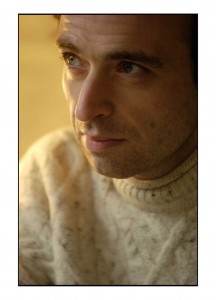

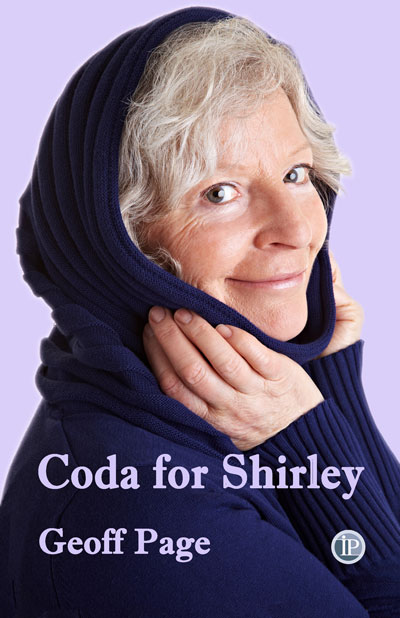

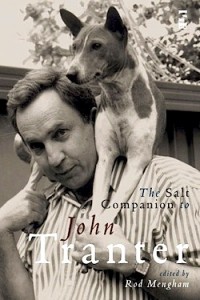

John Tranter has published more than twenty collections of verse, and has edited six anthologies, including The Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry (with Philip Mead). He studied for and received a Doctorate of Creative Arts from the University of Wollongong and is an Honorary Associate in the University of Sydney School of Letters, Arts and Media, and an honorary fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. He has given more than a hundred readings and talks in various cities around the world. He founded the free Internet magazine Jacket in 1997 and granted it to the University of Pennsylvania in 2010. He is the founder of the Australian Poetry Library at http://poetrylibrary.edu.au/ which publishes over 40,000 Australian poems online, and he has a Journal at johntranter.net and a detailed homepage at johntranter.com.

Photograph: John Tranter, Cambridge, 2001, by Karlien van den Beukel.

Toby Fitch was born in London and raised in Sydney. His first full-length collection

of poems Rawshock was published by Puncher & Wattmann in 2012. He was shortlisted

for the Peter Porter Poetry Prize 2012 and has published poems in anthologies, newspapers

and major journals, nationally and internationally, including Best Australian Poems2011

and 2012, Meanjin, The Australian, Cordite, and Drunken Boat. He is poetry reviews editor

for Southerly journal, and is a doctoral candidate at Sydney University.

http://tobyfitch.blogspot.com

Toby Fitch: Let’s start by talking about your most recent collection of poems,

Starlight: 150 Poems (University of Queensland Press: 2010), which to me

presents the culmination of a number of text-generating techniques in your poetry.

For the 83 poems in the second section of Starlight, ‘Speaking French’,

you created these by reading poems by Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine,

Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé into a speech-to-text computer program,

reading the poems in French, though the computer program only had an English

dictionary. The computer then spat out an initial kind of mistranslation that

provided you with a completely new set of words, sounds and phrases to shape

into your own poems. How did you sift through and choose what to use from the

texts that were spat out by the computer?

John Tranter: The speech-to-text program produced a page or two of prose

in each case, mainly gibberish. I worked through each piece throwing out things

that didn’t seem to fit, and moving pieces of text around until some kind of narrative

emerged. I did a lot of rewriting, until I had about a page of reworked writing.

Fitch: Did the speech-to-text program pick up much of the original French

and the original writers’ concerns?

Tranter: No, what it produced was almost totally different. It only ‘understood’

American English, and it was tinted with contemporary Americanisms, naturally

enough: CIA, CD, spreadsheet, voting, market, company, fax, and so on, phrases

you would be likely to find in a letter dictated by a business manager in

contemporary America – which was the target audience and purpose for the program

– a lingo I sometimes played riffs on. It’s interesting how often ‘CIA’ occurs, for

example. Those phrases don’t occur in the originals!

Fitch: Of course not. What made you structure these mistranslations as sonnets,

as opposed to writing them in freer forms, or with no prescribed line count?

Tranter: Perhaps my passion for neatness. At some point I saw that these drafts

could be turned into fourteen-line poems, give or take a few lines, so I turned them

all into sonnets.

Fitch: Writers often start to write a sonnet planning that it will be a sonnet, from

the start. Had you ever done any of this kind of thing before, just turning a whole heap

of different short poems into sonnets? Was this how your early book Crying in Early

Infancy: 100 Sonnets came about?

Tranter: Yes, that’s more or less what I did with the forty or so short pieces of poems

that I brought back from Singapore in the early 1970s. I lived in Brisbane from 1975

to 1977, and Martin Duwell (who also lived there) asked if I had a book manuscript he

could publish. He had already published my chapbook The Blast Area in 1974 as

number 12 of the Gargoyle Poets series. There are quite a few fourteen-line poems in

The Blast Area too.

I thought about what I had lying around, and proposed a book of one hundred sonnets,

and worked on those forty short poems until that is what I had to give him, which

became the book Crying in Early Infancy: 100 Sonnets (Makar Press, St Lucia, 1977).

I asked Martin to choose an order for the poems, as I couldn’t see much pattern in them.

Most of those ‘sonnets’ are not rhymed.

Fitch: A lot of readers might feel that much modern poetry is kind of formless. But the

sonnet form is quite old, older than Shakespeare, and most sonnets are very intricately

structured. Is it the sonnet’s neatness that appeals to you?

Tranter: You’re right. I do seem to have a psychological need to make things look tidy;

to clean up the kitchen, which I do first thing every day, to do the washing up and the

washing, to iron a creased shirt. With me, I guess it has something to do with growing up

on a farm. I like tractors, and learned to drive one at age ten or twelve – and with a tractor

you turn a paddock full of old dead plants and weeds into something ploughed into neat

rows and sown with shiny new plants – say peas or beans – then you harvest them, sell

them, and make some money. There’s a process there: you work at transforming

something wild and chaotic into something neat and ordered, and if you’re lucky, you

make a living. That process is older than capitalism: it began with agriculture, tens of

thousands of years ago. Except we now add fertiliser, made from mountains of bird shit

in Nauru.

And that’s how poetry works: you turn the jungle and chaos of talk and speech and action

and history into ordered lines of verse, neatly set up with rhyme and stock epithets to be

memorised and reproduced, over and over again. The incoherent mess of physical and

emotional experience is transformed into literature: stories that have (an artificial) shape,

pattern and meaning.

I was talking about these more recent French-derived poems in Starlight with poet

and radio producer Robyn Ravlich for an ABC radio program a year or so ago, and

mentioned that some critics had objected to my calling the Crying poems sonnets,

because they lacked rhyme (well, some of them had rhyme, but none of these so-called

critics noticed or mentioned that.) ‘Perhaps I should call these new ones Nonnets,’ I said:

‘Non-rhymed sonnets.’ Robyn quite properly reminded me that the word Nonnets was

already taken: for nine-line sonnets. ‘Okay,’ I said, ‘Let’s call them Ronnettes:

Rhyme-Free Sonnets’. So that’s what these poems are, Ronnettes. (I also like the vocal

group of that name, a big-hair 1960s girl group from New York City produced by Phil

Spector: they had some really big hits.)

Fitch: Yeah, so they don’t use rhyme, but they are divided into eight and six-line

stanzas. What other organising principles are at work?

Tranter: I had the idea of linking them somehow to John Ashbery, a friend and

long-term influence on my work. The poems were originally written as part of a Doctor

of Creative Arts thesis at the University of Wollongong, and one of the purposes of the

arguments buried within the thesis is the influence on my writing of the poetry and lives

of Arthur Rimbaud, ‘Ern Malley’ and John Ashbery, who, as it happens, are linked in

other ways too.

So I read through Ashbery again and selected a hundred or so lines and phrases from

his work that I liked, and took each fragment and wove it into the fabric of each of the

hundred or so ‘Ronnette’ poems I had written. Well, there were over a hundred,

originally. I dropped many of the less successful poems for the book publication. So if

you have read all of John Ashbery and have a good memory, as you read through my

‘Ronnettes’ little flashes of recognition will occur to you and will help to make your day

more varied and interesting.

