Dr PIP NEWLING reads and writes on unceded Dharawahl Country. She has published memoir and essays, including

Knockabout Girl (Harper Collins, 2007).

Always was, always will be Aboriginal land.

March 30, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Murnane

Murnane

by Emmett Stinson

Melbourne University Publishing

ISBN: 9780522879469

Reviewed by SAMUEL COX

Emmett Stinson’s Murnane offers a critical and enlightening assessment of the Gerald

Murnane’s four late fictions, and through these incredibly self-reflexive works, a reading of

the eponymous author’s entire oeuvre. Stinson’s superb introduction gives way to chapter-

length considerations of Barley Patch (2009), A History of Books (2010), A Million Windows

(2014) and Border Districts (2017), before concluding with an assessment of Murnane’s ‘late

style’. The study confirms this late style is intensely introspective and genre-bending –

somewhere between novel, memoir and essay – as Murnane seeks to retrospectively reform

and recontextualise his entire body of work.

If this then provides a faint outline of Stinson’s method and the briefest summary of his

results, I would like to focus on pursuing what I see as the two most intriguing and important

lines of investigation that underly Stinson’s study and make it utterly compelling: his

exploration of the entirely ‘singular’ phenomenon that is Murnane, and, deeply interrelated,

his recurring pursuit of the enigma that is the author’s lack of widespread recognition in the

country of his birth.

I’ll begin with the second question, as it appears, initially at least, the more straightforward to

answer. Whilst noting Murnane’s unfashionable peculiarities, which form the bones of this

study, Stinson rightly invokes Patrick White’s criticism of Australia’s aesthetic inclination

towards ‘the dreary, dun-coloured offspring of journalistic realism’ (qtd. in Stinson 15). From

the Ern Malley affair, through to the harsh local critiques of White’s early works, and similar

treatment that influenced Randolph Stow’s decision to leave the country, the cultural

philistinism of settler-colonial Australia has long cast a dark shadow over any emergent local

avant-garde. Overall, literary modernism in Australia remains a critical frame that, if not

abhorred, then has largely been ignored.

An intriguing counterpoint to Murnane is David Malouf, a writer of a similar era who achieved widespread literary fame and popularity. If we admit that Malouf’s use of modernist techniques

has a lighter and less experimental (and thus more palatable) touch, then we can also see that to answer this question, we must return to the first line of investigation I proposed and seek out a deeper exploration of what Stinson repeatedly refers to as Murnane’s ‘idiosyncratic’ and ‘singular’ nature. Brilliantly characterising Murnane as ‘a homemade avant-garde of one’ (103), Stinson reveals the unique breadth of literary influences on Murnane’s work, but it is the unique ‘homemade’ peculiarities that appear essential to understanding the riddle that is Gerald Murnane.

Stinson establishes that it is precisely Murnane’s distance – not just today but across his

career – from intellectual trends, his singular even perverse pursuits, which have opened him

to criticism; however, as his body of work has grown, these traits have increasingly set him

apart as his obsessive pursuits have made him an original, adding a unique chapter to the

literary explorations of the human condition.

It should be noted that, on the surface, many of Murnane’s concerns appear to align with the

well-established conventions of literature. J.M. Coetzee has described Murnane as a ‘radical

idealist’ and his relentless probing into the power and truth of inner imaginative worlds is not,

in and of itself, unique. Indeed, Murnane’s insistent interest in the imaginative life is in many

ways one of the timeless pursuits of art and literature; rather, it is the inimitable

idiosyncrasies of Murnane that make him utterly unique. What rises irrepressibly from

Stinson’s work is the deeply paradoxical elements that shape Murnane and fuel his fiction.

Murnane is a novelist who ‘never tried to write fiction’ (21); an avant-garde

modernist who has barely left his own state, let alone the country; a working-class writer who

persistently aestheticises reality; an author whose embrace of the ordinary often leads the

reader into sensing the mystical qualities of the extraordinary; an experimental author who is

a stickler for ‘traditional grammar’ (qtd. in Stinson 33). He is a writer who roundly criticises

literary criticism and yet Stinson notes that ‘he is technically the first author of a critical work

about the complete oeuvre of Murnane’ (16). Despite his deeply introspective explorations,

and his endless returning to the same images, scenes and themes, the authorial self remains

remote and inaccessible for Murnane. Stinson isolates a moment at the conclusion of

Murnane’s A Million Windows that represents this truth when the narrator glances up at the

window of a writer: ‘I looked up and saw… a window and behind it a drawn blind. In short, I

learned nothing’ (qtd. in Stinson 67).

This moment is echoed in the 2019 interview with Stinson that is included as something of an

afterword. Murnane retells how he became convinced that a filmmaker who had bought the

rights to Inland didn’t understand the book, so he set out to explain it: three quarters of his

way down the page he realised that even he ‘wasn’t on the right track’ admitting that, ‘I don’t

think I even know what it’s about’ (qtd. in Stinson 116). It is not everyone who is going to

read a Murnane book and enjoy it. Certainly, many in Australia weren’t ready when he started

his career. Indeed, as Stinson notes, some have even been repulsed by his interest in the

obsessions and perversions of lonely, monastic men. His work pursues a

relentless, at times forensic examination of the self through writing, even as he recurringly

acknowledges that this is in part a futile exercise: the writing self is multitudinous; both true

and false.

A casual reader who might have only encountered Murnane’s older works, particularly his

most well-known and influential work, The Plains, might question Stinson’s decision to focus

on his late career. It could even be considered – unsurprisingly, given Stinson’s approach is

deeply informed by the author’s work – something of a Murnanian conceit. However, what

uniquely emerges in Stinson’s study is how his late career works create a mirage-like

refraction of his early career works that radically reframes them. For example, aspects of The

Plains, like the filmmaker’s literary patron and its isolated ‘secular monastery’ of a manor

(Stinson 58), become linked to longstanding and recurring concerns of Murnane’s fiction.

Finally, Stinson presents a detailed argument that Murnane’s final novel, Border Districts,

reconstructs The Plains as it was originally intended – as part of a dyad or textual diptych.

New readings of The Plains are offered and whether they are superior appears beside the

point. Instead, Stinson forces us to reconsider The Plains, and indeed Murnane’s entire

oeuvre, through what he terms the ‘retrospective intention’ of Murnane’s late career works, as

the aging author attempts the daunting task of shaping his disparate body of work into the

‘seeming coherence’ of an ‘aesthetic totality’ (81). If, in reality, this totality ultimately lies

always just out of reach, like the distant horizon of the plains, then Stinson shows us that its

simulacrum is given form by its continual refraction throughout Murnane’s fiction.

