Michelle Cahill is an Australian novelist and poet of Indian origin. They live in Sydney; their prizes include the the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing, the Kingston Writing School Hilary Mantel International Short Story Prize, the Val Vallis Award and the Red Room Poetry Fellowship. Their work appears in Future Library, ed Anjum Hassan & Sampurna Chatterjee, (Red Hen Press, 2022) and forthcoming in 4A Papers. Daisy & Woolf is published by Hachette.

Michelle Cahill is an Australian novelist and poet of Indian origin. They live in Sydney; their prizes include the the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing, the Kingston Writing School Hilary Mantel International Short Story Prize, the Val Vallis Award and the Red Room Poetry Fellowship. Their work appears in Future Library, ed Anjum Hassan & Sampurna Chatterjee, (Red Hen Press, 2022) and forthcoming in 4A Papers. Daisy & Woolf is published by Hachette.

This interview was recorded on 6 May 2022 on Woi Wurrung Country, on unceded Aboriginal land.

Photo: Nicola Bailey

A.M: I just wanted to start by acknowledging that I live and work and reside on the lands of the Jaggera and Turrbal people, and acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded, before we started.

M.C: Thank you Alicia, I’m currently on Woi Wurrung country, and I’d like to thank the Aboriginal owners. I’d also like to acknowledge the Aboriginal peoples of Guringai country, where I live, their elders past, present, and emerging, and thank them for their laws, their languages and their care of the land, for allowing me to live here on their lands. And to acknowledge that this is stolen land, and always will be Aboriginal land.

A.M: Absolutely. I have recently been studying Alexis Wright’s Boisbouvier oration from the 2018 Melbourne Writer’s Festival, and she has this beautiful quote: “We either ignoring or describing, exploring or grappling on the contested ground of stolen land with unsettled matters”. And I was reading a quote from you, where you talked about your poetry embodying “scrutiny over invasion”. How would you say Daisy & Woolf sits with those unsettled matters?

M.C: I think that it speaks of the story of a group of people who have been disenfranchised from their own country because of colonisation. The history of Anglo-Indians and Eurasian people is such a troubled one, with so much erasure, and has much in common, in many ways, with the history of Aboriginal people being moved, displaced and deracinated, and having to fight back against that to reclaim their language, their sovereignty and their culture. I think one review described this as a “novel of reclaiming” and that’s what I’m bringing into light is Daisy’s culture and Daisy’s language and her – well, not so much her language, I take that part back, but Daisy’s culture and her family and her absence of language, the fact that she resides in English as a result of colonisation. That’s mentioned in the first chapter where she speaks, when she talks about her children being tutored in Urdu and Bengali but they speak English better. There are little pointers in that first introduction to Daisy, where the conflicts for her as a mixed ancestry person are being dramatized by the fiction. So, I think in answer to your question, that’s really how it sits with unsettlement- I also think Mina, being the Australian author, who is also a migrant, an Anglo-Indian migrant, she’s able to sense, always, that she’s on stolen land and that this is Aboriginal land and this comes up for her in the first chapter when she’s talking about how colonisation came to the south coast of New South Wales where her family live, and how there were [coolies] from Bengal on those early ship journeys, and that they actually found their way with some of the colonisers because of Aboriginal people helping them walk from the south coast right up to Sydney, what was Sydney then, in Gadigal country. Mina’s aware of that and she’s also aware in the final chapter which was set in Varuna, not wanting to give too much away, on Gundungurra country where she’s aware, while speaking back to a white male who’s quite entitled. Mina tells him this isn’t even your land anyway, so I feel like Mina is a character who is aware of this fight against racism and this struggle of all disenfranchised people and First Nations people. In her own way, she’s so distanced from her culture, and she carries that grief with her every single day. There are obviously differences between her situation and how it might feel for Aboriginal people, but there are also some similarities and the sense of being able to share that struggle against the colony and against the oppression, which is often Eurocentric oppression and European oppression of First peoples.

A.M: I really liked how the story was cushioned on both sides by an acknowledgement of that, with the parts in the front and the parts in the back that you mentioned. Those were some of the first things that I highlighted that really struck me as poignant, especially with this sort of literature, writing back to the empire, these post-colonial excavations of literary canon, acknowledging that what’s there isn’t just what was always there; that there is so much more that’s been pushed to or resides in the margins, that isn’t spoken about or that stories aren’t recorded from but happened anyway. I thought that was a really beautiful theme throughout the entire text.

M.C: Thank you, Alicia. I love how you described that, as well. It’s a journey towards gathering the knowledge. You have to go back in order to reclaim, to go through the archives and piece together, and also new making as well, creating and adding and contributing to the archives in that process. I guess that was my process as a writer – there are so many gaps when you’ve had this experience as of being disenfranchised from culture and language and home. Having been so dislocated and removed from home, where do you call ‘home’?

In some ways you are always homeless. Those gaps make it very difficult and pose quite a challenge, but I found that on the positive side, there is substantial shared memory and shared collective history that can be added to narrative. I also use technology in terms of the internet to be able to help my research. So that was an enabling aspect to my research, I didn’t always have to go to libraries or rely on books.

A.M: Daisy & Woolf sits with such beautiful peers of texts like Wide Sargasso Sea, or Foe by Coetzee, doing the work of writing back to the empire and centring characters who were, to quote yourself, “devoured in the imperial closet” by the “wolves” of the Western canon. So it has such fine company, as well.

M.C: Thank you, Alicia. I’ve read those novelists and just admire so much the passion and the viscerality of their work, that it is multi-textured and vivid. I wanted to create that sort of narrative detail in Daisy’s journey, in her life and her voice, to give her an embodied voice. I was on residency at the Hurst in Wales at the time, and I was reading lots of journals from travellers who had travelled from India, or had travelled through the Suez Canal, and reading about the Indian independence struggle and so forth. When her voice finally came to me, it was just a wonderful moment that I could start that first chapter, where she speaks of stepping out into the dark morning, it was before dawn, and she was stepping out into the streets of Kolkata. I wanted that her appearance be similar to Clarissa Dalloway’s first appearance in Mrs Dalloway, where Virginia Woolf makes her opening sentence, “Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself”, and on it goes. I wanted something memorable and focused for Daisy, this woman who had an intention to do something that day, whilst conversing with her lover.

A.M: I really enjoyed finding the parallels between the beginning of Mrs Dalloway and the beginning of Daisy & Woolf, but when you departed from that, with Mrs Dalloway being a day in the life of Clarissa, but Daisy & Woolf is so much more, for Daisy and for Mina, it spans so much more time and space, and I really liked how you made that distinction.

M.C: I didn’t attempt to do anything in particular in terms of comparing the work to Mrs Dalloway, I was more focussed on the voice, getting the voice right, and then allowing the voice to follow its own journey. I had a good sense of where Daisy was going, so that helped me to structure the novel, because I knew she was traveling to England. Still, I didn’t really know what was going to happen. It’s a beautiful thing to have the story lead you as a writer and you trust that, as well as being the engineer of it. To allow that trust, I think it’s an interwoven relationship that you have with the text itself.

A.M: I love how Daisy has the agency, even in the structure and writing of her own story, I’m very fond of that idea, of characters having their own agency, if we’re just the scripters, I guess? That’s very interesting.

M.C: I experimented with the use of diary and letters. I thought a fair bit about whether to write in first person present or past tense or third person, as well, and I think a lot of my work I try in different tenses, POV as well and see how that works. The immediacy of the first person is powerful, it becomes quite separate from me as a writer. Even with Mina’s voice, although there are definitely autobiographical traces to it, having a first person POV, Mina becomes her own self and is released from me.

A.M: I really enjoyed how different and distinct the voice of Mina and Daisy were throughout the text. I very much enjoyed that, even though as a metafiction we understand the motions of writing but seeing the distinct voices and how they would tackle things was very interesting.

M.C: Mm, so how did you find the difference between Mina and Daisy’s voice in that respect?

A.M: I found they were both, not bleak so to speak but there was definitely an element of bleakness to the writing, in both perspectives. I think Mina’s was almost more visceral because there was more… not that there was more emotion, but there was more immediacy, because it was dated to 2017, and contextualised by events that she was mentioning, like the Grenfell tower collapse, and a lot of things that contemporary readers would see and remember. With Daisy, though, it was slightly different, but they both had elements of bleakness and viscerality, as you say, I totally agree.

M.C: Grenfell Tower and all the events that were happening, it is something that we find ourselves watching on social media, and all these things happening, the Black Lives Matter movement, landslides and environmental issues affecting Nepal and the Himalayan areas, all the changes that are happening, and we know that people of colour are suffering, right? They’re the ones who are going to be impacted, the ones who have housing insecurity, who are affected most in these situations, with economic vulnerability. There’s a sense of this world that we’re living in being so problematic on so many levels. Mina is also dealing with personal issues and past traumas, losses of her relationship with her offspring and the loss of her mother, her grief, and she’s trying to navigate personal intimacy as well. It’s a very fraught time for her that the novel is charting.

