Ravi Shankar reviews Empty Chairs by Liu Xia

Empty Chairs

Empty Chairs

by Liu Xia. Translated from the Chinese by Ming Di and Jennifer Stern; Introduction by Liao Yiwu; Foreword by Herta Müller

ISBN 978-1-5559772-5-2

Reviewed by RAVI SHANKAR

On April 1st, 2018—that rare conjunction of Easter Sunday with April Fool’s day in the West—Chinese painter, photographer and poet Liu Xia celebrated her 57th birthday as she has every single year since 2010: under house arrest. Better known as the wife of the late Liu Xiaobo, the dissident Chinese academic who was jailed for the last years of his life after co-authoring Charter 08 (that seminal manifesto meant to emulate Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77 by making a public case for basic civil rights, democracy, and freedom in China, and written on the approach of the 20th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre of pro-democracy student protesters, of which he had once been one), Liu Xia is a formidable and too-little-known literary figure in her own right. All of that changes with the publication of Empty Chairs (Graywolf, 2015), a bilingual translation of her selected poems, translated muscularly from the Chinese by Ming Di and Jennifer Stern and with a foreword by German Nobel Prize Laureate, Herta Müller.

As a poet and activist, Liu Xia is someone whose courageous work in the face of overt repression makes her a kind of 21st century Anna Akhmatova. When her husband, sentenced to 11 years in jail for incitement to subvert state power, won the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize for “long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China,” he was barred from attending the awards ceremony and instead was represented on stage by an empty chair. Thorbjoern Jagland, chairman of the Nobel committee, placed that year’s medal and citation on a vacant blue upholstered seat, which then became such a powerful metaphor for the fight against despotism and suppression of freedom everywhere, that Chinese internet censors forbade the posting of photos or even drawings of empty chairs on its social media platforms. But there was never just one empty chair.

As Shayna Bauchner writes for Human Rights Watch, “in her remarks for a 2009 award ceremony honoring her husband, Liu Xia wrote, “I am not a vassal of Liu Xiaobo.” Yes, she has played an inextricable role in the chronicle of her husband’s imprisonment and his global prominence as a face of Chinese dissidence. She has been his artistic collaborator, one of his few visitors in prison, and, with his death, the bearer of his legacy. But no one should lose sight of her singular status as a fiercely independent advocate, an elegiac storyteller, and an enduring survivor of the seven-year isolation imposed on her by the Chinese government. Liu Xia has been held in unlawful house arrest since October 2010 “…detained without charge or trial, she has been stripped of communication with the outside world and denied adequate medical care.” Or as Ye Du, a writer and longstanding friend attested to more succinctly in an interview for The Guardian, “Liu Xia has been physically and mentally destroyed.”

So while her plight has become something of a cause célèbre among writers and intellectuals (recently in November 2017, over 50 international authors, including Chimamanda Adichie, Philip Roth, Margaret Atwood, Tom Stoppard, Louise Erdrich, Stephen Sondheim and George Saunders wrote a letter to Chinese president Xi Jinping appealing to his sense of conscience and compassion to release Liu Xia; unsurprisingly the letter went unanswered and unheeded), her poetry has not been widely read — nor indeed has it been widely available — in the English-speaking world. In part, this might be due to her growing reputation as a visual artist, a sensibility that helps illuminate the stark shape of her poems; but doubtlessly, in large part, it’s also due to the simple fact that she’s a woman. Earlier in her life, she was eclipsed in her marriage by Liu Xiaobo’s fame and persecution; then later in life, she was overtly censored by the State just for having chosen to be with him, even though she insists she is apolitical. In neither case was she given a choice; or a voice.

An early poem “June 2nd, 1989” attests to the nature of her relationship to her husband, who had just been jailed for the first time after the protests at Tiananmen Square. Dedicated to Xiaobo, the poem reads:

This isn’t good weather

I said to myself

standing under the lush sun.

Standing beside you

I patted your head

and your head pricked my palm

making it strange to me.

I didn’t have a chance

to say a word before you became a character

in the news, everyone looking up to you

as I was worn down

at the edge of a crowd.

just smoking

and watching the sky.

A new myth, maybe, was forming there,

but the sun’s sharp light

blinded me from seeing it.

If one of the techniques of the Chinese Misty Poets was the deployment of hermetic, obscurantist imagery as a response against the Maoist aesthetic of social realism, then one of the remarkable things about Liu Xia’s work is how she manages to reconnect with plain-spoken, vernacular language without losing any of the philosophical complexity or subversive power of her male counterparts. Ezra Pound that early exponent and translator (although, ‘transliterator’ or ‘re-creator’ might be the more apt designation, considering that Pound not only didn’t know the source language, but that his understanding of its very structure was misinformed by Ernest Fenollosa’s unpublished scholarly papers, which formed the basis of his 1915 collection, Cathay) defined an image as “an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time” and it’s hard to conjure a better example than in that first stanza.

First, we are struck by the speaker’s interiority; though this is a poem dedicated to a beloved, the poem opens with an internal conversation (“I said to myself”). Next, we realize the oddity of the perspective; someone standing under a lush sun yet nonetheless laments the weather? There’s both emotion and intellect here and the image resonates on both the literal and the figurative plane, especially when we read the next stanza, which introduces the beloved “you”. Unlike the sun, which the speaker stands under, she stands beside her beloved, a telling detail that gets at their love and mutuality. Yet the speaker still doesn’t like the weather from where she stands; she pats her husband’s head in that time-honored conciliatory gesture (far be it for him to comfort her) and feels pricked in return by his head, which suddenly feels foreign.

Ostranenie is the theory of estrangement or de-familiarization developed by the Russian literary theorist Victor Shklovsky. A neologism, it implies both the action of pushing aside and that of making strange; for art, the theory goes, to reach its maximal empathic level, it needs to shift the borders of ordinary perception until the quotidian becomes queer again. Liu Xia’s poem embodies this concept, for the speaker’s beloved’s head, that intimate, well-known corporeal organ, suddenly transforms itself into something that pricks the palm. The subsequent stanza further deepens the connotation of this alienation through a masterful metamorphosis.

I don’t read Mandarin, but I can only trust Ming Di and Jennifer Stern when they write in their translator’s note that they talked “through a way to remain true to impossibly collapsed dichotomies, to a person who we feel like we know but don’t. We have tried to remain true to what we value in the work, to what’s rooted in the gutted and stark political present in China, and in the loving, friendly, funny, insightful and engaged voice.” This book reaps the fruits of that dialogue and to that list of adjectives, I’d also add “dry” and “devastating” for her use of biting understatement. “I didn’t have a chance / to say a word before you became a character / in the news, everyone looking up to you / as I was worn down / at the edge of a crowd / just smoking / and watching the sky.”

