Gentle and Fierce

Gentle and Fierce

by Vanessa Berry

Giramondo

ISBN 9781925818710

Reviewed by FERNANDA DAHLSTROM

Gentle and Fierce is a book of essays that provides glimpses of Sydney author Vanessa Berry’s life by dissecting her encounters with non-human animals in various contexts – in the household, in captivity, in art and in the form of ornamental objects. Through Berry’s encounters with animals, we piece together her life as a city-dweller and an intellectual, a solitary who is as much an observer of other humans as of the animal world. Her essays allude to the destruction of the natural world and the marginalisation of other life forms by humans as Berry strives to connect with nature despite a paucity of opportunities to do so.

The author begins by sharing that her first name means ‘butterfly’ and that knowing this as a child ‘attunes you to their presence’ (p.7). She recalls expecting adulthood to be ‘a time of emergence, as if from a cocoon, into a life where I was colourful and unconstrained’ only to be disappointed at finding herself, in her twenties, ‘still as ponderous as ever, given to reticence in social situations and to slinking away alone’ (p11). The author’s introversion is a recurring theme. As a child she realises that the ideal is to be extroverted; instead, as a young woman she thinks of herself as a spider, eavesdropping on the conversations around her and writing down lines in her notebook, ‘Every detail stuck in my web.’ (p.125)

Berry repeatedly evokes the folly of humans. The notoriously aggressive myna bird was introduced in the nineteenth century to control the insects in crop fields, only to prove more interested in eating the produce itself. She reads of how palm oil, paper and rubber industries are affecting Sumatran forests, the habitat of tigers, prompting her to reflect:

As I look over the list these substances seethe around me, the pantry dribbling palm oil, the papers dusty and yellowing on the shelves. The rubber soles of shoes sit heavy in the depths of the wardrobe. Outside, car tyres crackle over the road. (p.20)

In ‘Rabbit Island’ she recalls visiting a Japanese island that serves as a sanctuary for rabbits in the months following the Fukushima disaster. The essay alludes to the issue of vivisection but does not delve into it, instead tracing the theme of rabbits in her own life, recalling a pet rabbit, which people joked was edible. She writes:

That was difficult for me to understand. Having been a vegetarian for decades I made little distinction between food animals and companion animals in terms of what kind of soul they might or might not have. (p.53)

In this way, Berry’s observations about the reprehensible attitudes and behaviours of humans towards the animal world are made in a way that is restrained and non-didactic. She implicates herself in her criticisms of the mores of human social life, where animals are relegated largely to museums and fairy tales as she lives a life where animals play a largely symbolic and abstract role. Her childhood memories of animals are not of wild or even domestic creatures, but of the badger and the toad in a story and a stuffed bear in a museum exhibit. She describes various kitsch representations of animals: porcelain figurines of horses, dogs and cats, a glass fish, a polystyrene bear and a ceramic crocodile, and acknowledges, ‘it is difficult to reconcile their abundance as mascots, toys or decorations, with knowledge of how their real counterparts have been affected by human encroachment on their lives and habitats.’ (p.104)

‘The Fly’ strings together a series of anecdotes from her life using the presence of flies as the organising principle. A reference to a fly’s buzz in an Emily Dickinson poem read in the late 1990s. A fly alighting on her hand, while listening to a talk by Elizabeth Jolley, preventing her from raising the hand in response to a question. A fly buzzing around an acupuncture clinic and another one crawling across a pub table. The ubiquity of flies during a bush fire season.

Some of the essays tell stories whose connection with the animal under consideration is tenuous. In ‘The Word of a Snail’, Berry reflects on her lifelong love of the work of Sylvia Plath and relates the experience of visiting the poet’s grave, where messages written to her by fans were being crawled over by snails. Just when anecdotes like these are starting to feel glib, Berry plunges us into the horrors of the 2020 bush fires which killed over a billion animals with ‘Animal Chronicle II’, which was for me the highlight of the book. In that essay, Berry imagines, amidst the inferno, ‘a dystopian world of only cities and burning forests, where animals were extinct or rarely seen, only to be remembered through objects’ (p.155). But just how much imagining is required for this scenario? This dystopia seems to be exactly the world that we have been reading about, where humans fetishise cute representations of animals while remaining either oblivious to or uncaring of what is truly befalling the animal world.

