Edwidge Danticat was born in Haiti in 1969 and moved to the United States when she was twelve. She is the author of two novels, two collections of stories, two books for young adults, and two nonfiction books, one of which, Brother, I’m Dying, was a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for autobiography. In 2009, she received a MacArthur Fellowship. Her most recent collection of essays is Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist At Work. She is the editor for Haiti Noir.

Edwidge Danticat was born in Haiti in 1969 and moved to the United States when she was twelve. She is the author of two novels, two collections of stories, two books for young adults, and two nonfiction books, one of which, Brother, I’m Dying, was a finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for autobiography. In 2009, she received a MacArthur Fellowship. Her most recent collection of essays is Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist At Work. She is the editor for Haiti Noir.

from Brother, I’m Dying

Listening to my father, I remembered a time when I used to dream of smuggling him words. I was eight years old and Bob and I were living in Haiti with his oldest brother, my uncle Joseph, and his wife. And since they didn’t have a telephone at home—few Haitian families did then—and access to the call centres was costly, we had no choice but to write letters. Every other month, my father would mail a half-page, three-paragraph missive addressed to my uncle. Scribbled in his miniscule scrawl, sometimes on plain white paper, other times on lined, hole-punched notebook pages still showing bits of fringe from the spiral binding, my father’s letters were composed in stilted French, with the first paragraph offering news of his and my mother’s health, the second detailing how to spend the money they had wired for food, lodging and school expenses for Bob and myself, the third section concluding abruptly after reassuring us that we’d be hearing from him again before long.

Later I would discover in a first-year college composition class that his letters had been written in a diamond sequence, the Aristotelian Poetics of correspondence, requiring an opening greeting, a middle detail or request, and a brief farewell at the end. The letter-writing process had been such an agonising chore for my father, one that he’d hurried through while assembling our survival money, that this specific epistolary formula, which he followed unconsciously, had offered him a comforting way of disciplining his emotions.

“I was no writer,” he later told me. “What I wanted to tell you and your brother was too big for any piece of paper and a small envelope.”

Whatever restraint my father showed in his letters was easily compensated for by Uncle Joseph’s reactions to them. First there was the public reading in my uncle’s sparsely furnished pink living room, in front of Tante Denise, Bob and me. This was done so there would be no misunderstanding as to how the money my parents sent for me and my brother would be spent. Usually my uncle would read the letters out loud, pausing now and then to ask my help with my father’s penmanship, a kindness, I thought; a way to include me a step further. It soon became obvious, however, that my father’s handwriting was a as clear to me as my own, so I eventually acquired the job of deciphering his letters.

Along with this task came a few minutes of preparation for the reading and thus a few intimate moments with my father’s letters, not only the words and phrases, which did not vary greatly from month to month, but the vowels and syllables, their tilts and slants, which did. Because he wrote so little, I would try to guess his thoughts and moods from the dotting of his i’s and the crossing of his t’s, from whether there were actual periods at the ends of his sentences or just faint dots where the tip of his pen had simply landed. Did commas split his streamlined phrases, or were they staccato, like someone speaking too rapidly, out of breath?

For the family readings, I recited my father’s letters in a monotone, honouring what I interpreted as a secret between us, that the impersonal style of his letters was due as much to his lack of faith in words and their ability to accurately reproduce his emotions as to his caution with Bob’s and my feelings, avoiding too-happy news that might add to the anguish of separation, too-sad news that might worry us, and any hint of judgement or disapproval for my aunt and uncle, which they could have interpreted as suggestions that they were mistreating us. The dispassionate letters were his way of avoiding a minefield, one he could have set off from a distance without being able to comfort the victims.

Given all this anxiety, I’m amazed my father wrote at all. The regularity, the consistency of his correspondence now feels like an act of valor. In contrast, my replies, though less routine—Uncle Joseph did most of the writing—were both painstakingly upbeat and suppliant. In my letters, I bragged about my good grades and requested, as a reward for them, an American doll at Christmas, a typewriter or sewing machine for my birthday, a pair of “real” gold earrings for Easter. But the things I truly wanted I was afraid to ask for, like when I would finally see him and my mother again. However, since my uncle read and corrected all my letters for faulty grammar and spelling, I wrote for his eyes more than my father’s, hoping that even after the vigorous editing, my father would still decode the longing in my childish cursive slopes and arches, which were so much like his own.

The words that both my father and I wanted to exchange we never did. These letters were not approved, in his case by him, in my case by my uncle. No matter what the reason, we have always been equally paralysed by the fear of breaking each other’s heart. This is why I could never ask the question Bob did. I also could never tell my father that I’d learned from the doctor that he was dying. Even when they mattered less, there were things he and I were too afraid to say.