We inevitably return to the lingering question of his unsure place within the literary

canon of this country. In Nicholas Birns estimation he is the ‘most Australian of writers’ and

‘the least Australian of writers’ (qtd. in Stinson 90). This is a man who has barely left the

state of Victoria, is obsessed with horse racing and currently lives in the small rural town of

Goroke in the Wimmera, Victoria. As J.M. Coetzee has noted, the underlying dialectics of

Murnane’s narrators can be traced back to the lingering imprint of Australian Irish

Catholicism. Many of the landscape images that recur across his fiction are characteristically

Australian in nature. And yet, the authors he is in conversation with not only remain classed

as ‘difficult’ by most Australian readers, but they are also distant from these shores in both

space, and, increasingly, time – Joyce, Rilke, Proust, Emily Bronte, Jorge Luis Borges, Italo

Calvino, Henry James, are a just a few that Stinson recognises.

Murnane’s long and persistent struggles with publication and readership over his career, pose

big questions over whether we can accept and support challenging and self-critical art in this

country, even when it is unfashionable. A further problematic is that it is not just new and

emerging voices who struggle for readership and attention – Australian literature as a broad

category remains criminally underread and understudied. As Ivor Indyk, Murnane’s editor at

Giramondo, has noted, ‘most of our literary tradition is out of print, undertaught and largely

unknown to the Australian public.’ It was Giramondo’s unwavering support of Murnane that

brought him out of his self-imposed retirement and enabled these four late career novels to

emerge in their desired form. If Giramondo stands out like a beacon in an Australian literary

landscape that has lost some of its lustre, then so too does Gerald Murnane – the ‘homemade

avant-garde of one’ who, after years of persistence in the wilderness, is enjoying a well-

deserved late career resurgence.

Stinson’s treatment is deeply sympathetic and yet even this importantly represents the current

moment that seemingly demands a revaluation of Murnane’s work. His claim that Murnane is

‘the most original and most significant Australian author of the last fifty years’ (104) is bold,

but international acclaim and murmurings of Nobel Prize nominations surely mean even local

critics cannot deny that Murnane now must have a place in the conversation. For those

seeking an entry point into the complexities of Murnane and his fiction, Emmett Stinson’s

Murnane presents the clear place to start.

SAMUEL COX teaches Australian literature at the University of Adelaide. His work has been published in JASAL, The Saltbush Review, Westerly, ALS, Motifs, SWAMP and selected for Raining Poetry in Adelaide. In 2022, he received the ASAL A.D. Hope Prize. He was awarded the Heather Kerr Prize, and was a joint winner of Australian Literary Studies PhD Essay Prize with Evelyn Araluen.

March 29, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

H.D. (Hilda Doolittle)

by Lara Vetter

Reaktion Books

ISBN:9781789147599

Reviewed by NAOMI MILTHORPE

It may say more about my own tastes than about the culture more broadly, but most of my reading in the past months has been about misunderstood and multifaceted women. Lara Vetter’s slim critical life of the modernist poet H.D. has slid snugly between Anna Funder’s ponderous counterfiction Wifedom (2023), Katharine M. Briggs’s neglected 1963 witchy Scots fairy tale, Kate Crackernuts, and Nancy Mitford’s 1952 fizzing biography of Louis XV’s official mistress, Madame de Pompadour. It’s important to state at the outset that Vetter’s book is fundamentally unlike any of these books – neither ponderous nor witchy nor particularly fizzing. Yet in focusing on a woman who thrived exploring experimental modes of writing and relished occupying new forms of identity and relationship, it offers an engrossing contrast to the picture these other books offer, of the way history, circumstance, and choice, impact upon women’s lives. H.D. has been taken as a biographical subject by a number of earlier writers, including most recently Francesca Wade in her excellent 2021 group biography Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars. As Wade writes, ‘A biography offers one version of a life, and H.D. lived several.’(1) In living several ‘lives’ – or as Lara Vetter suggests, in living a life that flourished through contradiction and multiplicity – H.D. is also a fascinating subject for readers interested in what it takes to live, thrive, and create through cataclysmic social and political change.

She was born Hilda Doolittle in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania in 1886, the daughter of Charles, an astronomy professor and Helen, a musician and painter. Hilda was the only daughter of six children. The Doolittles were members of the Moravian church, an evangelical German Christian sect that focused on community, family, and ritual, including a strong devotion to music. H.D.’s early life – portrayed by her in autobiographical novels like HERmione, written in the late twenties but published in 1981 – was bounded by both the pleasures and frustrations of this life. As a scientist her father encouraged his children to closely observe nature in their rambling garden and the surrounding forest. Hilda’s elder brother Eric also taught astronomy and tutored his siblings in botany and ecology, which Hilda was fascinated by: ‘There were things under things, as well as things inside things.’(2) Helen passed on her skills in music and the arts, with Hilda playing piano and participating in musicals and Shakespeare performances. Hilda taught herself ancient Greek; throughout her life she remained deeply inspired by Greek history and myth. Hilda enrolled in Bryn Mawr College, studying the classics, and meeting Marianne Moore and William Carlos Williams along the way, but dropped out after three semesters to focus on her writing.

It was meeting the poet Ezra Pound, and the mystic and writer Frances Gregg – both fellow Pennsylvanians – that caused the first cataclysm of her early life. The three were caught in a tumultuous love triangle for several years. Pound called Hilda ‘Dryad’, and for him, she was a muse that haunted his early poems. Pound and Hilda became engaged and then broke it off. But the relationship with Frances Gregg was the more electrifying. Both Hilda and Gregg viewed sexuality and gender as non-binary, and both (at this time) were polyamorous. Pound went to Europe in 1908, and Hilda and Gregg followed in the summer of 1911. Although the romance ended (Gregg returned to the U.S. and married, a profound betrayal for Hilda), Pound and Hilda would stay in Europe for good, entangled in each other’s lives and writing until well into the thirties.

