna Cardinale writes poems. Some of them appear in Verse Daily, Pith, The Fem, and H_NGM_N. Her latest chapbook, A California, will be published by Dancing Girl Press in 2017. She lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Jenna Cardinale writes poems. Some of them appear in Verse Daily, Pith, The Fem, and H_NGM_N. Her latest chapbook, A California, will be published by Dancing Girl Press in 2017. She lives in Brooklyn, NY. Darlene Silva Soberano is a young Filipino poet who immigrated to Australia at an early age. She is currently completing a Bachelor of Arts at Deakin University. This is her first published poem. You can find her on Twitter at @drlnsbrn

Darlene Silva Soberano is a young Filipino poet who immigrated to Australia at an early age. She is currently completing a Bachelor of Arts at Deakin University. This is her first published poem. You can find her on Twitter at @drlnsbrn R. D. Wood is of Malayalee and Scottish descent and identifies as a person of colour. He has had work published or that is forthcoming from Southerly, Jacket2, Best Australian Poetry, JASAL and Foucault Studies. His most recent collection of poems is Land Fall

R. D. Wood is of Malayalee and Scottish descent and identifies as a person of colour. He has had work published or that is forthcoming from Southerly, Jacket2, Best Australian Poetry, JASAL and Foucault Studies. His most recent collection of poems is Land Fall Roland Leach has three collections of poetry, the latest My Father’s Pigs published by Picaro Press. He is the proprietor of Sunline Press, which has published nineteen collections of poetry by Australian poets. His latest venture is Cuttlefish, a new magazine that includes art, poetry, flash fiction and short fiction.

Roland Leach has three collections of poetry, the latest My Father’s Pigs published by Picaro Press. He is the proprietor of Sunline Press, which has published nineteen collections of poetry by Australian poets. His latest venture is Cuttlefish, a new magazine that includes art, poetry, flash fiction and short fiction.