A.M: Both perspectives are saturated with grief, but especially with the modern events – I think because of social media, we have such an immediacy of knowledge, things pop up on Twitter or Instagram, we see them, we scroll. We think about it for a couple of days, or a couple of weeks, but then the next big, horrible event happens, and we’re distracted by it. But when we see those events harkened back to in fiction, it brings back all the emotions that were inherent to it, that we forgot about because of how readily information is available.

M.C: Absolutely, that is so true. How we just move on, it’s sort of overwhelming: a cascading current of issues and concerns; and so often re-traumatising.

A.M: There’s so much to pay attention to, so much to give nuanced thought to, but there isn’t a lot of time, because things are always happening.

M.C: It fragments us, doesn’t it?

A.M: Yes, absolutely.

M.C: It’s very hard to then focus on the work we have, the task of writing, which Mina has undertaken. In order to do that, to excavate that space, she has to sacrifice quite a fair bit. That’s where the bleakness comes through, the waves of bleakness and vulnerability.

A.M: Carving time for the people and the characters that haunt us, even though there’s already so much haunting us from contemporary events.

M.C: The haunting of Daisy’s voice through her life. And Shuhua Ling, the Chinese author who was in a relationship with Virginia Woolf’s nephew, she is also ghosting Mina’s writing of this novel.

A.M: Yes, this text is full of ghosts. But I like that we’re giving them, not so much a space to haunt but shining a light on them so they can tell their own stories, rather than just echoes through the text or other people’s works. I thought that was wonderful.

M.C: Ah, right. And how do you think it’s different in non-fiction? Does fiction do something different for you, reading these stories about these women, Shuhua Ling and Daisy – was that a different experience than say, if you had read about it in an essay, I’m curious about that.

A.M: I think so. It makes me think a lot about literary language and how that has such a different effect even if the words are the same, or have cousins in non-fiction, so to speak. I think the emotional aspect of literary language and fiction holds hands with the ghosts of these women. It’s much easier to read and see their experiences through literary language. It reminds me a little of Bakhtin, how he talks about literary language, specifically the language of novels is heteroglossic and it contains multiple different languages within the text – the languages of class difference, or race, or gender – and I think that is what’s happening here, in the literary language of Daisy & Woolf. I wouldn’t, I don’t think, get the same experience with non-fiction – I don’t the ghosts would be quite so loud, or prominent.

M.C: What Bakhtin says about heteroglossia and how literary language allows these interactions of different registers of voices. The silences become vocalised in all their different registers; I agree. In an essay, a writer can be scrutinised, and it’s so factually dependent, that your interpretation of facts in an essay could be criticised or turned around and used against the purpose that you had hoped to champion. I feel that in fiction, that’s less of the case because you don’t need to rely necessarily on the facts, although you can use fact, but you can use elements of the surreal, elements of embellishment or dream, or poetic language, or have different visualisations coming into the facts and merging with facts. In that respect, there’s a license for you to explore, and speak with greater liberty, to allow these aspects to be fleshed out. You’re doing that from behind a shield that protects not so much yourself but protects the truth that you want to give a space for as a creator and as a writer. I don’t like the word creator [laughs], I feel like it’s quite a dominating way of thinking about the writing process.

A.M: Hmm, is there a term you prefer?

M.C: I think ‘writer’, I don’t mind ‘writer’, but I find it’s a little bit precious, in a way, and I’m a little bit anxious about it, for myself anyway, I like to trust the work a lot and to build my intuition and work with that. I like to allow that to take on a life. Though, in some respects, it’s out of my control.

A.M: Yeah, it’s sort of as if the term ‘writer’ has a sense of something along the lines of ownership? Giving the text the agency to be what it wants be, the purpose that you wanted it to have, but also have its own sovereignty.

M.C: Absolutely. It’s such an interesting process, and it’s also interesting to talk about it, as well, because it’s a curious thing to talk about, that text that is quite separate from you, to talk about it objectively. Maybe that’s a tricky thing, in some ways. But I think what I’m really excited about is that it’s a story I hope will take on it’s own life. The most exciting thing for me, to be quite honest, is when people are reading it, for it to have its own life in their imagination, not in mine. In that respect, it isn’t my story anymore.

A.M: Absolutely. Perhaps not as concrete as death of the author, but letting it transform from not just a work but a text.

M.C: That’s right. I just have this little bit of confidence that it has a vividness, that it will come alive in people’s imaginations: the voices of these women, these brown women. It’s so exciting for me to see the term ‘Anglo-Indian’ used and being discussed in forums.

A.M: Well, it’s definitely taken a life in my own imagination, and I have been pestered quite a few of my friends about it, saying “you have to read it, you have to”, and using my bookseller privileges for evil [both laugh].

M.C: Oh, awesome, that is so good to hear.

A.M: So I can tell you for me it’s definitely taken a life in my head, and when I was reading it, there were so many times I put the book down to go “okay, that was a sentence I just read. I have to turn that around in my brain now” [laughs]. I’ve tabbed the life out of this poor book!

M.C: [laughs] I saw that lovely photo that you posted with the little tabs, that was amazing, that was so lovely. I’m really glad that you enjoyed it, I really enjoy hearing that people loved the characters or that they found it very vivid, that means a lot. There’s a lot of different aspects to the industry, but that’s a very special part of it, to hear readers responding in that way. To me, anyway, I don’t mean to be anyone else, I know there’s a clichéd persona of the ‘writer’ [laughs]. I’m just myself, just following my truths and pursuing and putting it out there and believing in it, being willing to say these things. For example, about storytelling, about how I like most when the story writes itself, it’s out of my control. There were parts when Daisy is in France, and some of the things that strike her were not planned, it was just my fingers tapping on the keyboard and these sentences coming out. They were deep feelings she was having about the losses she’d experienced as a brown woman leaving her home in Kolkata. I won’t say too much because I’d like readers to follow the story themselves but, yeah, it was really wonderful that it was just Daisy channelling through me. I do love that most about fiction, and poetry as well, but particularly in fiction, when that’s happening, you really trust the truth of it.

A.M: That’s such an endearing idea, that characters are just writing through us. You take a step back as a writer and ask them “where do you want to go, where does your story go next?” That’s such a brilliant idea, I really enjoy that concept, especially with work like this, and I think that’s how we get monumental works like Daisy & Woolf and like Wide Sargasso Sea and their peers, when characters really say “no, this is my story, and this is how it’s going to go.”

M.C: Oh, awesome. Talking to you, telling you, instructing you, taking on life and a body and language. I suppose it’s like the way we talk to plants, and plants talk to us. It’s that kind of thing, where there are these voices we can connect with and hear and respond to and channel.

A.M: Absolutely. We were just talking about the industry before, and I wanted to know, are there any pieces of wisdom or advice you would like to pass down to other writers, whether they’re new writers or young writers or any sort of writer? Or, is there anything you wish that someone would’ve told you about writing or the industry, not just before this book but before your other poetry pieces or essays?

M.C: I would definitely say persistence is important for writing. The most necessary thing is to believe in yourself and to believe in your work, and to trust that passion and believe in it. To not be swayed by society’s pressures about what you should be doing with your life. Be obsessed. Be okay with the obsession that writing is, keep finding your strengths and improving your weaknesses, where you see faults in your writing. In some ways I think, although it’s wonderful to have readers who go over your work and give you feedback, you are your best teacher. Finding what’s not working and what is working – you’ll do that by just doing the writing, the more you practice. I think there’s something technical about writing, as well, in that respect. The more you do, the better you become. You just get to be at the point where it happens, but it’s happening more easily. You also need to give yourself the space, to create spaces for yourself, and time and place and opportunities for you to immerse. Never be discouraged, because it is a long journey, but it’s so worthwhile. Even though you may have failures, in the short-term, in front of you, that’s just nothing in the scheme of time. Ahead of you are these successful pieces of work, they’re there, take your time. There’s no rush. Sometimes we feel that pressure, so-and-so’s got a novel out and they’re twenty-five, and they’ve got an agent, but there’s actually so much time. So, stay calm with that. Trust the real process and spend time with your writing, that’s my advice.

A.M: That’s so wonderful to hear, thank you very much for that! There is definitely that pressure, there are so many amazing young, successful authors, but there is always that feeling of “oh, they released their book at twenty-one and I’m twenty, when am I going to”, sort of thing. So, it is so nice to hear reaffirmed that there is that allowance of time.

M.C: Absolutely, there is so much time, and it is so worthwhile when you can have a book – I look at this now and I’m so happy and proud, it’s such a good book for myself. Nobody else’s measure, just my own measure, and I’m so proud of it. In some ways, it was a long time coming, in research and upskilling myself, and in other ways. So yeah, there’s that time and there’s time ahead; enjoy the journey, that’s what I say, enjoy. It’s so rich and there’s no rush.

A.M: That’s wonderful, and it is such an amazing novel, you should absolutely be so so proud of it, it is so good.