This is an Ovidian transformation, for the beloved, whose head the speaker was just rubbing, has suddenly become, through exposure to public consciousness, a character (in all senses of that word), which moves him into proximity with the lush sun and far from her, worn down and receding in the face of the anonymous masses. It’s doubly heart-breaking in that though she’s the one who suffers, she’s nonetheless also the one who has to console him (and in time will have to care-take his memory). The last stanza, alludes to this possibility in brilliantly tying the poem together: “A new myth, maybe, was forming there, / but the sun’s sharp light / blinded me from seeing it.”

I love this provisional quality of Liu Xia’s work. The “maybe” in that moment is like the uncertainties in Marianne Moore. Her soulmate was turning into both newsprint and martyr before her very eyes, and his life (and her own life, though she might not have fully realized it then) had stopped belonging to him. It had become an instrument of the state or a tool for counter-propaganda, but that warm head she has cradled so many nights was changing into something else and she was powerless to stop it. That’s the fundamental heartbreak that infuses so many of these poems, and even though they are starkly quiet verbal artifacts, they nonetheless radiate such volumes of anguish and mortal heat.

Nearly ten years later, Liu Xiaobo was detained for writing an open letter advocating for human rights and then sentenced in 1996 to three more years in prison. During this time, Liu Xia would make routine camp visits, famously announcing to the guards that she wanted “to marry that enemy of the state!” Eventually they did get married, while Liu Xiaobo was still imprisoned, and held their banquet in the prison canteen. Their love story is truly one of the great love stories of our time.

It was during this time that Liu Xia composed some of the poems that constitute the middle section of Empty Chairs and one in particular, “Nobody Sees Me,” expresses an austere existentialism. The poem begins, “Nobody sees me / helpless. / I’m not being cursed. I’m just easily / attracted to unattainable things — / things that reject me, / that are outside what’s real.” The baldness of that declaration, without blame, lacking remorse, is astonishing. It’s a matter-of-fact embrace of the human condition that even Beckett might have admired. The poem continues:

My life steals from me.

I believe in a life that is an absurd

fantasy and is also hyperreal,

a life that hides behind death masks

and looming shadows.

…

I see a shadow walking on death’s path–

slowly, rhythmically,

calmly. Nobody

speaks a word.

I wave–nobody

sees me.

My life steals from me. Just for that line, readers should be jostling for Liu Xia’s insight. Often in her work, she will bifurcate herself, disassociating mind from body, or spirit from stasis, and she does so again here, seeing in herself “a shadow walking on death’s path.” Her greeting, like her predicament, falls on blind eyes, as the world has turned her into a perpetual Persephone, doomed to be a shade in the underworld. It’s telling, therefore, that the other writers and artists she calls out to and finds kinship with in this book were equally misunderstood and driven to madness in their own time: Van Gogh, Kafka, Nijinsky and Marguerite Duras. “The words emerge from her body without her realizing it,” Marguerite Duras wrote in Summer Rain and she could have been describing Liu Xia, “as if she were being visited by the memory of a language long forsaken.”

Indeed, in Empty Chairs, certain tropes and images recur obsessively throughout the book. Cigarettes, dolls and birds populate poem after poem. As the late American poet Richard Hugo advises us in his book Triggering Town, “don’t be afraid to take emotional possession of words,” and Liu Xia takes that advice, which it’s unlikely she ever heard, straight to heart. Seemingly banal, when these motifs recur, something extraordinary starts to happen; the objects begin to take on a powerful symbolic weight that transcends their literal shape in the world. The dolls and cigarettes become totemic while the poems themselves grow more airless and claustrophobic, qualities that evoke the very conditions of living under house arrest. It’s amazing that these images so insistently thread through 30 years of her poetry.

The dolls tie back to Liu Xia’s photography of what she called “ugly babies.” During a period of domestic confinement with her husband, Liu Xia took hundreds of photos of expressive, disfigured dolls that have become representative of the suffering faced by the Chinese people in general. Discovered by French writer Guy Sorman when he was visiting Liu Xia in Beijing, the photographs, captured on a tiny Russian camera and developed by turning her kitchen into a darkroom, toured the world in an exhibit called “The Silent Strength of Liu Xia” (taken from the title of one of her poems). It was an exhibition that Liu Xia would never know about, as her contact with the outside world has been effectively cut off.

As Sorman writes about these extraordinary photos, “Nearly all of the photos are taken with this old camera, without lights, in their apartment. And she’s able to build all these dramatic stories and metaphors with [such] limited technical resources. I think it is this contradiction which makes the photos really impressive.” Although Sorman is discussing her photography here, he might as well be analyzing her poems, for the same principles hold true in both cases. I don’t know if Liu Xia has limited technical resources in poetry (I would seriously doubt it, given how well-crafted her work seems to be in translation), but I do know that she intentionally chooses a simplified vocabulary, without any of the lavish opacity or numinous lyricism of her contemporaries, like Xi Chuan or Ouyang Jianghe (whose own selected poems, Notes on the Mosquito and Doubled Shadows respectively, the first translated by Lucas Klein and the second by Austin Woerner, are both well worth reading). In a certain way, her spare, harrowing poems resemble Paul Celan’s love affair with silence, in that the less they say, the more substantial the unsaid becomes. This ultimately is Liu Xia’s masterstroke; condemned by the Chinese state to silence, she uses her silence against them.

The final poem in the collection “How it Stands” crystallizes this stance, practiced over the years into a way of being. In it, as in earlier poems, the speaker is split in half and like the metaphysical poets of the 17th century did, she engages in a dialogue with herself.

Is it a tree?

It’s me, alone.

Is it a winter tree?

It’s always like this, all year round.

…

Aren’t you tired of being a tree your whole life?

Even when exhausted, I want to stand.

The Surrealist anthropomorphism is tempered by Buddhist reconciliation in these lines; and the poem is just heart-breaking. Leafless, bird-less, rooted in one spot, the poet provides a vision of a life that no human being should endure. It’s the kind of human rights abuse that trumps any technological or economic progress a country might make. In this final poem in Liu Xia’s Empty Chairs, the barren tree becomes yet another empty chair, another reminder of all of those people around the world without basic freedoms and civil liberties, even when their only crime might be using language or making art. Though the Chinese government would rather crush her and erase her husband’s memories, this vital collection of poems is an indication of the resilience of our human spirit, which cannot be silenced. There’s great sorrow in her work, but also remarkable strength, and with Graywolf’s publication of Empty Chairs, we are given renewed hope that her and her husband’s love story and alarming martyrdom will never be forgotten.

RAVI SHANKAR is author/editor of a dozen books, including most recently The Golden Shovel: New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks and Autobiography of a Goddess, translations of the 9th century Tamil poet/saint, Andal, and winner of the Muse India Translation Prize. He founded the online journal of arts Drunken Boat, has won a Pushcart Prize and a RISCA artist grant, has appeared in The New York Times, The Paris Review, on NPR, the BBC and PBS, received fellowships from the Corporation of Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony and been interviewed and translated into over 10 languages. His The Many Uses of Mint: New and Selected Poems 1997-2017 will be out in Australia with Recent Works Press in 2018.

