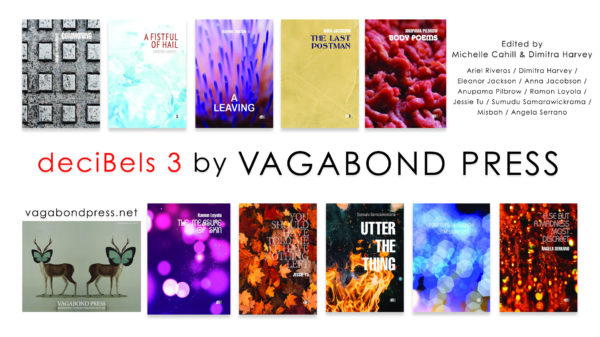

Navigable Ink

Navigable Ink

by Jennifer McKenzie

ISBN:P 978-1-925760-52-1

Transit Lounge

Reviewed by ANNEE LAWRENCE

Jennifer Mackenzie’s collection of poems Navigable Ink takes inspiration from, reveres and amplifies the life events, writings, reflections and concerns with history of the Indonesian author and activist, Pramoedya Ananta Toer (1925-2006). The idea of writing the poems emerged after Mackenzie was asked to translate Pramoedya’s Arus Balik (Cross-Currents) in 1993.

Pramoedya Ananta Toer was born in the small Javanese town of Blora in what was then the Netherlands East Indies. His most famous work, the Buru Quartet novels – This Earth of Mankind, Child of All Nations, Footsteps and House of Glass – covers, in his own words, Indonesia’s time of Nationalist Awakening during the first two decades of the twentieth century.

Based on the life of the pioneer journalist Tirto Adi Suryo 1, the novels follow a young man, Minke’s, developing political awareness and consciousness of the colonial apartheid system. As his story unfolds, the reader is drawn into an emerging vision of a new country – Indonesia, and of a new national language and cultural identity – Indonesian. 2

When Suharto’s New Order government came to power after a military coup in 1965, it did so by overthrowing the government of the nation’s first President, Sukarno (in power since 1945) 3. The coup unleashed widespread violence and the extrajudicial bloody deaths of more than half a million people who were labelled communist or communist sympathiser. Feminists, trade union leaders, teachers, artists, writers, doctors, farmers, university lecturers, and all kinds of progressive community leaders lost their lives. Of those who survived, many were shipped without trial or sentence to the island of Buru where they were forced to do hard labour.

Pramoedya was imprisoned three times during his life: in 1947-1949 by the Dutch, for nine months in the 1950s by the Sukarno government, and in 1965-1979 by Suharto’s New Order regime. At the time of his arrest and imprisonment in Jakarta on 13 October 1965, his house was ransacked and his library and eight of his manuscripts were burned.

Mackenzie’s poem, ‘Manuscripts in My Library Destroyed by the Mob’ lists Pramoedya’s works and writing that were stolen or burned in 1965 – works about and by Kartini and other women writers before Kartini, a collection of Sukarno’s short stories, a preliminary Study of the History of the Indonesian Language – the list is telling. They represent the voices that must be silenced, histories that must be erased or reinterpreted including that of the birth of the country’s national language. When Pramoedya sought to recover ‘two volumes of Pre-Indonesian Literature’ he was told by the director of the Balai Pustaka (the Government Publishing and Printing House) that they were ‘burned at the request of his superiors’.

After four years in prison, Pramoedya was taken 1500 kilometres east by ship to the island of Buru on 16 August 1969, where he remained as a political prisoner until 12 November 1979. Buru was a barren, infertile swamp and life for the political prisoners was characterised by daily beatings, hard labour, hunger and filthy conditions. In the poem ‘Writing Materials’, Mackenzie captures the insane mechanics of the arbitrary and senseless repression on Buru that denied the author pen and paper.

there was no pen, no paper

then there was

after many years

pen and paper

I wrote

in delirium

I remember none of

it

At the poem’s conclusion Mackenzie does not look away from the trauma that has done its work: ‘nightmares lap the house/which wall is crumbling?’

The eventual provision of writing materials allowed Pramoedya to finally begin to write the four novels of the Buru quartet that had been kept alive in his memory by narrating them to his fellow political prisoners.

On returning home to East Jakarta on 21 December 1979, Pramoedya was placed under house arrest and made to report weekly to the local police station. For almost two decades, he and his family endured constant and systemic discrimination and surveillance. As each of his books was published during the 1980s and 1990s, they were banned – allegedly for spreading Marxism-Leninism and Communism.