Curiously absent from Berry’s selections is any mention of the practice of factory farming, in which billions of animals are mutilated and slaughtered for profit every year in what has been called ‘the animal holocaust’. Nor does she mention the fact that the majority of mammals on earth are now livestock and the vast majority of birds, farmed poultry, an omission so glaring that it must be deliberate. Perhaps the absence of any discussion of these facts is a reflection of the lack of awareness of or attention to these issues in most echelons of human society. Unlike the ornamental, domestic, taxidermised and wild animals to which Berry dedicates space, the victims of factory farming are out of sight and out of mind.

However, Berry does explain, in ‘Animal Chronicle II’, what is termed ‘shifting baseline syndrome’, the phenomenon of each generation taking its own youth as its point of reference for ecological diversity. In this way, she joins the dots with her earlier essays, many of which dwelled on the presence of insects and other critters during various scenes of her youth. How many of these mundane experiences will future generations share?

Gentle and Fierce is a quiet but absorbing and thought-provoking work that approaches relations between humans and animals from many angles. Berry’s writing is languid, evocative and highly literate and the generous sprinkling of literary references is one of its most appealing features. Each essay is illustrated with a drawing of an animal done by the author, who is also an artist and zine maker.

FERNANDA DAHLSTROM is a writer, editor and lawyer who lives in Brisbane. She completed a Master of Arts at Deakin University in 2017. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Overland, Kill Your Darlings and Art Guide.