The Stolen Bicycle

The Stolen Bicycle Lunar Inheritance

Lunar Inheritance NICHOLAS JOSE has published seven novels, including Paper Nautilus (1987), The Red Thread (2000) and Original Face (2005), three collections of short stories, Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (a memoir), and essays, mostly on Australian and Asian culture. He was Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy Beijing, 1987-90 and Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, 2009-10. He is Professor of English and Creative Writing at The University of Adelaide, where he is a member of the J M Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice.

NICHOLAS JOSE has published seven novels, including Paper Nautilus (1987), The Red Thread (2000) and Original Face (2005), three collections of short stories, Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (a memoir), and essays, mostly on Australian and Asian culture. He was Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy Beijing, 1987-90 and Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, 2009-10. He is Professor of English and Creative Writing at The University of Adelaide, where he is a member of the J M Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice. Middle of the Night

Middle of the Night Xia Fang, born in 1986, is a bilingual poet and translator. She has published two collections of translated poems and her own poetry has appeared in

Xia Fang, born in 1986, is a bilingual poet and translator. She has published two collections of translated poems and her own poetry has appeared in  Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu

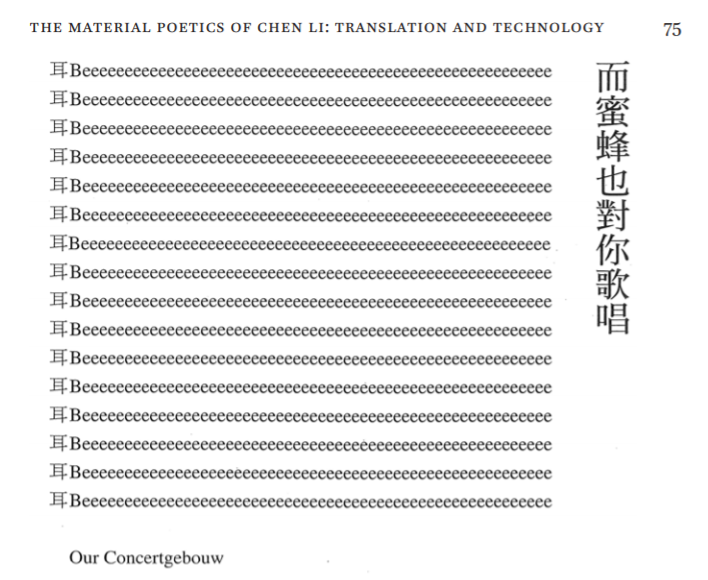

Genre of The Poison of Polygamy by Qiuping Lu Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Xiaoshuai Gou was born and raised in China. He has been working as a teacher of English and Mandarin as a second language and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of South Australia.

Xiaoshuai Gou was born and raised in China. He has been working as a teacher of English and Mandarin as a second language and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts at the University of South Australia. Sanaz Fotouhi is currently the director of Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. Born in Iran, she grew up across Asia and holds a PhD in English literature from the University of New South Wales. Her book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution was published in 2015 (I.B. Tauris). Her stories and creative fiction are a reflective of her multicultural background. Her work has appeared in anthologies in Australia and Hong Kong, including Southerly, The Griffith Review, as well as in the Guardian UK and the Jakarta Post. Sanaz is one of the founding members of the Persian Film Festival in Australia as well as the co-producer of the multi-award winning documentary film, Love Marriage in Kabul.

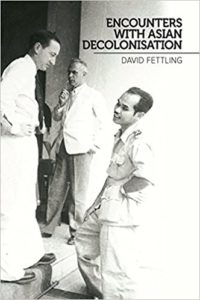

Sanaz Fotouhi is currently the director of Asia Pacific Writers and Translators. Born in Iran, she grew up across Asia and holds a PhD in English literature from the University of New South Wales. Her book The Literature of the Iranian Diaspora: Meaning and Identity since the Islamic Revolution was published in 2015 (I.B. Tauris). Her stories and creative fiction are a reflective of her multicultural background. Her work has appeared in anthologies in Australia and Hong Kong, including Southerly, The Griffith Review, as well as in the Guardian UK and the Jakarta Post. Sanaz is one of the founding members of the Persian Film Festival in Australia as well as the co-producer of the multi-award winning documentary film, Love Marriage in Kabul. Encounters with Asian Decolonisation

Encounters with Asian Decolonisation Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a Chinese statesman, writer and philosopher of the Song dynasty. A significant portion of his career was spent working on China’s defences along the North-western border, which inspired the theme of loneliness in his writings. His best-known poems contrasted his experience of solitude and homesickness with a sense of duty to his country and people.

Fan Zhongyan (989-1052) was a Chinese statesman, writer and philosopher of the Song dynasty. A significant portion of his career was spent working on China’s defences along the North-western border, which inspired the theme of loneliness in his writings. His best-known poems contrasted his experience of solitude and homesickness with a sense of duty to his country and people. Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) lived during the Song dynasty and was considered one of the most accomplished woman poets in Chinese history. Many of her poems intimately reflect her experiences of love, loss, fear and uncertainty living in a war-torn China.

Li Qingzhao (1084-1151) lived during the Song dynasty and was considered one of the most accomplished woman poets in Chinese history. Many of her poems intimately reflect her experiences of love, loss, fear and uncertainty living in a war-torn China. Yunhe Huang is a Chinese writer based in Australia. She has written poetry and prose in both Chinese and English, using a variety of genres from Song-dynasty

Yunhe Huang is a Chinese writer based in Australia. She has written poetry and prose in both Chinese and English, using a variety of genres from Song-dynasty  Wanling Liu (born 1989, China) completed her MA in Translation and Transcultural Communication at the University of Adelaide. She is a literary translator and teaches translating and interpreting in Adelaide. She has developed a passion for performance poetry and storytelling events and has won spoken word prizes with her poetry published in local anthologies.

Wanling Liu (born 1989, China) completed her MA in Translation and Transcultural Communication at the University of Adelaide. She is a literary translator and teaches translating and interpreting in Adelaide. She has developed a passion for performance poetry and storytelling events and has won spoken word prizes with her poetry published in local anthologies.

Martin Kovan is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which in recent years has been published in major Australian literary journals, as well as in France, the U.K., U.S.A., India, Hong Kong, Thailand and the Czech Republic. He completed graduate English studies with the U.S. poet, Gary Snyder, at UC Davis. He is completing a PhD in academic ethics and philosophy, and has volunteered in humanitarian work in South East Asia.

Martin Kovan is an Australian writer of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, which in recent years has been published in major Australian literary journals, as well as in France, the U.K., U.S.A., India, Hong Kong, Thailand and the Czech Republic. He completed graduate English studies with the U.S. poet, Gary Snyder, at UC Davis. He is completing a PhD in academic ethics and philosophy, and has volunteered in humanitarian work in South East Asia. HC Hsu is author of the short story collection Love Is Sweeter (Lethe) and essay collection Middle of the Night (Deerbrook), which has been nominated for the Housatonic Award, CALA Award and Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature. Memoir competition winner and The Best American Essays nominee, he has written for Pif, Big Bridge, Iodine, nthposition, 100 Word Story, China Daily News, Epoch Times, Words Without Borders, and many others. He has served as interpreter for the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China, and his translation of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo’s biography Steel Gate to Freedom was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2015.