A few days after the family meeting, my father called my uncle Joseph in Haiti, to see how he was doing. It was Thursday, July 15, 2004, the fifty-first birthday of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Haiti’s twice-elected and twice-deposed president. Having been removed from power in February 2004 through a joint political action by France, Canada and the United States, Aristide was now spending his birthday in exile in South Africa. However, the residents of Bel Air, the neighbourhood where I grew up and where my uncle Joseph still lived, had not forgotten him. Joining other Aristide supporters, they’d marched, nearly three thousand of them, through the Haitian capital to call for his return. The march had been mostly peaceful, except that, according to the television news reports that my father and I had watched together that evening, two policemen had been shot. My father called my uncle, just as he always did whenever something like this was happening in Haiti. He was sitting up in bed, his head propped on two firm pillows, his face angled toward the bedroom window, which allowed him a slanted view of a neighbourhood street lamp.

“Are you sure he’s sleeping?” my father asked whoever had answered the phone at my uncle’s house in Bel Air.

My father cupped the phone with one hand, pushed his face toward me and whispered “Maxo.”

I gathered he was talking to Uncle Joseph’s son, Maxo, who had left Haiti in the early 1970’s to attend college in New York, then had returned in 1995. Though I had spent most of my childhood with Maxo’s son Nick, I did not know Maxo as well.

“Don’t you think it’s time your father moved out of Bel Air?” my father asked Maxo.

As he hung up, he seemed disappointed that he hadn’t been able to speak to Uncle Joseph. Over the years, this had been a touchy subject between my father and uncle: my father wanting my uncle to move to another part, any other part, of Haiti and my uncle refusing to even consider it. I now imagined my father longing to tell his brother to leave Bel Air, but this time not for the reasons he usually offered—the constant demonstrations, the police raids and gang wars that caused him to constantly worry—but because my father was dying and he wanted his oldest brother to be safe.

I write these things now, some as I witnessed them and today remember them, others from official documents, as well as the borrowed recollections of family members. But the gist of them was told to me over the years, in part by my uncle Joseph, in part by my father. Some were told offhand, quickly. Others, in greater detail. What I learned from my father and uncle, I learned out of sequence and in fragments. This is an attempt at cohesiveness, and at re-creating a few wondrous and terrible months when their lives and mine intersected in startling ways, forcing me to look forward and back at the same time. I am writing this only because they can’t.