Fitch: What was your criteria for choosing certain Ashbery lines, how and where in the

poems did you decide to splice them in, and did all the Ashbery lines survive the editing

process?

Tranter: I chose the lines I liked, that seemed striking or strange or original. It was just

a matter of personal taste, really, or perhaps whim. And I looked to match the concerns

of the Ashbery lines with what my poems seemed to be about; or perhaps contrast them,

depending on my mood at the time. If a poem mentioned the seasons, I inserted an

Ashbery line about the seasons or the weather; if a poem contained a line like ‘You will

find, in that vista, all you could have been’, say, I would add this Ashbery line (about a

vista) just ahead of it: ‘From where I sit I can see hundreds of freight cars.’ Here are some

of the Ashbery lines I used, together with the poems they appear in – you’ll see I thought

of dropping some, though I can’t remember why – perhaps the poems they were in failed

to work:

Men appear, but they live in boxes. / Rimbaud: Shames

Behind the steering wheel / Rimbaud: Story

Turn on the light / Rimbaud: Departure

Advancing into mountain light / Rimbaud: Villas

It’s true we have not avoided our destiny / Mallarmé: Wild Swine…

The distant box is open / Rimbaud: The Fixer

But hungers are just another topic / Rimbaud: Genius

You who were always in the way / Rimbaud: Pronto

To tell the truth the air turned to smoke / Mallarmé: Bracket Creep

There was calm rapture in the way she spoke / Rimbaud: Bottom of the Harbour

Performing for thousands of people / Rimbaud: Childhood

the vineyards whose wine tasted of the forest floor / Rimbaud: Winter Maps

There is no possibility of change / Rimbaud: Flowers

I prefer ‘you’ in the plural / Mallarmé: Whistle While You Work

The whole voyage will have to be cancelled. / Rimbaud: Horticulture

Silly girls your heads full of boys. / Rimbaud: Movements

Barely tolerated, living on the margin / Rimbaud: Lives

This was our ambition: to be small and clear and free / Rimbaud: Martian Movie

night after night this message returns / Rimbaud: New Beauty

but the fantasy makes it ours / Rimbaud: Marinara DROPPED??

the promise of learning is a delusion / Rimbaud: Metro

It was raining in the capital / Rimbaud: Phrases DROPPED?

she thought she had seen all this before / Rimbaud: Tenure Track DROPPED?

you are the harvest and not the reaper / Rimbaud: Ornery

the presumed landscape and the dream of home / Rimbaud: Parade

Fitch: Did some Ashbery lines get subsumed into your writing so much that you

forgot which ones were yours and which were his?

Tranter: Oh yes. In fact I was disappointed to discover, on reading through the

poems months later, that some very clever lines that I had grown to assume were mine,

in fact had been borrowed from Ashbery, whose cleverness is more effortless and

abundant than my own. And vice versa, perhaps: when John read the collection he

said ‘Some of its lines felt as though I wrote them.’ He has a very dry sense of humour.

Fitch: The issues of influence are very important to your poetics. Can you talk

about the influence of Arthur Rimbaud on you and on your attitudes towards writing?

Tranter: Sure: it was an early influence, and felt important to me. I have already

talked about that at length in my long poem ‘Rimbaud and the Modernist Heresy’

and in book reviews and interviews: I suggest the interested reader search Google

for ‘Tranter’ and ‘Rimbaud’. Kate Fagan and Peter Minter have a very clever essay

on the topic in Jacket magazine (1) which is also published in Rod Mengham’s

Companion to John Tranter book from Salt Publishing in the UK. (2)

Fitch: Yes, that’s a fascinating essay which reads your poetry as having, via Edward

Said, a kind of ‘“Orientalising” force in Australian poetic reflections on the European

and… the American’, i.e. an ‘otherness’.

Tranter: To me, Rimbaud, being French (culturally distant) and historically distant,

was always strange and very ‘other’.

Fitch: Of course, Rimbaud made it to Java during his travels after giving up poetry…

Tranter: Yes, he travelled obsessively, often by walking. He was what the French call

a Fugueur’.(3) After he gave up poetry around 1873 he visited seventeen countries and

travelled more than fifty thousand miles. In many ways his life after 1873 was more

varied, strange and interesting than the rather predictable earlier career of the

smart-arse gay poet in Paris in his late teens.

Fitch: One of his biographers, Graham Robb, even suggests he might have made it to

Darwin.

Tranter: I think that’s quite possible. In fact – well, let’s backtrack a little. When I met

Sidney Nolan over dinner at Manning Clark’s place in Canberra in the late 1980s I was

alarmed by Nolan’s story about his visiting the Rimbaud museum in Charleville, in

northern France – decades before. In a margin of Rimbaud’s diary, or perhaps

notebook, Nolan said, someone – probably Rimbaud – had pencilled the words

‘Wagga Wagga’. Of course he could have visited Wagga Wagga in 1876, between

deserting from the Dutch army in Java and returning to Europe some months later,

but to any reasonable mind, the evidence is against it. Years ago I searched the Wagga

Wagga Advertiser for clues as to the presence of a young Frenchman there in the

latter half of that year, but alas, the search has been fruitless. So far.

Fitch: I think the pencilled words might actually have been “Wagga Wagga berry”

(see footnote on p.283 of Robb’s biography), which I guess Rimbaud could have tasted

at some stage in Darwin, or anywhere really, if such a berry exists.

Though, there’s also a Berry Street in Wagga Wagga…

Tranter: That’s odd. The main newspaper in Wagga Wagga for over a century has been

the Wagga Wagga Advertiser. Frank Moorhouse, the Australian novelist, worked on

that paper as a journalist in the early 1960s. His great novel trilogy is based on the life

of an Australian woman diplomat named Edith Campbell Berry, probably named after

a town called Berry, near where Frank grew up, in the town of Nowra, on the south coast

of New South Wales.

Fitch: Like Rimbaud, you became disillusioned with poetry at a young age, travelling

in the late 1960s/ early 1970s to live in Singapore, but then you returned to Australia.

Can you tell me a little more about the ‘otherness’ of your work, and how that might

have sprung from your early disillusionment?

Tranter: When I left Sydney for Europe in 1966, it was partly to see the world, but also

partly to get out of Australia, which was suffocatingly dull and hideously authoritarian

in those days. No one under fifty can imagine how bad it was: petty rules and regulations

everywhere, censorship, police corruption and thuggery; it went on and on. So if that

was normal, I wanted something ‘other’. Anyhow, I returned to Sydney in 1967 and

eventually finished a degree.

Being posted to Singapore as Senior Education Editor for Angus and Robertson in 1971

– they had been a major publisher, especially of poetry, for a century, believe it or not

– presented a wonderful opportunity to experience a very different culture. (I’m looking

forward to visiting Singapore again for the Singapore Writers Festival in November 2012.)

The variety of food was and still is wonderful; but the culture of Singapore in those days

was very repressive. They even forced you to cut your hair short by making you go to

the end of every line (waiting at a bank, or shop) if your hair was long. Visitors with long

hair were not allowed to disembark from their plane. And so on. Needless to say I had

frequent haircuts.

At one time when I had rather long hair, and I was followed by a gang of children

calling out ‘Charlie Manson your Leader! Charlie Manson your Leader!’ That was

the level of debate.

While I was there from 1971 to 1973 I read lots of novels, and no poetry. But this

distaste for the artificiality of poetry occurred every eleven or so years, I eventually

realised. Much later I asked a psychiatrist how that could be, when there was no natural

or social phenomenon which occurred in eleven-year cycles. ‘Oh, there is one,’ he

replied. ‘Sunspots’. Well, that floored me. I don’t believe in the effect of sunspots on

human behaviour, but it looks as though I may have to.

Fitch: My crises, for want of a better word, tend to happen every three to four years,

though I think of them more as flips of a magnetic field, like a reversal of the north and

south pole (which I guess is relatable to the sun). When was the last, most recent,

sunspot for you? Did it happen before Starlight:150 Poems, or around the time you

published your Urban Myths: 210 Poems: New and Selected, in 2006?

Tranter: I should look it up. Uh… 2005, according to my Maniac’s Almanac. What was

I doing in 2005? Not much. I finished ‘Urban Myths’. I had failed to obtain a grant

from the Literature Board, which was not uncommon. I had failed to obtain a grant

from the University of New South Wales, but then I always have. I was pretty miserable,

as usual. (Don’t be a poet!) I think any distaste I felt was for the people who inhabit

the world of literary bureaucracy as public servants or ‘advisors’. I was soon to enrol for

my doctoral degree at the University of Wollongong, which was fun. I had the good luck

(or good sense) to end up with John Hawke as my supervisor. He was immensely helpful.