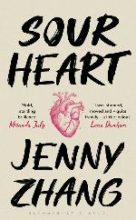

HC Hsu is author of the short story collection Love Is Sweeter (Lethe) and essay collection Middle of the Night (Deerbrook), which has been nominated for the Housatonic Award, CALA Award and Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature. Memoir competition winner and The Best American Essays nominee, he has written for Pif, Big Bridge, Iodine, nthposition, 100 Word Story, China Daily News, Epoch Times, Words Without Borders, and many others. He has served as interpreter for the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China, and his translation of 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo’s biography Steel Gate to Freedom was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2015. Sour Heart

Sour Heart

Carielyn Tunion aka ALIENCRY is a multidisciplinary artist & serial story peddler with experience in visual arts, illustration, screen production & creative content production. Her focus is on community empowerment through representation, decolonisation practice, and creative collaboration. Her work has appeared in The Experience Magazine, ISMS-zine, Vertigo, 2TheFront Zine. She has exhibited at Lowbrow Denver Pintastic Exhibition, Colorado, Amber Rose’s Slutwalk, LA. This video was part of the SAD N ASIAN group show in New York, and at a @kaleidopress event in 2017.

Carielyn Tunion aka ALIENCRY is a multidisciplinary artist & serial story peddler with experience in visual arts, illustration, screen production & creative content production. Her focus is on community empowerment through representation, decolonisation practice, and creative collaboration. Her work has appeared in The Experience Magazine, ISMS-zine, Vertigo, 2TheFront Zine. She has exhibited at Lowbrow Denver Pintastic Exhibition, Colorado, Amber Rose’s Slutwalk, LA. This video was part of the SAD N ASIAN group show in New York, and at a @kaleidopress event in 2017. Ella Jeffery’s poetry, reviews and essays have appeared in Meanjin, Westerly, Cordite,

Ella Jeffery’s poetry, reviews and essays have appeared in Meanjin, Westerly, Cordite, Michelle Cahill’s short story collection Letter to Pessoa won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing.The Herring Lass is her most recent poetry collection. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland Review, Meanjin, Island, Antipodes, Best Australian Poems and the Forward Book of Poetry, 2018. She co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets with Adam Aitken and Kim Cheng Boey, and Vagabond’s deciBels3 with Dimitra Harvey. With Professor Wenche Ommundsen she was a University of Wollongong conference delegate at Wuhan University’s 2017 ‘China: One Belt, One Road.’

Michelle Cahill’s short story collection Letter to Pessoa won the NSW Premier’s Literary Award for New Writing.The Herring Lass is her most recent poetry collection. Her poems have appeared in Poetry Ireland Review, Meanjin, Island, Antipodes, Best Australian Poems and the Forward Book of Poetry, 2018. She co-edited Contemporary Asian Australian Poets with Adam Aitken and Kim Cheng Boey, and Vagabond’s deciBels3 with Dimitra Harvey. With Professor Wenche Ommundsen she was a University of Wollongong conference delegate at Wuhan University’s 2017 ‘China: One Belt, One Road.’ Billy Sing

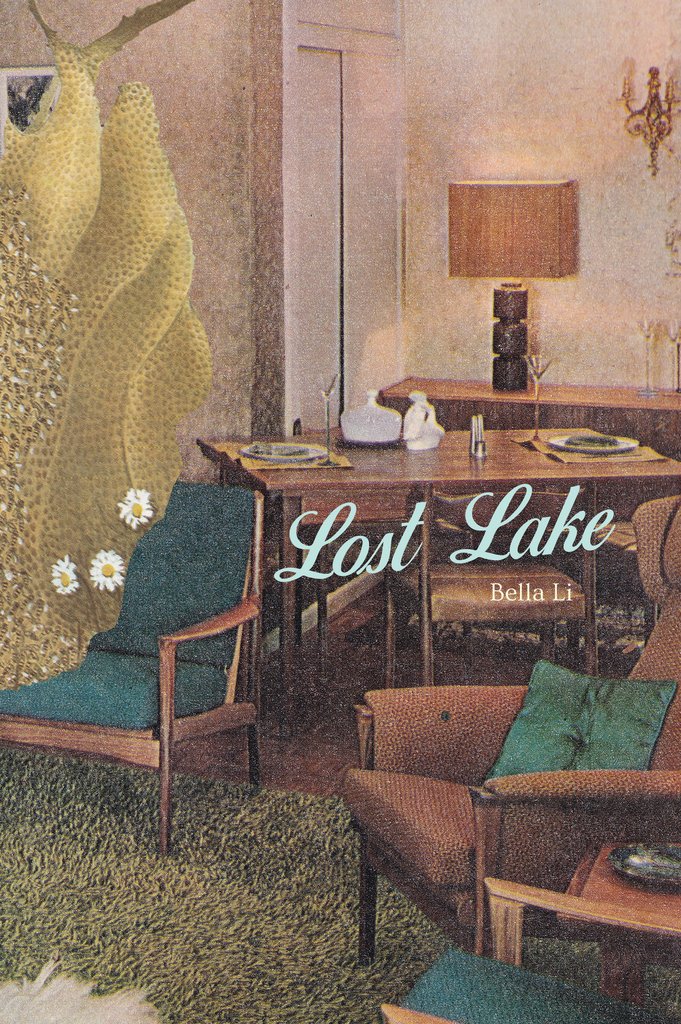

Billy Sing Argosy and Lost Lake

Argosy and Lost Lake

May Ngo is a researcher in the social sciences, focusing on development in Cambodia. Her other interests include theology, migration, diaspora and literature. She is also developing her father’s memoirs of his time with the Vietnamese communist army as a novel. She has a blog at The Violent Bear it Away (https://theviolentbearitaway1.wordpress.com/) and tweets at @mayngo2

May Ngo is a researcher in the social sciences, focusing on development in Cambodia. Her other interests include theology, migration, diaspora and literature. She is also developing her father’s memoirs of his time with the Vietnamese communist army as a novel. She has a blog at The Violent Bear it Away (https://theviolentbearitaway1.wordpress.com/) and tweets at @mayngo2 Lynda Ng was born in Wollongong. She is a graduate of the NIDA Playwrights Studio and the editor of

Lynda Ng was born in Wollongong. She is a graduate of the NIDA Playwrights Studio and the editor of  Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection, Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor,] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Luo Lingyuan was born in 1963 and is a German-Chinese writer. After studying Journalism and Computer Science in Shanghai, she has lived in Berlin since 1990 and published works in German and Chinese including four novels, two short story collections and numerous pieces in literary journals. In 2007 her short story collection, Du Fliegst für Meinen Sohn aus dem Fünften Stock [You Fly for My Son from the Fifth Floor,] received an Adelbert-von-Chamisso Advancement Award, a prize awarded to works written in German, dealing with ‘cultural change‘. In 2017 she was Writer in Residence in Erfurt.

