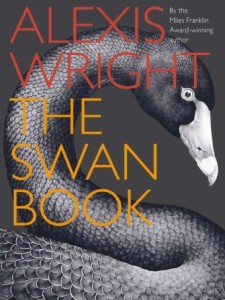

.jpg) Intimate Letters: Selected Poems of Chen Li

Intimate Letters: Selected Poems of Chen Li

translated by Chang Fen-ling

Bookman, Taipei

ISBN 9575866967

REVIEWED BY JANET CHARMAN

In November 2009 I was fortunate to be part of a group from around the Pacific Rim, attending the annual International Writers’ Workshop at Hong Kong Baptist University. Over the month of November each year, this programme introduces new writing to the university’s student body and to interested members of the public. And the writers themselves also encounter, amongst one another, texts and literary practices which are new to them.

Chen Li’s ‘Intimate Letters’ 1 was, to all intents and purposes, my introduction to recent poetry from his region. So although I don’t know how typical his work is; of either today’s Chinese poetics generally or Taiwanese poetry in particular; reading it alongside the Western work with which I am familiar, it struck me as utterly refreshing. And since, apart from the translator’s introduction, I have been able to find little specialist critical commentary on this remarkable material, I venture to make the notes that follow.

The poems in ‘Intimate Letters’ span twenty-one years in Chen Li’s writing life and contain work from the first six of at least ten published collections. Each poem is printed in Mandarin with an English translation on the facing page.

Chen Li is himself a prolific translator, (into Mandarin) of Western poets including among others, Neruda, Plath, Heaney, Larkin and Hughes; therefore his ease with European traditions may account for the climate of cultural affinity I experience when reading this work. Or, it could be that the poems’ wonderful immediacy, their, ‘rough play’, is a direct result of translator Chang Fen-Ling’s linguistic and literary acumen. In addition, her readings have a particular reliability since she is also Chen Li’s spouse.

But perhaps my greatest appreciation for Chen Li’s poetics arises from the fact that he supplies richly textured evocations of domestic life as the grounding for sophisticated readings in sexual and other sorts of politics: A perspective not generally prevalent in the writing of the male [New Zealand] poets of my experience: And for which female [New Zealand] poets may sometimes, still, be slighted. 2

Examples of working from “the domestic” can be found on almost every page of Chen Li’s collection. For example, a poem from 1976, ‘The Lover of the Magician’s Wife’ 3, records the surreal ‘breakfast scenery’ of an assignation where ‘The sun always rises from the other end of the eggshell in spite of the / strong smell of the moon.’

A 1989 poem about living in politically “interesting” times has: ‘Footsteps returning to every morning bowl of porridge. / Footsteps returning to the water of every evening washbasin’. 4 This poem takes the reader, in five unrhymed couplets and two singly placed lines, through the barely suppressed agitation of households trying to carry out the tasks of daily life, while gripped in listening hope and terror, for the return of their “disappeared”.

It’s the plainly stated images in the surrounding couplets that allow Chen Li to include the words ‘Rebelling against the foreign regime while ruled by it. / Raped by the fatherland while embracing it’ and have this read, not as polemic, but rather as an exactingly precise, and even bleakly ironic, statement of facts. That the charge of rape laid in these lines is couched as incestuous, serves once again as an example of Chen Li’s attachment to the domestic, the family, as the site of deepest social revelation.

‘February’ confronts the failure of a regime to represent its people by characterizing and then exposing that failing, as a ‘family matter’. A strategy that works against the tendency for a political apparatus or military chain of command, to detach leaders from their sense of personal responsibility for the human cost of their decisions. Whilst acknowledging the historical specificity attested to in the translator’s endnotes, it’s clear that ‘February’ could be read with equal understanding in Fallujah or Pyongyang, at Parihaka or in Manhattan.

And whereas the boundaries of family intimacy are here pierced by public acts of malice, the language of the poem equally denies sanctuary within the home, to perpetrators of private acts of abuse.

‘The Wall’ 5 was written a year later in 1990 and it also depicts the permeability of the membrane that separates the private and public worlds. It is a barrier on which characters lean through lives of muffled suffering. From a record of ‘The Wall’s’ eavesdropping on our human plight, the poem proceeds to describe the ways in which we imprint our dearly cherished identities onto it, in return. ‘Hanging on it is the clock / Hanging on it is the mirror’. “Attached” to the ‘The Wall’, these two ‘simple’ domestic appliances insinuate a sense of our fleeting mortality; linked to the eternal hope that we will ‘look the part’ even if we don’t deserve it.

The poem ends with the lines, ‘The wall has ears, / leading a giant existence sustained by our frailty.’ Despite the deployment of a phrase synonymous with totalitarian surveillance, the words which come immediately after, reveal that this is not an expression of hot defiance at the intrusion of “Big Brother”: Rather, the poem prefers a rueful acknowledgment of the structures of protection and nourishment one might expect from the dispassionate attentions of, say, ‘Big Mother’: ‘The Wall’ evolving towards a kind of scarily tender, uterine presence with whom the inhabitant of the room is both complicit and dismayed.

Manifestly not set in the hetero-normative king & queendoms of suburbia, the poem shakes out the social fabric of the high-density metropolitan: A location both protective and suffocating, in which privacy is revealed as a fiction sustained by the urban villagers’ compassionate or contingent belief in soundproofing.

What intrigues in this evocation and elsewhere in Chen Li’s work, is the complexity of the imagery. In the length of a line he habitually moves from the familiar, the aesthetically comforting, to points strange, inexorably foreign.

His prizewinning 1980 poem, ‘The Last Wang Mu-Qi’ also illustrates this tendency. The first lines read: ‘Seventy days, / we have stuck to the profound darkness, / listening to the coal strata talking with water. / The recycling quiet is everlasting as tapes, / playing back our breath in the minutest detail. / Roses between the lips, / maggots on the shoulders’. 6

This epic narrative is told in the voice of a coal-miner proletarian hero, a character whose consciousness over the course of the poem, ranges across Mainland China, ‘celebrating’ the works of man and nature. However, it is quickly revealed that this is also the voice of an entombed soul.