During Suharto’s thirty-three-year New Order regime, the gap between rich and poor widened, and corruption, cronyism and fraud became widespread. When the economic crisis took hold in the latter part of 1997, the country’s students faced down the authorities and took to the streets, and the seemingly entrenched President was finally forced to stand down on 21 May 1998.

In Navigable Ink’s opening poem, ‘Before Nightfall’, there is at first moonlight and tranquillity, but attention soon shifts to the sea – gara gara – turbulence, trouble, stormy weather, and ‘frenzied moonlit waves’ that threaten those on board. On the shore there is the howling of forest dogs. From the darkness, having disappeared from view of family and society for more than fourteen years, the political exile returns white-headed to his family, finds his daughters once more at his side, ‘forest and grassland will always greet/each other’, while they giggle and tease ‘You look like Hanuman’, the white monkey general of the Ramayana.

Images of the sea, the coast, boats, boat journeys, and foreign armadas appearing to bomb the islands’ ports with cannon ball – ‘they want to plant their flags on this very shore!’ – are threaded throughout different poems. They mark devastating invasion and journeys into exile. Life goes on and there is a unity of design, the link to precolonial and colonial events, the death or enforced exile of those who use words to agitate and need to be shut up, and the relentless environmental destruction caused by cutting down forests to make way for cash crops (most recently palm oil plantations).

In ‘Daendels as Wayang Puppet Watching Over Us’ Mackenzie draws on Pramoedya’s film essay, Jalan Raya Pos (the Great Post Road) 4, with translations of Pramoedya’s text captured on the right side of the poem, alongside the scenes filmed on the road of workers ‘sodden, flooded, collecting sand/this rushing river’, ‘stoking the furnace of the sugar mill’, trying to repair ‘a mudslide’, and of ‘a wayang performance/the puppets of Daendels, the Regent of Sumedang/a cracking gamelan/battle it out’.

The one-thousand-kilometre Great Post Road extends across northern Java, from Anyer on the West coast to the port of Panurukan in the East. It is the ghosted legacy of the Dutch Governor-General Daendels who in just one year in 1809 conscripted Javanese labourers to build it. Many died in the process.

In the film essay, the road remains the lifeblood of transport and communication for cars, carts, public buses, and trucks, but its history echoes the Suharto era’s own use of the unpaid labour of the political prisoners to build roads and bridges on Buru, and the inequality, poverty and poor working conditions of those at work along the road.

One of the scenes of ordinary daily life and survival captured is the attempt of a driver to repair his broken down truck in pouring rain. Mackenzie captures this in ‘Writer’s Block’.

WRITER’S BLOCK

rain soaking

a break down

diesel fumes rising like clouds

a rinse in the river of spare parts

the bus will rattle into life

eventually

WRITER’S BLOCK

The poem draws on other scenes from the film essay including one in which Pramoedya admits that when he is affected by writer’s block, the study of his homeland and its history are a key tool for organising his thoughts.

The film also bears witness to Pramoedya’s daily routine. The passing of time. The push-ups, the burning of rubbish, the ‘click click click’ of the typewriter. The joy of grandchildren. Trauma kept at bay.

Mackenzie’s poems reflect the contemporary as well as the past. Young people leave their rural towns and villages to seek better lives on the coast where they find themselves living on the margins of broken dreams – as drivers, tea pickers, sand miners, or carting bamboo as in ‘The Buffaloes’:

the buffaloes, in a choreography of the tethered,

lift their feet lightly

above the wagon

drooping bamboo branches

sway, leaves catching the light

at the swirling’s centre the driver’s steady gaze

In the three-part poem ‘Memories of the Revolution’, ‘Bandung Conference 1955’ recalls the coming together of emerging nations called on by Sukarno (as NEFOS – new emerging forces) to refuse allegiance to one or other side of the Cold War. In the second part, ‘Borobodur 1959’ depicts a visit to Indonesia by Che Guevara. In part three, ‘Jakarta 1995’, the Cold War has ended, the prisoners from Buru have returned to their families where they are demeaned and discriminated against as ex political prisoners (TAPOL). This ongoing persecution (denial of jobs and education) under the New Order government extends to their children and other close family members.

