Stu Hatton reviews “Devadatta’s Poems” by Judith Beveridge

by Judith Beveridge

ISBN 978-1-922146-52-6

Reviewed by STU HATTON

According to the collection of Buddhist scriptures known as the Pāli Canon, Devadatta was a first cousin of the Buddha. Devadatta created a schism within the Sangha (the Buddha’s order), and tried to murder the Buddha on several occasions. In her introduction to Devadatta’s Poems, Judith Beveridge writes:

Some commentators say that Devadatta was the brother of Yasodhara, Siddhattha’s [i.e. the Buddha’s] wife, but I have also read that Devadatta was a suitor to Yasodhara, but he failed to win her hand in a test of arms, and that part of Devadatta’s animosity towards the Buddha was based on jealousy (p. 3).

Beveridge takes the latter version of the tale and runs with it, casting Devadatta as the speaker/poet in a book-length sequence of 48 monologues that she is quick to label as ‘highly fictionalised and dramatised’ (Introduction, p. 3; Beveridge’s emphasis). Here it’s worth noting Buddhist scholar and teacher Reginald Ray’s contention that ‘within the Indian Buddhist corpus’, portrayals of Devadatta are ‘not entirely consisent’, ranging from his being synonymous with evil, to being a saint praised by the Buddha himself (Ray, p. 162). Although Ray’s argument has been criticised in some quarters (see, for example, Bhikkhu Sujato), nevertheless as a mytho-historical figure, Devadatta’s status is unresolved to a certain extent, and this can be seen to offer Beveridge considerable licence.

The book’s title attributes the poems to Devadatta, but of course this is still very much a collection of Judith Beveridge poems. Had it been published anonymously, it would surely have been obvious to dedicated readers of her poetry that this was a Beveridge collection, partly due to hallmarks of style and form. The Buddhist subject matter would also have been a significant clue, since this is not the first time she has traversed this territory. Her 1996 collection Accidental Grace has a short sequence entitled ‘The Buddha Cycle’; and Wolf Notes (2003) includes ‘Between the Palace and the Bodhi Tree’, a longer sequence in which Siddhattha is cast as the ‘I’, tracing the time from when he adopts a mendicant life, up until he is about to attain enlightenment.

Devadatta’s poems tend towards a formal neatness: most have a set number of lines per stanza, and some of the shapelier stanzas use indents with regular patterns. There are a number of variations on the pantoum—whereas ‘Between the Palace and the Bodhi Tree’ offered variations on the stricter, more exacting villanelle. Repetition, simile, alliteration, assonance and rhyme are key linguistic components of the Pāli Canon (see Bhikkhu Anālayo), and all feature in Devadatta’s Poems. Alliteration and assonance are pushed to the limit in ‘Ground Swell’ (p. 8), in phrasings such as ‘the swippling swishes of fly-maddened flails’. Rhyme is employed occasionally, in poems such as ‘In Rajagaha’ (p. 28) and ‘Nightmare’ (p. 44). The concluding rhymes of ‘trash’/‘panache’/‘hash’ in ‘The Hermit’ (p. 48) examplify the humour that invigorates much of the collection.

Repetition comes to the fore in ‘Tailspin’ (p. 19), where practically every word or phrase is repeated at least once. The repetitions convey Devadatta’s obsession with Yasodhara (‘I want to say my prayers / and mantras, but I smell her hair, her scent of jasmine’). We also hear of his struggles with bodily aches (often the bane of the meditator). Devadatta says, ‘I find it hard to have / self-discipline’ and ‘I find it hard / to gain self-discipline’ [Emphasis mine]. It’s as if self-discipline might be ‘had’ like a coveted other, or bought, or hoarded like wealth; he doesn’t say he finds discipline hard to develop or cultivate.

Beveridge’s poetry, though, is aligned with an avowed practice of cultivation. She pursues a hard-won poetry of the ‘finished article’, of the ‘exact phrase’. But such a poetry, when paired with formal niceties, arguably sits a little awkwardly with the disposition and voice of Beveridge’s Devadatta. But perhaps his poetry can be seen as a cathartic outlet, with the formal, ordering processes undertaken therein constituting a mode of sublimation. On the other hand, Devadatta doesn’t seem to embody the kind of discipline needed to produce a ‘hard-won’ poem, and he is certainly not ‘the finished article’. But he doesn’t feel the Buddha fits the latter description either—and this scepticism regarding the Buddha’s attainment, teachings and methods makes for some pointed, scathing or even scandalous poems where much of the collection’s drama emerges.