Fitch: Your mistranslations of Rimbaud’s poems from Illuminations aren’t at all an

act of copying, but could your mistranslations be considered a postmodern contribution

to the long tradition of artists painting studies (or writing versions) of their favourite

artists’ works?

Tranter: Oh yes, indeed they could. I’m conscious of that long tradition, and of my

place within it. I think that is how any artist learns her or his craft. The Australian poet,

Robert Adamson, talked about his experiences with that process to me once, in an

interview we did in 1978 for Makar magazine. (Reprinted in A Possible Contemporary

Poetry. St. Lucia, Qld. : Makar Press, c1982. 160 p., and available on the Internet at

http://johntranter.com/interviewer/adamson1978.shtml).

It’s common in graphic design, in typography, in painting (Bacon on Velázquez, Picasso

on Velázquez) and in music (think of Bach’s ‘Goldberg Variations’ or Beethoven’s

‘Diabelli Variations’) as well as in literature. With Shakespeare, his every storyline was

borrowed from some other writer.

Perhaps it is not talked about so much in writing these days, because writers are often

nervous of accusations of plagiarism, and then there’s the morass of hoax and fakery

to make one self-conscious.

Fitch: Do you still get excited when you read early modernist poetry, specifically

the French?

Tranter: Perhaps ‘getting excited’ is what you expect from drugs or sex. With writing,

at least at my age, it’s more a kind of quiet glow. Yes, those writers from Baudelaire

to the mid twentieth century European poets faced up to the modern world with some

extraordinary creations; you see it in music too in Fauré and Debussy and others, and

in art with Impressionism.

These artists were there on the ground when the Industrial Revolution, the French

Revolution, the Napoleonic Revolution, the Scientific Revolution, the Socialist

Revolution and the Romantic Revolution all crashed head-first into the modern world

one after the other in slow motion, all of which took most of the nineteenth century

to work out. The French Revolution occurred over the decade 1789 to 1799, the fax

machine was patented in 1848; Baudelaire’s day (1821–1867) saw the steam

train, photography and the telegraph revolutionise all the world.

I was delighted to discover an obsession with those inventions (and with the telephone

system and automobiles and airplanes) in Proust’s later autobiographical novel, looking

back over his youth, from the early twentieth century.

Fitch: All that machinery…

Tranter: Yes, first tractors, then Proust. Like Auden, I find machinery interesting; as

much so as I do literature. What did he write? When Auden was nearly thirty he wrote

“Tramlines and slagheaps, pieces of machinery, / That was, and still is, my ideal

scenery.” Gosh, what a clunky dactyllic rhyme. Rimbaud’s friend and fellow-poet Charles

Cros (they worked in a cardboard-box factory in London together) invented the

gramophone and demonstrated his device before the French Academy in 1877, four

months before Edison demonstrated his machine, but Edison (not a dreamy poet, an

American entrepreur!) was the first to take out a patent. So poets and machinery can go

together.

Fitch: Can you speak French? Can you speak pig Latin? Can you speak in HTML?

What role does the multi-lingual have in your poetry, and do you think there are enough

dealings with other languages in contemporary Australian poetics?

Tranter: Just English. I have always felt that Australians are lucky to have the English

language, with its extraordinary reach and complexity, most of which comes from the

cross-fertilisation with other languages, because of Britain having been invaded and

conquered by the Celts in 600 BC, by the Romans in 43BC, by the Anglo-Saxons in AD

450, by the Vikings in 793, by the Norman French in 1066 and by the Dutch under

William of Orange in 1688. The last is often overlooked, but it was a massive invasion

of 53 warships bristling with 1,700 cannon,which fortunately was not resisted and in

many cases welcomed, at least by those of a Protestant persuasion.

Other languages are interesting, but I don’t feel they are necessary. But that may just be

me justifying my own shameful limitations. I can speak enough poor French to find

myself in serious trouble in a restaurant. Latin, no; my daughter learned Latin

(thoroughly) one summer in New York. I’m veryimpressed by that.

I went to school in a little country town, where no one taught any languages. It was felt

that Australian farmers didn’t really need French, for example. It’s hard to argue with

that view. I had never heard anyone speak anything but Australian until I was an adult.

What a shame!

Fitch: I guess you hardly need French to talk to pigs. What about the complications

of publishing on the Internet? Did you have to learn that language?

Tranter: Yes, but I was lucky. I had learned a computerised typesetting code that was

more or less the same as HTML when I helped my wife Lyn to run a typesetting

business in the late 1970s. So when I taught myself HTML and Cascading Style Sheets

from books, in the late 1990s, it felt fairly easy. I wanted to make Jacket magazine

(1997–2010) look attractive and also pleasant to use: that is, easy to navigate, so I felt

I should learn all that stuff.

Fitch: Back to those versions of other writers: why did you choose to write

mistranslations and versions of these particularly well-known French poets? Why not

choose more obscure poets? Is it to do with access to the original foreign-language

poems, i.e. so that a reader can compare your version to the blueprint of the original

poem, or is it to do with something else altogether?

Tranter: Partly the public access, and the comparison, yes. Martin Duwell

has a good account of my poem ‘Rotten Luck’ in a review of Starlight: ‘This is not only

a better, tighter, and more intense poem than Baudelaire’s “Le Guignon”, it makes a

point of transforming its original humorously.’ What a kind reviewer!

The distance between Baudelaire, say, and one of my ‘versions’ of his work, is really the

150-year gap between 1860 and 2010. We can never really recapture what it felt like for

Charles Baudelaire to go for a walk in the Paris of 1860. We can take the same walk today,

but everything is different, even the street map, the pavements (less cobblestones for

people to throw at police, and that’s not an accident), and the shoes. And then there’s

what Paris went through in two World Wars, which Baudelaire could not have imagined

in his worst nightmares.

He didn’t even live to see the first of the three great German-French wars, the Franco

-Prussian war of 1871, when the Germans practiced invading the rest of Europe.

Rimbaud saw it up close: it ploughed across his backyard in Charleville. Once the railways

were properly set up, the Germans did it in earnest in 1914. And by 1939 they didn’t need

the railways, really. They had Panzer tanks and a good air force.

But to be honest, the original material is not important, and anyway it’s so mangled

when I finish with it that it’s only my literary savoir-faire that can turn the sow’s ear

into the silk purse that my readers demand. So perhaps the whole process is merely

a meal for my ego.

Fitch: Have you used computers for composing other creative writing texts

before this?

Tranter: Yes, on and off for decades. For example, I compiled a book of seven prose

texts titled Different Hands back in 1998. They are all blends of two different original

works. As an example, one of them,‘Room With a View, Spa Bath, Many Extras’ is

derived from the computerised blending of part of the extremely literary novel Room

With a View by E.M. Forster, and advertisements for properties for sale in Sydney’s

Eastern suburbs, hardly a literary source at all. From that linguistic domain we have

the phrase ‘deceptively spacious’, one of the great non-sequiturs of modern English.

So it really is a blend of different registers. But the point of those pieces was to start

with something deliberately lacking in meaning, and by dint of much hard work to

drag it in the direction of meaning.

Fitch: You’ve provided extensive notes on your website for all the poems of Starlight.

Some poets who write versions or mistranslations don’t provide any notes whatsoever.

Tranter: Maybe they want to hide where their inspiration really comes from!

Fitch: ‘Inspiration’ doesn’t sound like a word used in relation to text-generating

poetics, or is it just unfashionable at present to use that word for fear of its alignment

with the Romantic?

Tranter: I’m too old to fear much. To me ‘inspiration’ is not so much a gift of breath

from the gods of verse, but more like the kind of mental spark that might occur to a

biochemist or a mathematician: a kind of ‘Eureka!’ moment where a possible solution

to a problem leaps into the mind.

When some writers use text-generating techniques, they let the computer construct

the text and leave it at that, as they lack any fresh ideas about dealing with the new

material, or perhaps they just lack confidence in their own talents, or perhaps they

have been told that any emphasis on the ‘I’ in a poem is naughty and discredited and

thus they fear to intervene.