Emily Yu Zong has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Queensland, where she remains an honorary research fellow. Her doctoral thesis on Asian Australian and Asian American women writers was awarded the 2016 UQ Dean’s Award for Outstanding Higher Degree by Research Theses. Her research interests include ethnic Asian literature, gender and sexuality, and literature and the environment. She has published academic articles, interviews, and book reviews in Journal of Intercultural Studies, JASAL, New Scholar, Mascara Literary Review, and Australian Women’s Book Review.

Emily Yu Zong has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Queensland, where she remains an honorary research fellow. Her doctoral thesis on Asian Australian and Asian American women writers was awarded the 2016 UQ Dean’s Award for Outstanding Higher Degree by Research Theses. Her research interests include ethnic Asian literature, gender and sexuality, and literature and the environment. She has published academic articles, interviews, and book reviews in Journal of Intercultural Studies, JASAL, New Scholar, Mascara Literary Review, and Australian Women’s Book Review. Janet Jiahui Wu is a visual artist and writer of fiction and poetry. She has published in Voiceworks Literary Magazine, Cordite Poetry Review and Rabbit Poetry Journal. She currently resides in Adelaide, South Australia.

Janet Jiahui Wu is a visual artist and writer of fiction and poetry. She has published in Voiceworks Literary Magazine, Cordite Poetry Review and Rabbit Poetry Journal. She currently resides in Adelaide, South Australia. A.J. Carruthers is an Australian-born experimental poet, literary critic and lecturer in the Australian Studies Centre at SUIBE in Shanghai. He is author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems, 1961-2011 (Palgrave 2017), a book of literary criticism that examines five North American long poems and their relation to musical structures and musical scores. The first volume of his epic poem, AXIS Book 1: Areal, was published in 2014 (Vagabond). Opus 16 on Tehching Hsieh is a downloadable eBook from

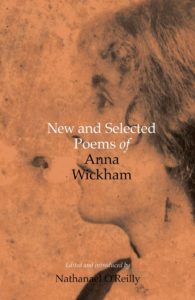

A.J. Carruthers is an Australian-born experimental poet, literary critic and lecturer in the Australian Studies Centre at SUIBE in Shanghai. He is author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems, 1961-2011 (Palgrave 2017), a book of literary criticism that examines five North American long poems and their relation to musical structures and musical scores. The first volume of his epic poem, AXIS Book 1: Areal, was published in 2014 (Vagabond). Opus 16 on Tehching Hsieh is a downloadable eBook from  New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham Hidden Words Hidden Worlds:

Hidden Words Hidden Worlds:

Winner:

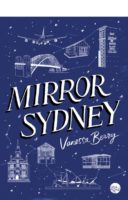

Winner:  Winner: Mirror Sydney by Vanessa Berry (Giramondo)

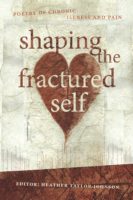

Winner: Mirror Sydney by Vanessa Berry (Giramondo) Winner: Shaping the Fractured Self Ed. Heather Taylor-Johnson (UWA Publishing)

Winner: Shaping the Fractured Self Ed. Heather Taylor-Johnson (UWA Publishing) The Lost Culavamsa: or the Unimportance of Being Earnest

The Lost Culavamsa: or the Unimportance of Being Earnest These Wild Houses

These Wild Houses Eunice Andrada is a Filipina poet, journalist, lyricist and teaching artist based in Sydney. Featured in the Guardian, CNN International, ABC News and other media, she has performed her poetry in diverse international stages, from the Sydney Opera House and the deserts of Alice Springs to the United Nations Climate Negotiations in Paris. During a residency in Canada’s prestigious Banff Centre, she collaborated with award-winning jazz musician and Cirque du Soleil vocalist Malika Tirolien. She has also shared her verses with celebrated composer Andrée Greenwell for the choral project Listen to Me. Eunice co-produced and curated Harana, a series of poetry tours led by Filipina-Australians in response to the Passion and Procession exhibition in the Art Gallery of NSW. Her poems have appeared in Peril, Verity La, Voiceworks, and Deep Water Literary Review, amongst other publications. She was awarded the John Marsden & Hachette Australia Poetry Prize in 2014. In 2018, the Amundsen-Scott Station in the South Pole of Antarctica will feature her poetry in a special exhibition on climate change. Flood Damages (Giramondo, 2018) is her first book of poetry.

Eunice Andrada is a Filipina poet, journalist, lyricist and teaching artist based in Sydney. Featured in the Guardian, CNN International, ABC News and other media, she has performed her poetry in diverse international stages, from the Sydney Opera House and the deserts of Alice Springs to the United Nations Climate Negotiations in Paris. During a residency in Canada’s prestigious Banff Centre, she collaborated with award-winning jazz musician and Cirque du Soleil vocalist Malika Tirolien. She has also shared her verses with celebrated composer Andrée Greenwell for the choral project Listen to Me. Eunice co-produced and curated Harana, a series of poetry tours led by Filipina-Australians in response to the Passion and Procession exhibition in the Art Gallery of NSW. Her poems have appeared in Peril, Verity La, Voiceworks, and Deep Water Literary Review, amongst other publications. She was awarded the John Marsden & Hachette Australia Poetry Prize in 2014. In 2018, the Amundsen-Scott Station in the South Pole of Antarctica will feature her poetry in a special exhibition on climate change. Flood Damages (Giramondo, 2018) is her first book of poetry. Elif Sezen, born in Melbourne in 1981, grew up both here and in Izmir, Western Turkey. She settled in Melbourne in 2007. Also an interdisciplinary visual artist, she writes original poetry in English and in Turkish. In 2014 she published her Turkish translation of Ilya Kaminsky’s acclaimed book Dancing in Odessa; her own first collection of experimental short stories in Turkish, Gece Düşüşü (‘Fall.Night.’), was published in 2012. Elif’s collection of poems Universal Mother was recently published by Gloria SMH Press, and she also published a chapbook The Dervish with Wings early 2017. She holds a PhD in Fine Arts from Monash University. www.elifsezen.com