How Hilda became H.D. is literary legend, sketched by H.D.’s. earlier biographer Barbara Guest: Hilda, sitting with Pound in the tea room of the British Museum in 1912, showed him some poems. ‘But Dryad, this is poetry.’ Then, in his manner, he made some adjustments, and signed them off for her, scrawling H.D., Imagiste, at the bottom of the pages and posting them to Harriet Monroe at the then newly-established magazine, Poetry. (3) These poems – ‘Hermes of the Ways’, ‘Epigram’, and ‘Priapus’ – were published in January 1913 and Hilda, now H.D., became the figurehead for what Pound hoped would become a revolutionary literary movement, Imagism. He would expound these theories in one of his early aesthetic manifestos, ‘A Few Don’ts By An Imagiste’, as well as in some now-much-anthologized poems like ‘In a Station of the Metro’. H.D.’s husband Richard Aldington suggested, though, that Pound’s theories were ‘based on H.D.’s practice’ (4). While the literary notice was gratifying, H.D. was soon embarrassed by the ‘Imagiste’ moniker and asked Monroe to remove it from any subsequent poems she published. In 1916 her first collection, Sea Garden, was published, to both acclaim and puzzlement – especially over gender identity, for some reviewers veiled by those obscure initials. Throughout her life, H.D. would experiment with multiple nom-de-plumes, relishing in the simultaneous effacement and expansion of identity they offered.

It is still often for these early poems that H.D. is best known – poems like ‘Oread’, ‘Sea Garden’, and ‘Sea Rose’. The adjective ‘crystalline’, was attached to her poetry so doggedly that she began to resent it, especially given her later experiments with long form verse and prose. But as Vetter ably argues, reading H.D. only for the poems published in the 1910s risks understanding only a fraction of her life and writing, which were deeply intertwined and profoundly multifaceted. Vetter sees her as dramatically inconsistent, ‘swing[ing] wildly between poles’ of personality according to who is giving the account of her (5). But consistency of self is only a problem for the biographer, not for the liver of the life (as many of H.D.’s biographers, Vetter included, are well aware). As Vetter writes, ‘Work did not reflect life. Rather, she wrote her life into existence. She was ever-mindful that it is narratives that construct identity, and not the other way around.’(6) For H.D., who variously embraced and was challenged by the profound changes witnessed in the 20th century (cinema, psychoanalysis, total war, gender fluidity and sexual experimentation), the capacity to lose an identity, as she wrote in her 1928 poem ‘Narthex’, was ‘a gift’(7).

Vetter has previously published extensive scholarship on H.D.’s later work, especially her prose. As Vetter shows, any account of H.D.’s long and varied life needs to carefully weigh Imagism, which she left behind in the twenties, with her other creative endeavours and personal milestones. These include her writing for and about film, pursued in the pages of the landmark film journal Close Up but also through film-making such as in the avant-garde feature Borderline (1930) in which she acted opposite Paul Robeson; book length poems such as Trilogy, written in response to World War Two (published between 1942 and 1946), and Helen in Egypt (1961); her writing on Shakespeare (By Avon River, 1949) and Freud, with whom she entered analysis in 1931 (Tribute to Freud, 1954); and her autobiographical novels, such as Paint it Today, Asphodel, HERmione, and Bid Me to Live. Many of these novels – besides Bid Me to Live – remained unpublished in H.D.’s lifetime, which explains why her reputation was, for so long, based on the early poetry. But the novels provide rich evidence for her life, relationships, sexuality, and literary development; they also emphasize, as Vetter argues, ‘the self as object of narration’(8).

In her personal life – which H.D. viewed as a source of art – she was similarly uninterested in conventionality as it was defined in the early 20th century. Though married to, and living with, Aldington throughout the twenties, she pursued other romantic and sexual relationships with both men and women. Her daughter, Perdita, was the child of a relationship with Cecil Gray, a Scottish composer whom H.D. lived with in Cornwall in 1918, though Aldington was named on the birth certificate. But neither of these men were Perdita’s primary carer. Though she initially thought she might raise her daughter alone, at the end of the Great War Hilda met and began a relationship with the heiress and writer Bryher (Winifed Ellerman), who became her lifelong partner. Bryher and Hilda were, as Perdita later wrote, her two mothers (Vetter suggests Bryher may today likely have identified as transgender, having in 1919 been reassured by the sexologist Havelock Ellis that ‘she was only a girl by accident’(9)). The relationship was romantically and creatively nourishing – Bryher shared H.D.’s enthusiasm for film and travel – and, thanks to Bryher’s immense wealth, protected H.D. from the need to write for commercial reasons.

Anna Funder’s Wifedom is focused on the traps which heterosexual marriage, home keeping, and motherhood seem to lay for many, especially low-income women. In comparison, Vetter’s study shows the relative freedom H.D. enjoyed in pursuit of love and art. Where Funder portrays Eileen Orwell chained to the home, mucking out blocked toilets and making endless rounds of tea, devoted in unpaid servitude to the project of George Orwell’s writing, from which she was studiously erased, Vetter shows H.D. able to combine parenting, travelling, loving, and learning, with writing. Hilda was not bogged down in wifedom (neither, I should add, was Bryher, though both according to Perdita, were devoted parents). H.D.’s adherence to the first principle of art = life meant that she devoted her whole existence to creative and personal liberty. Of course, Bryher’s independent wealth, and the freedom of movement permitted to their white bodies, enabled their living largely unthreatened by the injustice and oppression central to, and ongoing beyond, the 20th century.

Part of why H.D. was forgotten by the academy following her death in the 1960s may have been her unclassifiability. By the end of her career, she could no longer be called simply an ‘Imagist’. But part of the reason she could be recovered by feminist researchers in the 70s and 80s was because she kept so much of her unpublished writing, and so many of her letters and notebooks. This is another point of comparison with Eileen Orwell, whose archival existence is, comparatively, slim. H.D. is a creation of paper, self-fashioned by her own autobiographical writing, and by her early deposit of a ‘shelf’ of manuscript papers at Yale’s Beinecke Library. Writing was H.D.’s motivation for living, and living fuelled her writing. As the poet Robert Duncan wrote in his monumental work, The H.D. Book, ‘she took whatever she could, whatever hint of person or design, colour or line, over into her “work”.'(10) It is fortunate that ongoing editing and publication since the 1980s by the publisher New Directions has made so much of her writing accessible to the general reader.

This ‘Critical Life’ of H.D. is necessarily an introductory one, especially given the wealth of published and unpublished material to cover. Vetter states from the outset that this book is intended for those mostly unfamiliar with H.D.’s life. Vetter manages the breadth and depth of materials with deftness, moving between archival and literary evidence to create a portrait of an individual who was totally unique but not at all one-dimensional. It is worth the attention for those who are interested in understanding this fascinating poet and her devotion to art.