—- Citation: Brother, I’m Dying, Scribe Publications, copyright 2007, page 21-26

~~~~~~~~~~

from Create Dangerously:The Immigrant Artist At Work

Twenty-three days after the earthquake, my first trip to Haiti is brief, too brief. A friend finds a last-minute cancellation on a relief plane. Another agrees to help my husband look after our young girls in Miami.

I arrive in Port-au-Prince at an airport with cracked walls and broken windows. The fields around the runway are packed with American military helicopters and planes. Past a card table manned by three Haitian immigration officers, a group of young American soldiers idle, cradling what seem like machine guns. Through an arrangement between the Haitian and the U.S. governments, the American military as leader in the relief effort, has taken over Toussaint L’Ouverture Airport.

Outside the airport, my friend Jhon Charles, a painter, and my husband’s uncle, whom we call Tonton Jean, are waiting for me. A small man, Tonton Jean still cuts a striking figure with the dark motorcycle helmet he wears everywhere now to protect himself from falling debris. Jhon and Tonton Jean are standing behind a barricade near where the Americans have set up a Customs and Border Protection operation at the airport.

Whose borders are they protecting? I wonder. I soon get my answer. People with Haitian passports are not being allowed to enter the airport.

Maxo’s oldest son, Nick, who now lives in Canada, is also in Haiti. He arrived a few days before I did to pay his respects and see what he could do for his brothers and sisters, who had been pulled, some of them wounded, from the rubble of the family house in Bel Air. When I arrive in Port-au-Prince, Nick is at the General Hospital with two of his siblings, getting them follow-up care.

One of the boys, thirteen-year-old Maxime, has already lost a toe to gangrene. Nick was told that his eight-year-old-sister, Monica, might need to have her foot amputated, but the American doctors who are taking care of her in a tent clinic in the yard of Port-au-Prince’s main hospital think that they may be able to save her foot. This makes Monica luckier than a lot of other people I see hobbling on crutches all over Port-au-Prince, their newly amputated limbs covered bys shirt or blouse sleeves or pant legs carefully folded and pinned with large safety pins.

I am heading to the hospital to see Nick and the children when I get my first view of the areas surrounding my old neighbourhood. Every other structure, it seems, is completely or partially destroyed. The school I attended as a girl is no more. The national cathedral, where my entire school was brought to attend mass every Friday, has collapsed. The house of the young teacher who tutored me when I fell behind in school has caved in, with most of her family members inside. The Lycée Petion, where generations of Haitian men had been educated, is gone. The Centre d’Art, which had nurtured thousands of Haitian artists, is barely standing. The Sainte-Trinité Church, where a group of famous Haitian artists had painted a stunning series of murals depicting the life of Christ, has crumbled, leaving only a section of lacerated wall, where a wounded Christ seems to be ascending toward an open sky. Grand Rue, downtown Port-au-Prince’s main thoroughfare, looks as though it had been bombed for several consecutive days. Standing in the middle of it reminds me of film I had seen of a destroyed Hiroshima. With its gorgeous white domes either tipped over or caved in, the national palace is the biggest symbol of the Haitian government’s monumental loss of human and structural capital. Around the national palace has sprung up a massive tent city, filled with a patchwork of makeshift tents, actual tents, and semipermanent-looking corrugated tin structures, identical to those in dozens of other refugee camps all over the capital. The statues and monuments of the unknown maroon, a symbol of Haiti’s freedom from slavery, of Toussaint L’Ouverture, Henri Christophe, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and even a more recent massive globelike sculpture commissioned by President Jean-Bertrand Aristide to commemorate Haiti’s bicentennial in 2004—these monuments and symbols around the national palace are still standing; however, their platforms now serve as perches from which people bathe and children play.

Outside the nursing and midwifery schools near the General Hospital are piles of human remains freshly pulled from the rubble. Dense rings of flies surround them. The remains are stuck together in two large balls. I wonder out loud whether all these nursing and midwifery students had been embracing one another when the ceiling collapsed on top of them, their arms and legs crisscrossed and intertwined. My friend Jhon Charles corrects me.

“These are all body parts,” he says, “legs and arms that were pulled out the rubble and placed on the side of the road, where they dried further and melded together.” Sticking to several of the flesh-depleted legs are pieces of yellowed cloth-skirts, I realize, which many of the women must have been wearing.

Across the street from the remains, people line up to watch. One woman pleads with the crowd to repent. “Call on Jesus! He is all we have left.”

“We are nothing,” another man says, while holding a rag up against his nose. “Look at this, we are nothing.”