The changes Mu-Qi recounts take the reader from the rhythms of his subterranean shift at the coalface, across the bridge of terror into death. The poem deconstructs the explosion which leaves his body broken among those of his workmates: ‘ Intricate veins, / mysterious mother. / We are thus warmly immersed in great / geology. / Iron spades, coal carts, dynamites, fears / have all slipped along cordage of time into cobwebs of sleep.’ It enumerates with a kind of blackly comic yearning, the multiple aspirations he shared with his neighbours, dreams now to be fulfilled in his physical absence. And goes on to recount the specific ways in which ‘development’ may bring his own family previously unimaginable material wealth; but in the death of their husband and father, at a wholly unanticipated cost. The TV news noting the disaster, doesn’t even get his name right, so for a heartrending moment Wang Mu-Qi’s son believes someone else has taken his dad’s place in the apocalypse.

‘The Last Wang Mu-Qi’ manages its burden of bitter irony with a subversive slipping of tone between the gravity due to worker martyrdom in a ‘People’s Republic’; and the breathless elaboration of status enhancing material comforts from which the bereaved may take consolation: A thought that relieves Wang Mu-Qi nearly as much as it repels the implied reader. Balancing these tensions, as ever in Chen Li’s work, the meaning of this death is drawn from the deepest most private reaches of a particular family: ‘a nine year old child / I saw in a dream my dark-faced father return from the mine / and beat up Mother without saying a word. / A seventeen year old youth, / he watched confusedly his naked father / weeping secretly by the wall- / were you that young child too, when a black umbrella / sent the sister to a far away hospital / on a stormy night?’ 7

Throughout the poem Wang Mu-Qi seeks to make sense of what has befallen him, not just in death, but also in the inexplicability of the suffering he experienced in a life that he has had to leave so grotesquely unresolved. If the reader is rewarded with the narrative pleasures of an epic tragedy, they are also obliged to deal with its abrupt and ‘unsatisfactory’ termination. In his final advice to his widow, Mu-Qi says: ‘On such a dark and stormy night, don’t forget to bolt / all the doors and windows of the house…’ his best attempt at ‘closure’ frighteningly inadequate to the events that have overtaken him. Chen Li offers no final epiphanies in this brutal record of one man’s life and pointless death.

Elsewhere, in writing of vivid sensuality, husbands and wives, lovers, are given “room enough and time”, to fully communicate their emotions: ‘From the cup I drink the tea you pour for me, / from the cup I drink the spring chill flowing down / between your fingers.’ 8

This is a ‘modern’ Haiku, number twenty-six from a set of one hundred in the 1993 series ‘Microcosmos’, of which half are included in ‘Intimate Letters’. In these Chen Li has dispensed with the formal line length restrictions of the classical form, while retaining every particle of the electric shock that an aficionado of “the Haiku moment” might require. Number thirty-eight reads: ‘On the night cold as iron: / the percussion music of two bodies / which strike each other to make a fire.’ 9

In these two poems, and tellingly, in the absence of gender specificity, ‘simple’ domestic acts (fire lighting and pouring tea) are used to convey an intense eroticism. Many other pieces here, in both long and short poetic forms, render eros with equivalent poignancy. ‘Morning Blue’ is particularly notable for its evocation of lovers surfacing from jouissance into the prosaic “busynesse” of life: ‘your blue underwear, which is sought everywhere in vain / your blue hair ribbon, which is raised with the wind.’ 10 The narrator then appears to roam alone, in imagination, across the abandoned terrain of the dawn they’ve shared. Their profound physical engagement attracting deep anxiety about the loss of self on which, in retrospect, such an ecstasy is unavoidably predicated. So: ‘you contradict my thought / oppress my breath’. And: ‘You make me take the remainder of your saliva as the ocean / as the Mediterranean’: The beloved finally referred to as: ‘…goddess of evil, master of the morning.’

I read this last line as a manifestation of the patriarchally orchestrated unheimlich, which, as ever, kicks into life in the presence of a desired feminine ‘other’. But earlier in the poem, uncanny waves of terror are equaled by the exhilaration of tumultuous desire, voiced as if by someone swept ashore on an island “where the wild things are”. However, in the end this reader feels she has to swallow a summary rejection of the [voracious] feminine. That may close (if not resolve) the issue for a man: But it’s no coda for a woman. Despite this; in its tender and funny opening; its audacious, risk taking body text; and its fatally wounded and wounding (albeit culturally prescribed) final act of denial; the poem is one of the masterpieces of the collection.

The tone of other love poetry here ranges from the sublime understatement of ‘A Cup of Tea’: ‘At first hot, turned warm, and then cold.’ 11 To the anguished bravado of ‘Nocturnal Fish’: ‘Do you still boast of your freedom? // Come and appreciate a fish, appreciate a space fish that suddenly becomes rich / and free, because of your forsaking.’ 12

In ‘My Mistress’, 13 the collection’s first piece, from 1974, the narrator employs the conventional erotic trope of woman-as-guitar: Only to reveal, when the music begins, a destructive impairment of the player’s exquisite preparations, exposed in a tone of [willful] innocence: The chagrin of the ending like a dispatch from an outpost between theory and practice.