Edgar Degas was discussing poetry with Mallarmé; ‘It isn’t ideas I’m short of… I’ve got

too many’ [Ce ne sont pas les idées qui me manquent… J’en ai trop], said Degas.

‘But Degas,’ replied Mallarmé, ‘you can’t make a poem with ideas. … You make it with

words.’ [Mais, Degas, ce n’est point avec des idées que l’on fait des vers. . . . C’est avec

des mots.] (From Degas, Manet, Morisot by Paul Valéry (trans. David Paul), Princeton

University Press, 1960.)

Fitch: Some of your notes were part of your doctoral thesis, so they have an academic

purpose, but what are their importance to more general readers of your work? Do notes

limit the possible readings of a poem, or do notes provide extra layers for possible

readings? You seem to have used them a lot, over the years.

Tranter: I like notes, true. Perhaps too much. A story I like, by J.G. Ballard, consists

only of condensed notes: the detailed and richly complex Index to a non-existent novel.

The reader has the very creative task of rebuilding the story of the novel from the strange

(and often humorous) clues in the Index. The story is titled ‘The Index’, and was written in

1977 and published in The Paris Review, volume 118, (Northern) Spring, 1991.

Of course the novel of ‘The Index’ that you reinvent in your mind is different for every

reader, and each reader is joining in with the writer to create it.

But the notes are meant to provide extensions to the text, like hair extensions, I guess,

not limits. I don’t like to limit how my readers understand my poetry. I have always felt

that a poem belongs to the reader, and they can do what they like with it. With my book

of narrative poems The Floor of Heaven, written in the 1980s and sometimes set as a

Higher School Certificate recommended text for study, a school pupil called Olivia T

wrote to me just this year with the suggestion that a particular character in one of the

interlinked poems, Sandra, was really the un-named narrator in one of the other poems

titled ‘Gloria’. I hadn’t thought of that, in all of the quarter century that has passed since

I wrote it, but it’s a very clever suggestion, and it’s probably true. I thanked her.

The Spanish anarchist film director Luis Buñuel said in the 1950s that films work in

the same way as dreams; and I believe that poems work in that way too. And often

someone else (a trained therapist, say) can understand your dreams better than you can,

because dreams are often disguised specifically to prevent you from seeing just what

they mean. Sometimes other people can see through that disguise, as they don’t need

to have those truths hidden from their conscious minds.

Fitch: I think you mentioned Buñuel and that quote, and the idea that poems work

like dreams, in the Introduction to the anthology The Best Australian Poems 2011, which

you compiled. Do all poems have to work like dreams?

Tranter: You’re quite right, and as well I drew all those ideas from my doctoral thesis.

And no, poems don’t all have to work like dreams. Of course not. In fact in my Introduction

to this year’s Best Australian Poems 2012 anthology I state the opposite, by showing that

most of the poems I chose have stories to tell, and work like brief narratives or condensed

stories. They don’t work like dreams at all. But then, most dreams and most movies are

built on narratives, however distorted. So I guess I can have my cake and eat it too.

Fitch: Talking of Buñuel, you seem to love movies. Many of your poems in previous

books mention movies, or deal with images or scenes from movies in interesting ways.

Can you say a little bit more about the relationship between cinema, i.e. the moving picture,

and poetry? The section of poems in Starlight called ‘At the Movies’ is placed between two

other sections of poems that outlay different modes of translation, as discussed above.

What can you say about the ‘translation’ of cinematic scenes, characters, and images,

into poems?

Tranter: I do love movies. They give you thousands of different universes to explore,

each one like a different dreamscape. In fact the book of narrative poems I mentioned,

The Floor of Heaven, was inspired by Buñuel’s 1972 movie, The Discreet Charm of the

Bourgeoisie, where the plot is driven entirely by people recounting their dreams.

When I was a boy, growing up on a remote farm in 1950s Australia, the big event of the

week for me was Friday night at the local town cinema. The feature movie represented

everything foreign and dramatic and wonderful. Cinema had a magic glow that the

everyday world lacked. People actually drank cocktails, in the movies. I had never seen

a real person drink anything but beer or sherry. Perhaps that was the beginning of my

liking for martinis.

Also, basing a poem on a movie is a kind of translation: the movie exists in its own

world, a world qualified by the entertainment economy, by machinery, chemistry,

technology, acting talent, writing talent, and directing talent. Taking the movie out of

that world and inserting it into the world of poetry is a little like updating Beowulf into

a Western movie plot (Ronald Reagan as Beowulf, ) or like blending Freudian theory

and Shakespeare’s The Tempest into a science-fiction movie, which is how the 1956

movie ‘The Forbidden Planet’ works.

A poem about a movie can be a kind of film review; or it can be a kind of remake of the

movie, or it can be a social or political critique of the conventions that appear in the

movie.

Talking of remakes, did you know that the famous Bogart movie vehicle The Maltese

Falcon was in fact the third movie based on Hammett’s story? What happened to the

other two? What gave the third version, with its identical plot, its special magic?

The direction (it was the first movie John Huston had directed)? The acting?

The moody lighting?

Fitch: Maybe it wasn’t the right time, when the first two came out. Maybe people

weren’t ready till the third.

Tranter: Perhaps you’re right. I believe the second one was a rather feeble comedy,

believe it or not.

Fitch: Speaking of timing, who would you rather date: Kim Novak, Lauren Bacall,

and Dorothy Gale, each of whom make an appearance in your ‘At the Movies’ poems?

Tranter: Wow. I feel Lauren Bacall would eat a man like me for breakfast, so no to that

one. And no, I don’t think I could be a friend of Dorothy Gale, cleverly named after the

tornado that swept her over the rainbow into the Land of Oz. Her role was acted by

Judy Garland, a woman I never liked that much. But when I was thirteen, my hormones

just beginning to cause trouble, I saw Kim Novak in the movie _Picnic. She seemed like

a beautiful, innocent goddess to me. And then in Vertigo… goddess again. I wanted to

marry her. So Kim, definitely.

Though decades later I read an interview with a much older Kim Novak where she

talked about how wonderful trees are: ‘For one thing, I’ve always admired trees.

I just worship them. Think what trees have witnessed, what history, such as living

through the Civil War, yet they still survive.’ Ouch!

Fitch: So what other painful ordering techniques do you employ to write other poems,

not sonnets?

Tranter: Dozens; everything I can think of. But the reader shouldn’t have to suffer;

let the writer do that! There’s rhyme, of course, though I prefer half-rhyme and

alliteration. Making your end-words rhyme is one device; repeating them unrhymed in

a varied order is what makes the sestina so strange and interesting. To take that one step

further, I like to take a poem by some other writer and use the end-words in a different

poem of my own; I call that device ‘terminals’. Brian Henry has a detailed explication

of the technique on my web site.

A Chinese-born woman journalist was interviewing me recently and I described how

I took end words from other poets’ work. She looked frightened. ‘But are you allowed

to do that?’ she asked.

Fitch: And here’s a kind of super-terminal: the 253-line opening poem of Starlight

uses the first and also the last couple of words of each line of John Ashbery’s poem

‘Clepsydra’ as a scaffolding technique, and then you’ve filled in the middle of each line

to write your own poem, ‘The Anaglyph’ (one can read about what an anaglyph is, and

about the process of writing your poem here:

http://johntranter.com/notes/starlight.shtml#notes). By the way, was Ashbery

annoyed by your stealing his end words and rewriting his poem?

Tranter: Oh no, I asked – I didn’t want to offend him – and he gave me permission to

do that. I think he liked the idea.

Fitch: You’ve described the process of writing ‘terminals’ as ‘replacing the meat in the

sandwich’, which struck me as a rather masculine way of thinking about it.

Tranter: Maybe so, but I think it’s a pretty good image. The starting word and the ending

word of each line, from Mr Ashbery, are like the two slices of bread; my filling is like the

filling. I saw the process as being like turning a ham sandwich into a turkey sandwich. Not

that John’s a ham, or I’m a turkey! And, for my first fifteen years, my mother always made

the sandwiches for my school lunch, so I have always seen that as a feminine act. But I’m

wandering… go on…

Fitch: (I was thinking of the sexual innuendo, sorry… but you don’t need to answer that

if you don’t want to). The poem itself puts it more neatly, I guess: ‘like gutting then

refurbishing a friend’s apartment.’ Why do all these apartments, i.e. the poems of Ashbery,

Rimbaud, Baudelaire, etc. that you’ve reworked, belong to men? (I don’t mean ‘apartments’,

literally…) I like to think of them as poetic theme parks.