M.C: Oh, thank you, Alicia. I really appreciate your reading. The other thing I would say to writers is that I think it’s really refreshing to be amongst communities of writers, such as yourself, and younger people. That’s where the energy lies, actually. I was so looking forward to talking to you, I could just tell from your review you loved the book and your questions would be refreshing. It’s so important to not worry too much about the conventional and the heavy critics, don’t bother so much about reviews. Just connect with your audience, and with your communities, young communities, diverse communities, LGBTIQ+ communities, POC communities. It’s so important that we just open up the spaces.

A.M: Absolutely! When we get those voices that have been pushed to the margin, that’s when we get these beautiful, transformative works of art that we wouldn’t have otherwise. It’s terrible that they have to push themselves into the centre because they’ve been denied places, but when we finally start hearing from people who have either been denied the language or the agency or the space to make these pieces of art – the art that we get is just fantastic.

M.C: It is, it’s so rich. One of the things I’ve focused on, in talking about the book, is collaboration and the importance of allyship. The novel does speak to the non-encounter of white feminism with the other woman. That is something that allyship can address, and to me, it’s been an important part of activism. There are many very radical thinkers in Australia who really want to push things forward and change the literary landscape, and to allow for literature to be transformative. I think allyship and collaboration are really crucial, and that’s why, in part, I agreed to change the title from ‘Woolf’ to Daisy & Woolf. My initial title was Woolf, and it was suggested to me to change it and I totally embraced that, because I think book production is not something a single individual person can achieve, it’s a collaborative effort. Together we’re part of an industry that loops, and a collective community, and we all contribute. We can sulk and harden, but we can also vibe together. Through shared work, we can reform and transform.

A.M: Yes, definitely. As you talked a little about the decision to change the title, at first I didn’t quite understand, but when you explain the connection to allyship, it makes sense. The part in the novel, when you talk about the poetics and the etymology of ‘woolf’, and the different variations of that – that was such a fascinating passage, linguistically, and to tie that into the title and allyship is so very interesting.

M.C: Thanks Alicia, I enjoyed writing that part! The title ‘Woolf’, as a metaphor is quite powerful, and that was the title I wanted, however, I feel that metaphor itself is being challenged. It comes from an aesthetic tradition which tends to be apolitical in the way it negotiates meaning and representation. I think that the power of naming Daisy is specific and sets down her difference, exceeding the power of metaphor. Even though owing to my background as a poet, I’m naturally drawn to metaphor, I feel that just the naming of Daisy with Woolf, the appearance of [Daisy] on the cover, an Indian woman, a dark woman, dressed in European clothes with a European haircut. That hybridity centres her, the Eurasian woman beside Woolf, the white feminist, the privileged upper-class colonial. There is a subtle, unique presence.

A.M: There is always a sort of fondness, too, whenever Woolf is mentioned, even while excavating the Orientalism embedded in her work, especially Mrs Dalloway. By placing India and Daisy in the narrative’s peripheral, but there is always that imagining of Woolf. It was a very nuanced perspective and I very much enjoyed that reading as – I don’t want to say ‘as a Woolf fan’, but as a someone who has enjoyed her works – I thought it was a very interesting, very beautiful perspective.

M.C: So, you enjoyed the homage?

A.M: Yes. I definitely did. I wouldn’t say Mrs Dalloway is my favourite, but I did definitely like the connections. With Daisy & Woolf, you can’t forget that there is a homage aspect, but it becomes beautifully its own text. If that was worded well [laughs].

M.C: That was worded perfectly, I’m very happy to hear that you had that response to the text.

A.M: Thank you so much for your time, out of your very busy schedule I’m sure! And thank you for your lovely words on my review of Daisy & Woolf.

M.C: Thank you, that’s awesome. I’ve loved chatting with you, we’ve covered some great ground and topics, I’ve really enjoyed hearing your reflections.

A.M: Thank you so much!

ALICIA MARSDEN is an Australian reviewer, bookseller and student. She studies law, literature and politics at the University of Queensland, and is passionate about the overlap between legal studies and literature, namely the gothic. She blogs about books and her current literary musings on Instagram, @dashedwithprose.

ALICIA MARSDEN is an Australian reviewer, bookseller and student. She studies law, literature and politics at the University of Queensland, and is passionate about the overlap between legal studies and literature, namely the gothic. She blogs about books and her current literary musings on Instagram, @dashedwithprose.

Liel (she/they) is a writer, trainer, Psychologist (Provisional) and a disability and justice advocate based in Naarm. Her work is published in ABC Arts, MamaMia, the anthology We’ve Got This published by Black Inc. and Scribe UK, and Hireup, amongst others. Liel was the 2022 editor of Writing Place magazine, and is the creator and host of the (Un)marginalised podcast. She not-so-secretly enjoys singing along to the Frozen soundtrack with her kids, and is somewhat fixated on parenting related humour. Find out more about Liel’s work on her website and follow her attempts to keep up with social media via @LielKBridgford.

Liel (she/they) is a writer, trainer, Psychologist (Provisional) and a disability and justice advocate based in Naarm. Her work is published in ABC Arts, MamaMia, the anthology We’ve Got This published by Black Inc. and Scribe UK, and Hireup, amongst others. Liel was the 2022 editor of Writing Place magazine, and is the creator and host of the (Un)marginalised podcast. She not-so-secretly enjoys singing along to the Frozen soundtrack with her kids, and is somewhat fixated on parenting related humour. Find out more about Liel’s work on her website and follow her attempts to keep up with social media via @LielKBridgford. Harvest Lingo

Harvest Lingo Purbasha Roy is a writer from Jharkhand India. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Channel, SUSPECT, Space and Time magazine, Strange Horizons, Acta Victoriana, Pulp Literary Review and elsewhere. She attained second position in 8th Singapore Poetry Contest, and has been a Best of the Net Nominee.

Purbasha Roy is a writer from Jharkhand India. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Channel, SUSPECT, Space and Time magazine, Strange Horizons, Acta Victoriana, Pulp Literary Review and elsewhere. She attained second position in 8th Singapore Poetry Contest, and has been a Best of the Net Nominee. Javeria Hasnain is a Pakistani poet and writer, a Fulbright scholar, and an MFA student at The New School, NY. Her prose and poetry have appeared/is forthcoming in Poet Lore, The Margins, Isele, and elsewhere. She was a runner-up for the 2022 The Bird in Your Hands prize and an honorable mention in the 2022 Penrose Poetry Prize. She currently works at Cave Canem and reads poetry for Alice James Books. She has received support from Tin House Workshops, The Kenyon Review, Sundress, and International Writing Program.

Javeria Hasnain is a Pakistani poet and writer, a Fulbright scholar, and an MFA student at The New School, NY. Her prose and poetry have appeared/is forthcoming in Poet Lore, The Margins, Isele, and elsewhere. She was a runner-up for the 2022 The Bird in Your Hands prize and an honorable mention in the 2022 Penrose Poetry Prize. She currently works at Cave Canem and reads poetry for Alice James Books. She has received support from Tin House Workshops, The Kenyon Review, Sundress, and International Writing Program. I Have Decided To Remain Vertical

I Have Decided To Remain Vertical Mohamed Irba / محمد (he/him/هو) is an Omani Lebanese cis man who came to Australia in 2007 at sixteen to study and stayed for safety. He is an active member of his communities and continues to explore the meaning of belonging in everyday life and the intersections of his identity as a Queer Arab person living with HIV.

Mohamed Irba / محمد (he/him/هو) is an Omani Lebanese cis man who came to Australia in 2007 at sixteen to study and stayed for safety. He is an active member of his communities and continues to explore the meaning of belonging in everyday life and the intersections of his identity as a Queer Arab person living with HIV. Acanthus

Acanthus

Freedom, Only Freedom

Freedom, Only Freedom Kirli Saunders (OAM) is a proud Gunai Woman and award-winning multidisciplinary artist and consultant. An experienced writer, speaker and facilitator advocating for the environment and equality, Kirli creates to connect to make change. She was the NSW Aboriginal Woman of the Year (2020) and was awarded an Order of Australia Medal in 2022 for her contribution to the arts, particularly literature.

Kirli Saunders (OAM) is a proud Gunai Woman and award-winning multidisciplinary artist and consultant. An experienced writer, speaker and facilitator advocating for the environment and equality, Kirli creates to connect to make change. She was the NSW Aboriginal Woman of the Year (2020) and was awarded an Order of Australia Medal in 2022 for her contribution to the arts, particularly literature. Kavita Ivy Nandan was born in New Delhi, grew up in Suva and migrated to Australia in 1987 after the Fiji military coups. She completed a PhD in Literature on the postcolonial narratives of Salman Rushdie and VS Naipaul at the Australian National University. In 2017, she moved from Canberra to Sydney with her husband, Michael and son, Jesse. Kavita teaches Creative Writing at Macquarie University. She is the author of a book of poems, Return to what Remains (Ginninderra Press, 2022) and a novel, Home after Dark (USP Press, 2014). She is also the editor of a book of memoirs, Stolen Worlds: Fiji-Indian Fragments and co-editor of a book of essays, Unfinished Journeys: India File From Canberra and a book of poetry and short fiction, Writing the Pacific. Her poetry and fiction are published in LiteLitOne, Not Very Quiet, Mindfood, Mascara Literary Review, Transnational Literature, Landfall, The Island Review and Asiatic. She has been a recipient of the artsACT grant three times.