In ‘Jakarta 1995’ the snapshot of scenes from daily life at home skews to the right across the page, fulfilling a pattern of days in the present, ‘watering the plants’, ‘gazing over to the/neighbourhood kids/springing about/flying kites’, but still reckoning with the past, still ‘thinking of Sukarno’, and arriving at a single word, ‘sunyata’ – in truth.

For Pramoedya, remembering is agency, truth telling, and revolutionary act. And personal survival, relationship and day-to-day living are necessarily intertwined with the political.

The poems in Mackenzie’s collection are a brilliantly realised weaving of Pramoedya’s preoccupation with the images and episodes of history which flow like ghosts into the present. If the nation could be ‘unified politically and administratively by Soekarno without spilling blood – an exceptional occurrence in humanity’s history’,5 – then how are we to understand the widespread horrific violence against their own that exploded in the wake of the US military-backed coup in 1965?

Pramoedya interrogates history and demands that the present be understood, and if it can be understood, he asks, then what is the role of the literary writer? In his essay, ‘My Apologies, in the Name of Experience’ he writes that ‘as a person and a writer who shares in bearing the burden of change’, he regards the era of Sukarno (until 1965) and the Trisakti doctrine as ‘nothing but a sort of thesis. The New Order, an antithesis. Therefore, for me, it is something that in fact cannot be written about yet, a process that cannot yet be written as literature, that does not yet constitute a national process in its totality, because it is in fact still heading for its synthesis.’6

In the last poem in the collection ‘Dawn’, the train heads east from Gambir station, crossing through the countryside,

red mounds of earth high as small hills

on either side of the narrow track farewell

what I sense of

myself

And, at the end, a self that wears the marks and traces of brutal capture and incarceration, but who also goes on amid the details of daily living.

a chattering of bicycles and tea stalls

among the mud and puddles left after rain

my skin,

hoed, black beaten, weathered, flaking away

my life

Mackenzie’s Navigable Ink honours the inspiring, rich literary legacy of Indonesia’s most notable writer and pays tribute to his refusal to be silenced, subjugated or compromised. It is a wonderful collection that repays multiple readings.

Notes

1. Max Lane translated the Buru Quartet and as he writes in his Introduction to Footsteps (1990): ‘Tirto Adi Suryo was publisher and editor of the first native-owned daily paper, instigator of the first “legal aid service”, co-founder of the first modern political organization, co-publisher of the first magazine for women, and a pioneer of indigenous literature in the language of the nation yet to be born. All this and more is brought to life for the reader in an amazing adventure of intellectual discovery and emotion.’

(p. 10)

2. Max Lane, Introduction, in Footsteps by Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Penguin, 1990, p. 10.

3. In 1942 the Netherlands East Indies surrendered to the Japanese and, after the war ended, the

Indonesian nationalist leaders, Sukarno and Hatta, declared Indonesia’s independence on 17 August 1945. Sukarno was the nation’s first president and Hatta its vice-president. After four years of struggle, the Netherlands recognised Indonesian independence in 1949.

4. Jalan Raya Pos 1996, with Pramoedya Ananta Toer. Directed by Bernie IJdis.

5. Chris GoGwilt, 1996. ‘Pramoedya's Fiction and History: An Interview With Indonesian Novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer, January 16, 1995, Jakarta, Indonesia’, The Yale Journal of Criticism 9.1: 147-164. http://muse.jhu.edu.ezproxy.uws.edu.au/journals/yale_journal_of_criticism/v009/9.1toer01.html

6. See Pramoedya Ananta Toer, 1991. ‘My Apologies in the Name of Experience’. Translation and

Afterword by Alex G Bardsley, 1996. https://sites.google.com/site/pramoedyasite/home/works-in-

translation/my-apologies-in-the-name-of-experience In the essay, Pramoedya relates that ‘the period of Guided Democracy in the last years of the 50s and first half of the 60s, [was] the period of the Trisakti doctrine – political sovereignty, economic self-reliance, cultural integrity – a doctrine that, while universal among nationalist states everywhere, was, however, a bogey for the countries stuffed with capital, and hungry for new fields of enterprise around the world. History teaches much about the power of capital. … The governments of so many states it turns into mere instruments of its will; and when they are no longer wanted, they are overthrown.'

ANNEE LAWRENCE’S debut novel, The Colour of Things Unseen (Aurora Metro, UK, 2020), engages with the rich cultural life that exists between Indonesians and Australians. She was the inaugural recipient of the Asialink Arts Tulis Australia-Indonesia Writing Exchange in 2018 (at Komunitas Salihara in Jakarta) and has published in New Writing, Griffith Review, Hecate, Cultural Studies Review and the online University of Edinburgh Dangerous Women Project.