In the 1990 poem ‘An Intimate Letter’14 , the narration initially embraces a sensual decorum, composed from the intensely observed minutiae of a view from a window. Then the comfortable opening tone: ‘Youth, the sound of the chapel organ’ subtly shifts and with changes of dark to light observed in the street, there comes a registering of other memories: ‘the panting electric fan in a small hotel, / the street lamp sighing under the moon.’ The sense of a sexual anonymity, barely but exquisitely contained in these lines, is remarkable. From here, with the narrator’s awareness of corners left unturned and friends unmet, the poem’s focus pulling nostalgia is progressively destabilised. Out of a present that ‘brightens’: ‘broad’, ‘spacious’: comes a sudden recognition of doors at first opened and then shut. The narrator stands: ‘back to a set of half-dark wardrobes’: and examines a metaphor for a long abandoned aspect of the self: ‘You think of a scarf, not exactly ugly, / used in winter, forgotten in summer. / It occurs to you that a scarf is like a song, and a song / is a winding street.’ These incremental displacements lift the poem from initial conventionality, through ambivalence, to alert acceptance. And as it ends, the narrator buoyantly taking the stairs to the outside world, seems set to embrace both the light and shade of all he has lived through: And in so doing, to admit the past to the present.

Because of what’s been felt to achieve this resolute finish, the tensions raised in the poem remain acutely in play. It’s as if the public soul searching of a “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” were made to vibrate for a moment at the pitch of a private life: Yet the poem’s lightness of touch is an implicit indictment of all forms of compelled self criticism.

Appropriately, this poem is the one chosen to lend its register of artless simplicity to the collection’s title. However, despite its series of unassuming confidences ‘Intimate Letters’ makes no concessions in terms of aesthetic or intellectual complexity. Rather, the subtleties of the poems’ language strategies are directed to engage the reader in a series of unflinchingly personal reflections on the ethics of the public realm.

Intriguingly, ‘My Mistress’ and ‘An Intimate Letter’, depict a kind of dynamic musicality as inherent in our bodies as we interact with the world: ‘Then she tenses herself into a real / six stringed instrument, spreading intensely / her easily-ignited beauty.’ 15 Both are representative of the musicological strand present in Chen Li’s work generally. Another example: The 1992 poem, ‘The Bladder’, renders this organ as if it were a sort of art installation in the Len Lye kinetic tradition: An internal instrument that ‘…goes up and down, flickering and blinking’. 16

In this poem the social consequences of drinking are conciliatingly and wittily revealed in a hyper-aware depiction of their physical effects. However, elsewhere, such indulgences are treated with forensic acuity: In ‘Buffalo’, Officials from the north are, ‘Drinking tea, urinating, on the laboriously-carved dreams of the people’. 17 In ‘Travelling in the Family’: ‘[…] pressing her, beating / her, cursing her/ after drinking at midnight, leaving her washing the scars on her body / with her baby in arms.’ 18 This richly detailed inter-generational sequence, particularly registers with me in regard to its treatment of family violence: On which topic [New Zealand] poetry commonly maintains a speaking silence.

Chen Li’s depiction of social consequences can also be seen in his portrayal of indigeneity and colonialism. Many poems in the collection unpack the ethnic influences that constitute modern Taiwanese society, wrestling with complexities of language, nationality and colonizers’ identities: And looking to some extent at issues of culpability in displacing indigenous populations.

An example of the poet’s particular identity concerns can be found in ‘Green Onions’ where the issues are constituted, (again, typically) in terms of the domestic. A boy is sent out to buy green onions for his lunchbox: the ‘green onions smelling of mud. / When I got home, I heard the Holland peas in the basket / telling Mother in Hakka dialect that the green onions were brought / home.’ 19

The poem then proceeds through the child’s day at school, observing how he: ‘ate my lunch stealthily after every class’, and because of this, despite the welter of political indoctrination included in his lessons: ‘Counter-attack, counter-attack counter- / attack the Chinese mainland’: it is the taste of green onions, so entirely at home in his mother’s kitchen, that immunises him against propaganda; and leads him to the realization that he does have a ‘place to stand’, a personal geographic location with which his identity is profoundly engaged. This small, sunlit, kitchen moment, is posed as a counterpoint to the poem’s dizzying seven-line evocation of the narrator’s cross-continental journey to the ‘vast Green-Onion Mountain Range’: The poem as effective at drawing the unfathomable immensities of the world into its own ‘small’ frame; as the little green onion is at revealing to the narrator the truest sources of his identity.

Chen Li’s assertion here that cultural weight is estimable not in size, but in substance, is further amplified in his 2010 essay, ‘Travelling Between Languages: Possessed by Chinese characters.’ 20 The article is an expression of dismay that the sophistication of Chinese literature may ultimately be diluted by the Mainland’s use of a modified text in Putonghua, which standardises the simplification of characters written in Mandarin.

However, it’s not possible to read this essay from an entirely linguistic perspective since Chen Li also suggests, from his position as a seeming outlier, that the classical complexity retained in Taiwan’s written language, positions the Taiwanese as in some sense more ‘Mainland’ than the mainland. That the piece appears in an edition of the American journal Poetry, also locates these issues within the framework of ‘superpower’ debate over competing imperialist claims on Taiwan: Whose citizens respond by asserting (whilst spending enormous sums of money on arms from the US) their unassailable sovereignty.

The ambivalence inherent in such alliances and the issues of authenticity of identity they raise, are cuttingly, if comedically addressed in Chen Li’s 1994 poem ‘English Class’ 21 which skewers the cultural presumption implied in the phenomenon of the monolingual English teacher. Chinese students’ English language acquisition here revealed as yet another strand in a long history of Western colonization. A poem also alert to the irony that, (as the biographical notes in ‘Intimate Letters’ attest) Chen Li has himself taught English in various settings, throughout his working life.

Here, as elsewhere, Chen Li’s poetics destabilise polemical confrontation by refracting contentious issues through the personal and the domestic. Not with the effect of diffusing or diminishing the importance of such issues, but rather by reframing the private sphere; the self, the home; as a site in which one may engage deeply with; rather than detach from; such concerns: A setting in which avante garde art practice may effectively interrogate realpolitik.

To the extent that poetry under patriarchal capitalism has resisted commodification, the reconfiguration of domestic spaces and personal privacy in writing such as Chen Li’s, is potentially the antithesis of bourgeois retreat: A resistant rootstock, which in the age of digital communication offers some interesting alternatives to the bankrupt discourses of perpetual economic growth.