In ‘The Buddha at Uruvela’ (p. 26) the Buddha is addressing a crowd, and Devadatta wonders to himself: ‘Can’t they see Buddha speaks from the privilege / of a high-borne, well heeled past?’. Devadatta continues: ‘Don’t these / / folk know what shackles them to suffering / is not desire, as the Buddha exposits, but the hard-set, / iron-fisted system of caste.’ Note the full stop after ‘caste’, where one might have expected a question mark. It’s as if Devadatta, being some kind of proto-Marxist, couldn’t bear to see a question mark following what he perhaps sees as a statement of fact.

It’s difficult to deny the importance of caste to the Buddha’s life; indeed, he can be seen as a radical of his time because he allowed members of any caste to join his order. He went against the ideological grain by pointing out that caste, in and of itself, was not an index of one’s spiritual birthright, or one’s potential for awakening. And while Devadatta is right to raise questions of caste and ideology, he seems to put the cart before the horse by nominating the caste system, rather than desire, as the ultimate source of suffering. For what is the caste system if not a programmatic structure to serve the desires of the few at the expense of the desires of the many? From a Buddhist perspective, it might be said that the caste system arises out of craving and aversion (i.e. the two sides of the coin of desire), as well as delusions associated with essentialistic separations between ‘self’ and ‘other’.

Beveridge eschews any claims Devadatta might have to saintliness, and makes no mention of his demand that monastics be more rigorously ascetic than required by the Buddha. As recounted in the Pāli Canon, this demand was, on one level, a ruse employed to create a schism; but it might also be seen as heartfelt. Beveridge has admitted that, compared to his canonical counterpart, her Devadatta is ‘much more lascivious and pleasure seeking’ (p. 3). He is marked as obsessive, covetous, bitter, vengeful, conniving. He’s a gambler, a drinker of wine and koumis, a smoker of hash. He craves delicious food, sexual pleasures, a carnival; if not luxury then certainly not the ‘poverty and slim pickings’ he ascribes to the monk’s lot (p. 15). He lets ‘desire have its ground’ (‘Vultures Peak’, p. 29). All of this flies in the face of the Buddha’s prescriptions for overcoming suffering and attaining enlightenment.

As a kind of nemesis or anti-Buddha figure, it seems appropriate that Devadatta’s cravings and attachments come to nothing. His scheming is ineffectual, and his attempts on the Buddha’s life are botched. In ‘Rocks, Vultures Peak’ (p. 52), Devadatta dislodges a sizeable rock from on high as the Buddha passes below; but the Buddha is ‘barely injured. A cut on his toe.’ Devadatta is at a distance; there is no direct confrontation as such—and this is true of all three methods he employs in attempting to kill the Buddha. Indeed, in forging his character and voice, Beveridge seems to have honed in on Devadatta’s remoteness. He does get on famously with his partner-in-scheming Ajatasattu, who seems just as grasping as him. But it’s noteworthy that all of Devadatta’s poems involving Yasodhara, and almost all involving Siddhattha are either recollections or (day)dreams. There is no ‘direct’, ‘present’ interaction or dialogue between these key characters. Perhaps if Beveridge had attempted to convey such interactions directly, it would have put too great a strain on the voice of the poems—or else some dramatic vehicle other than Devadatta’s voice may have been required?

It’s as if Devadatta has attained some kind of anti-nirvana of infinite, unfulfilled desires. He seems to be caught in past and future; he’s either stewing over past ‘injustices’, plotting Siddhattha’s downfall, or fantasising about Yasodhara. The ‘now’ only seems to get his attention when it involves sensual desire or disgust. And these are interwoven with imagination: cravings clawing towards an imagined future, aversions tending to draw upon the past (e.g. traumatic experiences).

I found Devadatta’s Poems a more grounded sequence than ‘Between the Palace and the Bodhi Tree’. Certainly Devadatta’s diction in the former is less elevated than Siddhattha’s in the latter. ‘Between …’ was dedicated to Dorothy Porter, but it is Devadatta’s Poems that calls to mind Akhanaten and the darker soundings of Porter’s verse novels. Devadatta’s Poems gains vitality from its strokes of humour and playfulness; its flights of sound and sensuality in describing Devadatta’s world; its narrative frictions; and its gritty exploration of the all-too-human.