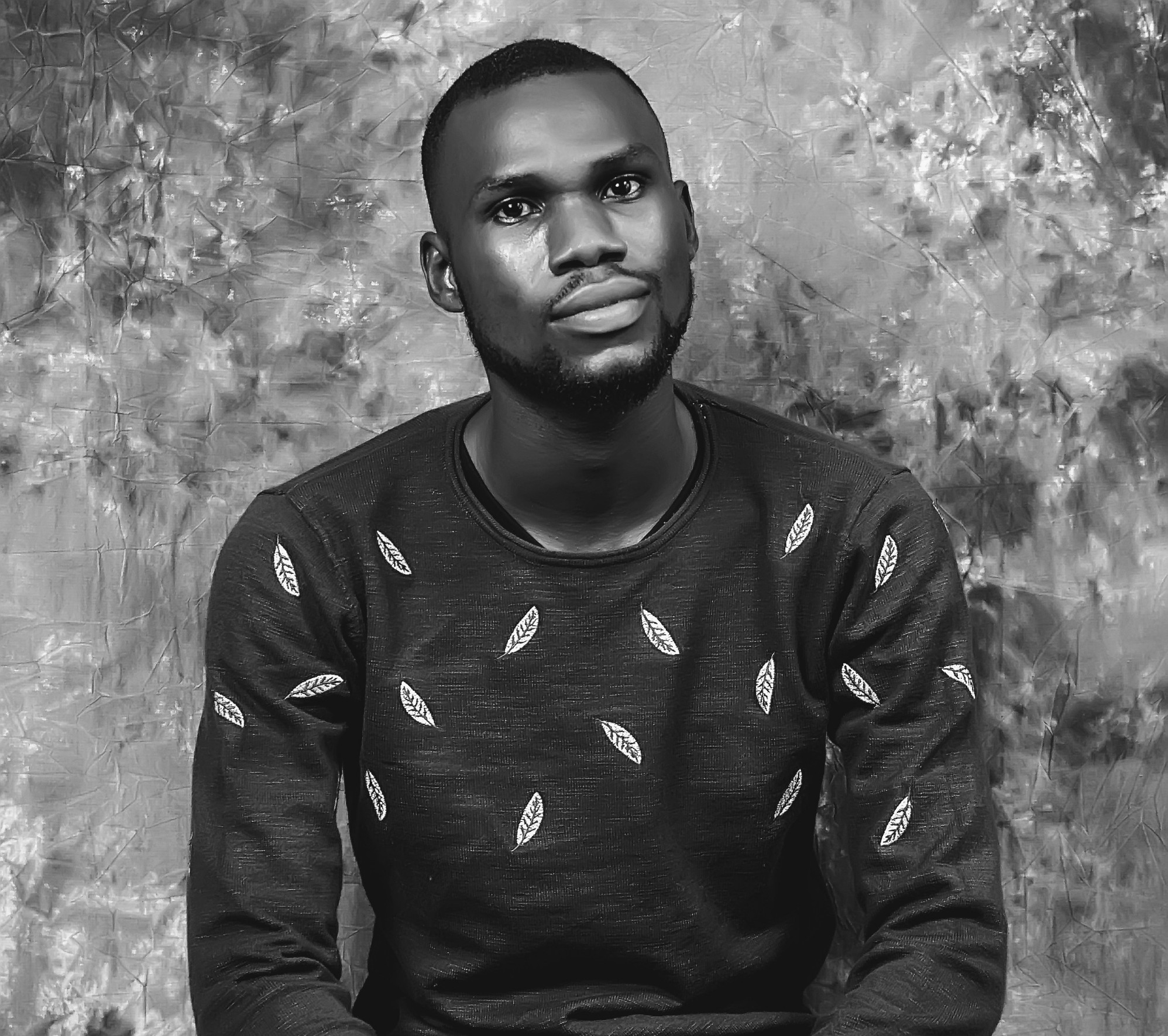

Ojo Taiye is a young Nigerian poet who uses poetry as a handy tool to hide his frustration with society. He also makes use of collage and sample technique. He is the winner of many prestigious awards including the 2021 Hay Writer’s Circle Poetry Competition, 2021 Cathalbui Poetry Competition, Ireland.

Ojo Taiye is a young Nigerian poet who uses poetry as a handy tool to hide his frustration with society. He also makes use of collage and sample technique. He is the winner of many prestigious awards including the 2021 Hay Writer’s Circle Poetry Competition, 2021 Cathalbui Poetry Competition, Ireland. Monique Lyle is a DCA candidate with the writing centre at Western Sydney University. She is currently completing her first manuscript, The Park, which explores her experiences growing up in Sydney Housing Commission in the 90’s. Recently her work has appeared in Overland, Flash Cove, Otoliths, Plumwood Mountain and also Dance Research.

Monique Lyle is a DCA candidate with the writing centre at Western Sydney University. She is currently completing her first manuscript, The Park, which explores her experiences growing up in Sydney Housing Commission in the 90’s. Recently her work has appeared in Overland, Flash Cove, Otoliths, Plumwood Mountain and also Dance Research. Lisa Nan Joo lives on Gadigal land and is an emerging writer of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. Her work has previously appeared in Kill Your Darlings, Strange Horizons, Meniscus, Seizure Online and Spineless Wonders.

Lisa Nan Joo lives on Gadigal land and is an emerging writer of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. Her work has previously appeared in Kill Your Darlings, Strange Horizons, Meniscus, Seizure Online and Spineless Wonders. Lawdenmarc Decamora is a Best of the Net and Pushcart Prize-nominated writer with work published in 23 countries around the world. He is the author of three book-length poetry collections, Love, Air (Atmosphere Press, 2021), TUNNELS (Ukiyoto Publishing, 2021), and Handsome Hope which is forthcoming from Yorkshire Publishing in 2022. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in places like The Common, The Seattle Review, Columbia Review, North Dakota Quarterly, California Quarterly, Cordite Poetry Review, AAWW’s The Margins, and elsewhere. His poetry will be anthologized in The Best Asian Poetry 2021 and had recently appeared in the best-selling Meridian: The APWT Drunken Boat Anthology of New Writing. In the UK, Lawdenmarc’s poetry was long-listed for The Alpine Fellowship Writing Prize 2021 and shortlisted for Aesthetica Creative Writing Award 2021 (Aesthetica Magazine). He was an August 2021 alumnus of the Tupelo Press 30/30 Project of the US-based Tupelo Press, and is also a member of the Asia Pacific Writers & Translators (APWT). He lives in the Philippines where he teaches literature at the oldest existing Catholic university in Asia, the University of Santo Tomas (UST).