Kavita Ivy Nandan was born in New Delhi, grew up in Suva and migrated to Australia in 1987 after the Fiji military coups. She completed a PhD in Literature on the postcolonial narratives of Salman Rushdie and VS Naipaul at the Australian National University. In 2017, she moved from Canberra to Sydney with her husband, Michael and son, Jesse. Kavita teaches Creative Writing at Macquarie University. She is the author of a book of poems, Return to what Remains (Ginninderra Press, 2022) and a novel, Home after Dark (USP Press, 2014). She is also the editor of a book of memoirs, Stolen Worlds: Fiji-Indian Fragments and co-editor of a book of essays, Unfinished Journeys: India File From Canberra and a book of poetry and short fiction, Writing the Pacific. Her poetry and fiction are published in LiteLitOne, Not Very Quiet, Mindfood, Mascara Literary Review, Transnational Literature, Landfall, The Island Review and Asiatic. She has been a recipient of the artsACT grant three times. Naomi Williams writes on Kaurna Country. She enjoys experimenting with poetry and prose. Her poetry has been published in Raining Poetry in Adelaide in 2022 and her ekphrastic prose in FELTspace Writer’s Program 2021. She is a lyric writer and was a creative collaborator with the UNESCO Creative Cities Equaliser Music Video Project in Adelaide 2021. She has recently completed her Honours in Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide. Naomi enjoys performing spoken word at open mics around Adelaide and performing comedy raps as part of the duo Bubble Rap.

Naomi Williams writes on Kaurna Country. She enjoys experimenting with poetry and prose. Her poetry has been published in Raining Poetry in Adelaide in 2022 and her ekphrastic prose in FELTspace Writer’s Program 2021. She is a lyric writer and was a creative collaborator with the UNESCO Creative Cities Equaliser Music Video Project in Adelaide 2021. She has recently completed her Honours in Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide. Naomi enjoys performing spoken word at open mics around Adelaide and performing comedy raps as part of the duo Bubble Rap. Maki Morita (she/they) is a Japanese-Australian writer and performance maker on unceded Wurundjeri country. Recent projects include dance piece (live art, Labour Lexica exhibition, Linden New Art, 2022) and Trash Pop Butterflies, Dance Dance Paradise (fortyfivedownstairs 2022, Theatre Works 2023). She is a 2022 Wheeler Centre Playwright Hot Desk Fellow and has appeared in events including National Young Writers Festival, Feminist Book Week and Yardstick.

Maki Morita (she/they) is a Japanese-Australian writer and performance maker on unceded Wurundjeri country. Recent projects include dance piece (live art, Labour Lexica exhibition, Linden New Art, 2022) and Trash Pop Butterflies, Dance Dance Paradise (fortyfivedownstairs 2022, Theatre Works 2023). She is a 2022 Wheeler Centre Playwright Hot Desk Fellow and has appeared in events including National Young Writers Festival, Feminist Book Week and Yardstick. Anthea Yang is a writer and poet living on unceded Wurundjeri land. Her writing has appeared in Going Down Swinging, Kill Your Darlings, Voiceworks and the HEIDE+Rabbit House of Ideas: Modern Women anthology, among others. She has been longlisted for the 2021 Kuracca Prize for Australian Literature, shortlisted for the 2020 Dorothy Porter Award for Poetry, and has performed her poetry as part of Emerging Writers’ Festival, Melbourne Writers Festival, and Red Room Poetry’s 2022 Victorian Poetry Month Gala. Born in Perth, Western Australia, her favourite season is summer.

Anthea Yang is a writer and poet living on unceded Wurundjeri land. Her writing has appeared in Going Down Swinging, Kill Your Darlings, Voiceworks and the HEIDE+Rabbit House of Ideas: Modern Women anthology, among others. She has been longlisted for the 2021 Kuracca Prize for Australian Literature, shortlisted for the 2020 Dorothy Porter Award for Poetry, and has performed her poetry as part of Emerging Writers’ Festival, Melbourne Writers Festival, and Red Room Poetry’s 2022 Victorian Poetry Month Gala. Born in Perth, Western Australia, her favourite season is summer. Patrick Flanery is the author of four novels, including Absolution (2012), which was shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary award, and a memoir, The Ginger Child. He is Chair of Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide.

Patrick Flanery is the author of four novels, including Absolution (2012), which was shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary award, and a memoir, The Ginger Child. He is Chair of Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide. Timmah Ball is a writer and zine maker of Ballardong Noongar heritage. Previous zines and micro publications include Wild Tongue in collaboration with Loving Feminist Literature for Melbourne Fringe (2016), Wild Tongue Vol. 2 in collaboration with Azja Kulpinska for Next Wave Festival (2018) and Do Planners Dream of Electric Trees? (2021) created through Arts House Makeshift public residency. Her writing has appeared in a range of anthologies and literary magazines including Sydney Review of Books, Meanjin, The Griffith Review and Columbia University’s The Avery Review. In 2016 she won the Westerly Patricia Hackett Prize.

Timmah Ball is a writer and zine maker of Ballardong Noongar heritage. Previous zines and micro publications include Wild Tongue in collaboration with Loving Feminist Literature for Melbourne Fringe (2016), Wild Tongue Vol. 2 in collaboration with Azja Kulpinska for Next Wave Festival (2018) and Do Planners Dream of Electric Trees? (2021) created through Arts House Makeshift public residency. Her writing has appeared in a range of anthologies and literary magazines including Sydney Review of Books, Meanjin, The Griffith Review and Columbia University’s The Avery Review. In 2016 she won the Westerly Patricia Hackett Prize. Alison J Barton is a Wiradjuri poet based in Naarm. Themes of race relations, Aboriginal-Australian history, colonisation, gender and psychoanalytic theory are central to her work. Her work appears in Meanjin, Overland, Best of Australian Poetry 2022 (APJ), the Liquid Amber Prize Anthology: Poetry of Encounter, Australian Poetry Journal, Otoliths, Rabbit, Westerly Mag, StylusLit, Resilience (Ed. Mascara) , The Storms (Ireland), Poethead (Ireland), The Night Heron Barks (USA), Under Bunjil, Yarra Libraries Receipt Poetry, Bluebottle Journal and LinkBund. In 2022 Alison received a commended place in the WB Yeats Poetry Prize for Australia, was shortlisted for both the Queensland Poetry Oodgeroo Noonuccal Poetry Prize (for ‘buried light’) and the Pratik Magazine Fire and Rain edition prize (for ‘How to grieve in the open air’) and longlisted for the inaugural Liquid Amber Press Poetry Prize.

Alison J Barton is a Wiradjuri poet based in Naarm. Themes of race relations, Aboriginal-Australian history, colonisation, gender and psychoanalytic theory are central to her work. Her work appears in Meanjin, Overland, Best of Australian Poetry 2022 (APJ), the Liquid Amber Prize Anthology: Poetry of Encounter, Australian Poetry Journal, Otoliths, Rabbit, Westerly Mag, StylusLit, Resilience (Ed. Mascara) , The Storms (Ireland), Poethead (Ireland), The Night Heron Barks (USA), Under Bunjil, Yarra Libraries Receipt Poetry, Bluebottle Journal and LinkBund. In 2022 Alison received a commended place in the WB Yeats Poetry Prize for Australia, was shortlisted for both the Queensland Poetry Oodgeroo Noonuccal Poetry Prize (for ‘buried light’) and the Pratik Magazine Fire and Rain edition prize (for ‘How to grieve in the open air’) and longlisted for the inaugural Liquid Amber Press Poetry Prize. Kamilaroi author Vivienne Cleven was born in 1968 and grew up in outback Queensland. She left school at thirteen to work with her father as a jillaroo: building fences and mustering sheep and cattle. She also worked as a cleaner, barmaid, roustabout, nanny, and photographer, among other jobs. Her novel Bitin’ Back won the David Unaipon Award and shortlisted in the 2002 Courier-Mail Book of the Year Award and the 2002 South Australian Premier’s Award for Fiction. She wrote the playscript for Bitin’ Back, which was performed by Brisbane’s Kooemba Jdarra Indigenous Theatre Company. Sister’s Eye was published in 2002 and was chosen in the 2003 People’s Choice shortlist of One Book One Brisbane. Her writing is included in Fresh Cuttings, the first anthology of UQP Black Australian Writing, published in 2003.