The presumption of marginality or triviality for such poetic strategies is neatly challenged in the following extract from ‘A Vending Machine for Nostalgic Nihilists’22. A poem whose iconoclastic menu bullet points the ‘hot button’ issues of a generation of thwarted activists: ‘Sleeping pill *for vegetarians *for non-vegetarians // Misty poetry *two pieces in one *three pieces in one *aerosol // Marijuana *of Freedom brand *of Peace brand *of Opium War brand // Condom * for commercial use * for non-commercial use’: And in so doing refutes the idea that a poetics closely attuned to the ‘everyday’ experiences of commuter consumers snacking their way home from work, must, by definition, be inadequate to the political challenges of “serious” art.

The poem’s unconventional ‘listing’ structure amplifies its theme that all authorities, no matter how professedly liberal or artistic, can be questioned. In this respect its reference to ‘Misty poetry’ bears closer examination. On the mainland, in the late seventies, the writers identified with this label, produced work whose calculatedly anarchic forms both exposed and temporarily evaded the crippling cultural restrictions that eventually resulted in their banning. Chen Li’s line sketches ‘Misty’ poetry’s progress through linguistic condensations of existential extremity, to ‘aerosol’. Aptly suggesting the persuasiveness of ideas invisible to “The Authorities” but accessible to anyone else with a nose. Yet ‘aerosol’ also sounds a dismissive note, perhaps understandable in a writer not bound to subterfuge: someone brave, reckless or lucky enough, to be able to call a spade a spade: Chen Li himself handy with a ‘digging implement’ when necessary.

Great art may be constructed in extremis, but more often it is ground under the heel of the dictator. So in our “interesting” times if we think we have the right to free speech, such a belief needs to be tested. Chen Li does voice the concerns of people who might otherwise be rolled under the ‘big wheels’ of history. And while the ‘homely’ strategies of his poetics merit broader theoretical consideration, this is not to deny that his work could be read in many other ways. A diversity of approaches to issues of sustainability in contemporary life has never been more important. Think global: Act local.

I found Chen Li’s poem ‘Adagio’23 on the web and since it was written in 2006, it does not appear in the collection under discussion here. Nevertheless I will refer to it in this essay because I hope it may signal future directions in Chen Li’s writing. Specifically its compositional strategies link it to the series of ‘concrete’ poems 24 that appear towards the end of ‘Intimate Letters’. In this work, form follows function in terms of ideographic representation: However, the thematic concerns of ‘Adagio’ are ‘concretely’ expressed in a use of repetition.

The poem begins, ‘Grandma sitting by the window’, her seventeen-year-old self, poised watching cloudscapes and waiting for her future: As an old woman, that long ago “cloud gathering” descends to her head both in the changed colour of the ‘cloud’ of hair she sees in the mirror and in the form of her mystifying perception of time. The compassion and economy with which the poem evokes this complex progression in the character’s life, is remarkable.

Looking through her eyes, her grandson walks across the lawn to the house in which she sits, watching him cross the lawn. In this cycle of seeing and being seen both are connected to the energy of the instant. The reader simultaneously bound into the richly detailed imagery of Grandma’s sequestered intelligence: ‘The oriental sesame flower stands / at the other end of the lawn / chit-chatting with her sisters / Grandma thinks to herself / the silent tree is poetry / so is the talking flower / She raises her head and sees me’ The enjambment in these lines reveals the complexity of a “female gaze” presumed to encompass the independent witness of the protagonist’s grandson.

And conveying a refreshing subjectivity further amplified when, in this first section of the poem: ‘She turns on the radio / to listen to reports of snow / but the grass is so green / Suddenly she craves / vanilla ice cream’. The intensity of this description a particular novelty to the extent that our cultures commonly deny sensual pleasure to the old: privileging the young.

Then starting into the second section, a shock of realisation awaits the reader since although entirely new features of the narrative flow into view; paradoxically these perceived changes arise from a repetition of precisely the same words: Here Chen Li makes manifest a twist on the ancient philosophical truth that “you cannot step into the same river twice”. As the poem’s ending cues the reader to start again from the beginning, the poem also suggests this metaphor of seemingly perpetual change, may also be read as part of a deeper cycle of eternal renewal.

I read Chen Li’s innovative use of repetition as coming from a feminine jurisdiction, by referencing an essay of the English novelist Rachel Cusk’s, that appeared in The Guardian Weekly in response to the publication of new editions of Virginia Woolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own’ and Simone De Beauvoir’s ‘The Second Sex’.

‘A Voice of Her Own’, 25 discusses the pressure on writers to abandon ‘the book of repetition’, if they wish their work to be taken “seriously” and to adopt instead the literary style of ‘the book of change.’ The latter can be summarised as a narrative model whose effect is to impoverish literary representations of women’s sexualities by preferring that only male centered discourses be considered as “serious” art: the texts most worthy of critical notice and canonical inclusion.

However, I understand ‘Adagio’, as opening the ‘book of repetition’, to reveal a ‘book of change’ that may be read concurrently. The poem, in these terms, deprived of essentialist tropes of either femininity or masculinity: Its ‘change’ situated, not in the text its-self, but rather in the construction of a reader freed of their assumptions (conscious or otherwise) about the superiority of ‘masculine’ over ‘feminine’ narratives.

Yes, the poem is repetitive, but that does not make it inferior. Its narrator embraces the cyclic way [an old] woman sees the world: affirming both her physiological representation of time and her unique cultural perspective. A recycling of the text which both exposes and counters the reader’s culturally condoned tendency to dismiss or trivialise her.

The poem’s language of Arcadian serenity (distant clouds, green grass) conditioned my first impression. However, the text’s subsequent re/presentations provoke an involuntary re-evaluation. When ‘A cat walks across the lawn’ and accidentally ‘knocks over the rattan chair’ it triggers a consciousness that the ‘pig’ that once dominated Grandma’s field of vision; was responsible for intentionally knocking over other “things”: ‘but not now’. As ‘She turns on the radio’ the poem overrides an embedded memory of pain. The narrative’s onward momentum, determinedly recognising the abuse Grandma endured, yet perpetually reinstating her in the garden as a self-determining subject: Someone who sees the world on her own terms and who can choose to occupy ‘the middle of the lawn’.

