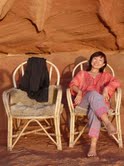

Louise McKenna

Louise McKenna was born in the UK where she completed a joint honours degree in English Literature and French. Her first poetry collection was A Lesson in Being Mortal (Wakefield Press 2010). She is co-editor of Flying Kites, the Friendly Street Reader 36, (Wakefield Press 2012). Her work has appeared in Poetrix and Eureka Street. Her work also features in Light and Glorie, an anthology of South Australian poetry forthcoming from Pantaenus.

With a rush of water

he reels the fish in,

light glancing off

the tessellation of mirrors

on its wet piscine skin.

In a flash he glimpses his son

writhing in a shawl of amnion,

his wife begging for oxygen

in her river of blood.

He unhooks the fish’s pleading mouth,

spills it over the bank

where the current swallows it

like a bolus of grief.

Beneath the meniscus

of his breathing world

the barb still hangs,

trails the air.

A Walk in the Post Natal Woods

A thatch of branches and fir cones

drains the sky, sieves nuggets of light.

In this moth-silent twilight

mushrooms flourish,

feeding on shadow.

Or blackberries,

sticky as blood clots.

I must carry my baby

from this bed of stone

with its lichen and moss,

its graveyard patinas.

Something malevolent

waits deep in the bole

of that tree.

I’ve heard these woods

are full of bears and witches.

I’m an easy target—

Gretel without Hansel

looking for exits

that appear and vanish

like holograms I tell the midwife.

In her eyes I see her shaking her head.

“With A Rush of Water“, was published in the Friendly Street anthology