Jhon is a lively thirty-four-year old who under normal circumstances has an easy laugh. He has been drawing and painting since he was a boy, using up leftover materials from his artist father. Later he attended Haiti’s National School of the Arts, and has been painting and teaching art in secondary schools since he graduated. Even though he is at the beginning of his career, he has already participated in group shows in Port-au-Prince, New York, Miami, and Caracas, Venezuela. Jhon grew up in Carrefour, where Tonton Jean also lives. The epicenter of the earthquake was near Carrefour. A week after the earthquake, my husband and I were still trying to locate Jean and Tonton Jean. Their cell phones were not working and, besides, they were both very busy. Tonton Jean was pulling people out of the rubble and Jhon was teaching the traumatized children in the tent city near his house to draw.

In the tent clinic at the general hospital, I find Maxo’s son Maxime, sleeping on a bench near where Maxime’s sister Monica is attached to an antibiotic drip. All around Monica, wounded adults and children lie on their sides or backs on military cots. Most of the adults have vacant stares, while the children look around half-curious, examining each new person who walks in. I try to imagine what it must have been like in this tent and others like it during those first days after the earthquake, when, Tonton Jean tells me, people were showing up at the little clinic across the street from his house in Carrefour, without noses and ears or arms and legs.

In the tent clinic I say hello to Monica. She looks up at me and blinks but otherwise does not react. Her eyes are dimmed and it appears that she may still be in shock. To watch your house and neighbourhood, your city crumble, then to watch your father die, and then nearly to die yourself, all before your tenth birthday, seems like an insurmountable obstacle for any child.

Even before this tragedy, Monica was a shy girl. When I saw here during my visits to Haiti, she would speak to me only when she was told what to say. The same was true when I spoke to her on the phone. Now in the tent clinic, I gave her in the middle of her head, where her hair has been shaved in an uneven line to place a bandage where a piece of cement had split open her scalp.

Before I leave the tent hospital, the blonde young American doctor who is taking care of Monica gives her a yellow smiley-face sticker.

“She’s my brave little soldier,” the doctor says.

I thank her in English.

“You speak English very well,” she says, before moving to the severely dehydrated baby in the next cot.

My next family stop is in Delmas, to see my Tante Zi. Though it had not collapsed, her house, perched on a hill above a busy street, is too cracked to be habitable, so she is staying in a large tent city in an open field nearby. We had talked often after the earthquake, and her biggest fear was of being caught out there in the rain. I had pleaded with her to go to La Plaine, where we had other family members, but she did not want to leave her damaged house, fearing that it might be vandalized or razed while she was gone.

When I reach Tante Zi’s house, some of the family members from La Plaine, including NC, are there too. We are too afraid to go inside the house, so we all gather on the sidewalk out front, which is lined with tents and improvised showers. It astounds me how much more of Haitian life now takes place outside, the most intimate interactions casually unfolding before our eyes: a girl sitting between her boyfriend’s legs on a car hood, a woman bathing her elderly mother with a bowl and a bucket. These are things we might have seen before, but now they are reproduced in some variation in front of dozens of shattered or nearly shattered houses on almost every street.

I hug NC and Tante Zi and six of my other cousins and four of their children. They tell me about the others. The cousin with the broken back may possibly be airlifted out of the country. The others from La Plaine were still sleeping outside their house but through a contract in Port-au-Prince they had gotten some water. Everyone had received the money the family had put together and wired them for food. Through all this, we hold and cradle one another, and while I hand them the tents and tarp they had requested, I start repeating something I hear Tonton Jean say each time he runs into a friend.

“I’m glad you’re here. I’m glad bagay la-the thing-left you alive so I can see you.”

Bagay la, this thing that different people are calling different things, this thing that at that moment has no official name. This thing that my musician/hotelier friend Richard Morse calls Samson on his Twitter updates that Tonton Jean now and then calls Ti Roro, that Jhon calls Ti Rasta, that a few people calling in to a radio program are calling Goudougoudou.

“I am glad Goudougoudou left you alive so I can see you,” I say.

They laugh and their laughter fills me with more hope than the moment deserves. But this is really all I have come for. I have come to embrace them, the living, and I have come to honour the dead.

They show me their scrapes and bruises and I hug them some more, until my body aches. I take pictures for the rest of the family. I know everyone will be astounded by how well they look, how beautiful and well put together in their impeccable clothes. I love them so much. I am so proud of them. Still I ask myself how long they can live the way they are living, out in the open, waiting.