Such an innovative use of repetition might also cue the reader to think about more conventional ‘change’ cultures, for example in institutions [narratives] where successfully realised masculinity is synonymous with relentless ‘development’ [plotting]. Such approaches potentially destructive not only for those whose social disposition is towards co-operative models [as revealed, say, in the ‘microclimate’ of this poem] but also for the healthy functioning of other ecosystems that we share.

Yet, given the chance, as Rachel Cusk’s essay ably demonstrates, we women have shown ourselves to be as adept as the next apparatchik at the [literary] ventriloquisms, which close ‘the book of repetition’ in favour of ‘change’ narratives allowing us to “pass” as honorary patriarchs. If such a co-option is an ever present temptation for a woman, how much more seductive is it for a man? Wherever his position of superiority becomes visible, we are encouraged by the hegemonic tendencies in our cultures to read his preferment as ‘natural’.

The refusal of such abject identifications is what makes the feminist project for sustainable social and ecological practices meaningful. However, in all probability what will be needed for such a project’s success is the concurrent emergence of a masculinist project whose goals (whatever they may be) are synchronous. With that thought in mind I read ‘Adagio’s’ tricky, transgressive narrative, as contributing towards such a contingency.

Throughout ‘Intimate Letters’ the changes Chen Li’s protagonists undergo may be read as occurring with, rather than against, the tidal currents of the feminine: Particularly in the sense that his work depicts the quest for mature identity as being less about leaving home and more about finding the courage to invite the world in: ‘Joy is a hole: / tuck an object in, and out flow / fruit-like vowels.’26

The ‘Microcosmos’ in, and beyond the Haiku in the pages of ‘Intimate Letters’, are peopled with ‘minor’ identities whose vividly sketched individuality can be read as testimony against patriarchally ascribed abjection. Yet, paradoxically, the writer who finds inspiration in somebody [seemingly] with nothing to lose, voices that marginalised subject, as s/he would not dare to express herself. The poet’s authority to make pronouncements implying a position of rightful privilege: ‘In a city alarmed by a series of earthquakes / I saw pimps on their knees returning vaginas to their daughters.’ 27 Her lack ‘necessitating’ that s/he is spoken for: Chen Li’s very eloquence, here reifying his character’s inarticulacy. This is unsupportable.

Chen Li is himself alert to these implications and can be said to address them in his poem ‘The Image Hunter’, 28 which presents a series of violent scenarios and asks how an artist engaging with them, may: ‘move slowly, restrain the sense of guilt… / [.] / so as to present the world with true and grievous art’. Seeming to resolve, in the arresting ambivalence of the poem’s conclusion, that the poet ‘…making fruit slack enough to flow out / juice’; 29 must bear the consequences of framing questions they can’t answer: But this seems too much like “man’s” work to me.

Elsewhere, a wilful humbling of his own authority can be gathered from Chen Li’s joyous evocations of the natural world: Not magisterially descriptive, a voice nakedly exposed to the exigencies of our contestable human habitats: wordquakes, urgently summoning the reader, with the writer, to the kettle, to the precipice, of our own known worlds. Where ‘we watch the cold river boiling once again, / warmly dissolving the descending darkness’. 30

I wait impatiently for more translations.

Here, to close, the last four “open” lines of Chen Li’s 1995 poem ‘Furniture Music’ 31:

‘In the songs that I hear

In the words that I say

In the water that I drink

In the silence that I leave’

Notes

1.Several of Chen Li’s poems have won literary prizes, both in Taiwan, his home, and in China. The biographical notes in the collection also record that in 1993 ‘Intimate Letters’ received Taiwan’s National Award for Literature and Arts. In addition, Chen Li’s web page: http://www.hgjh.hlc.edu.tw/~chenli/selectedpoems.htm: notes his appearance as guest reader at a number of distinguished international forums.

2.‘When Life Happens in more dramatic ways, the poems get more compelling; a series of poems on Livesey’s ageing, and ailing, mother are often very moving. But there seems little to compel the reader’s interest in them as poems beyond the human interest of the story they tell. A cracking irregular villanelle, ‘Chrysalis’, shows that Livesey is capable of far richer formal investigations, and more arresting imagery than she risks elsewhere in this collection.’

[…]

‘The poems explicitly exploring this dark passage in her life are riveting, in their way: how could a poem from a mother to her children imagining their response to her own death be anything but? However, these are perhaps not the most successful poems in this striking debut. Unsurprisingly, there is in these works what Wordsworth called an “overflow of powerful feelings” but not quite, yet, that transformation by reflective “tranquillity” that would sublimate these feelings into a fully realised work of art.’

Roberts, Hugh, ‘Is it a poem or a blog?’ NZ Listener, Arts & Books, July 31-August 6, 2010 Vol. 224 No 3664: The full text can be read at:

http://www.listener.co.nz/issue/3664/artsbooks/15877/is_it_a_poem_or_a_blog.html

3.‘The Lover of the Magician’s Wife’: Chen Li, Intimate Letters: Selected Poems of Chen Li, 1974-1995: Translated and Introduced by Chang Fen-Ling: Bookman Books, Taipei, 1997, p. 47

