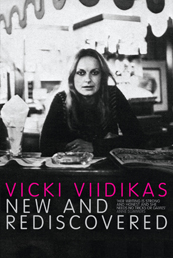

Martin Edmond Reviews Vicki Viidikas’ “New and Rediscovered”

New and Rediscovered

New and Rediscovered

by Vicki Viidikas

May 2010

ISBN: 9780980571769

REVIEWED BY MARTIN EDMOND

That Incorrigible Weapon: Vicki Viidikas, New and Rediscovered

A few years ago a friend who lives in Queensland asked me if I would mind having a look around the second hand bookshops in Sydney for the only one of Vicki Viidikas’ four books he didn’t own a copy of: Knabel, her third, published by Wild & Woolley in 1978. One very hot January day I stopped in at Gould’s in King Street, Newtown and spent an irritable half hour or so looking through the poetry section for a book I felt sure was there but could not find; I remember the black dust from the street that coats all the books on the lower shelves sticking to my sweating hands like a contagion. Some weeks later, on a whim, I called in again and this time found a copy in a matter of minutes.

When I took it to the desk to pay Bob Gould, sitting up on his high seat, began to reminisce. Such a fine writer, he said. So sad. Do you know, she came in here just a few weeks before she died, to sell some books? She was getting rid of her library in stages in order to finance her drug addiction … as he spoke, incongruously, he began taking rolls of banknotes from his pockets, presumably the day’s takings, and handing them up to a young acolyte standing at his shoulder. It seemed an apt illustration of the relationship between writers, books and money.

At this point I had not read any of Viidikas’ work and didn’t really look at Knabel either; just parcelled it up and sent it off to Rockhampton. I was however aware of a flavour, indeed an aura, around her memory—several older writers I knew, my Queensland friend among them, sometimes spoke of her, always with an oddly wistful tone in their voice. It wasn’t like they were recalling a companion or lover of their youth; rather it was if something unique and irreplaceable had gone out of the world when Viidikas died, aged fifty, in 1998. Now, a dozen or so years later, we have a selection of her work edited by Barry Scott and published in a handsome edition by Transit Lounge. And so it is possible to approach the question of what kind of writer she was.

The selection is substantial and includes material from all her books as well as about twenty previously uncollected pieces. It consists of poetry and prose and is ordered roughly chronologically (some pieces are clearly out of sequence), without making any particular distinction between her two main modes of writing: that is, free form poems and prose pieces which are usually short, even compressed, and at times resemble prose poems. There are also eight colour plates of naïve drawings and excerpts from two longer works: an unpublished novel called Kali and the Dung Beetle and a sequence entitled Prisoner Poems. The selection works well and the book can be read, as I read it, straight through from start to finish as if it were a kind of autobiography.

A peculiar sort of autobiography, however. Viidikas is not primarily interested in herself as much as in things seen and done; she is neither analytical or theoretical and nor is she disposed towards the drawing of conclusions—or, god forbid, morals. She instead sends despatches from the frontiers of experience, with the emphasis always upon the nature of the experience rather than the nature of the self who experiences. That is to say, she is an instinctive writer who is driven to write down things that happened to her, or that she made happen, as they happened. Many of the short prose pieces, for instance, are really character sketches of people she has known and some among them are unforgettable: individuals you will not meet anywhere else in Australian writing though you might still come across them in the street.

The poems, which seem rather more extempore, like the prose usually bear a strong trace of their occasion and those occasions are frequently, though not always, traumatic. The focus upon experience rather than self makes of these apparently confessional pieces something more like reportage; yet it is reportage that does not deny the full participation of the self: an analogy might perhaps be found in the work of Herbert Huncke, who also put himself in the way of extreme situations and then wrote up the results. Like Huncke, Viidikas casts a cold eye on life, on death and the complications that ensue in the passage from one to the other; and if the lack of self pity, even of self regard, is both bracing and disconcerting, it has also the paradoxical effect of making us feel we know what it was like to be her without a concomitant sense of knowing what it would have been like to know her.

This entails, I think, another paradox: the self that negotiates these experiences, this brave, reckless, honest, insouciant, hyper-aware voyager, discloses herself primarily as wound or, less surely, scar. Self as wound is not the intent of the writer but a consequence of her writing; and because she is not analytical, the effect is of a vulnerability that is pure, intense and unannealed. Therefore it is not a surprise to find her, in the latter stages of the book, describing the country of addiction from the point of view of an insider, a long-term resident, and ultimately someone who will find it impossible to leave. There are many kinds of addict and many reasons why people become addicted; one, certainly, is that heroin is a great salve of mental pain.

Viidikas seems gradually have fallen silent; her last book, India Ink, came out in 1984, fourteen years before her death, and she did not publish much in magazines in those later years either. However, it would be a mistake to let that encroaching silence shadow the earlier work: she is one of those rare writers whose every utterance is worthy of attention; or, to put it another way, she did not write unless she had something to say. Her major themes—they way or ways in which men and women relate, especially sexually; the nature of religious or other kinds of rhapsodic experience; the exotic as it appears to the committed traveller—do not date and hence her dispatches from the frontiers she explored or transgressed remain vivid and contemporary.

Her longish story of an affair with a young Cretan man, for instance, told with unflinching honesty, could stand as a paradigm of all such encounters and includes, at its climax, a haunting insight into the effect the violence of men has upon the affections of women. Similarly, her hair-raising account of a night out in the environs of Bangkok, trying to buy marijuana, is a narrative which could easily have ended in a murder—her own—and thus gives insight into encounters that may not have finished so well. Her Indian experiences, which were extensive, have a dynamic that oscillates between revelation and disenchantment and I wondered if the unpublished Kali and the Dung Beetle, which must on the evidence of the extract given here shed more light on this aspect of her consciousness, will ever come out in full.

Of course certain kinds of religious experience do also bring the pilgrim to a place of silence, a nirvana that might bear some superficial resemblance to the muted trance of the addict; in both states the fealty to experience that leaves such a strong trace through Viidikas’ writing is replaced by something that may not require a witness or indeed witnessing. Even as skilled and committed writer as Viidikas might long for a cessation of the effort of composition as well as an end to the necessity of wrenching from the world material that may then be composed. The last poem in the book, Lust, written just two months before her death, is a kind of renunciation of the sexual adventuring anatomised in the rest of the book; when she writes Who will bring back the beauty / the ecstasy, the mystery / of creation? you know that she (the last spinster) no longer considers that a task she can fulfil.

I did wonder what the books were that Vicki Viidikas sold to Gould’s around the time of the composition of Lust; but, having told me the bare bones of the anecdote, the bookseller would not say any more. He took my dollars, handed them up to the young fellow at his elbow and turned his mind to other things. Kerry Lewes, in the introduction to this selection, does list some favourite writers, mostly European: Akhmatova, Djuna Barnes, Baudelaire, Beckett, Cavafy, Cendrars, Éluard, Grass, Herbert, Holub, Popa, Prévert . . . but not Rilke and not Rimbaud either. Nevertheless Viidikas’ densely compacted, highly allusive, linguistically inventive prose poems do sometimes recall Illuminations; as her courage, her despair and her silence echo the doomed Rimbaldian trajectory.

Letter to an Unknown Prisoner, a late piece (1990), begins: Today was almost impossible to begin, with no sleep, all night tossing like bunkers on a great ship, far out on the Arabian Ocean . . . ; and ends: Freedom, to unlock denial; freedom, that incorrigible weapon. A weapon that she seems to have used, both in writing and in life, in every possible manner she could devise; and then with great generosity reported openly, skilfully, truthfully and beautifully upon the results.

.jpg)