Two of them have tourist visas to Canada and the United States, but they stay because they cannot leave the others, who are mostly children. NC does not have a visa. She wants a student visa, to continue her accounting studies abroad. She hands me a manila envelope filled with documents, her birth certificate, her report cards, her school papers. She gives them to me for safekeeping, but also so I can see what I can do to get her out of the country.

NC, like many of my family members in Haiti, has always overestimated my ability to do things like this, to get people out of bad situations. I hope at that moment that she is right. I hope I can help. I have sometimes succeeded in helping, but mostly I have failed. Case in point: my elderly uncle died trying to enter the United States. I could not save him.

Citation: From the essay, ‘Our Guernica,’ which first appeared in Create Dangerously, Princeton University Press copyright 2010, pp. 162-169

Bo Schwabacher is an adopted Korean American writer. She explores the art of writing and teaching. She holds a Master’s Degree in English (emphasis in creative writing) and a Teaching English as a Second Language Certificate. Her poem “Korean American Tongue” has been published in Saltwater Quarterly. She currently resides in Flagstaff, Arizona.

Bo Schwabacher is an adopted Korean American writer. She explores the art of writing and teaching. She holds a Master’s Degree in English (emphasis in creative writing) and a Teaching English as a Second Language Certificate. Her poem “Korean American Tongue” has been published in Saltwater Quarterly. She currently resides in Flagstaff, Arizona.

Alan Gould has published twenty books, comprising novels, collections of poetry and a volume of essays. His most recent novel is The Lakewoman which is presently on the shortlist for the Prime Minister’s Fiction Award, and his most recent volume of poetry is Folk Tunes from Salt Publishing. ‘Works And Days’ comes from a picaresque novel entitled The Poets’ Stairwell, and has been recently completed.

Alan Gould has published twenty books, comprising novels, collections of poetry and a volume of essays. His most recent novel is The Lakewoman which is presently on the shortlist for the Prime Minister’s Fiction Award, and his most recent volume of poetry is Folk Tunes from Salt Publishing. ‘Works And Days’ comes from a picaresque novel entitled The Poets’ Stairwell, and has been recently completed. Maria Takolander’s poetry, fiction and essays have been widely published. She is the author of a book of poems, Ghostly Subjects(Salt, 2009), which was shortlisted for a Queensland Premier’s Literary Award in 2010. She is also the winner of the 2010 Australian Book Review Short Story Competition. She is a Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies and Creative Writing at Deakin University in Geelong.

Maria Takolander’s poetry, fiction and essays have been widely published. She is the author of a book of poems, Ghostly Subjects(Salt, 2009), which was shortlisted for a Queensland Premier’s Literary Award in 2010. She is also the winner of the 2010 Australian Book Review Short Story Competition. She is a Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies and Creative Writing at Deakin University in Geelong.

Porch Music

Porch Music

The Domestic Sublime

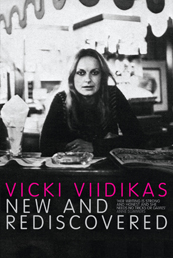

The Domestic Sublime New and Rediscovered

New and Rediscovered

Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist At Work

Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist At Work The Mary Smokes Boys

The Mary Smokes Boys

.jpg)

.jpg)

Jennifer Compton lives in Melbourne and is a poet and playwright who also writes prose. Her book of poetry – Barefoot – was published by Picaro Press in 2010 and her unpublished ms – This City – won the Kathleen Grattan Award and will be published by Otago University Press in July. Her stage play – The Third Age – has been short listed for the Adam New Zealand Play Award and she is hopeful that it will eventually be produced.

Jennifer Compton lives in Melbourne and is a poet and playwright who also writes prose. Her book of poetry – Barefoot – was published by Picaro Press in 2010 and her unpublished ms – This City – won the Kathleen Grattan Award and will be published by Otago University Press in July. Her stage play – The Third Age – has been short listed for the Adam New Zealand Play Award and she is hopeful that it will eventually be produced.

.jpg)

joanne burns is a Sydney poet. She has had many prose poems published, and is represented in The Indigo Book of Australian Prose Poems, Ginninderra Press 2011. Her most recent book is amphora, Giramondo Publishing 2011. She is working on a new poetry collection brush.

joanne burns is a Sydney poet. She has had many prose poems published, and is represented in The Indigo Book of Australian Prose Poems, Ginninderra Press 2011. Her most recent book is amphora, Giramondo Publishing 2011. She is working on a new poetry collection brush. Adam King grew up in Newcastle, Australia. For the past 15 years he has taught English—a decade or so in Osaka and, more recently, in Guangzhou.

Adam King grew up in Newcastle, Australia. For the past 15 years he has taught English—a decade or so in Osaka and, more recently, in Guangzhou. Among SMS’s books of poems and poetic prose are, most recently, And then something happened (Salt, 2004), Dementia Blog (Singing Horse, 2008), and the forthcomingMemory Cards: 2010-2011 Series. She wrote A Poetics of Impasse in Modern and Contemporary Poetry (U of Alabama, 2005), and edits Tinfish Press out of her home in Kane`ohe, Hawai`i. She’s taught at the University of Hawai`i-Manoa for over two decades. Her blog can be found at