Tranter: That’s a good metaphor. With John Ashbery’s apartment, John happens to

be a male. And with the line about ‘refurbishing a friend’s apartment’, I was probably

thinking about those television shows where someone redecorates a friend’s apartment as

a surprise. Well, everyone pretends it’s a surprise.

And it is true that most of the strong influences on my work have been male poets, but

then I think male poets make up a vast majority of the most influential poets in history, from

Homer to Frank O’Hara, and you can hardly pretend otherwise.

Though there are dozens of women poets whose work I like, from Sappho to Emily

Dickinson to Elizabeth Bishop to a whole bevy of younger US American women writers,

too many to name. (Now ‘bevy’ is a nice collective noun.) Many younger Australian

poets are women, perhaps more than men.

I’m currently writing a ‘Commentaries’ blog for Jacket2 magazine in Philadelphia, and

I am delighted that the editor I deal with there is a woman, Jessica Lowenthal. My first

book was published by a woman. I set up a small press and published four poetry books

in the early 1980s: Gig Ryan’s first book, Susan Hampton’s first book, and books by John

Forbes and Alan Jefferies. And the Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry, which I

edited with Philip Mead, was commissioned for Penguin by Susan Ryan. It contained a

higher proportion of women poets than any general anthology of Australian poetry had,

up to that time.

Fitch: Have gender politics influenced your methodology and your poetics over the years?

Tranter: I guess I have always had a supportive attitude to feminism, but that’s more

instinctual than politically informed. My mother, her sisters, and her own mother were

strong women whom I respected, and I was always aware that they should each have been

able to make more of their own intellectual lives, particularly my grandmother. She should

have gone on to university, but the expectation of the times – this was around 1890 – and

her role as a mother of a series of children constrained her. They all felt bound by

society’s expectations to be just a woman, a mother, a supporter of men. Though my Aunt

Barbara became a trained schoolteacher, just as my father did.

And though I generally support feminist thinking, like any good philosophy, it can be

taken too far. Decades ago I worked with a woman with strong feminist views who

insisted that in a job application situation, given two applicants – a man with the exact

talents and skills to do well at the job, and a woman who just happened to be incompetent

in that field – that the job must be given to the woman, because women have been

downtrodden for so long by men. That attitude is a recipe for feather bedding corruption

and the rewarding of incompetence, but that does happen. Even in the world of writing,

unfortunately.

Fitch: You mentioned the high proportion of women poets in the Penguin Book of

Modern Australian Poetry. What about the recent Thirty Australian Poets, edited

by Felicity Plunkett, which has more women in it than men?

Tranter: It’s good to see things changing. When I reviewed that book in The Australian

I wrote ‘though editor Felicity Plunkett doesn’t go on about it, 60 per cent are female,

making this the first general anthology of Australian poetry with fewer men than women

in its pages. This mocks Les Murray’s 1968 remark in American Poetry Review that

“women are writing less well because feminism is there to absorb the energies that

otherwise would have gone into literature”. This myth was always a self-serving untruth

and this collection shows feminism empowered women to write poetry — and more and

better poetry than that written by men, in many cases.’

Fitch: In an earlier anthology of yours in 1979, ‘The New Australian Poetry: the work

of twenty-four poets from Australian poetry’s most exciting decade’, you included your

own poems and you coined the term ‘Generation of ’68’, referring to a certain group of

Australian poets who emerged around 1968 and who had an eye on the progressive

developments of American poets of the 1950s and 1960s. The term is now used quite

widely in current anthologies and reviews, and a number of other poets of the 1970s

are being lumped in with this generation, for convenience I guess, who aren’t necessarily

happy to be defined as such. What was your intention when you coined this term? Did

you realise at the time the extent to which it would mark out a generation?

Tranter: Yes, I included my own poems. I could hardly pretend that they were not

relevant to the topic, and the anthology was a deliberately polemical one, not like later

more general anthologies I compiled. And no, I didn’t realise then how the phrase fitted

so well to a journalistic view of culture. Nobody was happy to be labelled like that, and

very few were happy to be in the book, even though it brought their writing to thousands

of new readers.

When I mentioned to Tom Shapcott, who had edited a few anthologies, that I was about

to compile an anthology, he suggested that in his experience I would lose all my friends.

But why? I asked. Surely those whose work I include will be pleased?

Silly me. He laughed, and explained that those I left out would hate me, and those I

included would hate me because I had not chosen their best poems, because I had put

their work next to X–- whom they hated, and because I had not included their best

friends Y–- or Z–- . And in any case, why hadn’t the publisher asked them to compile

the anthology? I’m remembering this from the mid 1970s. Sadly he was right.

You don’t believe me? When I told my friend John Forbes I had been chosen to edit the

Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry, which I thought would be wonderful news

– wasn’t he a friend? – he smacked one fist into the other and said ‘Ah, fuck! Why didn’t

they ask me?’ And when it came out he gave it what I felt was a very unkind review,

though perhaps I was over-reacting in feeling that.

As for the label ‘Generation of ’68’, I think Tom Shapcott first coined the phrase, back in

the early 1970s. I was happy to use the phrase because I had in mind the Indonesian

‘Generation of ’47’, those military men who graduated from the Dutch military academies

in 1947 and later fought to expel the Dutch from Indonesia. I had met some of them in

the early 1970s in Jakarta, General Abdul Haris Nasution for example, a thorough

gentleman. 1968 was of course the year of the ‘enevements’, the European and

Mexican and US student’s revolt’s ‘happenings’, so that fitted.

Fitch: Anyway, let’s get back to ‘The Anaglyph’, a poem of yours which may well see

itself in anthologies of the future.

Tranter: Thanks for the thought, but it’s a long and difficult poem, too long and too

difficult for the average anthology, I fear.

Fitch: I think it pushes your Starlight experiments with text-generating techniques

and with ‘translation’ (in this case from one English-language poem into another) to a

new limit, and creates a shape-shifting, organic form to mirror, or to talk through, the

movement of your career as a poet and the influences that have shaped it.

Tranter: That’s perceptive. Yes, those ideas were certainly in the back of my mind

when I was writing it, though the foremost plan was to do something with the Ashbery

poem ‘Clepsydra’, something clever and moving, that would live up to the original.

Fitch: In Corey Wakeling’s review of Starlight for Cordite, he describes ‘The Anaglyph’

as imperilling ‘the chameleonic bastard-experimentalist enough to name (you) as such.’

Do you also see this poem as a significant moment, or a rupture, in your work? Will it

see a shift to something uncompromisingly experimental in your next book?

Tranter: That’s a strange statement from Corey Wakeling. It’s a little difficult to work

out quite what he means, though it’s an energetic moment. Am I a chameleon? Am I a

bastard? Am I an experimentalist? I suppose so.

As usual, my next book will be a radical departure from all my others, or so I fondly

hope and imagine at the time, though in hindsight all my books are somewhat the same:

they’re all by me. Since we have lived in the age of free verse for over a century, perhaps

the only really radical and different thing to do is write rhymed verse. And yes, I do see

‘The Anaglyph’ as a significant poem, but then I would say that, wouldn’t I? But it is

not a rupture, no; more a development of trends that have been there all along.

It was the opening poem for my doctoral thesis, and in the Introduction to that I wrote

– excuse me for quoting myself – ‘This thesis is made up of a collection of 113 poems and

an exegesis. The poems are written in a mode that has become more prominent through

my writing career, in which the lineaments of another art-work, usually a poem or a

movie, are borrowed and transformed in some way, ranging from a simple imitative

exercise to homage to satire to critique to an experimental reworking of a genre

and its various examples. The exegesis examines this use of borrowing, mask or disguise

in the thesis poems, then steps back in time to explore this theme as it weaves its thread

through my twenty volumes of published poetry.’

If anyone is interested, they can download and read the entire thesis in PDF format

(for free!) from the website of the University of Wollongong:

http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3191/ But be warned: it took three years to write, and

it goes on for hours.

Fitch: Do you have a fixation with Ashbery? Is there something about obsession

that goes hand-in-hand with poets and/or writing poetry?