Kamilaroi author Vivienne Cleven was born in 1968 and grew up in outback Queensland. She left school at thirteen to work with her father as a jillaroo: building fences and mustering sheep and cattle. She also worked as a cleaner, barmaid, roustabout, nanny, and photographer, among other jobs. Her novel Bitin’ Back won the David Unaipon Award and shortlisted in the 2002 Courier-Mail Book of the Year Award and the 2002 South Australian Premier’s Award for Fiction. She wrote the playscript for Bitin’ Back, which was performed by Brisbane’s Kooemba Jdarra Indigenous Theatre Company. Sister’s Eye was published in 2002 and was chosen in the 2003 People’s Choice shortlist of One Book One Brisbane. Her writing is included in Fresh Cuttings, the first anthology of UQP Black Australian Writing, published in 2003. Maria van Neerven is a Mununjali Yugambeh women from south-east Queensland. She is a retired library technician who loves reading and writing poetry. Her first published story was in the journal The Lifted Brow: Blak Brow (2018) and she has also published poetry in In Our Hands, (2022) a collection of poetry from Elders and knowledge keepers. Maria has performed her work on stages across Alice Springs and Brisbane and is working on her first collection.

Maria van Neerven is a Mununjali Yugambeh women from south-east Queensland. She is a retired library technician who loves reading and writing poetry. Her first published story was in the journal The Lifted Brow: Blak Brow (2018) and she has also published poetry in In Our Hands, (2022) a collection of poetry from Elders and knowledge keepers. Maria has performed her work on stages across Alice Springs and Brisbane and is working on her first collection. Childhood

Childhood This Devastating Fever

This Devastating Fever

Anneliz Marie Erese is a Filipino writer whose works have appeared or are forthcoming in The Saturday Paper, Meanjin, Island Online and Cordite Poetry Review, among others. She has previously received writing prizes such as the Nick Joaquin Asia Pacific Literary Awards (2019) and the Deakin Postgraduate Prize in Writing and Literature (2022). She was also the 2022 Deborah Cass Prize winner. Most recently, she was awarded a scholarship to Faber Writing Academy at Allen & Unwin. She lives on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people.

Anneliz Marie Erese is a Filipino writer whose works have appeared or are forthcoming in The Saturday Paper, Meanjin, Island Online and Cordite Poetry Review, among others. She has previously received writing prizes such as the Nick Joaquin Asia Pacific Literary Awards (2019) and the Deakin Postgraduate Prize in Writing and Literature (2022). She was also the 2022 Deborah Cass Prize winner. Most recently, she was awarded a scholarship to Faber Writing Academy at Allen & Unwin. She lives on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people. Gayatri Nair is an Indian-Australian writer, poet and DJ based on the land of the Wangal people of the Eora nation in Sydney’s inner west. She is a member of Sweatshop: Western Sydney Literacy Movement, has qualifications in Law and Arts, and is working in human rights policy, research and advocacy. She is passionate about pride in cultural identity and using art to affect change. Gayatri has been published in Sweatshop Women Volumes 1 and 2, Red Room Poetry, Mascara Literary Review, The Guardian and Swampland Magazine.

Gayatri Nair is an Indian-Australian writer, poet and DJ based on the land of the Wangal people of the Eora nation in Sydney’s inner west. She is a member of Sweatshop: Western Sydney Literacy Movement, has qualifications in Law and Arts, and is working in human rights policy, research and advocacy. She is passionate about pride in cultural identity and using art to affect change. Gayatri has been published in Sweatshop Women Volumes 1 and 2, Red Room Poetry, Mascara Literary Review, The Guardian and Swampland Magazine. Christopher Cyrill is the author of the novels The Ganges and its Tributaries and Hymns for the Drowning. He has also published numerous stories, articles and written a number of broadcasted radio plays. For many years he was the fiction editor of HEAT and the fiction editor of Giramondo Publishing. Cyrill has taught at Sydney University and Macquarie University and currently runs his own writing academy mentoring writers.

Christopher Cyrill is the author of the novels The Ganges and its Tributaries and Hymns for the Drowning. He has also published numerous stories, articles and written a number of broadcasted radio plays. For many years he was the fiction editor of HEAT and the fiction editor of Giramondo Publishing. Cyrill has taught at Sydney University and Macquarie University and currently runs his own writing academy mentoring writers. Vyacheslav Konoval is a Ukrainian poet and resident of Kyiv. His poems have appeared in many magazines, including Anarchy Anthology Archive, International Poetry Anthology, Literary Waves Publishing, Sparks of Kaliopa, Reach of the Song 2022, Diogenes for Culture Journal, Scars of my heart from the war, Poetry for Ukraine, Norwich University research center, Impakter, The Lit, Allegro, Innisfree Poetry Journal, Fulcrum, Adirondack Center for Writing, Lothlorien Poetry Journal, Revista Literaria Taller Igitur, Tarot Poetry Journal, Tiny Seed Literature Journal, Best American Poetry Blog, Appalachian Journal Dark Horse. Vyacheslav’s poems were translated into Spanish, French, Scottish, and Polish languages.

Vyacheslav Konoval is a Ukrainian poet and resident of Kyiv. His poems have appeared in many magazines, including Anarchy Anthology Archive, International Poetry Anthology, Literary Waves Publishing, Sparks of Kaliopa, Reach of the Song 2022, Diogenes for Culture Journal, Scars of my heart from the war, Poetry for Ukraine, Norwich University research center, Impakter, The Lit, Allegro, Innisfree Poetry Journal, Fulcrum, Adirondack Center for Writing, Lothlorien Poetry Journal, Revista Literaria Taller Igitur, Tarot Poetry Journal, Tiny Seed Literature Journal, Best American Poetry Blog, Appalachian Journal Dark Horse. Vyacheslav’s poems were translated into Spanish, French, Scottish, and Polish languages. Lesh Karan is a Naarm/Melbourne-based writer and poet. Her work has been published in Best of Australian Poems 2022, Australian Poetry Journal, Cordite Poetry Review, Island, Mascara Literary Review and Rabbit, amongst others. Lesh is currently completing a Master of Creative Writing, Publishing and Editing at the University of Melbourne. She’s of Fiji Indian heritage.

Lesh Karan is a Naarm/Melbourne-based writer and poet. Her work has been published in Best of Australian Poems 2022, Australian Poetry Journal, Cordite Poetry Review, Island, Mascara Literary Review and Rabbit, amongst others. Lesh is currently completing a Master of Creative Writing, Publishing and Editing at the University of Melbourne. She’s of Fiji Indian heritage. Morgaine Riley is a writer and English tutor from Peramangk Country (the Adelaide Hills). In 2021, she was awarded the Peter Davies Memorial Prize for Creative Writing. She has recently completed an Honours in Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide.

Morgaine Riley is a writer and English tutor from Peramangk Country (the Adelaide Hills). In 2021, she was awarded the Peter Davies Memorial Prize for Creative Writing. She has recently completed an Honours in Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide. Nilofar Zimmerman is a writer and lawyer living in Sydney. She is currently undertaking a Master of Creative Writing at the University of Sydney and was the runner-up in the 2022 Deborah Cass Prize for Writing.

Nilofar Zimmerman is a writer and lawyer living in Sydney. She is currently undertaking a Master of Creative Writing at the University of Sydney and was the runner-up in the 2022 Deborah Cass Prize for Writing. Min Chow is an emerging Malaysian-Australian writer and second runner up for the Deborah Cass Prize in 2022. She works, lives and writes on Wurundjeri land. Her work has also appeared in the Life in the Time of Corona anthology and Peril magazine. She is working on her first novel.

Min Chow is an emerging Malaysian-Australian writer and second runner up for the Deborah Cass Prize in 2022. She works, lives and writes on Wurundjeri land. Her work has also appeared in the Life in the Time of Corona anthology and Peril magazine. She is working on her first novel. Peter Ramm is a poet and teacher who writes on the Gundungurra lands of the NSW Southern Highlands. His debut poetry collection Waterlines is out now with Vagabond Press. In 2022 he won the prestigious Manchester Poetry Prize. His poems have also won the Harri Jones Memorial Award, The South Coast Writers Centre Poetry Award, The Red Room Poetry Object, and have been shortlisted in the Bridport, ACU, Blake, and the Newcastle Poetry Prizes. His work has appeared in Westerly, Cordite, Plumwood Mountain, The Rialto, Eureka Street, and more.

Peter Ramm is a poet and teacher who writes on the Gundungurra lands of the NSW Southern Highlands. His debut poetry collection Waterlines is out now with Vagabond Press. In 2022 he won the prestigious Manchester Poetry Prize. His poems have also won the Harri Jones Memorial Award, The South Coast Writers Centre Poetry Award, The Red Room Poetry Object, and have been shortlisted in the Bridport, ACU, Blake, and the Newcastle Poetry Prizes. His work has appeared in Westerly, Cordite, Plumwood Mountain, The Rialto, Eureka Street, and more. Michelle Cahill is an Australian novelist and poet of Indian origin. They live in Sydney; their prizes include the the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing, the Kingston Writing School Hilary Mantel International Short Story Prize, the Val Vallis Award and the Red Room Poetry Fellowship. Their work appears in Future Library, ed Anjum Hassan & Sampurna Chatterjee, (Red Hen Press, 2022) and forthcoming in 4A Papers. Daisy & Woolf is published by Hachette.