Cited

1. Francesca Wade, Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars (Faber, 2020), p.38.

H.D., Tribute to Freud (Carcanet Press, 1997), p.21

2. Barbara Guest, Herself Defined: The Poet H.D. and her World (Doubleday, 1984).

3. Letter from Richard Aldington to Hilda Doolittle, 20 March 1929, in Lara Vetter, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), p.48.

4. Vetter, p.14.

5. Vetter, p.12.

6. Quoted in Vetter, p.15.

7. Vetter, p.101.

8. Quoted in Vetter, p.80.

9. Robert Duncan, The H.D. Book (University of California Press, 2011), p.242.

NAOMI MILTHORPE is Senior Lecturer in English at the School of Humanities. Her research interests centre on modernist, interwar and mid-century British literary culture, including most particularly the works of Evelyn Waugh. Naomi is currently completing a scholarly edition of Waugh’s 1932 novel Black Mischief, volume 3 of Oxford University Press’s Complete Works of Evelyn Waugh.

March 27, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

But The Girl

But The Girl

Jessica Yu

Penguin

ISBN: 9781761046148

Reviewed by HOLDEN WALKER

Jessica Zhan Mei Yu’s novel But The Girl (2023) is the story of protagonist and narrator “Girl”, as she embarks on a study abroad experience in the UK while immersing herself in British culture, contemplating her thesis, attempting to write her novel, and sharing her innermost thoughts with the reader. Yu’s novel possesses intimate autofictional narration, inspired by the oeuvre of Sylvia Plath and animated by intertextual allusions to her work. But The Girl explores various other subjects, from the creative process to the Malaysian-Australian experience; however, Yu brings personality and uniqueness to this novel by examining femininity in the postmodern and postcolonial context while commenting on the Australian “cultural cringe”.

In the context of Australian postcolonial literature, the “cultural cringe” was coined by literary critic A.A Phillips in a 1950 essay published in Meanjin literary magazine. The phenomenon describes a feeling of inferiority (felt particularly by Australians) in their own culture, including the feeling that Australian culture is embarrassing compared to other cultures. The Australian cultural cringe is well documented, even before the time of Phillips, as Henry Lawson provided an extensive diatribe in the preface to the 1894 edition of his Short Stories in Prose and Verse, stating that Australian writers were always in the shadow of British and American writers, and this frustrated him to no end (Rodrick, 1972).

Yu brings the same sentiment into the twenty-first century, breathing new life into a conversation as old as Australian literature itself. She writes:

“Feeling embarrassed about Australia’s provincial personality…had always been automatic to me and everyone I knew. A sense that we were no one, that we had nothing, that spending your whole life secretly trying to get away from the huge yawn that was Australia made you somehow important. Sometimes I wished my parents had immigrated somewhere else…” (p.17).

Yu’s writing, as evidenced by this excerpt, achieves a level of relatability that is likely to enchant many Australians, whether they arrived on Australian shores recently or their ancestral ties to the land span the entire history of the continent. Although we may not be able to point to a shared “Australian experience”, I imagine many have, at one stage, envied the marvel of Britain’s castles or been starry-eyed at the innovation of the capitalist mega-utopia that is America. After a while, our cultural signifiers no longer seem impressive, for “we are no one…we [have] nothing.”

Throughout the novel, Yu continues to explore the feeling of being unable to compete with the UK as an Australian, an emotional experience that may very well be symbolic of the immigrant experience in Australia. However, Girl challenges the notion that her postcolonial novel will inevitably draw from the ‘immigrant novel’ genre. Girl’s hesitation to write an ‘immigrant novel’ reminds me a lot of Nam Le’s ‘Love and Honour and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice’, a short story in which Le contemplates whether to write the inspiring ‘immigrant novel’ that is sure to be an instant classic, or something much more personal to him. For Girl, and by extension, Yu herself, But The Girl is a clear example of taking the second path, as she finds the intersection between postcolonial criticism and Sylvia Plath that is the subject of her thesis, and in a less explicit way, Yu’s novel.

As Girl contemplates how she will address Plath from a postcolonial perspective, Yu implements an arguably genius metafictional strategy by taking direct inspiration from Plath’s The Bell Jar and reinventing the novel to detail an Asian-Australian experience, all while keeping the autofictional style of Plath’s novel. In my view, But The Girl serves as a text that fills an emotional gap identified by the narrator, for although she finds The Bell Jar to be an incredibly powerful text that shaped her adolescent experience, it is clear that certain elements of Esther Greenwood’s narrative are unrelatable.

“When I read The Bell Jar for an undergraduate women’s writing class, I felt something new, brand new. It took me in from the start with its woozy charm and kidnapped my mind clean away. Which meant that it hurt like hell when she wrote about being ‘yellow as a Chinaman’ and worse when a few pages later there was ‘a big, smudgy-eyed Chinese woman . . . staring idiotically into my face’” (p.30)

In light of its flaws, Yu brings the feminine experience of coming of age in an academic setting into the twenty-first century, reinventing Plath in a way that caters better to modern, Australian, and diasporic readers. While there is no doubt that this updated classic will resonate with mainstream audiences, it should also serve as a love letter to Plath fans. Although I hate to disrespect Lawson and continue the vicious cycle of comparing Australian writers to their more recognised foreign predecessors, I can’t help but suggest that Australian literature has found its Sylvia Plath in Jessica Zhan Mei Yu, and in But The Girl, it has found its The Bell Jar.

Yu’s context, audience, and style deviate from Plath’s, who favoured a razor-sharp and occasionally even confrontational method of prose. Yu exhibits writing that is more contemporary and discursive, while still maintaining the “heart-on-her-sleeve” narrative style often associated with Plath. As a result, the novel provides detailed and intimate accounts of the experiences we often associate with coming of age, such as the struggle to establish our own identity. Girl often references the complicated intersection between being an educated woman who is a second-generation immigrant in the era of what she calls the “bimbo.”

Yu’s narrator identifies many facets of femininity, from the hyper-feminine facades of womanhood from her youth to the strong and empowered women she read about in her gender studies class. Girl struggles to find what types of femininity “fit” her, a feat complicated by her complex relationship with her family.