Tranter: No, not a fixation. He’s one of the best poets around, and when I discovered

his work, when I was a young poet, his influence was a very liberating one. I have

always been grateful for that. He is also very courteous and a good friend.

And he’s very smart. He has an extraordinary intellect and a vast cultural appetite.

When he was a teenager he was a nationally successful radio quiz kid – you have to be

really bright to do that – and he has degrees from Harvard and Columbia.

Once when we were having lunch in a New York restaurant he cocked his head on one

side and said ‘Hear that?’ I could hear some distant music, though I had no idea what

it was. ‘It’s the score from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg,’ he said, ‘the 1964 movie by

Jacques Demy. The music’s by Michel Legrand.’ I winced: I had seen the movie when

it came out forty years before, and had disliked it, and I had forgotten the music.

I mentioned that the three main literary models for my poetry have been Ashbery,

the mid-twentieth-century Australian hoax poet ‘Ern Malley’, and the nineteenth-

century French poet Arthur Rimbaud. They were each radical innovators, and as a

writer who grew up in Australia in the 1950s I felt that radical innovation was very

much needed here.

They were also each very smart. I’ve mentioned Ashbery; when Rimbaud was sixteen

he topped the Latin class in his school so overwhelmingly that the Imperial Prince wrote

him a congratulatory letter which his Latin teacher was delighted to read out to the

class. Harold Stewart and James McAuley, the joint creators of the hoax poet ‘Ern Malley’,

were both brilliant young men, full of promise. Not fully realised, alas, but who could

tell, then?

And here’s an odd fact: a Trivial Quiz question, perhaps. ‘What do these three poets

have in common? Arthur Rimbaud, John Ashbery and John Tranter.’ Answer:

‘They all grew up on remote farms.’ I believe we were in fact triplets, accidentally

separated at birth. And of course the spirit of Ern Malley, who died the year I was

born, passed into me through the process of metempsychosis, a favourite theme of

James Joyce, who just about built Ulysses on the idea of metempsychosis. In the

same way that both Bazza McKenzie and Dame Edna Everage are distorted embodiments

of Barry Humphries – ectoplasmic emanations, almost – I have always known that

I am a reincarnation of Ern Malley. It’s quite a responsibility.

As for obsessions, well, it seems that you need to be obsessional to continue with this

ill-rewarded career for a lifetime. It helps if you are clever, talented, well-read,

hard-working, obsessional and deeply stupid.

Fitch: Have you ever written and published poems under another name? Ever been

part of an attempted hoax?

Tranter: Oh yes, lots of other names. But hoax – well, almost, but not quite. I had seen

the damage the ‘Ern Malley’ affair caused. The internet database Austlit gives my several

pseudonyms: ‘Also writes as: Breshan, Joy H.; Dedalus; Hawthorn, Dorian; Heaslop,

Jennifer; Kruger, Chris; Kruse, Peter J.; Lynch, Patrick; Moore, Jo; Pallas, Mark; Simpson,

Rona; Smith, Tim; Thompson, Rupert’.

Those mostly come from the hoax magazine I wrote one morning in 1968, Free Grass.

You can read it here: http://johntranter.com/poems/free-grass.shtml. As a hoax, that

is generally good natured, I hope.

‘Joy H. Breshan’ is an anagram of ‘John Ashbery’ and comes from some computer

experiments I did a decade or so ago. ‘Rona Simpson’ was my disguise as Ron A. Simpson,

a Melbourne reviewer, when I wrote a piece on the late Michael Dransfield for Playboy

magazine. I don’t know why I did that. I guess I had written far too much on Dransfield,

and wanted to give the reader the illusion of reading someone fresh.

Fitch: And ‘Mark Pallas’? Where did that come from?

Tranter: Ah, ‘Mark Pallas’, another of my pseudonyms, is a more interesting case, named

after the Pallas’s Cat, Felis manul, a smaller version of the Snow Leopard, a unique feline

whose pupils are circular, and whose photograph I had liked in an encyclopaedia when I

was ten, partly because it looks as though someone has flattened his head with a blow from

a brick. Mark Pallas’s brief and slightly crazy poems appear in Transit magazine once or

twice.

Pallas’s cat, Felis manul, from the Encyclopaedia Britannica

11th edition, 1911.

Fitch: ‘Slightly crazy…’ Was he a projection of your own personality? He didn’t exist as

a person, is that right?

Tranter: I made him up. Yes, I feel he may well have been a projection of a slightly

strange aspect of my own personality, emerging through poetry. And even stranger,

I had the odd experience of talking with my friend and fellow poet Bruce Beaver once

in the late 1960s. He had met a young poet in a coffee lounge in Manly one night, Bruce

said, who chatted on at length about writing poetry. His name was Mark Pallas, he said,

and he had some poems in Transit magazine, published by that John Tranter fellow.

Very strange. I felt as though I had conjured him into existence, a ghost emerging out

of the darkness.

Fitch: Here’s a different kind of impersonation. The 56 poems of ‘Contre-Baudelaire’,

the last section of Starlight, present ‘radical revisions’ of Charles Baudelaire’s poems.

To me, there’s an extremely relaxed sense of fun and play in these poems. Is this

something that’s developed from years of writing? I’m reminded here, again, of a few

lines from your poem, ‘The Anaglyph’: ‘You hope your opus will be taken for

legerdemain, but your effort sinks / Deeper into the mulch of history, while I adjust

the mask that / Just fits more loosely every decade…’

Tranter: I’m glad you felt that sense of fun. I guess it partly comes from the technical

ease that I have developed over a lifetime of writing, yes. Partly. But I suspect it has

more to do with how I came to write those Baudelaire versions. In 2008 and 2009

I was thinking about how to finish a new book of poems. I had about a hundred poems

that were derived from the work I had done for my doctoral thesis, most of them

relentlessly experimental. I felt I needed about fifty more poems, and in a different and

more relaxed tone of voice. I had written a few poems about movies, which you

mentioned, and I shall probably write more, one day, but I wanted some more variety

for this book. Then I started thinking about Baudelaire, whose work I had liked a lot as

an adolescent, but which I had more or less ignored since. And I was having trouble

finding the time and the motivation to write much.

Then I received a surprise email from New York. A friend, the poet and editor David

Lehman, had put my name down for a scholarship to a writing retreat, without telling

me. The committee of the Ursula Corning Foundation chose me and a dozen other writers,

painters, and musicians from all around the world to attend a six week retreat in a

Renaissance castle in Umbria, in Italy, the Civitella Ranieri. You can look it up on the

internet. They sponsor four such gatherings every year. Did I wish to take up the offer?

You bet!

Fitch: Was that like a Writer-in-Residence thing?

Tranter: God, no. This was a real writers’ retreat. Your surroundings were

comfortable, and you had no obligations of any kind. If only the bureaucrats who run

things here could understand how vital that is.

With the last residency I did in Australia, I had little time of my own to write anything,

and lots of talks, readings, events and lectures to get through. I asked the organiser why

there were so many obligations, and he said that the bureaucrats wanted a good ROI –

Return on Investment – and that the Writer had to meet certain KPIs – Key Performance

Indicators. Spare us from such selfish generosity!

In late 2009 I flew to Italy – they reimbursed the air fare – and I had a huge studio and

a bedroom to myself high up in a tower in the castle, and two excellent meals were provided

every day. You fixed your own breakfast. The company was good: a dozen talented creative

artists, each cheerfully doing their thing. The dining room was always loud with laughter

and talk. The fall weather was perfect. There was literally nothing to do, if you didn’t want

to. So I wrote, all day, every day.

Fitch: You wrote all day every day for six weeks? I’d get distracted by the new

surroundings.

Tranter: I was too, for a while. And they had a few bus trips to visit local churches and

look at wonderful old paintings, which most of the other artists went on. I usually said no,

partly because I’m a bit shy, and partly because I had so much to get done, and like Arthur

Schlesinger Jr I felt I had seen enough wonderful art to last me.

When Schlesinger turned 60, he became more aware of his age. After a trip to the cathedral

in Florence, he wrote: ‘As I went into the Duomo, it occurred to me that I have been

visiting churches in Europe for 45 years, and that they have really done very little for me —

my fault, not theirs, of course; but there it is. Why should I waste my declining years going

into churches?… I will simplify life by abandoning the inspection of churches, as in earlier

years I have abandoned ballet, metaphysics, linguistics and other subjects that, however

estimable, are, alas, not for me.’ He lived to 89; a good innings.