Among SMS’s books of poems and poetic prose are, most recently, And then something happened (Salt, 2004), Dementia Blog (Singing Horse, 2008), and the forthcomingMemory Cards: 2010-2011 Series. She wrote A Poetics of Impasse in Modern and Contemporary Poetry (U of Alabama, 2005), and edits Tinfish Press out of her home in Kane`ohe, Hawai`i. She’s taught at the University of Hawai`i-Manoa for over two decades. Her blog can be found at  Sampurna Chattarji is a poet, novelist, and translator with eight books to her credit. Born in Ethiopia in November 1970, Sampurna grew up in Darjeeling, graduated from New Delhi, and is now based in Mumbai. Her debut poetry collection, Sight May Strike You Blind, was published by the Sahitya Akademi (Indian Academy of Letters) in 2007 and reprinted in 2008. Sampurna’s poetry has been anthologised in 60 Indian Poets(Penguin); Both Sides of The Sky (NBT); We Speak in Changing Languages (Sahitya Akademi); Interior Decoration: poems by 54 women from 10 languages (Women Unlimited); Fulcrum (Fulcrum Poetry Press, US) and The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poets (Bloodaxe, UK). Her 2004 translation of Sukumar Ray’s poetry and prose Abol Tabol: The Nonsense World of Sukumar Ray is now a Puffin Classic titled Wordygurdyboom! Sampurna’s most recent book for children is The Fried Frog and Other Funny Freaky Foodie Feisty Poems (Scholastic 2009). She is the author of two novels, Rupture (2009) and The Land of the Well (forthcoming 2011), both from HarperCollins.Absent Muses (Poetrywala, 2010) is her second poetry book. More about her work can be found at

Sampurna Chattarji is a poet, novelist, and translator with eight books to her credit. Born in Ethiopia in November 1970, Sampurna grew up in Darjeeling, graduated from New Delhi, and is now based in Mumbai. Her debut poetry collection, Sight May Strike You Blind, was published by the Sahitya Akademi (Indian Academy of Letters) in 2007 and reprinted in 2008. Sampurna’s poetry has been anthologised in 60 Indian Poets(Penguin); Both Sides of The Sky (NBT); We Speak in Changing Languages (Sahitya Akademi); Interior Decoration: poems by 54 women from 10 languages (Women Unlimited); Fulcrum (Fulcrum Poetry Press, US) and The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poets (Bloodaxe, UK). Her 2004 translation of Sukumar Ray’s poetry and prose Abol Tabol: The Nonsense World of Sukumar Ray is now a Puffin Classic titled Wordygurdyboom! Sampurna’s most recent book for children is The Fried Frog and Other Funny Freaky Foodie Feisty Poems (Scholastic 2009). She is the author of two novels, Rupture (2009) and The Land of the Well (forthcoming 2011), both from HarperCollins.Absent Muses (Poetrywala, 2010) is her second poetry book. More about her work can be found at Tim Wright lives in Melbourne in a house backing onto a train line. The poems for this issue were written in the south west of Western Australia and are part of a longer series.

Tim Wright lives in Melbourne in a house backing onto a train line. The poems for this issue were written in the south west of Western Australia and are part of a longer series. Geoff Page is an Australian poet who has published eighteen collections of poetry as well as two novels, four verse novels and several other works including anthologies, translations and a biography of the jazz musician, Bernie McGann. He retired at the end of 2001 from being in charge of the English Department at Narrabundah College in the ACT, a position he had held since 1974. He has won several awards, including the ACT Poetry Award, the Grace Leven Prize, the Christopher Brennan Award, the Queensland Premier’s Prize for Poetry and the 2001 Patrick White Literary Award. Selections from his work have been translated into Chinese, German, Serbian, Slovenian and Greek. He has also read his work and talked on Australian poetry in throughout Europe as well as in India, Singapore, China, Korea, the United States and New Zealand.

Geoff Page is an Australian poet who has published eighteen collections of poetry as well as two novels, four verse novels and several other works including anthologies, translations and a biography of the jazz musician, Bernie McGann. He retired at the end of 2001 from being in charge of the English Department at Narrabundah College in the ACT, a position he had held since 1974. He has won several awards, including the ACT Poetry Award, the Grace Leven Prize, the Christopher Brennan Award, the Queensland Premier’s Prize for Poetry and the 2001 Patrick White Literary Award. Selections from his work have been translated into Chinese, German, Serbian, Slovenian and Greek. He has also read his work and talked on Australian poetry in throughout Europe as well as in India, Singapore, China, Korea, the United States and New Zealand..jpg)

Maria Takolander’s poetry has been widely published. Her first book of poems, Ghostly Subjects (Salt 2009), was shortlisted for a Queensland Premier’s Literary Award in 2010. She was also winner of the inaugural Australian Book Review Short Story Prize in 2010, and has recently been awarded an Australia Council grant to develop a book of short stories, which will be published by Text. She is a Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies and Creative Writing at Deakin University in Geelong.