Michelle Cahill is an Australian novelist and poet of Indian origin. They live in Sydney; their prizes include the the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing, the Kingston Writing School Hilary Mantel International Short Story Prize, the Val Vallis Award and the Red Room Poetry Fellowship. Their work appears in Future Library, ed Anjum Hassan & Sampurna Chatterjee, (Red Hen Press, 2022) and forthcoming in 4A Papers. Daisy & Woolf is published by Hachette. ALICIA MARSDEN is an Australian reviewer, bookseller and student. She studies law, literature and politics at the University of Queensland, and is passionate about the overlap between legal studies and literature, namely the gothic. She blogs about books and her current literary musings on Instagram, @dashedwithprose.

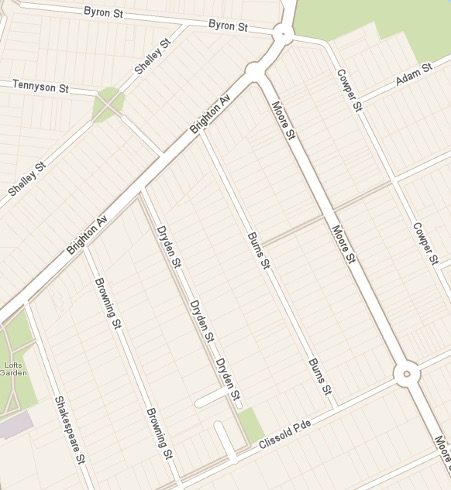

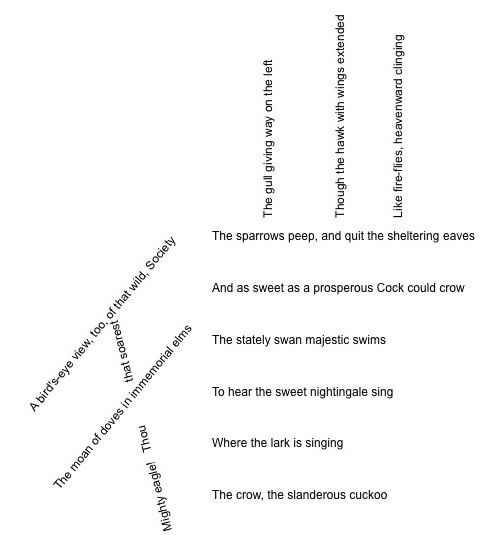

ALICIA MARSDEN is an Australian reviewer, bookseller and student. She studies law, literature and politics at the University of Queensland, and is passionate about the overlap between legal studies and literature, namely the gothic. She blogs about books and her current literary musings on Instagram, @dashedwithprose. Sydney Spleen

Sydney Spleen  Open Secrets

Open Secrets Audrey Molloy is an Irish-Australian poet based in Sydney. Her debut collection, The Important Things (The Gallery Press, 2021), received the 2021 Anne Elder Award and was shortlisted for the 2022 Seamus Heaney First Collection Poetry Prize. Ordinary Time, a collaboration with Anthony Lawrence, was published by Pitt Street Poetry in 2022. She has an MA in Creative Writing (Poetry) from Manchester Metropolitan University. Her work has appeared in Meanjin, Cordite, Overland, Magma, The North, Poetry Ireland Review, Mslexia, and Stand.

Audrey Molloy is an Irish-Australian poet based in Sydney. Her debut collection, The Important Things (The Gallery Press, 2021), received the 2021 Anne Elder Award and was shortlisted for the 2022 Seamus Heaney First Collection Poetry Prize. Ordinary Time, a collaboration with Anthony Lawrence, was published by Pitt Street Poetry in 2022. She has an MA in Creative Writing (Poetry) from Manchester Metropolitan University. Her work has appeared in Meanjin, Cordite, Overland, Magma, The North, Poetry Ireland Review, Mslexia, and Stand.  Stuart Barnes is the author of Like to the Lark (Upswell Publishing, 2023) and Glasshouses (UQP, 2016), which won the 2015 Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize, was commended for the 2016 Anne Elder Award and shortlisted for the 2017 Mary Gilmore Award. His work has been widely anthologised and published, including in Admissions: Voices within Mental Health, The Anthology of Australian Prose Poetry, Best of Australian Poems 2022, The Moth and POETRY (Chicago). Recently he guest co-edited, with Claire Gaskin, Australian Poetry Journal 11.1 ‘local, attention’. His ’Sestina after B. Carlisle’ won the 2021/22 Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize. @StuartABarnes

Stuart Barnes is the author of Like to the Lark (Upswell Publishing, 2023) and Glasshouses (UQP, 2016), which won the 2015 Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize, was commended for the 2016 Anne Elder Award and shortlisted for the 2017 Mary Gilmore Award. His work has been widely anthologised and published, including in Admissions: Voices within Mental Health, The Anthology of Australian Prose Poetry, Best of Australian Poems 2022, The Moth and POETRY (Chicago). Recently he guest co-edited, with Claire Gaskin, Australian Poetry Journal 11.1 ‘local, attention’. His ’Sestina after B. Carlisle’ won the 2021/22 Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize. @StuartABarnes Originally from a sunny island in Southeast Asia, Sher Ting is a Singaporean-Chinese currently residing in Australia. She is a 2021 Writeability Fellow with Writers Victoria and a Pushcart and Best of The Net nominee with work published/forthcoming in Pleiades, Colorado Review, OSU The Journal, The Pinch, Salamander, Chestnut Review, Rust+Moth and elsewhere. Her debut chapbook, Bodies of Separation, is forthcoming with Cathexis Northwest Press, and her second chapbook, The Long-Lasting Grief of Foxes, is forthcoming with CLASH! Books in 2023. She tweets at @sherttt and writes at sherting.carrd.co

Originally from a sunny island in Southeast Asia, Sher Ting is a Singaporean-Chinese currently residing in Australia. She is a 2021 Writeability Fellow with Writers Victoria and a Pushcart and Best of The Net nominee with work published/forthcoming in Pleiades, Colorado Review, OSU The Journal, The Pinch, Salamander, Chestnut Review, Rust+Moth and elsewhere. Her debut chapbook, Bodies of Separation, is forthcoming with Cathexis Northwest Press, and her second chapbook, The Long-Lasting Grief of Foxes, is forthcoming with CLASH! Books in 2023. She tweets at @sherttt and writes at sherting.carrd.co Brooke Maddison is a writer and editor working on unceded Turrbal and Yuggera land. She is completing a Masters of Writing, Editing and Publishing at the University of Queensland and is the founder and co-editor of Crackle (Corella Press, 2021), the university’s anthology of creative writing. Her work has been published by Kill Your Darlings, Antithesis and Spineless Wonders, among others. She has a mentorship with University of Queensland Press and is a 2022 recipient of The Next Chapter fellowship.

Brooke Maddison is a writer and editor working on unceded Turrbal and Yuggera land. She is completing a Masters of Writing, Editing and Publishing at the University of Queensland and is the founder and co-editor of Crackle (Corella Press, 2021), the university’s anthology of creative writing. Her work has been published by Kill Your Darlings, Antithesis and Spineless Wonders, among others. She has a mentorship with University of Queensland Press and is a 2022 recipient of The Next Chapter fellowship. Dean Mokrozhaevy moved to Australia in 2008 and grew up reading and writing in various suburbs of Sydney. They use their writing to work through their emotions and make something meaningful out of distress. Outside of their writing endeavours they also enjoy bushwalking, watching moon jellyfish in the Sydney harbour and sewing with their assistant Concrete the cat.

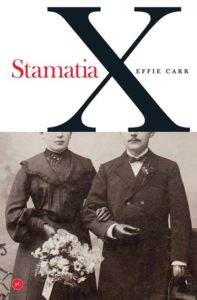

Dean Mokrozhaevy moved to Australia in 2008 and grew up reading and writing in various suburbs of Sydney. They use their writing to work through their emotions and make something meaningful out of distress. Outside of their writing endeavours they also enjoy bushwalking, watching moon jellyfish in the Sydney harbour and sewing with their assistant Concrete the cat. Stamiata X

Stamiata X

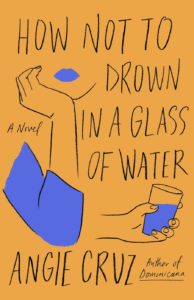

How not to Drown in a Glass of Water

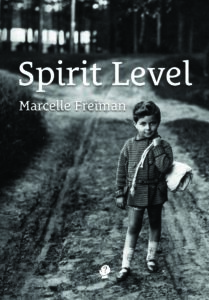

How not to Drown in a Glass of Water Spirit Level

Spirit Level Unsettled

Unsettled Clean

Clean mō taku tama

mō taku tama Body Shell Girl

Body Shell Girl My Pen is the Wing of a Bird: New Fiction by Afghan Women

My Pen is the Wing of a Bird: New Fiction by Afghan Women Homesickness

Homesickness Nostalgia Has Ruined My Life

Nostalgia Has Ruined My Life Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray

Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray Daisy and Woolf

Daisy and Woolf SOPHIE CUNNINGHAM’S latest novel, This Devastating Fever, is forthcoming in September 2022 with Ultimo Press. She is the author of seven books, across multiple fiction and nonfiction, children and adults and include City of Trees – Essays on life, death and the need for a forest, and Melbourne. She is also editor of the collection Fire, Flood, Plague: Australian writers respond to 2020. Sophie’s former roles include as a book publisher and editor, chair of the Literature Board of the Australia Council, editor of the literary journal Meanjin, and co-founder of The Stella Prize celebrating women’s writing. She is now an adjunct professor at RMIT University’s non/fiction Lab. In 2019, Sophie was made a Member of the Order of Australia for her contributions to literature.

