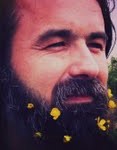

Dan Disney was born in 1970 in East Gippsland, where he grew up. He has worked in psychiatric institutions, paddocks, warehouses, and universities, and currently divides his time between Melbourne and Seoul, where he lectures in twentieth-century poetries at Sogang University. Articles and poems appear in Antithesis, ABR, Heat, Meanjin, New Writing, Overland, Orbis Litterarum, and TEXT, and poems have recently received awards in the Josephine Ulrick Poetry Prize (2nd) and the Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Prize (USA). He is on the advisory board of Cordite scholarly. His first full collection of poems, and then when the, was published by John Leonard Press in 2011.

‘only someone who already knows how to do something with it can significantly ask a name’

—— from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus

old buildings, falling out the sky

after the shriek of love leaves her body

I’m still there, a peasant and ass

laboring through dark hills toward the small bright windows

of infinity

meanwhile, afternoon seethes across a mechanical sky

the tzzz-ing of aircon

telling cicadas the rain

is a promised machine falling in pieces

‘don’t go’, I tell

her eyes darkly flicking, a slow

river in my shadow

listening to echoes deep in cold

mountains

(knee-high, green texta, weedy piss-stained carpark wall)

‘be the beauty you wish to see in the world’

I spent childhood in a hurricane. Hungry dogs wolved at the door.

Mother was an old television, father a fourth dimension. Had rain

fallen in downward lines, we’d have embraced and called it utopia

while deserts hurled themselves, sleeplessly, upon us

in the mind of the forest, the birds

are dreams tweeting rhapsodic operas. Flowers crane

their necks, louche

and metaphorical, while history looks on and falls

into place the way sunlight does. Morning is

thumping overhead, quipping ‘quieten!’ to the hives

chorusing a mist.

Thus the forest darkens, brightly

amid a copse of trees, ‘it’s not the flesh, drooped

and unblooming, but

our bones that groan so

beneath the slump of heaven’

the wooden temple amid hoarfrost. Her voice alone, is filled

with centuries. And when she talks, memories crowd

her bony feet and hop like chicks

(each sentence made of sunlight)

headline: ‘Bird of Paradise Cloned in Underworld

(Underworld Birds Not Happy)’

clutching the finger bones of dolls dreams

all the doors grinning

while night storms in: she’s there

in the corner of her lives

drinking the black

I was not there. The bird did nothing.

I was there pointing and the bird lifted and was then held out by air and this was called reality.

morning was a rain-smudged lens

focused into millennia

where strangers bent an early light

into shape

trailing the gloop of history indoors

new buildings, falling into the sky