4.‘February’, ibid, p.103

5. ‘The Wall’, ibid, p.201

6. ‘The Last Wang Mu-Qi’, ibid, p.163

7. ibid, p.173

8. Haiku 26, [from: Microcosmos] Intimate Letters, p. 245

9. Haiku 38, ibid, p.246

10.‘Morning Blue’, Intimate Letters, p.271

11. ‘A Cup of Tea’, ibid, p.263

12. ‘Nocturnal Fish’, ibid, p. 277

13. ‘My Mistress’, ibid, p.37

14. ‘An Intimate Letter’ ibid, p.199

15. ‘My Mistress’, ibid, p.37

16. ‘The Bladder’, ibid, p.209

17. ‘Buffalo’ ibid, p. 127

18.’ Travelling in the Family’, ibid, p. 187

19. ‘Green Onions’, ibid, p.123

20. ‘Travelling Between Languages: Possessed by Chinese Characters’

Chen Li @ www.poetryfoundation.org/journal/article.html?id=238868

21. ‘English Class’, ‘Intimate Letters’, p. 281

22. ‘A Vending Machine for Nostalgic Nihilists’, ibid, p. 213

23.‘Adagio’, World Literature Today, Contemporary Taiwanese Poetry:

http://wlt.metapress.com/content/r389532558287x41/

24. Concrete poems are another significant aspect of Chen Li’s poetics. A particularly effective example is: ‘A War Symphony’, Intimate Letters, p. 286. In this piece the ideograph for ‘soldier’ marches across several pages of text, progressively losing, left and right, its glyph ‘limbs’: (“兵”, “乒”, “乓”, “丘”) The effect is that in their progressively reduced forms the second and third ideographs above, can be read as explosive ‘combat’ sounds, and finally, as seen in the fourth ideograph, the original ‘soldier’: “兵”, is ‘cut down to size,’ as: “丘”. This is also the ideograph for ‘small hill’, which, in the blackest of ironies, may also be read as ‘burial place’. An extraordinary animation of the poem can be viewed on line at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vKJumF5Rdok

The written text can be viewed with an audio of Chen Li performing it, at: http://www.hgjh.hlc.edu.tw/~chenli/WarSymphony.htm

NB: In ‘Intimate Letters’ Chen Li’s poems have left justified margins. On his website however (and in this reader’s view, with a consequent loss in visual fluency) his work (excepting the ‘concrete’ poems) is ‘centered’: As are the poems he has translated.

25. Cusk, Rachel, ‘A Voice of Her Own’,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/dec/12/rachel-cusk

26. Haiku 27, [from: ‘Microcosmos’] ‘Intimate Letters’, p. 245

27. ‘In a City Alarmed by a Series of Earthquakes’, ibid, p.73

28. ‘The Image Hunter’, ibid, p.302. This piece, from 1994, is subtitled ‘in memory of Kevin Carter’. A note to the poem explains that this photographer committed suicide not long after he was criticized for taking a Pulitzer prize winning shot of a vulture waiting to settle on the living body of a malnourished young girl, at the point of death in a Sudanese desert. Instead of engaging with her he chose to represent her plight: as ‘art’.

29. ibid. p.303

30. ‘The River of Shadows’, Intimate Letters, p. 215.

31.‘Furniture Music’, ‘Intimate Letters’, p. 305

JANET CHARMAN has an MA 1st. Class Hons. from Auckland University. She has published seven collections of poems and was granted the New Zealand Annual poetry award for her 2008 collection Cold Snack. She has been a visiting creative writing fellow at AU and HKBU. Her most recent collection of poems At the White Coast, appeared from AUP in 2012.

Vesna Goldsworthy (1961, Belgrade) lives in London and writes poetry in English, her third language, as well as her native Serbian, in which her poetry is much-anthologized. Aged twenty-three, she read her poems at a football stadium to an audience of thirty thousand people. She moved to Britain soon afterwards and did not write a line of poetry for over twenty years. Her Crashaw Prize winning debut poetry collection in English, The Angel of Salonika (Salt, 2011) was one of the Times Best Poetry Books of the Year.

Vesna Goldsworthy (1961, Belgrade) lives in London and writes poetry in English, her third language, as well as her native Serbian, in which her poetry is much-anthologized. Aged twenty-three, she read her poems at a football stadium to an audience of thirty thousand people. She moved to Britain soon afterwards and did not write a line of poetry for over twenty years. Her Crashaw Prize winning debut poetry collection in English, The Angel of Salonika (Salt, 2011) was one of the Times Best Poetry Books of the Year.

Barnacle Rock

Barnacle Rock

Brenda Saunders is a Sydney poet of Aboriginal and British descent. She has published three collections of poetry, her most recent, The Sound of Red (Ginninderra Press, 2013). Her work has also featured in anthologies and journals and was included in Best Australian Poems 2013 (Black Inc.) In 2013 she was awarded a Resident Fellowship to CAMAC Arts Centre in France where she worked translating into her poetry into French.

Brenda Saunders is a Sydney poet of Aboriginal and British descent. She has published three collections of poetry, her most recent, The Sound of Red (Ginninderra Press, 2013). Her work has also featured in anthologies and journals and was included in Best Australian Poems 2013 (Black Inc.) In 2013 she was awarded a Resident Fellowship to CAMAC Arts Centre in France where she worked translating into her poetry into French. Joel Ephraims lives on the South-East Coast of NSW. He studies creative writing, philosophy, and literature at the University of Wollongong. In 2011 he won the Overland Judith Wright Poetry Prize and in 2013 his chapbook of poetry, Through The Forest was published as part of Australian Poetry and Express Media’s New Voices Series.

Joel Ephraims lives on the South-East Coast of NSW. He studies creative writing, philosophy, and literature at the University of Wollongong. In 2011 he won the Overland Judith Wright Poetry Prize and in 2013 his chapbook of poetry, Through The Forest was published as part of Australian Poetry and Express Media’s New Voices Series.  The Question of Red

The Question of Red

Autumn Royal is a poet and PhD candidate at Deakin University. Autumn’s writing has appeared in publications such as Antipodes, Cordite, Rabbit, and Verity La.

Autumn Royal is a poet and PhD candidate at Deakin University. Autumn’s writing has appeared in publications such as Antipodes, Cordite, Rabbit, and Verity La.