“Once, when I was walking home from dinner after an undergraduate class with some girls…A car full of young men had slowed to yell obscenities at us…one of the girls had stuck her finger up [at them]…I didn’t do anything to back her up. I reasoned that my parents hadn’t brought me to this country only for me to be found dead on a street somewhere near the university…unlike her parents, mine would never forgive me for dying on them.” (p.29)

Girl’s thought-provoking observations and accounts of how she navigates the world as an Asian-Australian woman in the process of defining her own understanding of womanhood serve as the perfect representation of her desire to examine Plath through a postcolonial lens. Readers witness Girl’s writing endeavours and the memories of her youth play out alongside each other, a sequence of juxtapositions that reveal the possibility that the inspiration for the narrator’s thesis had been hiding in plain sight all along.

Further, Yu also touches on the feelings of shame that plagued Girl’s adolescence and young adulthood, a facet that contributes significantly to the relatable tone of the novel and allows readers to see their own anxieties reflected in the text, eliciting greater reader engagement through the process of identification with the narrator. The theme of shame can also be tied into the concept of the “cultural cringe” that is explored in this novel, as Girl recounts a feeling of shame that came over her when she visited the Oxford campus in the UK, as it reminded her that Australia doesn’t have grand and prestigious schools like Oxford, just pastiches of them.

In a similar vein, Yu also explores the shame of femininity and how cultural perceptions of female adolescence impacted Girl’s self-esteem and ability to take herself seriously.

“When I was a teenager, I had thought that there was nothing more embarrassing in the whole world than being a teenage girl…And even more embarrassingly, no one cared about your humiliations because they didn’t matter that much anyway in the ‘grand scheme of things’…” (p.39)

The concepts come together to create a narrator who uses her life experiences as a catalyst to explore the complex emotions associated with coming of age in Australia, a subject matter that is bound to resonate with many readers, particularly those whose identities intersect with Girl’s in some way, be they PhD candidates, women, second-generation immigrants, or all of the above.

But The Girl is a testament to Jessica Zhan Mei Yu’s technical skills as a novelist, her appreciation for Sylvia Plath’s impact on emerging female writers, and the desire for women of diverse backgrounds to see themselves represented in the stories that define our youth.

In essence, I believe Yu achieves Girl’s dream of writing a ‘postcolonial novel’, arguably surpassing that ambition by also composing a text that has the potential to be highly influential on the emerging generation of young Australian women. A likely candidate for canonisation alongside Melina Marchetta’s Looking for Alibrandi and Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip, as well as being a stand-out contributor to the developing canon of Asian-Australian literature. In the same intertextual vein as the thematically similar Daisy & Woolf by Michelle Cahill, But The Girl is a title amongst a growing collection of texts that represent the contributions of Asian-Australian novelists to the historically white-dominated field of feminist literature.

Citations

Phillips, A 1950, The Cultural Cringe, Meanjin, viewed 17 March 2024,

Rodrick, C 1972, Henry Lawson: Autobiographical and Other Writings 1877-1922, Angus & Robertson, pp. 108–109.

HOLDEN WALKER is a literary critic and researcher of English literatures and writing from Yuin Country, NSW. He is a PhD candidate with the School of The Arts, English and Media at the University of Wollongong. His current research focus is on postmodern literary fiction and representations of the American Southwest.

March 15, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Slipstream

Slipstream

By Catherine Cole

Valley Press

ISBN: 9781915606341

Reviewed by CAROLINE VAN DE POL

As an admirer of Catherine Cole’s earlier novels, short story collections and memoir such as Sleep, Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark and The Poet Who Forgot, I awaited the publication of her new book, Slipstream: On Memory and Migration, with great anticipation. I was not disappointed. The book’s subject matter of memory and migration had its appeal for me as the daughter of an Irish immigrant and Australian mother.

The book was inspired by a flight between Australia and the UK when Cole sensed that she ‘had been infected in some way by a blight common amongst the children of migrants; that desire to experience a life missed in the country abandoned by my parents.’ (Cole, p. 12). A little while later during her Hong Kong stopover she enviously watched the locals laughing and sharing stories or pointing things out to one another. ‘The city teemed with families who seemed welded to their lives there. They went back a long way, I decided, generations and generations, or so it seemed to me on that humid, solitary day.’ (Cole, p.14)

Cole dedicated the book to her brother, Brian, who as a small boy, travelled with his parents in 1949 from Yorkshire in northern England to Australia under the Ten Pound Pom scheme to Bankstown in Sydney’s South Western suburbs. Brian died in 2022 so he didn’t see the book in print but he and Cole spoke regularly about his memories. This loss of a brother adds a tinge of sadness to the book, an imperative also that we need to talk about our lives and acknowledge the courage with which we live them. I have lost family members too and this plangency echoed with me. I was drawn also to Cole’s thoughtful examination of what migration means to people and communities, especially her parents’ experience of migration.

There were many moments during my reading of Slipstream when I thought about family and friends from Vietnam, China and India who also have shared both joyful and devastating memories of migration. These dichotomies are well illustrated in the book in its reflections on the wider themes of migration and also in stories about what Cole describes as ‘reverse’ migration, her six years spent in the north of England. Cole also challenges the idea that Australia is a new country. In her chapter, Becoming Australian, she notes:

It rankles when people speak of Australia as a new country or part of the ‘new’ world. That is a colonial construct about who ‘discovered’ the place, denying its original people their land and culture – the oldest continuous surviving culture in the world – asserting that the continent was empty. In fact, we live on a thin veneer of history, a ‘relatively short span of Australia’s British settler colonial history, a history that has barely scratched the land’s surface.’ (Cole, p 123)

The layering of wider issues beyond migration, of the split self as depicted in Cole’s reminiscing and reflecting, is a feature of the texture of this tale of contrasting worlds: the sacrifices of leaving home and family in search of a better life. Migrants leave their old homes to seek a new one in a new place. Like so many post war migrants, Cole’s family built their own home first living in a garage sized temporary homes as the permanent home took shape. Cole reflects on what this rehoming means and how home takes on a whole new meaning when sacrifice and optimism meet. She quotes the social historian Ghasan Hage who wrote that a home:

has to be a space open for opportunities and hope. Most theorizations of the home emphasize it as a shelter, but, like a mother’s lap, it is only a shelter that we use for rest before springing into action and then return to, to spring into action again. (Hage in Cole, p102)

Slipstream also explores what has changed since the post war experience of migration and why we are far less tolerant towards migration today. Early in her book, Cole poses the question of changing sympathies for migrants and refugees. While her parents’ journey in 1949 was part of one of the world’s largest mass migrations and one in seven people have now made a new home somewhere in the world, she interrogates this shifting attitude:

Why then, are we so unsympathetic to those who need a safe place? When watching as people flee wars, march towards closed borders or apply fruitlessly for economic migration, it is easy to forget just how fortunate our own families were. (Cole, p 16)

Slipstream also examines the impact of migration on family members, especially those families where some of the children were born overseas and others in the new land. Cole explores a migrant’s grief and loss and the way in which they often cling to their former cultural identity to assuage these feelings. Slipstream offers a humorous and heart-warming story of Cole’s own split between two worlds (the one of her parents in northern England and that of the sandy shores and sunburn of Sydney) while also witnessing from a young age, the struggle of her parents to ‘fit in’. She writes, ‘I want to chronicle how they plaintively memorialised the old world while staying ambitious and optimistic for the new one.’ (Cole, p20) This chronicling takes a number of forms throughout Slipstream. As well as her reflections of migration history and the ways in which other writers have pursued the topic, Cole uses anecdotes and memories to heighten the book’s atmosphere and affect. In one she recalls the way the old world entered the new Australian one via letters and parcels from Yorkshire:

One of the first things my father built on our block of land was a letter box, a neat tin affair with a sloping lid that made it look like a little tin house on top of a post, or like one of my brother’s Hornby tin train stations. The number 80 was painted clumsily on the front. It waited daily for the postman, who rode on his bike down the hill to our place, to deposit whatever thin aerogramme he had in his mail pouch that day. Sometimes he brought a parcel wrapped in canvas or parachute silk, but as time progressed these thinned out to birthdays and Christmas. (Cole p109)

Cole’s search for self in this classical memoir is engaging and offers a balance of distance and introspection. She longs for more detail about her parents’ former lives in their Yorkshire mining village and the shock of Sydney’s western suburbs in comparison. Yet she manages to draw a rich portrait of those early years:

I also want to revisit my parents’ old ‘stomping grounds’ to talk to the ghosts who populate their former lives. What might I gain from these encounters? Self-understanding, historical context, peace of mind in regards to my oddly misshapen identity, that layered self I carry about with me; Australian, British, global, one of the ‘citizens of everywhere and nowhere’. (Cole, p.20)

A feature of Cole’s approach in this important memoir is the inclusion of other views, writers and academics who have looked closely at migration and what it means for them personally and for society. The discussions of migration’s impact on individuals and communities offers perspectives, including writer George Kouvaros who wrote that migration is about a ‘dispersal of the narrative details that we use to understand the people close to us’. The book also draws on the research of historians Paula Hamilton and Kate Darian-Smith, and Hammerton and Thomson in the UK whose research focused on families such as Coles, calling them ‘Australia’s Forgotten Migrants.’

The ways in which the children of migrants feel torn between their parents’ old culture and their own new one offers reflections on the passion for travel that Cole and her peers pursued in backpacking holidays to the ‘old’ country. Cole made several such journeys to her parents’ homeland, the first a six-week journey on a ship bound for England, as a backpacker when she was still a teenager. The significance of the sea – its moodiness, the inability to hold on to it, this kind of ‘slipstream’ permeates Cole’s story and travels. She notes that it is no accident that she first travelled to England by sea – all her life she had heard stories about her family’s passage to Australia on the Empire Brent and here was her opportunity to experience their sea voyage in reverse:

Travelling by sea seems to open vast philosophical conundrums. It causes you to rethink your size and shape and mobility. It offers danger, beauty, secrets. You ponder them at dusk as the sun sinks into the ship’s churning wake and syrens call you to them.’ (Cole, p 41)

Reading about Cole’s desire to trace her parents’ footsteps around northern England – in particular, the roads and lanes and coal mines of Yorkshire – I was reminded of my own desperate longing to live the life I felt I missed out on. This desire to keep our dead relatives living through writing is well-documented by memoirists around the world. Cole writes about her journey through Yorkshire with the ghosts of her family, following them north across Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumberland to their stepping off point on the Clydeside docks of Glasgow. In similar sentiment of the longing and remembering shared by Palestinian author, Atef Abu Saif, Cole shares her yearning to keep her family and her dying brother alive and moving forward.

Cole’s travel is revelatory. She waits ‘like an animal ready to pounce’ on any new insights or stories that help her to understand her own family and their place in the world’s migrant stories. All the while, she is wishing for the conversations with her parents – more stories, more jokes or explanations – she never got to fully enjoy before both had died. It’s true that our thanks to our parents for their sacrifices often come too late. ‘Waiting for the next story and the next,’ she writes, ‘those narratives which, stitched together, make a person who they are and what they understand of themselves.’ (Cole, p 210)

The shape and structure of Slipstream is both meandering and provocative, encouraging the reader to see more than one view of the places Cole visits or where she resides, Bankstown, Liverpool, London, Melbourne, Sydney and of the people and politics she encounters. A favourite part of the memoir for me was a recall of her university days and the reforms made possible to our generation by the Whitlam Government of 1972 – 1975. Those years transformed Australia with their visionary changes, including those to migration policies and multiculturalism under the guidance of Ministers such as Al Grassby. Slipstream also captures the tyranny of memory and the ways in which we remember our families. One particular passage felt particularly poignant as the child Cole lines up for a family photo underneath a flowering jacaranda tree:

Our family home in Bankstown also retains a tyranny of memory. Now both parents are dead, my siblings and I rarely talk about the house, nor about those unsettled early years when we became Australians, in theory at least. The house might rise before us when a memory needs verification. Was it then? Where was that? Waiting for older siblings’ memories to act as the binding agent for something not quite formed. Our parents can’t be asked at all. But the dead speak through photographs and tape recordings, in a flickering family home movie of us all standing self-consciously in front of the flowering jacaranda opposite the back door, its bell flowers drifting above us like purple snow. (Cole, p.113)

Cole’s migrant parents sacrificed so much of themselves and their history for her and her siblings but their story suggests they had no regrets about leaving. Once settled in their new lives they eventually embraced Australia’s way of life, all the while retaining their quintessential Yorkshire ways and accents. Now Cole’s extended family is a multicultural one. The Cole children marries partners from Maltese, English, Irish, Austrian, Indian, and Italian backgrounds. The opportunities of work and education available in Australia in that era are well documented in Slipstream too and they convey how much countries benefit from and can support diverse communities. This is the hope and promise of migration.

CAROLINE VAN DE POL is a writer and university lecturer in media and communication. She has a PhD in creative writing and teaches writing workshops internationally. Caroline has worked as a journalist and editor and is the author of the memoir Back to Broady (Ventura 2017). She lives in regional Victoria.