And to be honest I didn’t write every day. I took a week to settle in and to do some Jacket

magazine editorial work that was urgent, and a week to wind up, when Lyn joined me and we

drove around Umbria. And I did go on one ‘outing’, with a busload of fellow-artists, on

dangerous winding dirt roads at night, to a remote restaurant in the mountains where they

fed you masses of truffles. Truffles in every course! It was their speciality. I can’t say I

learned to love truffles, but it was a wonderful outing. I loved the sense of camaraderie

and fun.

Fitch: So, in such seeming luxury, were partners allowed?

Tranter: No, only for the last week. And that seemed fair enough: it’s not really a

‘Roman Holiday’. You were there to write, and the less distractions the better. I think

most people write better when they’re on their own, and I like solitude. I grew up

somewhat isolated, and solitude was the norm.

So for four weeks I wrote and wrote and wrote, taking Baudelaire’s poems from his Les

Fleurs du mal (in French and in various English translations) and working them into more

or less contemporary poems only distantly related to their originals. I ended up with

fifty-six poems, about half of the total in Baudelaire’s book, which was just what I wanted.

Some of his poems were too depressing for me to want to spend much time with, cluttered

with tombstones and graves and rotting animal carcasses and people with awful diseases

and so forth, so I left many of those out.

The atmosphere I was working in was full of sunshine and play and limitless free time,

and the flavour of that ended up in the poems. I took lots of photos while I was there.

You can see them here:

http://johntranter.com/photos-by/index-umbria.html

Fitch: The poem ‘Goats and Monkeys’ begins: ‘Top executives and poets alike, when /

they grow old, keep pets…’ Do you have a pet?

Tranter: Yes, I had cats and dogs as a child. And Lyn and I have always had cats, from

the day we married in 1968. And once we became more settled – from say 1980 – we kept

dogs, including Cleo and Biscuit, both Basenjis. Biscuit is featured on the cover of the Salt

Companion to John Tranter.

And more lately a Manchester Terrier, then another Manchester Terrier.

There’s a poem – a rather sad poem – about a little dog in Starlight. It was loosely

based on a poem by Baudelaire about a cat, but I didn’t want to write about cats just then.

I grow very attached to pets, but they just don’t live long enough, that’s the awful thing.

They all die, one after the other, and I find that really hard to bear.

I should like to have a capybara, but I guess I’d have to live in Argentina for that to

happen.

Two capybaras anxiously discussing Wittgenstein’s apparent rejection

of some of the key propositions of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921).

Fitch: They’re larger than they look. Why the capybara? They’re preyed on by anacondas

and jaguars, right?

Tranter: And caiman crocodiles. You’re right, they look like nervous guinea pigs in

photos, but they are actually the size of large dogs when adult. They are giant rodents,

innocuous herbivores with no real defences, except to dive under the water. They spend

their time paddling around in shallow rivers, looking about anxiously and trembling.

They remind me of poets, I guess, only harmless.

Fitch: In a past interview, you said that you loved rock’n’roll as a teenager. You’ve

developed an international renown as a poet, and as founder and editor

of Jacket magazine, and you certainly know how to put on a show when reading /

talking in public. Do you think a sense of rock’n’roll has influenced your poetry

and your career and, if so, how?

Tranter: It’s nice that you feel I know how to put on a show when I give a reading.

I’m always aware that people have a choice as to how to spend their time.

Rock’n’roll? Yes. With my writing, I think I have been looking to create an art form that

could maybe give an audience a similar feeling of exaltation that good popular music

does. And rock’n’roll did shake things up: you only have to listen to the 1940s versions

of ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky’ – a mournful cowboy waltz in slow three-four time, with

acoustic guitar accompaniment, and then listen to what Elvis Presley

did to it in the fifties: very fast, very electric and very exuberant rock’n’roll in four-four

time. Look it up. The Internet makes that possible.

Of course with print publication, you can choose to present poems that are difficult

and complex or very long, and that may require two or three readings to give up most

of what they have to say. A reader curled up with a good book can browse back and

forth as they wish.

But with a live audience I try to choose poems that communicate most of what they

have to offer at one hearing, and it helps if they offer some auditory pleasure too, like

say rhyme or alliteration, or tell a story with a surprise ending in some way. Each poem

has a temporal duration, a duration the audience cannot guess at until the end happens,

and you can play with that. With a poem in a book, the reader can see right away if it is

a short or a long poem, and you can’t surprise them with a sudden abrupt ending.

I have performed a very long and difficult poem, but only once – actually the one we

were talking about, ‘The Anaglyph’ – at a conference in Melbourne in 2008; it ran for

over forty minutes. And it was read in Paris in 2011 by Antoine Cazé and Olivier

Brossard, and in Cambridge UK in 2012 by Jaya Savige, Michael Farrell and J.T. Welsch.

In my reading I tried to emphasise the humour in it, to help the audience get

through the thing. But as most of the audience were academics, perhaps I may have

been trying to make them suffer. You know, tenured academics have sabbaticals,

and long service leave, and holiday leave loading, and real holidays: all the things

that poets sadly lack. Not to mention a salary. Then again, the tenured academic is

virtually extinct these days.

There’s a poem by John Ashbery (him again!) that works beautifully read out aloud,

and I believe he read it for an audience in Ballarat in 1992, titled ‘We Were on the

Terrace Drinking Gin and Tonics’, and which reads:

When the squall came.

You can imagine the chuckle from the audience there.

Fitch: What about poets who explain their poems at length, prior to reading them?

Tranter: Yes, that can be awful. There’s a lovely parody of just such a writer by British

poet John Lucas, titled ‘The Next Poem’, which begins:

…which is called ‘Quick as Foxes’ and which can be found on page 479 of my Shorter Selected

for those of you who have the book will, I hope, in the words of T S Eliot, ‘communicate before

it is understood’, although as there are several allusions that may not be at once apparent but

which affect the overall meaning, I should like to note them, beginning with the title which some

of you will recognise from a minor poem by Wallace Stevens (who remains a major influence on

my work, and whose use of ‘quick’ to mean not merely ‘rapid’ but ‘alive’ and in a perhaps

Lawrentian manner ‘pregnant with foetus’) permits an implication that abuts on ‘thisness’

or haecceitas – a word my computer quite failed to recognize, and so repeatedly changed to

haircuts – the piquancy of which would of course have appealed to Stevens’s sense of the

fortuitous…

That kind of self-indulgent performance can be embarrassing, when it’s not hilarious.

But it does help the audience to grasp what’s going on if you give a brief – brief, not

verbose – introduction to each poem. Though some people say you shouldn’t explain

your work to an audience. Mallarmé wrote ‘Too precise a meaning / erases your

mysterious literature’. I usually ramble on for a few minutes between poems, about what

I thought I might have been trying to do. Maybe that just helps me and the audience

become less nervous.

And of course I try to read well, that is, to use my voice well. The Ancient Greek

and Roman poets studied rhetoric and voice training and the art of memory and

everything else that you need to present speech powerfully, whether you are

attacking a political rival in a law court, or pleasing your friends with a poetry

performance. Up to a hundred or so years ago they taught Rhetoric

in European and US universities. Not any more. We seem to have lost all that.

Fitch: You mentioned being nervous. Do you like attending or reading at poetry

events? As a shy person myself, I find that getting up in front of people — to talk, read

poems, give a paper or a speech, sing a song, whatever — is a kind of aversion therapy.

You said to me once in passing that you’re a shy person. How do you see this, this act

of getting up in front of people?

Tranter: I found it very hard, at first. I am shy, I was an only child, I had a lonely

childhood, blah blah. I used to stammer, and reading aloud for an audience was torture,

and I used to read too quickly. But as actors know, you disassociate when you act a part

– somehow you’re not yourself – and you can make a reading performance work for you

like an acting performance. And the more you do it, the easier it gets.

I eventually reached the stage where I enjoyed reading poems aloud, and that relaxes

the audience too. And a reading is more effective when the poet rehearses the

performance. I recall that when my wife Lyn and I put on a poetry reading at the PACT

theatre in Sydney in April 1969, I persuaded all the dozen or so poets to come to the

venue the day before and get the feel of the stage and the microphone, and do a

rehearsal. They all did, and they all read well on the night, except Bob Adamson. He

didn’t or couldn’t attend the rehearsal, and he fumbled the microphone

and didn’t read very persuasively. But we were all young then, and that was long ago.