Elif Sezen, born in Melbourne in 1981, grew up both here and in Izmir, Western Turkey. She settled in Melbourne in 2007. Also an interdisciplinary visual artist, she writes original poetry in English and in Turkish. In 2014 she published her Turkish translation of Ilya Kaminsky’s acclaimed book Dancing in Odessa; her own first collection of experimental short stories in Turkish, Gece Düşüşü (‘Fall.Night.’), was published in 2012. Elif’s collection of poems Universal Mother was recently published by Gloria SMH Press, and she also published a chapbook The Dervish with Wings early 2017. She holds a PhD in Fine Arts from Monash University. www.elifsezen.com Roisin Kelly is an Irish writer who was born in Belfast and raised in Leitrim. After a year as a handweaver on a remote island in Mayo and a Masters in Writing at National University of Ireland, Galway, she now calls Cork City home. Her chapbook Rapture (Southword Editions in 2016) was reviewed by The Irish Times as ‘fresh, sensuous and direct,’ while Poetry Ireland Review described her as ‘unafraid of sentiment…a master of endings.’ Publications in which her poetry has appeared include POETRY, The Stinging Fly, Lighthouse, and Winter Papers Volume 3 (ed. Kevin Barry and Olivia Goldsmith). In 2017 she won the Fish Poetry Prize. www.roisinkelly.com

Roisin Kelly is an Irish writer who was born in Belfast and raised in Leitrim. After a year as a handweaver on a remote island in Mayo and a Masters in Writing at National University of Ireland, Galway, she now calls Cork City home. Her chapbook Rapture (Southword Editions in 2016) was reviewed by The Irish Times as ‘fresh, sensuous and direct,’ while Poetry Ireland Review described her as ‘unafraid of sentiment…a master of endings.’ Publications in which her poetry has appeared include POETRY, The Stinging Fly, Lighthouse, and Winter Papers Volume 3 (ed. Kevin Barry and Olivia Goldsmith). In 2017 she won the Fish Poetry Prize. www.roisinkelly.com Heather Taylor Johnson’s recent publications are Meanwhile, the Oak (

Heather Taylor Johnson’s recent publications are Meanwhile, the Oak ( Can You Tolerate This

Can You Tolerate This

Cecily Niumeitolu is a PhD candidate researching Beckett’s archives at present. She has had three excursions in Philament, her writing has appeared in Voiceworks, Eclectica, Australian Reader, and she received the Henry Lawson Prize for Prose.

Cecily Niumeitolu is a PhD candidate researching Beckett’s archives at present. She has had three excursions in Philament, her writing has appeared in Voiceworks, Eclectica, Australian Reader, and she received the Henry Lawson Prize for Prose. Cameron Morse taught and studied in China. Diagnosed with Glioblastoma in 2014, he is currently a third-year MFA candidate at the University of Missouri—Kansas City and lives with his wife Lili and newborn son Theodore in Blue Springs, Missouri. His poems have been or will be published in New Letters, Bridge Eight, South Dakota Review, I-70 Review and TYPO. His first collection, Fall Risk, is forthcoming in 2018 from Glass Lyre Press.

Cameron Morse taught and studied in China. Diagnosed with Glioblastoma in 2014, he is currently a third-year MFA candidate at the University of Missouri—Kansas City and lives with his wife Lili and newborn son Theodore in Blue Springs, Missouri. His poems have been or will be published in New Letters, Bridge Eight, South Dakota Review, I-70 Review and TYPO. His first collection, Fall Risk, is forthcoming in 2018 from Glass Lyre Press. Rebecca Vedavathy is a research scholar studying Francophone Literature in EFLU, Hyderabad. She began writing as a child but only discovered its appreciation when she read a Francophone Literature class many years later. She won the Prakriti Poetry Contest, 2016. She longlisted in English Poetry for the Toto Funds the Arts Awards, 2017 and 2018. She is currently a Shastri Indo-Canadian Research Fellow interning at the University of Quebec, Montreal.

Rebecca Vedavathy is a research scholar studying Francophone Literature in EFLU, Hyderabad. She began writing as a child but only discovered its appreciation when she read a Francophone Literature class many years later. She won the Prakriti Poetry Contest, 2016. She longlisted in English Poetry for the Toto Funds the Arts Awards, 2017 and 2018. She is currently a Shastri Indo-Canadian Research Fellow interning at the University of Quebec, Montreal. Luke Best is from Toowoomba on the Darling Downs where he was born in 1982. He is married with three children. He has been published in Overland and his manuscript Percussion was Highly Commended in the 2017 Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize.

Luke Best is from Toowoomba on the Darling Downs where he was born in 1982. He is married with three children. He has been published in Overland and his manuscript Percussion was Highly Commended in the 2017 Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize. Rose Lucas is a Melbourne poet. Her first collection, Even in the Dark (University of WA Publishing), won the Mary Gilmore Award in 2014; her second collection was Unexpected Clearing (UWAP, 2016). She is currently working on her next collection At the Point of Seeing. She is a Senior Lecturer in the Graduate Research Centre at Victoria University.

Rose Lucas is a Melbourne poet. Her first collection, Even in the Dark (University of WA Publishing), won the Mary Gilmore Award in 2014; her second collection was Unexpected Clearing (UWAP, 2016). She is currently working on her next collection At the Point of Seeing. She is a Senior Lecturer in the Graduate Research Centre at Victoria University. Rafeif Ismail’s current work aims to explore the themes of home, belonging and Australian identity in the 21st century. A third culture youth of the Sudanese diaspora, her goal is to create works that

Rafeif Ismail’s current work aims to explore the themes of home, belonging and Australian identity in the 21st century. A third culture youth of the Sudanese diaspora, her goal is to create works that  Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria

Blindness and Rage: A Phantasmagoria Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark

Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark Susan Hurley is a health economist and writer. Her research has been published in numerous international journals including The Lancet and her articles and essays have appeared in Kill Your Darlings,The Big Issue, The Australian and Great Walks. Susan is currently working on a novel that originates from a disastrous drug trial. She lives in Melbourne with her husband and labradoodle. The Death of an Impala was shortlisted for the 2017 Peter Carey Short Story Prize.

Susan Hurley is a health economist and writer. Her research has been published in numerous international journals including The Lancet and her articles and essays have appeared in Kill Your Darlings,The Big Issue, The Australian and Great Walks. Susan is currently working on a novel that originates from a disastrous drug trial. She lives in Melbourne with her husband and labradoodle. The Death of an Impala was shortlisted for the 2017 Peter Carey Short Story Prize. Maris Depers is a Psychologist from Wollongong, NSW. His poetry and short stories have appeared in Kindling III and One Page Literary Magazine.

Maris Depers is a Psychologist from Wollongong, NSW. His poetry and short stories have appeared in Kindling III and One Page Literary Magazine. The Circle and the Equator

The Circle and the Equator Kathy Sharpe is a graduate of the University of Wollongong’s Master of Arts in Creative Writing. She

Kathy Sharpe is a graduate of the University of Wollongong’s Master of Arts in Creative Writing. She Georgia Manuela Delgado is a writer currently based in Sydney with a Portuguese mother. She recently graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from The University of Sydney.