Saba Vasefi is a poet, a documentary filmmaker and human rights activist. She was a lecturer in Tehran, Shahid Beheshti University. She became a member of the Committee of Human Rights Reporters. She also worked as a reporter for the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. She was twice a judge for the Sedigheh Dolatabadi Book Prize for best literature on women’s issues. She was expelled from the University after 4 years of teaching due to her activism. Her documentary film about child execution in Iran ”Don’t Bury My Heart” has been screened for the BBC, United Nation, Amnesty International, The Copenhagen International Film Festival, SOAS university, University of Oslo, Dendy Opera Quays cinema and Seen & Heard Film Festival. She has published poems, research papers, articles, reports, interviews and multimedia about executions, censorship, and women and children’s rights. Her multimedia piece, “Shirin, A Soloist in the Silence Room” was screened in Geneva for the UN. She has also had work published in the anthology “Confronting the Clash: The Suppressed Voices of Iran. She was director of First Sydney International Women’s Poetry Festival (Woman Scream). Currently; she is completing a postgraduate degree in documentary at The Australian Film TV and Radio School (AFTRS).

Saba Vasefi is a poet, a documentary filmmaker and human rights activist. She was a lecturer in Tehran, Shahid Beheshti University. She became a member of the Committee of Human Rights Reporters. She also worked as a reporter for the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. She was twice a judge for the Sedigheh Dolatabadi Book Prize for best literature on women’s issues. She was expelled from the University after 4 years of teaching due to her activism. Her documentary film about child execution in Iran ”Don’t Bury My Heart” has been screened for the BBC, United Nation, Amnesty International, The Copenhagen International Film Festival, SOAS university, University of Oslo, Dendy Opera Quays cinema and Seen & Heard Film Festival. She has published poems, research papers, articles, reports, interviews and multimedia about executions, censorship, and women and children’s rights. Her multimedia piece, “Shirin, A Soloist in the Silence Room” was screened in Geneva for the UN. She has also had work published in the anthology “Confronting the Clash: The Suppressed Voices of Iran. She was director of First Sydney International Women’s Poetry Festival (Woman Scream). Currently; she is completing a postgraduate degree in documentary at The Australian Film TV and Radio School (AFTRS). Deb Matthews-Zott has published two collections of poetry, Shadow Selves (2003) and Slow Notes (2008). She runs the Australian Poets’ Exchange Facebook Group, which has a membership of over 800, and is convener of SPIN (Southern Poets and Musicians Interactive Network). ‘The Weir’ and ‘The Pug Hole’ are from her verse novel in progress, ‘An Adelaide Boy’.By day she is a Librarian.

Deb Matthews-Zott has published two collections of poetry, Shadow Selves (2003) and Slow Notes (2008). She runs the Australian Poets’ Exchange Facebook Group, which has a membership of over 800, and is convener of SPIN (Southern Poets and Musicians Interactive Network). ‘The Weir’ and ‘The Pug Hole’ are from her verse novel in progress, ‘An Adelaide Boy’.By day she is a Librarian. sean burn’s third and latest full volume of poetry is that a bruise or a tattoo? (isbn 9781848612945)

sean burn’s third and latest full volume of poetry is that a bruise or a tattoo? (isbn 9781848612945)

Nathan Curnow lives in Ballarat and is a past editor of Going Down Swinging. His work features in Best Australian Poems 2008, 2010 and 2013 (Black Inc) and has won a number of awards including the Josephine Ulrick Poetry Prize. His most recent collection, RADAR, is available through

Nathan Curnow lives in Ballarat and is a past editor of Going Down Swinging. His work features in Best Australian Poems 2008, 2010 and 2013 (Black Inc) and has won a number of awards including the Josephine Ulrick Poetry Prize. His most recent collection, RADAR, is available through

Toby Davidson is a West Australian poet, editor and reviewer now living in Sydney where he is an Australian Literature researcher at Macquarie University. He is the editor of Francis Webb Collected Poems (UWA Publishing ) and author of the critical study Christian Mysticism and Australian Poetry (Cambria Press). His debut poetry collection is Beast Language (Five Islands Press).

Toby Davidson is a West Australian poet, editor and reviewer now living in Sydney where he is an Australian Literature researcher at Macquarie University. He is the editor of Francis Webb Collected Poems (UWA Publishing ) and author of the critical study Christian Mysticism and Australian Poetry (Cambria Press). His debut poetry collection is Beast Language (Five Islands Press).

Ron Pretty’s eighth book of poetry, What the Afternoon Knows, was published in 2013. An updated edition of Creating Poetry will be published later this year. He spent six months in Rome in 2012, on a residency granted by the Australia Council.

Ron Pretty’s eighth book of poetry, What the Afternoon Knows, was published in 2013. An updated edition of Creating Poetry will be published later this year. He spent six months in Rome in 2012, on a residency granted by the Australia Council. Mario Licón Cabrera (1949) is a Mexican poet and translator living in Sydney since 1992, he has publishe four collectios of poetry and has translated many Australian leading poets into Spanish . He’s currently conducting a Creative Writing and Reading workshop (in Spanish) at The nag’s head hotel, in Glebe, NSW every first Saturday of each month.

Mario Licón Cabrera (1949) is a Mexican poet and translator living in Sydney since 1992, he has publishe four collectios of poetry and has translated many Australian leading poets into Spanish . He’s currently conducting a Creative Writing and Reading workshop (in Spanish) at The nag’s head hotel, in Glebe, NSW every first Saturday of each month. Born and raised in Singapore, Jonathan has worked and lived in Berlin and London. He once bungee-jumped and climbed a volcano to reason out the meaning of life. He is currently cobbling together his first collection of short stories. His stories have appeared in The Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, The Literary Yard (India), New Asian Writing, BananaWriters and Fat City Review.