It helps if the poet knows the poems thoroughly, and also knows how long the reading

of each poem will take. It’s irritating for the audience when a poet reads for a while then

anxiously asks the MC ‘Do I have any more time?’ It certainly breaks the spell.

And I try to learn my poems so I don’t need to keep looking at a script. It’s horrible to be

at a reading where the poets read quickly and inarticulately and keep their eyes fixed

on the page like frightened rabbits, and never look up at the audience. I used to do that.

Ugh!

Fitch: Of course not all good poets can read well on stage. I’m thinking also of some

songwriters whose fear of performing inhibits, even cripples, them, and who are often

better off as, simply, recording artists …

Tranter: Steeley Dan, for one. Though perhaps the complexity of their orchestrations,

and their use of great session musicians, makes the thought of live performance

unrealistic. And Dame Judy Dench confesses that even this late in her career (2012)

she has an awful recurring nightmare where she steps out onto the stage and her mind

goes totally blank: no lines, no words, nothing! That happens to me occasionally,

fortunately for a brief moment only. And I always have a script just in case.

I think performers owe it to their audience to learn how to do it well. Practice. I once

heard Geoffrey Hill read on stage on London. God, it was horrible. He was like a man with

a toothache or a migraine. He had a droning, complaining voice, and he started out by

saying how he hated reading out loud to an audience. Excuse me: we had all paid to be

his bloody audience, to hear him read, and we had all given up some of our precious

leisure time to do so. We can learn a lot from performers like jazz singer Anita O’Day.

Have you ever seen the 1959 movie Jazz on a Summer’s Day? It’s exhilarating. Rent

a DVD. When she sings her songs – that is, reads rhyming poems set to music – she never

looks down at a script, and she engages her audience all the time, clearly loving what

she does. You can see the smile – those big teeth! –and you can hear the smile in her

voice. She makes sure she looks good – new hat, gorgeous frock – and you can bet

that she rehearses and rehearses and rehearses. Of course there’s money in it, for

singers, and that concentrates the mind; not so for poets.

Fitch: Rimbaud liked erotic books full of misspellings and little children’s books,

if we’re to read his poem ‘Alchemy of the Word’ from A Season in Hell biographically.

Do you have any unexpected reading habits?

Tranter: I think there’s something slightly creepy about ‘erotica’. There seems to be

a flood of ‘erotica’, or semi-porn, e-books lately. Erotic books… but who can bother

to read, these days? Millions of porn videos are available on YouTube and other

Internet sites.

Fitch: Maybe it’s the way a reader has to use their imagination to picture something…

Maybe that’s what still piques a good reading session?

Tranter: Yes, the audience needs to have their imaginations exercised by the poems

they’re hearing. I suspect that’s why good comedians are successful: the images and

events they create in the imagination of the audience are vivid and bizarre. The

misspellings that Rimbaud liked are somehow appropriate, though: lexically incorrect

and politically incorrect all at once.

I am a compulsive reader, like all my mother’s side of the family, and like most people

of Scots descent. The Scots invented the Encyclopaedia Britannica, in Edinburgh,

I suspect so people would have something useful to read through the long Scottish

winters. I’ll read anything, really; a road atlas if that’s all that is available. I discovered

I share that with the German poet H M Enzensberger: we both like atlases.

I seek out and enjoy photography magazines and articles about computers and

typesetting. I used to buy two or three magazines every month. Now I spend hours on

the Internet each day, looking at things like that. And articles about fountain pens, and

stationery and bookbinding. My Internet journal has a list of links to sites I like, at

johntranter.net. Take a look at the foot of the right-hand side of the front page.

Fitch: You mentioned compiling the last two volumes/years of Black Inc.’s Best Of

Australian Poems anthology. You must have read a great deal of contemporary

Australian poetry. What would you say are the trends, if any, at the moment? What

turns you on and what doesn’t?

Tranter: Oh God yes, I have read over two thousand poems in the last two years, for

those anthologies. I don’t really look for trends, or care much for them. Trends tend to

be selective in any case. Some writers follow this trend, some writers follow that other

trend, whereas a good poem doesn’t necessarily follow any trend. Perhaps it creates

one, like Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’; but you don’t know that at the time.

And editing those anthologies is not like editing my first poetry anthology, the very

polemical The New Australian Poetry (1979), that we’ve mentioned already. With these

‘Best Of’ collections, you are asked to select the best – whatever that is – from among what

you’re given, over a thousand poems which people send in from that year’s publications.

You can’t add anything, and the variety is vast. That’s the good thing: each year you

come across a thousand different poems, as different as fingerprints, from people you

have often never heard of. And you publish what you feel are the best. And thousands

of people read them. That’s wonderful!

Fitch: But what do you look for?

Tranter: I seem to do things by instinct, so I’m not aware of what I’m looking for until

I find it. What pleases me is technical skill, humour, cleverness, sincerity, passion, pathos,

the whole thing. Different poets offer different things. A good poem usually jumps out

at you, if you’re receptive. And if you have a ‘program’ you’ll miss out on some

wonderful pieces of writing, so I try to let myself be guided by the poems themselves.

I don’t care about names or reputations when I’m compiling these anthologies: that

wouldn’t be fair on the reader, would it? In fact I often cover over the names of the poets

as I read, so as to surprise myself. I like the fact that so many of the good poems are by

writers I don’t know.

For example, to me one of the loveliest poems in this year’s anthology (Best Australian

Poems 2012) is ‘My Town’ by Meg Mooney, a writer I had never heard of. It’s outwardly

a casual poem, about a person walking down the main street of a country town, saying

hi to some friends, maybe having a difficult day. That’s all. But the last line contains a

brief and touching confession of loss and grief, all the more effective for being so lightly

drawn, and being placed right at the very end. I would give my right arm to have

written that. Casual, moving, beautiful.

Fitch: Who are some Australian poets whose work you read and reread? Why do you

return to these poets and whose books are you looking forward to reading in the coming

months?

Tranter: If I name a few names I’ll offend all those I don’t name, so I won’t. Of course

I like and read writers from my own generation, but also some older poets and lots of

younger poets. Well, there are many more younger poets. Most Australians are

younger than thirty-eight. And I am glad there are so many good younger poets, all

with fresh ideas and new things to say, so I like reading them.

And overseas there’s a new anthology of young British poets just out from Salt

Publishing, The Salt Book of Younger Poets, that I’m looking forward to reading, and

Paul Hoover’s 1994 anthology Postmodern American Poetry has a larger second

edition just out.

Over my lifetime I have read far too many poems by other people, most of them

not first-rate, inevitably. For example, when I read through the six thousand entries

for the Tin Wash Dish anthology in 1988, over five thousand of them were not all that

good, as it happens. Which is fine, in the end; that doesn’t bother me. But for pleasure

I sometimes like something quite different. A good road atlas, say.

Fitch: Who are some non-western poets or, should I say, non-European and non-

American poets that interest you, past or present? Can you say a little about why and

how these poets appeal to you, as opposed to, say, your French and American

influences?

Tranter: When I was young I read a lot of Chinese poetry in translation. Li Bai (Li Po)

and Tu Fu are wonderful, but everyone says that. I was greatly impressed by Robert

Payne’s anthology of Chinese poetry over the last two thousand years, The White

Pony (Mentor, New York, 1960). Other Chinese poets whose work I like include Wang

Wei, Po Chu-i, and Su T’ung-po. There’s a lovely clarity and colour to their work, and

a strange linking of philosophy and nature, and they’re free of the romantic

individuality and boastfulness of many western writers. But I am naturally more

inclined to read among European and American writers, because of the cultural issues

I find I can relate to there.

Fitch: Any contemporary Asian poets?

Tranter: I’m looking forward to discovering some in Singapore, where I shall be soon,

for the Singapore Writers Festival, November 2012. There seem to be thousands of them

attending. And Ouyang Yu has translated some very interesting modern Chinese poets

which appear in the Best Australian Poems 2012 anthology I’ve just edited: De Er He,

Shu Ting and Shu Cai.

But I am forgetting a Singapore-born prose writer whose work I loved as a boy and