Maria Takolander’s poetry has been widely published. Her first book of poems, Ghostly Subjects (Salt 2009), was shortlisted for a Queensland Premier’s Literary Award in 2010. She was also winner of the inaugural Australian Book Review Short Story Prize in 2010, and has recently been awarded an Australia Council grant to develop a book of short stories, which will be published by Text. She is a Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies and Creative Writing at Deakin University in Geelong. Kate Waterhouse is co-editor of Motherlode: Australian Women’s Poetry 1986–2008 (Puncher & Wattmann, 2009). Until 2010, she lived in Sydney with her husband and three young daughters. She is currently living in Auckland, working on her accent and two poetry collections—one set in Australia and one in New Zealand, and on a second editing collaboration with Jennifer Harrison.

Kate Waterhouse is co-editor of Motherlode: Australian Women’s Poetry 1986–2008 (Puncher & Wattmann, 2009). Until 2010, she lived in Sydney with her husband and three young daughters. She is currently living in Auckland, working on her accent and two poetry collections—one set in Australia and one in New Zealand, and on a second editing collaboration with Jennifer Harrison. Nicholas YB Wong is the author of Cities of Sameness (Desperanto, 2012). His poems are forthcoming in Drunken Boat, Gargoyle, J Journal: New Writing on Justice, The Journal, Mead, Nano Fiction, Platte Valley Review, The Portland Review, Quiddity and REAL: Regarding Arts & Letters. He reads poetry for Drunken Boat. Visit him at

Nicholas YB Wong is the author of Cities of Sameness (Desperanto, 2012). His poems are forthcoming in Drunken Boat, Gargoyle, J Journal: New Writing on Justice, The Journal, Mead, Nano Fiction, Platte Valley Review, The Portland Review, Quiddity and REAL: Regarding Arts & Letters. He reads poetry for Drunken Boat. Visit him at  Ivy Alvarez is the author of Mortal (Washington, DC: Red Morning Press, 2006). A recipient of writing residencies from MacDowell Colony (USA), Hawthornden Castle (UK), and Fundacion Valparaiso (Spain), her work is published in journals and anthologies in many countries and online, with individual poems translated into Russian, Spanish, Japanese, and Korean.

Ivy Alvarez is the author of Mortal (Washington, DC: Red Morning Press, 2006). A recipient of writing residencies from MacDowell Colony (USA), Hawthornden Castle (UK), and Fundacion Valparaiso (Spain), her work is published in journals and anthologies in many countries and online, with individual poems translated into Russian, Spanish, Japanese, and Korean.

Misbah Khokhar was born in Karachi-Pakistan, with both European and Indian ancestry. She currently lives in Melbourne. She holds a Masters in Philosophy in Creative Writing from the University of Queensland. Her work appears in Australian Poetry Journal, Cordite, Contemporary Asian Australian Poets and Peril. She has been featured on ABC Radio’s Poetica, and has performed at the Queensland Poetry Festival. She was highly commended by Thomas Shapcott, Brownyn Lea and John Kinsella, and mentioned as a ‘standout’ in Lea’s essay ‘Australian Poetry Now’ (Poetry Magazine, May 2016, Ed. Robert Adamson). Her debut collection Rooftops in Karachi is published with Vagabond deciBels3.

Misbah Khokhar was born in Karachi-Pakistan, with both European and Indian ancestry. She currently lives in Melbourne. She holds a Masters in Philosophy in Creative Writing from the University of Queensland. Her work appears in Australian Poetry Journal, Cordite, Contemporary Asian Australian Poets and Peril. She has been featured on ABC Radio’s Poetica, and has performed at the Queensland Poetry Festival. She was highly commended by Thomas Shapcott, Brownyn Lea and John Kinsella, and mentioned as a ‘standout’ in Lea’s essay ‘Australian Poetry Now’ (Poetry Magazine, May 2016, Ed. Robert Adamson). Her debut collection Rooftops in Karachi is published with Vagabond deciBels3.

Brendan Ryan has had three collections of poetry published, the most recent being A Tight Circle, Whitmore Press, in 2008. His next collection of poetry, Travelling Through the Family, will be published by Hunter Publishers in 2012.

Brendan Ryan has had three collections of poetry published, the most recent being A Tight Circle, Whitmore Press, in 2008. His next collection of poetry, Travelling Through the Family, will be published by Hunter Publishers in 2012. Jen Crawford is a New Zealander living in Singapore. Her poetry collections include Bad Appendix (Titus Books), Napoleon Swings (Soapbox Press) and most recently, Pop Riveter, a set of factory poems available in limited edition from Pania Press. She teaches creative writing at Nanyang Technological University.

Jen Crawford is a New Zealander living in Singapore. Her poetry collections include Bad Appendix (Titus Books), Napoleon Swings (Soapbox Press) and most recently, Pop Riveter, a set of factory poems available in limited edition from Pania Press. She teaches creative writing at Nanyang Technological University. Julie Chevalier’s short-story collection, Permission to Lie, was published by Spineless Wonders in 2011. Two poetry collections are forthcoming from Puncher & Wattmann: linen tough as history, and Darger: his girls.