February 27, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Carapace

Carapace

by Misbah Wolf

ISBN 978-1-925735-41-3

Vagabond

Reviewed by LISA COLLYER

You can imagine tracing the spiral on the white snail shell on the front cover of Misbah Wolf’s second poetry collection, Carapace to find yourself centred in a temporary house. Wolf’s scintillating and edgy collection of prose poems form individual houses with their fully justified box-shape with an entrance and an exit. Each house is named for their characteristics experienced subjectively by the poet, an experience of phenomena that transcends walls, closets, and beds, and rather how houses shape the inhabitants. In ‘COMMON PEOPLE HOUSE’ (p.21) the female residents transform into ‘witches’ (p.21) as they ‘tuck him (‘a man almost dead drunk’) in again, us in our dark robes/ muttering over his body and bringing water to his lips’ (p.21) in an alchemical reinvention of self.

Wolf opens the door on the house, and the mysteries of poetry with the use of the egalitarian form of the prose poem, a revitalised form that is on trend for its sense of breaching genre boundaries. We, the readers are invited in, to follow the inner perimeter of house. There are entry points and exit points, but this is not a linear progression, the spiral turns in on itself, in an attempt, to find itself at home, unrealised until the final poem, ‘THIS MUST BE THE PLACE HOUSE’ (p.45). But first there is a journey into strangers’ homes like in ‘HOUNDS OF LOVE HOUSE’ (p.9) where possessions are so limited, they can be ‘bundled into four garbage/ bags’ (p.9). Unlike the objective account of a home that appears on paper to be inviting, the ‘kitchen was white marble’ (p.9) the phenomenological experience is alienating ‘a middle-aged woman/ who never wanted to talk to her’ (p.9) and ‘a/ fridge stocked with food that was not hers.’ (p.9) Perhaps the symbolism of ‘white’ is the dominant racism that the POC poet suffers. The speaker’s dreams help her make sense of her rootlessness as she is transferred symbolically into a ‘tiny white poodle incessantly scratching at her bedroom door…’ Won’t anyone let me in?

This search for home is at times a plea in ‘H IS FOR’ (p.10) and conjures Gaston Bachelard’s poetics of space in the way it takes root in the sensory and experiential relationship to setting. This longing to be let in, to find a house that feels like home, is a desire to belong where the senses reign supreme, the urge to ‘run my hands through the dad’s hair’ ‘over the dirty knives on the kitchen counter, block/ out the telly with my form’ (p.10) is perhaps a need to take up space, inhabit a setting, to be seen inside as part of the furniture and therefore safe as houses.

Wolf is unapologetic in her honesty of the most intimate goings on in-house. This is what makes the collection so authentic; it doesn’t gloss over the abject nature of ablutions and sex. In ‘MRS ROBINSON’S HOUSE’ (p.25) the speaker enters a prohibited space with a tryst with a married man, hence the allusion to the film ‘The Graduate’ and theme song. The drole tone with the familiar yet unlikely excuse ‘You were married but you had an understanding with your wife’(p.25) follows the abject ‘You slipped your finger over my bloody menstrual pad which only/ amplified the sincerity of your next move’ in homage to Kristeva, the abject and desire are intermingled into the most confessional and private moment in the hunt for transcendence. And we know this, and we’ve all been there, but Wolf gives this space in the most personal of place, the home.

The sense that faraway places inhabit our beings and form our sense of self is captured in the lusty ‘JE TE VEUX HOUSE’ (p.31) where Tibet inhabits ‘The house (that) stretched like a big turd that’s been freshly shitted from a gigantic/ brick beetle (even though it)…was 9351 Km (away.)’ (p.31) The bodies are separated, not by proximity but spirit of affiliating with another country being occupied by the lover, invaded by the raider, and discarded like the two-timer is sensuously rendered ‘In the night a ribbon-like body of water called you and I realised/…there was now a ravine between us.’ (p.31) The speaker addresses the lover with the direct ‘you’ and we the reader are invited to be privy to the affair that coils to a fever pitch only to be discarded for a new temporary abode, another shell, perhaps new shelter.

The prose poem is an outlier: its form is defiant as is Queer space, an intimacy seen as genre bending. Hence, the form has taken off with Queer expression that is flammable in ‘UNDER THE PINK HOUSE’ (p.32). The poem begins ‘It was pornographic science fiction’ with the premise of speculative fiction, ‘What if?’ laying down a dare to imagine Queer space as mainstream. The speaker’s passion is whipped into a sexual frenzy that ‘lassoed me to the bed, and your pussy adopted/ the same penetrating gaze’ disrupting the male gaze for the queer gaze and the site of cunt power. The pluralism of female genitalia embodies Luce Irigaray’s book, ‘This Sex which is not One’ in its celebration of the layers and multiplicity of that which is considered ‘one’ ‘hole’ ‘empty space’.

‘In the centremost labyrinth of your labia, I unintentionally/ scryed your future and saw echoes of tall trees in gentle winds, fingers/ turning pages of burning books with images of hungry baby birds that/ would be unlikely figures of your liberation.’

The ‘L’ word is tossed around in a search for togetherness but like the search for home, it is elusive. In ‘WILD HORSES HOUSE’ (p.12) there is a violence to the coupling ‘This awkward painful screwing that will bleed/ out.’ (p.12) and is perhaps significant of the first time, or sexual violence, or just bad sex. The futility of life is expressed through allusion to Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’ where the speaker’s bleak life is reflected upon with ‘This/ cannot be it, surely’ demonstrating the restlessness of the speaker and the hope for so much more. The violence or just lack of real affection is amplified with the only tender touch to be that of ‘Kafka roaches’ soft antennae combing her face in the/ night.’ A sense of annihilation is vividly rendered with the very stark image of ‘cockroaches may survive up to a week without a/ head by just breathing through their skin’ (p.12) and we reflect on what seems the futility of everyday life.

The poem ‘THE CONSTRUCTION OF LIGHT HOUSE’ (p34) reads like an inventory of a rental account of a shared house: a bit battered like its residents but will do as a temporary space, but there is more than just ‘mustardy yellow cupboards’ ‘unpolished wood’ (p34) and ‘windows looking on to a sloping backyard’(p34): there are also ‘contrails’ (p34) on the floor, residue of a face planted, the imprint a person leaves behind on the house, and the marks left within the bodies of the experiential ‘this line/ cuts through time and flesh.’ (p34) This poem is an homage to the share house, to temporary house buddies who are everything in that sliver of time, but will not live on in your next transformation and the boy who will ‘never make it as a writer’; he too is a passing fling, like the ‘stray (cat) who wandered in one day and/ never left. You end up belonging to each other.’ (p.34) And like the temporary houses we call homes, they too are like a beacon of hope, where when the lights go out, love, lust and violence happen. Most of all Carapace is about the discarded shells and the resonance of those shelters that live on and on in our bodies, our only permanent homes.

