“The End of the World” by Maria Takolander reviewed by Jacinta Le Plastrier

The End of the World

The End of the World

Maria Takolander

Giramondo

ISBN 9781922146519

Reviewed by JACINTA LE PLASTRIER

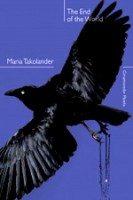

In native American and other cultural traditions, the raven has a powerful symbology. It is considered a messenger who carries information between worlds, is of the earth but also capable of bridging to other realms. It can also represent the souls of the murdered. In this, it is an apt choice as the cover illustration of Maria Takolander’s second full poetry collection, The End of the World.

There is no direct reference to a raven in any of the book’s 41 poems but certainly it could be argued, as a lens for its reading, that many of them either directly or implicitly address the presence of the otherworldly, the ethereal and the spectral. There are also veils between the earthly world and our perception of it, and between a self’s experience and its familial and historic connections and heritages.

As Takolander writes in the first poem of the book, ‘Unborn’, which addresses pregnancy, ‘Still emerging from yourself, the bud of your nose alone/ makes the universe less impossible. You do not know/ that we are here, but this is how we watch you: on a/ black-and-white plasma screen suspended on a wall/ – the happy technician flicking us between dimensions/ like Dr Who – and as if from an infinite distance.’

This is a second collection and while the poet carries through themes begun in her first book, Ghostly Subjects (SALT, 2009), particularly in regard to poems about the intimate self and her family’s history in the first two parts of The End of the World, it also sets out on what feels like a new orientation – especially in the book’s final third section. These poems spring beyond the field of own experience.

In his recent non-fiction book, A History of Silence: A Family Memoir (Text Publishing, 2013), NZ author Lloyd Jones contends, ‘a writer’s works have a way of tracking back to his wellsprings.’ In the context of his book, this meant an examination of his lineage’s ‘ancestry of silence’, and ‘the sediment within him’. These are useful ideas to apply to the work in The End of the World where Takolander exhumes her own family’s spectres.

These ghosts are not only familial. They are also metaphysical, those of the dark imagination which has inhabited this poet’s work from her earliest poems, published in the 2005 chapbook, Narcissism (Whitmore Poetry Press).

Of Finnish origin, Takolander’s family members were killed in Stalinist purges. Some were exiled or they experienced other horrors of war. The traumatic consequences of these experiences, for themselves and descendants, are insidious and potent. It is a brave poetry which addresses them.

In one of the finest poems in Ghostly Subjects, ‘Finland: Fables’, Takolander assized this family history in prose-poetry wording, each stanza a long-lined sentence:

In a kitchen there was a man who drank the worlds contained in bottles, but who could never find the strangers he had killed in the

war, whose blood had melted with the snow.

It is subject matter reprised yet differently confronted in a number of poems in Part 2 of the The End of the World, including ‘Mushrooms’ and ‘The Old World’. These are moving poems. In them Takolander explores not only for herself, as poet and a self, but also in poems such as ‘The Old World’ gives voice to the those gone before us, whose aching for what has been lost might (perhaps inevitably will) re-sprout in those who follow. The poem closes, ‘See how the sun burns all night, like a promise/ of the end of the world.’ This is one reference to the book’s title.

Later in Part 2 is the poem actually titled ‘The End of the World’. The subject matter is the history of and a visit to Punta Arena, Chile. Written in five-lined stanzas, it closes in language of an edged, gothic beauty:

…

their skullbones and cross-bones now encrypted

in the cemetery across the way, where angels dive among

cypresses manicured into a wonderland silence

that takes the edge off death and the sight

of all those abominable dogs, ranging everywhere.

This poem is an example of what has marked Takolander’s poetry since its beginnings. There is a discipline of form though she is writing in free verse which allows it to have the echo of formal metrics within it. This tendency is always an opportunity for a poet to clarify and amplify their poetic thinking – the movement of mind in the work. There has also prevailed in her poetry – though it might be a strange term to use – a discipline in the language she chooses as her oeuvre’s ‘field’. It is an educated vocabulary but with a sense of the pared, of having been boned – also of the elemental or even glacial. I think of an earlier poem like ‘Storm’:

…

It may be true we don’t deserve this,

Our earthly things reduced

To shadows we dream

Things from: the firs, the stooks,

The fence posts¾none belong.

They don’t belong.

Yet we’ve always waked and slept

When the sky says we should,

Like birds and monkeys,

Abandoning the world

Evening after evening…

The majority of poems in The End of the World combine this clarified language with a formal control – and their poetic ideas are robust – but there are a number which don’t, and which make for uneasy reading. In these, certain lines or phrases are weak but the main concern is that the poetic conception has not been deepened – pressurized – sufficiently in the process of their creation. One example is in a poem about her forebears, ‘Missing in Action’. The material is unusual and powerful – her great-grandfather, ‘lost to Stalinist purges’, an eldest uncle, ‘dysentery got him as an infant in Karelia’, a grandfather of which she writes ‘(Hung over, he would beat the horses, their flanks shivering.’). And the formal structure is clear. There are lines in the poem which spark, but a major part of the poem’s language and its thinking through is not brought up to the task of interrogating – and so unearthing meaning – of such a tragic territory. (This is most definitely not the case with the earlier ‘Finland: Fables’, which traversed similar subjects.)

It is uncomfortable to criticize a poem whose material is profound, and of obvious importance to the poet. Having said that, in stark contrast is perhaps the finest poem in the new book, ‘Stalin Confesses’. Adopting Stalin as subject, the narrating, poetic voice is both authoritative and, in the most positive sense, destabilized and destabilizing. One wonders, at different points through the poem, ‘who is speaking now?’ This shifting of angles is beautifully controlled. The poem begins: ‘At my side I have concealed a child/ whose body was twice trodden by horses/ hauling carriages through our boggy village,/ the hooves like machines./ The child’s father, sludge-drunk and stone-fisted, beat him,/ as did his mother, full of God./ The seminary silenced his Georgian tongue,/ and the Russian army, even in war’s thick, rejected him./ The child’s face is smudged as the moon’s.’ Here is poetry whose language is muscled, precise yet allusive. It startles, and its promise drives through the whole work. Later is this: ‘He once entrusted to me a chronic dream/ in which his mother, father, unborn brothers,/ soiled villagers in their carts,/ the priest in his finery, and even God Himself/ will not, no matter the torment he inflicts on them,/ look upon his scorched soul/ and confess they were responsible.’

In Part 3 of The End of the World, Takolander takes up a different poetic drum. This poetry is sometimes fantastical – the final four prose poems are inhabited by Aesopic animals and the twists of fable. The part opens with poems, one section in catalogue form, inspired after 19th-century ‘scientific’ treatises on criminology.

Here, in a later poem, are the opening lines of ‘Witch’:

Her Hair was the Colour of Dirt, her Fingernails

of Stone, but she did not Lack Shelter or Know Hunger.

She Knew how the Body forces the Foetus to leave

its Mucous Womb and Breathe Air, and she could effect

Certain Remedies for Those Unwanted, rendering

The Creatures, While Still Hidden, Powerless. Small

Corpses were not Such a Problem. …

This final part to the book is adventurous and its subject matter and wielding, strange and beguiling.

JACINTA LE PLASTRIER is a Melbourne-based poet, writer, editor and publisher. Her poetry collection is forthcoming with John Leonard Press. To read more, Jacinta Le Plastrier