Citations

Beveridge, Judith, Accidental Grace, Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1996.

Beveridge, Judith, Wolf Notes, Artarmon: Giramondo, 2003.

Bhikkhu Anālayo, ‘Oral Dimensions of Pāli Discourses: Pericopes, other Mnemonic Techniques and the Oral Performance Context’, Canadian Journal of Buddhist Studies, Number Three, 2007, Toronto: Nalanda College of Buddhist Studies.

Bhikkhu Sujato, ‘Why Devadatta Was No Saint’, Santipada, 24 Oct 2012, accessed 11 May 2016, <http://santifm.org/santipada/2010/why-devadatta-was-no-saint/>.

Ray, Reginald, Buddhist Saints in India: A Study in Buddhist Values and Orientations, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

STU HATTON is a poet, critic and editor based in Dja Dja Wurrung country. His work has appeared in The Age, Best Australian Poems 2012, Cordite, Overland and elsewhere. He has published two collections: How to be Hungry (2010) and Glitching (2014). Sometimes he posts things at http://outerblog.tumblr.com.

John Kinsella’s most recent books of poetry are Firebreaks (WW Norton, 2016) and Drowning in Wheat: Selected Poems (Picador, 2016). His most recent book of short stories is Crow’s Breath (Transit Lounge, 2015). He is a Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge University, a Professorial Research Fellow at UWA, and Professor of Literature and Sustainability at Curtin University.

John Kinsella’s most recent books of poetry are Firebreaks (WW Norton, 2016) and Drowning in Wheat: Selected Poems (Picador, 2016). His most recent book of short stories is Crow’s Breath (Transit Lounge, 2015). He is a Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge University, a Professorial Research Fellow at UWA, and Professor of Literature and Sustainability at Curtin University. Fresh News from the Arctic (Anne Elder Award), This Floating World (shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards and The Age Book of the Year Awards), and Wild (shortlisted for the New South Wales Premier’s Literary Awards).

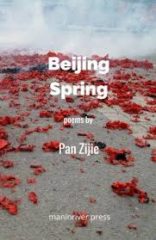

Fresh News from the Arctic (Anne Elder Award), This Floating World (shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards and The Age Book of the Year Awards), and Wild (shortlisted for the New South Wales Premier’s Literary Awards). Bejing Spring

Bejing Spring Teya Brooks Pribac is a vegan and animal advocate, working between Australia and Europe. She engages in various verbal and visual art forms as a hobbyist. She’s currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Sydney researching animal grief. She lives in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales with other animals.

Teya Brooks Pribac is a vegan and animal advocate, working between Australia and Europe. She engages in various verbal and visual art forms as a hobbyist. She’s currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Sydney researching animal grief. She lives in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales with other animals. William Russell, born in Victoria, has been published in journals and anthologies in Australia and overseas, including: This Australia; Meanjin; Borderlands; Antipodes;and Paintbrush—and Inside Black Australia; Spirit Song; and The Sting in the Wattle. Poems like Red, God Gave Us Trees To Cut Down, Blackberrying and Tali Karng: Twilight Snake have been included in international anthologies and education curricula. Peer poet-playwright Gerry Bostock spoke of him as someone really up against the odds: “a blind, ex-serviceman of the Vietnam era, with PTSD, a fair-skinned Aboriginal male—and, worst of all, a poet.” William draws from defining and extraordinary life experience, disability and deep cultural roots to create a diverse repertoire of poetry.

William Russell, born in Victoria, has been published in journals and anthologies in Australia and overseas, including: This Australia; Meanjin; Borderlands; Antipodes;and Paintbrush—and Inside Black Australia; Spirit Song; and The Sting in the Wattle. Poems like Red, God Gave Us Trees To Cut Down, Blackberrying and Tali Karng: Twilight Snake have been included in international anthologies and education curricula. Peer poet-playwright Gerry Bostock spoke of him as someone really up against the odds: “a blind, ex-serviceman of the Vietnam era, with PTSD, a fair-skinned Aboriginal male—and, worst of all, a poet.” William draws from defining and extraordinary life experience, disability and deep cultural roots to create a diverse repertoire of poetry. My name is Tan Duc Thanh Nguyen. Writing found me at a time I needed it most. It has helped me to heal and has shown me a world I didn’t know existed.

My name is Tan Duc Thanh Nguyen. Writing found me at a time I needed it most. It has helped me to heal and has shown me a world I didn’t know existed.