Georgia Manuela Delgado is a writer currently based in Sydney with a Portuguese mother. She recently graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from The University of Sydney. Sentences from the Archive

Sentences from the Archive Sivashneel Sanjappa is a writer, chef and keen gardener originally from Fiji and currently based in Melbourne. He is currently working on his first novel. His work has been published previously in

Sivashneel Sanjappa is a writer, chef and keen gardener originally from Fiji and currently based in Melbourne. He is currently working on his first novel. His work has been published previously in  Jessie Tu’s poems and scripts have appeared in the Australian Book Review, FishFood Magazine and The Voices Project. Winner of 2016 Joseph Furphy Literary Prize in Poetry, she was shortlisted for the Peter Porter Poetry Prize in 2017. She is recently returned from a workshop in creative non-fiction writing at the Iowa Summer Writer’s Festival, University of Iowa. ‘Another Country’, an extract from her memoir-in-progress was shortlisted for the Deborah Cass Prize in 2017, judged by Alice Pung. Her poetry chapbook, You should have told me we have nothing left is forthcoming with Vagabond deciBels 3.

Jessie Tu’s poems and scripts have appeared in the Australian Book Review, FishFood Magazine and The Voices Project. Winner of 2016 Joseph Furphy Literary Prize in Poetry, she was shortlisted for the Peter Porter Poetry Prize in 2017. She is recently returned from a workshop in creative non-fiction writing at the Iowa Summer Writer’s Festival, University of Iowa. ‘Another Country’, an extract from her memoir-in-progress was shortlisted for the Deborah Cass Prize in 2017, judged by Alice Pung. Her poetry chapbook, You should have told me we have nothing left is forthcoming with Vagabond deciBels 3. A Personal History of Vision

A Personal History of Vision False Nostalgia

False Nostalgia Knocks

Knocks Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórquez & Alí Calderón

Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórquez & Alí Calderón Claire Potter ’s most recent poetry publications have appeared in The Fremantle Press Anthology of Western Australian Poetry (edited by John Kinsella and Tracy Ryan), Best Australian Poems 2016 (ed. Sarah Holland-Batt), Poetry Chicago (ed. Robert Adamson), and Poetry Review Ireland. She was shortlisted for a 2017 Keats-Shelley Poetry Prize UK and she has published three poetry collections, In Front of a Comma (Poets Union 2006), N’ombre (Vagabond 2007) and Swallow (Five Islands 2010). She lives in London.

Claire Potter ’s most recent poetry publications have appeared in The Fremantle Press Anthology of Western Australian Poetry (edited by John Kinsella and Tracy Ryan), Best Australian Poems 2016 (ed. Sarah Holland-Batt), Poetry Chicago (ed. Robert Adamson), and Poetry Review Ireland. She was shortlisted for a 2017 Keats-Shelley Poetry Prize UK and she has published three poetry collections, In Front of a Comma (Poets Union 2006), N’ombre (Vagabond 2007) and Swallow (Five Islands 2010). She lives in London. Preparations for Departure

Preparations for Departure Mark O’Flynn’s most recent collection of poems is Shared Breath, (Hope Street Press, 2017). He has published a collection of short stories as well as four novels. His latest The Last Days of Ava Langdon (UQP, 2016) has been shortlisted for the 2017 Miles Franklin Award.

Mark O’Flynn’s most recent collection of poems is Shared Breath, (Hope Street Press, 2017). He has published a collection of short stories as well as four novels. His latest The Last Days of Ava Langdon (UQP, 2016) has been shortlisted for the 2017 Miles Franklin Award. Robbie Coburn was born in Melbourne and grew up on his family’s farm in Woodstock, Victoria. His poems have been published in various journals and magazines including Poetry, Cordite, The Canberra Times, Overland and Going Down Swinging, and his poems have been anthologized. His first collection, ‘Rain Season’, was published in 2013 and a second collection titled The Other Flesh is forthcoming. He lives in Melbourne.www.robbiecoburn.com.au

Robbie Coburn was born in Melbourne and grew up on his family’s farm in Woodstock, Victoria. His poems have been published in various journals and magazines including Poetry, Cordite, The Canberra Times, Overland and Going Down Swinging, and his poems have been anthologized. His first collection, ‘Rain Season’, was published in 2013 and a second collection titled The Other Flesh is forthcoming. He lives in Melbourne.www.robbiecoburn.com.au Constitution

Constitution Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body

Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body Kate

Kate Adam Day is the author of the collection of poetry,

Adam Day is the author of the collection of poetry,  A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work

A Writing Life: Helen Garner and Her Work  Lindsay Tuggle has been widely published in journals and anthologies, including: Cordite, Contrapasso, HEAT, Mascara, Rabbit, and The Hunter Anthology of Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry(2016). She was short-listed for the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s International Poetry Prize, judged by Simon Armitage. Her work has been recognised by major literary awards, including: the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2015), the Val Vallis Award for Poetry (second prize 2009, third prize 2014), and the Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2016, longlisted 2014). Her first collection, Calenture, is forthcoming with Cordite Publishing. The manuscript evolved from residential writing fellowships awarded by institutions including the Australian Academy of the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and the Mütter Museum of Philadelphia. Tuggle also writes on intersections of poetry and science. The University of Iowa Press’s Whitman Series invited her first book, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America (forthcoming in 2017). She wrote a chapter on ‘Poetry and Medicine’ for Cambridge University Press’sWhitman in Context (2017). She teaches literary studies at Western Sydney University.

Lindsay Tuggle has been widely published in journals and anthologies, including: Cordite, Contrapasso, HEAT, Mascara, Rabbit, and The Hunter Anthology of Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry(2016). She was short-listed for the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s International Poetry Prize, judged by Simon Armitage. Her work has been recognised by major literary awards, including: the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2015), the Val Vallis Award for Poetry (second prize 2009, third prize 2014), and the Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2016, longlisted 2014). Her first collection, Calenture, is forthcoming with Cordite Publishing. The manuscript evolved from residential writing fellowships awarded by institutions including the Australian Academy of the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and the Mütter Museum of Philadelphia. Tuggle also writes on intersections of poetry and science. The University of Iowa Press’s Whitman Series invited her first book, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America (forthcoming in 2017). She wrote a chapter on ‘Poetry and Medicine’ for Cambridge University Press’sWhitman in Context (2017). She teaches literary studies at Western Sydney University. Adolfo Aranjuez is editor of Metro, subeditor of Screen Education, and a freelance writer, speaker and dancer. He has edited for Voiceworks and Melbourne Books, and been published in Right Now, The Lifted Brow, The Manila Review, Eureka Street and Peril, among others. Adolfo is one of the Melbourne Writers Festival’s 30 Under 30. http://www.adolfoaranjuez.com

Adolfo Aranjuez is editor of Metro, subeditor of Screen Education, and a freelance writer, speaker and dancer. He has edited for Voiceworks and Melbourne Books, and been published in Right Now, The Lifted Brow, The Manila Review, Eureka Street and Peril, among others. Adolfo is one of the Melbourne Writers Festival’s 30 Under 30. http://www.adolfoaranjuez.com Writing to the Wire

Writing to the Wire Shastra Deo was born in Fiji, raised in Melbourne, and lives in Brisbane. She holds a Bachelor of Creative Arts in Writing and English Literature, First Class Honours and a University Medal in Creative Writing, and a Master of Arts in Writing, Editing and Publishing from The University of Queensland. Her work has appeared in Cordite, Peril, Uneven Floor, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of the 2016 Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize; her debut collection, The Agonist, is forthcoming from UQP in September 2017.