Gunk Baby

Gunk Baby Monsters

Monsters Against Certain Capture

Against Certain Capture I Said The Sea Was Folded

I Said The Sea Was Folded Song of the Crocodile

Song of the Crocodile  The Other Half of You

The Other Half of You Second City: Essays From Western Sydney

Second City: Essays From Western Sydney No Document

No Document Know Your Country

Know Your Country Where the Fruit Falls

Where the Fruit Falls Dropbear

Dropbear

Motherhood

Motherhood Navigable Ink

Navigable Ink Echoes

Echoes Peace Crimes: Pine Gap, National Security and Dissent

Peace Crimes: Pine Gap, National Security and Dissent The House of Youssef

The House of Youssef  A History of What I’ll Become

A History of What I’ll Become  Change Machine

Change Machine A Kinder Sea

A Kinder Sea Throat

Throat The Wandering

The Wandering  Case Notes

Case Notes Kokomo

Kokomo Stone Sky Gold Mountain

Stone Sky Gold Mountain Entries

Entries The Tiniest House of Time

The Tiniest House of Time A Passing Bell: Ghazals for Tina

A Passing Bell: Ghazals for Tina Dry Milk

Dry Milk Toward the End

Toward the End Newcastle Sonnets

Newcastle Sonnets Turbulence

Turbulence Heide

Heide The Girls

The Girls Thorn

Thorn Benevolence

Benevolence Archival Poetics

Archival Poetics Where Only the Sky had Hung Before

Where Only the Sky had Hung Before Mother of Pearl

Mother of Pearl Blueberries

Blueberries A Constant Hum

A Constant Hum Everything Changes: Australian Writers and China, A Transcultural Anthology

Everything Changes: Australian Writers and China, A Transcultural Anthology The Pillars

The Pillars  We’ll Stand in that Place and Other Stories

We’ll Stand in that Place and Other Stories  Rethinking the Victim: Gender and Violence in Contemporary Australian Women’s Writing

Rethinking the Victim: Gender and Violence in Contemporary Australian Women’s Writing On Shirley Hazzard

On Shirley Hazzard  Beautiful Revolutionary

Beautiful Revolutionary Ashbery Mode

Ashbery Mode Milk Teeth

Milk Teeth My Van Gogh

My Van Gogh Damascus

Damascus Flood Damages

Flood Damages Sweatshop Women: Volume One

Sweatshop Women: Volume One Sleep

Sleep Yellow City

Yellow City Room for a Stranger

Room for a Stranger Infinite Threads

Infinite Threads Crow College: New and Selected Poems

Crow College: New and Selected Poems Sun Music

Sun Music On David Malouf

On David Malouf Traverse

Traverse Sergius Seeks Bacchus

Sergius Seeks Bacchus Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English Language

Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English Language The Grass Library

The Grass Library Prisoncorp

Prisoncorp Too Much Lip

Too Much Lip Lucida Intervalla

Lucida Intervalla Calenture

Calenture Stone Mother Tongue

Stone Mother Tongue Glass Life

Glass Life Vishvarūpa

Vishvarūpa out of emptied cups

out of emptied cups

Jungle Without Water and Other Stories

Jungle Without Water and Other Stories The short story of you and I

The short story of you and I The Red Pearl and Other Stories

The Red Pearl and Other Stories

Coach Fitz

Coach Fitz The Artist’s Portrait

The Artist’s Portrait Imminence

Imminence The Burning Elephant

The Burning Elephant Autobiochemistry

Autobiochemistry AXIS Book I: ‘Areal’

AXIS Book I: ‘Areal’

The Book of Thistles

The Book of Thistles  Rain Birds

Rain Birds Journey to Horseshoe Bend

Journey to Horseshoe Bend The Measure of Skin

The Measure of Skin

On Patrick White

On Patrick White  No Friend But The Mountains

No Friend But The Mountains

Mosaics from the Map

Mosaics from the Map No Country Woman: A Memoir of Not Belonging

No Country Woman: A Memoir of Not Belonging Dark Matters

Dark Matters Light Borrowers: UTS Writers’ Anthology 2018

Light Borrowers: UTS Writers’ Anthology 2018 Renga: 100 Poems

Renga: 100 Poems