Born and raised in Singapore, Jonathan has worked and lived in Berlin and London. He once bungee-jumped and climbed a volcano to reason out the meaning of life. He is currently cobbling together his first collection of short stories. His stories have appeared in The Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, The Literary Yard (India), New Asian Writing, BananaWriters and Fat City Review. William Byrne is a South Australian poet in his twenties. He has always lived in rural and coastal townships, excluding an urban interlude for university study for degrees in architecture and design.

William Byrne is a South Australian poet in his twenties. He has always lived in rural and coastal townships, excluding an urban interlude for university study for degrees in architecture and design. Hazel Smith is a research professor in the Writing and Society Research Centre at the University of Western Sydney. She is author of The Writing Experiment: strategies for innovative creative writing, Allen and Unwin, 2005 and Hyperscapes in the Poetry of Frank O’Hara: difference, homosexuality, topography, Liverpool University Press, 2000. She is co-author of Improvisation, Hypermedia And The Arts Since 1945, Harwood Academic, 1997 and co-editor with Roger Dean of Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts, Edinburgh University Press, 2009. She is co-editor with Roger Dean of soundsRite, a journal of new media writing and sound, based at the University of Western Sydney.

Hazel Smith is a research professor in the Writing and Society Research Centre at the University of Western Sydney. She is author of The Writing Experiment: strategies for innovative creative writing, Allen and Unwin, 2005 and Hyperscapes in the Poetry of Frank O’Hara: difference, homosexuality, topography, Liverpool University Press, 2000. She is co-author of Improvisation, Hypermedia And The Arts Since 1945, Harwood Academic, 1997 and co-editor with Roger Dean of Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts, Edinburgh University Press, 2009. She is co-editor with Roger Dean of soundsRite, a journal of new media writing and sound, based at the University of Western Sydney. Dimitra has a Bachelor of Performance Studies from the University of Western Sydney – Theatre Nepean, and a Master of Letters in Creative Writing from University of Sydney. She’s had poems published in Australian Poetry’s Members’ Anthology, Meanjin, and Southerly. In 2012 she won the Australian Society of Author’s Ray Koppe Young Writers Residency.

Dimitra has a Bachelor of Performance Studies from the University of Western Sydney – Theatre Nepean, and a Master of Letters in Creative Writing from University of Sydney. She’s had poems published in Australian Poetry’s Members’ Anthology, Meanjin, and Southerly. In 2012 she won the Australian Society of Author’s Ray Koppe Young Writers Residency.

.jpg) Intimate Letters: Selected Poems of Chen Li

Intimate Letters: Selected Poems of Chen Li

Born on Wakka Wakka land at Barambah, which is now known as Cherbourg Aboriginal Reserve, Lionel Fogarty has travelled nationally and internationally presenting and performing his work. Since the seventies Lionel has been a prominent activist, poet writer and artist; a Murri spokesperson for Indigenous Rights in Australia and overseas. His poetry art work and oral presentation illustrates his linguistic uniqueness and overwhelming passion to re-territorialize Aboriginal language culture and meaning which speaks for Aboriginal people of Australia. In 2012 he received the Scalon Prize for Connection Requital and his most recent collection is

Born on Wakka Wakka land at Barambah, which is now known as Cherbourg Aboriginal Reserve, Lionel Fogarty has travelled nationally and internationally presenting and performing his work. Since the seventies Lionel has been a prominent activist, poet writer and artist; a Murri spokesperson for Indigenous Rights in Australia and overseas. His poetry art work and oral presentation illustrates his linguistic uniqueness and overwhelming passion to re-territorialize Aboriginal language culture and meaning which speaks for Aboriginal people of Australia. In 2012 he received the Scalon Prize for Connection Requital and his most recent collection is

Christopher Pollnitz’s Little Eagle and Other Poems was a Wagtail publication in 2010, and his six “American Idylls” were in Mascara 11. He has written criticism of Judith Wright, Les Murray, Alan Wearne and John Scott, as well as D. H. Lawrence, and been a reviewer for Notes and Queries and Scripsi, as well as The Australian and Sydney Morning Herald. His edition of The Poems for the Cambridge University Press series of Lawrence’s Works appeared in 2013.

Christopher Pollnitz’s Little Eagle and Other Poems was a Wagtail publication in 2010, and his six “American Idylls” were in Mascara 11. He has written criticism of Judith Wright, Les Murray, Alan Wearne and John Scott, as well as D. H. Lawrence, and been a reviewer for Notes and Queries and Scripsi, as well as The Australian and Sydney Morning Herald. His edition of The Poems for the Cambridge University Press series of Lawrence’s Works appeared in 2013. Benjamin Dodds is a Sydney-based poet whose work appears in a variety of journals and magazines. Two fun factoids: (1) Benjamin collects Mickey Mouse watches, and (2) his first collection, Regulator, will be published by Puncher & Wattmann in early 2014.

Benjamin Dodds is a Sydney-based poet whose work appears in a variety of journals and magazines. Two fun factoids: (1) Benjamin collects Mickey Mouse watches, and (2) his first collection, Regulator, will be published by Puncher & Wattmann in early 2014. Liang Yujing writes in both English and Chinese, and is now a lecturer, in China, at Hunan University of Commerce. His publications include Willow Springs, Wasafiri, Epiphany, Boston Review, Los Angeles Review, Bellevue Literary Review, and many others.

Liang Yujing writes in both English and Chinese, and is now a lecturer, in China, at Hunan University of Commerce. His publications include Willow Springs, Wasafiri, Epiphany, Boston Review, Los Angeles Review, Bellevue Literary Review, and many others. Zuo You is a Chinese poet based in Xi’an. His poems have appeared in some major literary magazines in China. He is hearing-impaired and can only speak a few simple words.

Zuo You is a Chinese poet based in Xi’an. His poems have appeared in some major literary magazines in China. He is hearing-impaired and can only speak a few simple words. Zeina Issa is a Sydney based interpreter and translator, a columnist for El-Telegraph Arabic newspaper and a poet.

Zeina Issa is a Sydney based interpreter and translator, a columnist for El-Telegraph Arabic newspaper and a poet.