Shastra Deo was born in Fiji, raised in Melbourne, and lives in Brisbane. She holds a Bachelor of Creative Arts in Writing and English Literature, First Class Honours and a University Medal in Creative Writing, and a Master of Arts in Writing, Editing and Publishing from The University of Queensland. Her work has appeared in Cordite, Peril, Uneven Floor, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of the 2016 Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize; her debut collection, The Agonist, is forthcoming from UQP in September 2017. Mindy Gill completed her Honours in Creative Writing at QUT. She has won the Tom Collins Poetry Prize, a Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Voiceworks, Tincture, Hecate, Australian Poetry Journal, and Island Magazine. She is an editor at Peril Magazine.

Mindy Gill completed her Honours in Creative Writing at QUT. She has won the Tom Collins Poetry Prize, a Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Voiceworks, Tincture, Hecate, Australian Poetry Journal, and Island Magazine. She is an editor at Peril Magazine. Laura McPhee-Browne is a writer and social worker from Melbourne, Australia. She is currently working on what she hopes will be her first book, ‘Cooee’, a collection of echo stories inspired by the short fiction of her favourite female writers.

Laura McPhee-Browne is a writer and social worker from Melbourne, Australia. She is currently working on what she hopes will be her first book, ‘Cooee’, a collection of echo stories inspired by the short fiction of her favourite female writers. Paul Dawson’s first book of poems, Imagining Winter (IP, 2006), won the IP Picks Best Poetry Award in 2006, and his work has been anthologized in Contemporary Asian Australian Poets (Puncher & Wattmann, 2013), Harbour City Poems: Sydney in Verse 1888-2008 (Puncher & Wattmann, 2009), and the Newcastle Poetry Prize Anthology, 2016 (Hunter Writers Centre, 2016). Paul teaches in the School of the Arts and Media at the University of New South Wales.

Paul Dawson’s first book of poems, Imagining Winter (IP, 2006), won the IP Picks Best Poetry Award in 2006, and his work has been anthologized in Contemporary Asian Australian Poets (Puncher & Wattmann, 2013), Harbour City Poems: Sydney in Verse 1888-2008 (Puncher & Wattmann, 2009), and the Newcastle Poetry Prize Anthology, 2016 (Hunter Writers Centre, 2016). Paul teaches in the School of the Arts and Media at the University of New South Wales. Annie Blake is an Australian writer who started school without knowing any English. She has been published in Verity La, Vine Leaves Literary Journal, About Place, Australian Poetry Journal and Cordite Poetry Review, forthcoming in Southerly and GFT Press. Her poem ‘These Grey Streets’ has been nominated for the 2017 Pushcart Prize. She is excited about the process of individuation, research in psychoanalysis, philosophy and cosmology. She is a former teacher who lives in Melbourne with her family. She blogs at annieblakethegatherer.blogspot.com

Annie Blake is an Australian writer who started school without knowing any English. She has been published in Verity La, Vine Leaves Literary Journal, About Place, Australian Poetry Journal and Cordite Poetry Review, forthcoming in Southerly and GFT Press. Her poem ‘These Grey Streets’ has been nominated for the 2017 Pushcart Prize. She is excited about the process of individuation, research in psychoanalysis, philosophy and cosmology. She is a former teacher who lives in Melbourne with her family. She blogs at annieblakethegatherer.blogspot.com Jessica Dionne lives in North Carolina and is currently pursuing an MA in Literature from The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She recently presented poems at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association annual conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and her work has been featured in The Longleaf Pine, Luna Luna Magazine, and Pour Vida Zine, and is forthcoming in The Mayo Review, and Rust + Moth.

Jessica Dionne lives in North Carolina and is currently pursuing an MA in Literature from The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She recently presented poems at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association annual conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and her work has been featured in The Longleaf Pine, Luna Luna Magazine, and Pour Vida Zine, and is forthcoming in The Mayo Review, and Rust + Moth. Exhibits of the Sun

Exhibits of the Sun We Need New Names

We Need New Names CB Mako is a member of West Writers Group and art student at Footscray Community Arts Centre.

CB Mako is a member of West Writers Group and art student at Footscray Community Arts Centre.

Fragments

Fragments Annihilation of Caste

Annihilation of Caste Hasti Abbasi holds a BA and an MA in English Literature. She recently submitted her PhD thesis on Dislocation and Remaking Identity in Australian and Persian Contemporary Fictions. Her work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Antipodes, Southerly, Verity La, AAWP, and Bareknuckle Poet Journal of Letters, amongst others.

Hasti Abbasi holds a BA and an MA in English Literature. She recently submitted her PhD thesis on Dislocation and Remaking Identity in Australian and Persian Contemporary Fictions. Her work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Antipodes, Southerly, Verity La, AAWP, and Bareknuckle Poet Journal of Letters, amongst others. Jenna Cardinale writes poems. Some of them appear in Verse Daily, Pith, The Fem, and H_NGM_N. Her latest chapbook, A California, will be published by Dancing Girl Press in 2017. She lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Jenna Cardinale writes poems. Some of them appear in Verse Daily, Pith, The Fem, and H_NGM_N. Her latest chapbook, A California, will be published by Dancing Girl Press in 2017. She lives in Brooklyn, NY. Darlene Silva Soberano is a young Filipino poet who immigrated to Australia at an early age. She is currently completing a Bachelor of Arts at Deakin University. This is her first published poem. You can find her on Twitter at @drlnsbrn

Darlene Silva Soberano is a young Filipino poet who immigrated to Australia at an early age. She is currently completing a Bachelor of Arts at Deakin University. This is her first published poem. You can find her on Twitter at @drlnsbrn R. D. Wood is of Malayalee and Scottish descent and identifies as a person of colour. He has had work published or that is forthcoming from Southerly, Jacket2, Best Australian Poetry, JASAL and Foucault Studies. His most recent collection of poems is Land Fall

R. D. Wood is of Malayalee and Scottish descent and identifies as a person of colour. He has had work published or that is forthcoming from Southerly, Jacket2, Best Australian Poetry, JASAL and Foucault Studies. His most recent collection of poems is Land Fall Roland Leach has three collections of poetry, the latest My Father’s Pigs published by Picaro Press. He is the proprietor of Sunline Press, which has published nineteen collections of poetry by Australian poets. His latest venture is Cuttlefish, a new magazine that includes art, poetry, flash fiction and short fiction.

Roland Leach has three collections of poetry, the latest My Father’s Pigs published by Picaro Press. He is the proprietor of Sunline Press, which has published nineteen collections of poetry by Australian poets. His latest venture is Cuttlefish, a new magazine that includes art, poetry, flash fiction and short fiction. Bull Days

Bull Days