SOPHIE CUNNINGHAM’S latest novel, This Devastating Fever, is forthcoming in September 2022 with Ultimo Press. She is the author of seven books, across multiple fiction and nonfiction, children and adults and include City of Trees – Essays on life, death and the need for a forest, and Melbourne. She is also editor of the collection Fire, Flood, Plague: Australian writers respond to 2020. Sophie’s former roles include as a book publisher and editor, chair of the Literature Board of the Australia Council, editor of the literary journal Meanjin, and co-founder of The Stella Prize celebrating women’s writing. She is now an adjunct professor at RMIT University’s non/fiction Lab. In 2019, Sophie was made a Member of the Order of Australia for her contributions to literature. Where We Swim

Where We Swim Nothing to See

Nothing to See Writing Through Fences: Archipelago of Letters

Writing Through Fences: Archipelago of Letters The Pigeons Are Taking Over: The Kindness of Birds

The Pigeons Are Taking Over: The Kindness of Birds  Love & Virtue

Love & Virtue Born Into This

Born Into This Exo-Dimensions, Mixed Feelings, Storm Warning

Exo-Dimensions, Mixed Feelings, Storm Warning by Seraphina Newberry & Justin Randall, Declan Miller, Lauren Boyle & Alyssa Mason

by Seraphina Newberry & Justin Randall, Declan Miller, Lauren Boyle & Alyssa Mason

Everything, all at Once

Everything, all at Once Eurydice Speaks

Eurydice Speaks Anthropocene

Anthropocene An Embroidery of Old Maps and New

An Embroidery of Old Maps and New  AJ DeMoyer is an emerging writer of eco-dystopian short fiction, currently studying an MA Writing and Literature at Deakin University. April lives with her husband, two tiny dogs and an oversize cat on Dharawal Country (regional NSW). When she’s not studying, reading or writing, she’s either propagating succulents in her garden, obsessively sorting

AJ DeMoyer is an emerging writer of eco-dystopian short fiction, currently studying an MA Writing and Literature at Deakin University. April lives with her husband, two tiny dogs and an oversize cat on Dharawal Country (regional NSW). When she’s not studying, reading or writing, she’s either propagating succulents in her garden, obsessively sorting  Juanita is an emerging writer who lives in a small town in rural Victoria, on the unceded land of the Dja Dja Wurrung people. She has only recently tapped into a deep desire to write. Having successfully navigated away from a long career as a professional photographer, Juanita is now completing her arts degree in anthropology and creative writing at Deakin University in Geelong.

Juanita is an emerging writer who lives in a small town in rural Victoria, on the unceded land of the Dja Dja Wurrung people. She has only recently tapped into a deep desire to write. Having successfully navigated away from a long career as a professional photographer, Juanita is now completing her arts degree in anthropology and creative writing at Deakin University in Geelong. Sushma Joshi is a writer and filmmaker from Nepal. She has written two books of short stories. “The End of the World” was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor Short Story Award. She has a BA in international relations from Brown University and an MA in English Literature from Middlebury College (USA) She is currently working on a Ph.D on environmental governance at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at Otago University, New Zealand.

Sushma Joshi is a writer and filmmaker from Nepal. She has written two books of short stories. “The End of the World” was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor Short Story Award. She has a BA in international relations from Brown University and an MA in English Literature from Middlebury College (USA) She is currently working on a Ph.D on environmental governance at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at Otago University, New Zealand.

Megan Cheong is a teacher, writer and critic living and working on Wurundjeri land. Her writing has been published in

Megan Cheong is a teacher, writer and critic living and working on Wurundjeri land. Her writing has been published in  Dinasha Edirisinghe was born in Sri Lanka and raised in Australia. She has completed a Bachelor of Arts and a Masters of Creative Writing, Publishing and Editing at The University of Melbourne and is currently completing her PhD at Deakin University. Her dissertation explores the creative work of the French feminist theorist Hélène Cixous and the Australian writer Patrick White. It also includes a novella called

Dinasha Edirisinghe was born in Sri Lanka and raised in Australia. She has completed a Bachelor of Arts and a Masters of Creative Writing, Publishing and Editing at The University of Melbourne and is currently completing her PhD at Deakin University. Her dissertation explores the creative work of the French feminist theorist Hélène Cixous and the Australian writer Patrick White. It also includes a novella called  Bryant Apolonio is an award-winning writer and lawyer currently living on Larrakia Country. He won the Deborah Cass Prize in 2021. His fiction has appeared in places like Liminal, Kill Your Darlings and Overland. He is working on a collection of short stories.

Bryant Apolonio is an award-winning writer and lawyer currently living on Larrakia Country. He won the Deborah Cass Prize in 2021. His fiction has appeared in places like Liminal, Kill Your Darlings and Overland. He is working on a collection of short stories. Patrick Arulanandam is a writer and doctor of Sri Lankan Tamil heritage, who lives on Wangal country in Sydney. He spends much his time using the NATO phonetic alphabet to spell his surname for people. He was second runner up for the Deborah Cass Prize in 2021, and a finalist for the Eric Dark Creative Writing Prize in 2014.

Patrick Arulanandam is a writer and doctor of Sri Lankan Tamil heritage, who lives on Wangal country in Sydney. He spends much his time using the NATO phonetic alphabet to spell his surname for people. He was second runner up for the Deborah Cass Prize in 2021, and a finalist for the Eric Dark Creative Writing Prize in 2014.

Belle is a non-binary writer from regional NSW, most of their work is based around LGBTQ+ topics and working towards a greener future. They also love a good oat milk iced latte.

Belle is a non-binary writer from regional NSW, most of their work is based around LGBTQ+ topics and working towards a greener future. They also love a good oat milk iced latte.

Craig Santos Perez is an indigenous Pacific Islander poet from Guåhan (Guam). He is the author of five books of poetry and the co-editor of five anthologies. He teaches at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa.

Craig Santos Perez is an indigenous Pacific Islander poet from Guåhan (Guam). He is the author of five books of poetry and the co-editor of five anthologies. He teaches at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. Dave Drayton was an amateur banjo player, founding member of the Atterton Academy, and the author of E, UIO, A: a feghoot (Container), A pet per ably-faced kid (Stale Objects dePress), P(oe)Ms (Rabbit), Haiturograms (Stale Objects dePress) and Poetic Pentagons (Spacecraft Press).

Dave Drayton was an amateur banjo player, founding member of the Atterton Academy, and the author of E, UIO, A: a feghoot (Container), A pet per ably-faced kid (Stale Objects dePress), P(oe)Ms (Rabbit), Haiturograms (Stale Objects dePress) and Poetic Pentagons (Spacecraft Press).

Author of four books of poetry, Two Full Moons (Bombaykala Books), Words Not Spoken (Brown Critique), The Longest Pleasure (Finishing Line Press) and The Silk Of Hunger (AuthorsPress), Vinita is an award winning poet, editor, translator and curator. Joint recipient of the Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize 2018 and winner of the Gayatri GaMarsh Memorial Award for Literary Excellence USA 2015. She is Poetry Editor with Usawa Literary Review. Her work has been widely published and anthologised. Her poem won a prize for the Moon Anthology on the Moon by TallGrass Writers Guild, Chicago 2017. More recently her poem won a special mention in the Hawker Prize for best South Asian poetry. She has contributed a monthly column on Asian Poets on the literary blog of the Hamline University, Saint Paul USA in 2016-17. In September 2020, she edited an anthology on climate change titled Open Your Eyes (pub. Hawakal). Most recently she co-edited the Yearbook of Indian Poetry in English 2020-21 (Hawakal). She judged the RLFPA poetry contest (International Prize) in 2016 and co judged the Asian Cha’s poetry contest on The Other Side in 2015. She was featured in a documentary on twenty women poets from Asia, produced in Taiwan. She has read at the FILEY Book Fair, Merida, Mexico, Kala Ghoda Arts Festival among others. She is on the Advisory Board of the Tagore Literary Prize. She has curated literary events for PEN Mumbai. Read more about her at www.vinitawords.com