Julie Chevalier’s short-story collection, Permission to Lie, was published by Spineless Wonders in 2011. Two poetry collections are forthcoming from Puncher & Wattmann: linen tough as history, and Darger: his girls.

Michael Farrell has previously published prose poems in a raiders guide (Giramondo 2008). He coedited (with Jill Jones) Out of the Box: Contemporary Australian Gay and Lesbian Poets (Puncher and Wattmann 2009). His latest publication is thempark (Book Thug 2010). Contact:

Michael Farrell has previously published prose poems in a raiders guide (Giramondo 2008). He coedited (with Jill Jones) Out of the Box: Contemporary Australian Gay and Lesbian Poets (Puncher and Wattmann 2009). His latest publication is thempark (Book Thug 2010). Contact:  Kirby Wright was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii. He is a graduate of Punahou School in Honolulu and the University of California at San Diego. He received his MFA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. Wright has been nominated for two Pushcart Prizes and is a past recipient of the Ann Fields Poetry Prize, the Academy of American Poets Award, The Browning Society Award for Dramatic Monologue, and Arts Council Silicon Valley Fellowships in Poetry and The Novel. BEFORE THE CITY, his first book of poetry, took First Place at the 2003 San Diego Book Awards. Wright is also the author of the companion novels PUNAHOU BLUES and MOLOKA’I NUI AHINA, both set in Hawaii. He was a Visiting Writer at the 2009 International Writers Conference in Hong Kong, where he represented the Pacific Rim region of Hawaii and lectured with poet Gary Snyder. He was a Visiting Writer at the 2010 Martha’s Vineyard Writers Residency in Edgartown, Mass., and also the 2011 Artist in Residence at Milkwood International, Czech Republic.

Kirby Wright was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii. He is a graduate of Punahou School in Honolulu and the University of California at San Diego. He received his MFA in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. Wright has been nominated for two Pushcart Prizes and is a past recipient of the Ann Fields Poetry Prize, the Academy of American Poets Award, The Browning Society Award for Dramatic Monologue, and Arts Council Silicon Valley Fellowships in Poetry and The Novel. BEFORE THE CITY, his first book of poetry, took First Place at the 2003 San Diego Book Awards. Wright is also the author of the companion novels PUNAHOU BLUES and MOLOKA’I NUI AHINA, both set in Hawaii. He was a Visiting Writer at the 2009 International Writers Conference in Hong Kong, where he represented the Pacific Rim region of Hawaii and lectured with poet Gary Snyder. He was a Visiting Writer at the 2010 Martha’s Vineyard Writers Residency in Edgartown, Mass., and also the 2011 Artist in Residence at Milkwood International, Czech Republic. Jill Jones has published six full-length books of poetry, including Dark Bright Doors, which was shortlisted for the 2011 Kenneth Slessor Prize. She co-edited, with Michael Farrell,Out Of the Box: Contemporary Australian Gay and Lesbian Poets. She is a member of the J. M. Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice at the University of Adelaide.

Jill Jones has published six full-length books of poetry, including Dark Bright Doors, which was shortlisted for the 2011 Kenneth Slessor Prize. She co-edited, with Michael Farrell,Out Of the Box: Contemporary Australian Gay and Lesbian Poets. She is a member of the J. M. Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice at the University of Adelaide. Ivy Ireland is a part-time cabaret performer, creative writing tutor, harpist, magician’s assistant, and PhD candidate. Ivy was awarded the 2007 Australian Young Poet Fellowship, and has had her poems published in various literary magazines and anthologies. Ivy’s first solo poetry publication came out in 2007 and is entitled Incidental Complications.

Ivy Ireland is a part-time cabaret performer, creative writing tutor, harpist, magician’s assistant, and PhD candidate. Ivy was awarded the 2007 Australian Young Poet Fellowship, and has had her poems published in various literary magazines and anthologies. Ivy’s first solo poetry publication came out in 2007 and is entitled Incidental Complications. Suneeta Peres da Costa is an award-winning writer whose work includes the bestselling novel Homework (Bloomsbury), stories, essays, and poems in local and international journals and anthologies, as well as numerous productions for ABC Radio. The pieces that appear here are taken from a collection of short, experimental fiction. She currently lives in Sydney.

Suneeta Peres da Costa is an award-winning writer whose work includes the bestselling novel Homework (Bloomsbury), stories, essays, and poems in local and international journals and anthologies, as well as numerous productions for ABC Radio. The pieces that appear here are taken from a collection of short, experimental fiction. She currently lives in Sydney. Jaimie Gusman lives in Honolulu where she is a PhD candidate at the University of Hawaii, teaches creative writing and composition, and runs the M.I.A. Art & Literary Series (

Jaimie Gusman lives in Honolulu where she is a PhD candidate at the University of Hawaii, teaches creative writing and composition, and runs the M.I.A. Art & Literary Series (

.jpg) Stu Hatton is a Melbourne-based poet who keeps himself out of trouble by working on

Stu Hatton is a Melbourne-based poet who keeps himself out of trouble by working on