Lawdenmarc Decamora is a Best of the Net and Pushcart Prize-nominated writer with work published in 23 countries around the world. He is the author of three book-length poetry collections, Love, Air (Atmosphere Press, 2021), TUNNELS (Ukiyoto Publishing, 2021), and Handsome Hope which is forthcoming from Yorkshire Publishing in 2022. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in places like The Common, The Seattle Review, Columbia Review, North Dakota Quarterly, California Quarterly, Cordite Poetry Review, AAWW’s The Margins, and elsewhere. His poetry will be anthologized in The Best Asian Poetry 2021 and had recently appeared in the best-selling Meridian: The APWT Drunken Boat Anthology of New Writing. In the UK, Lawdenmarc’s poetry was long-listed for The Alpine Fellowship Writing Prize 2021 and shortlisted for Aesthetica Creative Writing Award 2021 (Aesthetica Magazine). He was an August 2021 alumnus of the Tupelo Press 30/30 Project of the US-based Tupelo Press, and is also a member of the Asia Pacific Writers & Translators (APWT). He lives in the Philippines where he teaches literature at the oldest existing Catholic university in Asia, the University of Santo Tomas (UST). Jennifer Compton lives in Melbourne and is a poet and playwright who also writes prose. Her 11th book of poetry, the moment, taken was published by Recent Work Press in 2021.

Jennifer Compton lives in Melbourne and is a poet and playwright who also writes prose. Her 11th book of poetry, the moment, taken was published by Recent Work Press in 2021. Greg Page is a Koori Poet from the La Perouse community at Kamay (Botany Bay). He holds an M.A. in Creative Writing from UTS in Sydney and has been published in the Australian Poetry Journal and the Koori Mail. He lives on unceded Bidjigal land. Dox him at

Greg Page is a Koori Poet from the La Perouse community at Kamay (Botany Bay). He holds an M.A. in Creative Writing from UTS in Sydney and has been published in the Australian Poetry Journal and the Koori Mail. He lives on unceded Bidjigal land. Dox him at  Debbie Lim lives in Sydney. Her work has appeared in anthologies including regularly in the Best Australian Poems series (Black Inc.) and Contemporary Asian Australian Poets (Puncher & Wattmann). Recent work appears in Westerly, Island, Rabbit, Overland and the Willowherb Review (UK). Her chapbook is Beastly Eye (Vagabond Press) and she is working on a full-length collection. She was a Mascara Don Bank Poet-in-Residence in 2020–2021.

Debbie Lim lives in Sydney. Her work has appeared in anthologies including regularly in the Best Australian Poems series (Black Inc.) and Contemporary Asian Australian Poets (Puncher & Wattmann). Recent work appears in Westerly, Island, Rabbit, Overland and the Willowherb Review (UK). Her chapbook is Beastly Eye (Vagabond Press) and she is working on a full-length collection. She was a Mascara Don Bank Poet-in-Residence in 2020–2021. Anisha Pillarisetty is a radio producer and presenter at Radio Adelaide and a journalist at On the Record, living on unceded Kaurna Yerta. She is currently in her third year of university studying creative writing and journalism.

Anisha Pillarisetty is a radio producer and presenter at Radio Adelaide and a journalist at On the Record, living on unceded Kaurna Yerta. She is currently in her third year of university studying creative writing and journalism. Zhang Meng, born in 1975, is a member of Shanghai Writers Association and has published five books of poetry.

Zhang Meng, born in 1975, is a member of Shanghai Writers Association and has published five books of poetry. Gentle and Fierce

Gentle and Fierce