Author of four books of poetry, Two Full Moons (Bombaykala Books), Words Not Spoken (Brown Critique), The Longest Pleasure (Finishing Line Press) and The Silk Of Hunger (AuthorsPress), Vinita is an award winning poet, editor, translator and curator. Joint recipient of the Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize 2018 and winner of the Gayatri GaMarsh Memorial Award for Literary Excellence USA 2015. She is Poetry Editor with Usawa Literary Review. Her work has been widely published and anthologised. Her poem won a prize for the Moon Anthology on the Moon by TallGrass Writers Guild, Chicago 2017. More recently her poem won a special mention in the Hawker Prize for best South Asian poetry. She has contributed a monthly column on Asian Poets on the literary blog of the Hamline University, Saint Paul USA in 2016-17. In September 2020, she edited an anthology on climate change titled Open Your Eyes (pub. Hawakal). Most recently she co-edited the Yearbook of Indian Poetry in English 2020-21 (Hawakal). She judged the RLFPA poetry contest (International Prize) in 2016 and co judged the Asian Cha’s poetry contest on The Other Side in 2015. She was featured in a documentary on twenty women poets from Asia, produced in Taiwan. She has read at the FILEY Book Fair, Merida, Mexico, Kala Ghoda Arts Festival among others. She is on the Advisory Board of the Tagore Literary Prize. She has curated literary events for PEN Mumbai. Read more about her at www.vinitawords.com Tim Loveday is a poet, a writer, and an editor. As the recipient of a 2020 Next Chapter Wheeler Centre Fellowship and a 2021 Varuna Residential Fellowship, his work aims to challenge toxic masculinity in Australia. His poetry/prose has appeared in Meanjin, Cordite, The Big Issue, Babyteeth, Meniscus, Text Journal, and The Big Smoke, among others. A Neurodivergent dog parent, he is the verse editor for XR’s Creative Hub. Tim currently resides in North Melbourne, the traditional land of the Wurundjeri people.

Tim Loveday is a poet, a writer, and an editor. As the recipient of a 2020 Next Chapter Wheeler Centre Fellowship and a 2021 Varuna Residential Fellowship, his work aims to challenge toxic masculinity in Australia. His poetry/prose has appeared in Meanjin, Cordite, The Big Issue, Babyteeth, Meniscus, Text Journal, and The Big Smoke, among others. A Neurodivergent dog parent, he is the verse editor for XR’s Creative Hub. Tim currently resides in North Melbourne, the traditional land of the Wurundjeri people. Sonnet Mondal writes from Kolkata and is the author of An Afternoon in My Mind (Copper Coin, 2021), Karmic Chanting (Copper Coin, 2018), Ink and Line (Dhauli Books, 2018), and five other books of poetry. He serves as the director of Chair Poetry Evenings-Kolkata’s International Poetry Festival and managing editor of Verseville.

Sonnet Mondal writes from Kolkata and is the author of An Afternoon in My Mind (Copper Coin, 2021), Karmic Chanting (Copper Coin, 2018), Ink and Line (Dhauli Books, 2018), and five other books of poetry. He serves as the director of Chair Poetry Evenings-Kolkata’s International Poetry Festival and managing editor of Verseville. Rachael Mead is a novelist and award-winning poet and short story writer, with her creative work appearing widely in Australia and internationally. She’s the author of the novel The Application of Pressure (Affirm Press 2020) and four collections of poetry including The Flaw in the Pattern (UWAP 2018). In 2019, she spent a month in the Taleggio Valley in Northern Italy on an eco-poetry residency awarded by Australian Poetry.

Rachael Mead is a novelist and award-winning poet and short story writer, with her creative work appearing widely in Australia and internationally. She’s the author of the novel The Application of Pressure (Affirm Press 2020) and four collections of poetry including The Flaw in the Pattern (UWAP 2018). In 2019, she spent a month in the Taleggio Valley in Northern Italy on an eco-poetry residency awarded by Australian Poetry. By November 2021, Ouyang Yu has published 137 books in both English and Chinese in the field of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, literary translation and criticism. His second book of English poetry, Songs of the Last Chinese Poet, was shortlisted for the 1999 NSW Premier’s Literary Award. His third novel, The English Class, won the 2011 NSW Premier’s Award, and his translation in Chinese of The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes won the Translation Award from the Australia-China Council in 2014. He won the Judith Wright Calanthe Award for a Poetry Collection in the 2021 Queensland Literary Awards, his bilingual blog at: youyang2.blogspot.com

By November 2021, Ouyang Yu has published 137 books in both English and Chinese in the field of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, literary translation and criticism. His second book of English poetry, Songs of the Last Chinese Poet, was shortlisted for the 1999 NSW Premier’s Literary Award. His third novel, The English Class, won the 2011 NSW Premier’s Award, and his translation in Chinese of The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes won the Translation Award from the Australia-China Council in 2014. He won the Judith Wright Calanthe Award for a Poetry Collection in the 2021 Queensland Literary Awards, his bilingual blog at: youyang2.blogspot.com Ojo Taiye is a young Nigerian poet who uses poetry as a handy tool to hide his frustration with society. He also makes use of collage and sample technique. He is the winner of many prestigious awards including the 2021 Hay Writer’s Circle Poetry Competition, 2021 Cathalbui Poetry Competition, Ireland.

Ojo Taiye is a young Nigerian poet who uses poetry as a handy tool to hide his frustration with society. He also makes use of collage and sample technique. He is the winner of many prestigious awards including the 2021 Hay Writer’s Circle Poetry Competition, 2021 Cathalbui Poetry Competition, Ireland. Monique Lyle is a DCA candidate with the writing centre at Western Sydney University. She is currently completing her first manuscript, The Park, which explores her experiences growing up in Sydney Housing Commission in the 90’s. Recently her work has appeared in Overland, Flash Cove, Otoliths, Plumwood Mountain and also Dance Research.

Monique Lyle is a DCA candidate with the writing centre at Western Sydney University. She is currently completing her first manuscript, The Park, which explores her experiences growing up in Sydney Housing Commission in the 90’s. Recently her work has appeared in Overland, Flash Cove, Otoliths, Plumwood Mountain and also Dance Research. Lisa Nan Joo lives on Gadigal land and is an emerging writer of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. Her work has previously appeared in Kill Your Darlings, Strange Horizons, Meniscus, Seizure Online and Spineless Wonders.

Lisa Nan Joo lives on Gadigal land and is an emerging writer of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. Her work has previously appeared in Kill Your Darlings, Strange Horizons, Meniscus, Seizure Online and Spineless Wonders. Lawdenmarc Decamora is a Best of the Net and Pushcart Prize-nominated writer with work published in 23 countries around the world. He is the author of three book-length poetry collections, Love, Air (Atmosphere Press, 2021), TUNNELS (Ukiyoto Publishing, 2021), and Handsome Hope which is forthcoming from Yorkshire Publishing in 2022. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in places like The Common, The Seattle Review, Columbia Review, North Dakota Quarterly, California Quarterly, Cordite Poetry Review, AAWW’s The Margins, and elsewhere. His poetry will be anthologized in The Best Asian Poetry 2021 and had recently appeared in the best-selling Meridian: The APWT Drunken Boat Anthology of New Writing. In the UK, Lawdenmarc’s poetry was long-listed for The Alpine Fellowship Writing Prize 2021 and shortlisted for Aesthetica Creative Writing Award 2021 (Aesthetica Magazine). He was an August 2021 alumnus of the Tupelo Press 30/30 Project of the US-based Tupelo Press, and is also a member of the Asia Pacific Writers & Translators (APWT). He lives in the Philippines where he teaches literature at the oldest existing Catholic university in Asia, the University of Santo Tomas (UST).

Lawdenmarc Decamora is a Best of the Net and Pushcart Prize-nominated writer with work published in 23 countries around the world. He is the author of three book-length poetry collections, Love, Air (Atmosphere Press, 2021), TUNNELS (Ukiyoto Publishing, 2021), and Handsome Hope which is forthcoming from Yorkshire Publishing in 2022. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in places like The Common, The Seattle Review, Columbia Review, North Dakota Quarterly, California Quarterly, Cordite Poetry Review, AAWW’s The Margins, and elsewhere. His poetry will be anthologized in The Best Asian Poetry 2021 and had recently appeared in the best-selling Meridian: The APWT Drunken Boat Anthology of New Writing. In the UK, Lawdenmarc’s poetry was long-listed for The Alpine Fellowship Writing Prize 2021 and shortlisted for Aesthetica Creative Writing Award 2021 (Aesthetica Magazine). He was an August 2021 alumnus of the Tupelo Press 30/30 Project of the US-based Tupelo Press, and is also a member of the Asia Pacific Writers & Translators (APWT). He lives in the Philippines where he teaches literature at the oldest existing Catholic university in Asia, the University of Santo Tomas (UST). Jennifer Compton lives in Melbourne and is a poet and playwright who also writes prose. Her 11th book of poetry, the moment, taken was published by Recent Work Press in 2021.

Jennifer Compton lives in Melbourne and is a poet and playwright who also writes prose. Her 11th book of poetry, the moment, taken was published by Recent Work Press in 2021. Greg Page is a Koori Poet from the La Perouse community at Kamay (Botany Bay). He holds an M.A. in Creative Writing from UTS in Sydney and has been published in the Australian Poetry Journal and the Koori Mail. He lives on unceded Bidjigal land. Dox him at