LISA COLLYER is a poet and educator and the author of How to Order Eggs Sunny Side Up (2023)

Life Before Man Books, Gazebo Books. She was short-listed for The Dorothy Hewett Award

and was an Inspire writer-in-residence with The National Trust of W.A.

February 27, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Sevana Ohandjanian is a writer, translator and film programmer of Armenian descent, living and writing on Wallumedegal land. Her work can be found in Meanjin, Chogwa, The Suburban Review, Shabby Doll House, The Wrong Quarterly, Tincture, SBS and more. Her unpublished manuscript Black Grass was shortlisted for the 2017 Kill Your Darlings Unpublished Manuscript Prize. Find her online @ichbinsev.

Sevana Ohandjanian is a writer, translator and film programmer of Armenian descent, living and writing on Wallumedegal land. Her work can be found in Meanjin, Chogwa, The Suburban Review, Shabby Doll House, The Wrong Quarterly, Tincture, SBS and more. Her unpublished manuscript Black Grass was shortlisted for the 2017 Kill Your Darlings Unpublished Manuscript Prize. Find her online @ichbinsev.

DRIP

The drip started when I came back. Or maybe it had always been there and I just hadn’t seen it. Felt it. You’re always leaking, faulty, dispensing parts of yourself unknowingly. The drip begins and you simply continue. There’s no before or after timestamp. A faucet with the slightest leak, a midnight droplet that gathers on the showerhead and plops down with its weight, a drop in the ocean. But the ocean is a sponge and it soaks everything in. My drip is expelled from what it feeds on.

I wanted her to have become ugly. But she looks the same. Maybe I can’t see her any other way. Standing at the back of an Armenian Saturday school classroom, I watch the children clamouring to get her attention. Miss Lily! Miss Lily! Every child is a remodelling of prepubescent me, enamoured.

When Lily sees me, blood flushes my face, my breath caught. Caught like a 10-year-old being told for the first time, “You’re my best friend”; caught like a girl found out. She smiles, approaches.

She stands beside me during the principal’s announcements. Leans towards me to speak softly.

“It’s been a long time, Eva. Are you married yet?”

“No? I’m sorry. What?”

“I’m engaged.”

“Congratulations?”

“Thanks.” Her bunny rabbit teeth briefly appear when she smiles at me. “I haven’t seen you around here in a long time.”

“I was living in London for a while.”

“I know, I saw the photos on Insta. How come you’re here though? I didn’t think you kept in touch with anyone from school.”

“I’m just doing a favour for one of mum’s friends. They said they needed another teacher.”

“Yeah, Ani had to quit. Her baby’s due in a couple of months.”

“Sure. Right. Then I’m here to replace Ani.”

“Are you back in the suburbs then? With your mum?”

“Yeah. You know, trying to take care of her.”

“And you’re not engaged?”

“No.”

“In a relationship?”

“Nope.”

“Dating any boys?”

“That’s also a no.”

I had arrived airtight, the excommunicated package returned to sender, not a leak to stain the exterior of me. But questions kick my sides into dents. I’m devoid of meaning in this place. Yet I can’t resist the urge to ask.

“So, who are you marrying?”

“You know him actually! He was a year above us–”

The principal calls to me: “Eva, we’re ready to start, let me show you where your classroom is.”

I’m tasked with overlooking the work of three pre-teen girls in the back of a classroom, minimal responsibility while an experienced teacher manages older students emanating static exam preparation energy. The room coils with summer heat, brick-encased sweat, blinding yellow sun glow. The girls kick their feet and rapid-fire questions. We’ve never seen you before Miss, where are you from Miss, how come we don’t know you Miss, did you come to this school too when you were learning Armenian, Miss?

The heat brings the warm sweat drip. Frizzed ends of hair damp at the nape, elbow crease droplet a wet snake. Soles melting into asphalt, fire hits hot, until it swallows feet and turns into statue grey stone. I’m pebble-footed, fog-headed, standing in front of these children, teaching them words I’d forgotten.

Afterwards in the parking lot, my car idles as I avoid the touch of molten metal fixtures against bare flesh. An atomic sizzle between my fingertips and steering wheel, my skin branding and moulding itself to machine. Gathering itself back together, water to jelly to rock. Baby hairs dance around in air conditioning vent choreography, and I see her, striding gracefully towards an electric blue car. Nissan Skyline, Fast & The Furious fantasy for the high school dream boys with fade cuts and bubbling aggression.

The car pulls out, drives by me.

—

There’s nothing to do here besides walk through grass smoked into hay, and stare into people’s backyards. Jumping back when a dog comes barking up a driveway, its snout snarling through the gate. Hearing trucks barrelling down the main highway. Driving for the sake of hearing an album through car speakers, to give it motion. Other peoples’ houses and time-haunted shops, the only places to go.

Western Sydney suburban ennui cushioning my red skin, my squinting eyes, dripping into my vision when shut, all squiggly flashing lines. I can’t leave it. I’ve taken it with me to every city I’ve lived in. An empty street is home even if it’s hollow.

The shopping village that still holds the dirty yellow glow of too-low lighting and too-dark corners. Butcher meat stink pulses, bakery loaves expand in their racks, the newsagency ceiling fan whirrs dust over untouched magazine covers.

In the unnaturally bright grocers, I’m slumped over a shopping trolley in the produce section, eyeing off the fruit, willing light to disperse me amongst the blood red apples.

A hand on my shoulder brings me back, collecting and rearranging me. Of course she’s here. Actualised from my mind where she’s found residence since I saw her in the classroom a week ago.

Carrying a shopping basket like a handbag in the crook of her elbow, she is what activewear ads convince me I could be: slimmer, fitter, happier, wearing leggings to the shops after the gym session. She exudes a glow that highlights my dullness.

She’s talking to me but I’m still the pillow crease from the morning, blue light shining in my face. My finger surfing over my phone screen at speed with a tender touch, cautious voyeurism. She is amalgamating before my eyes: crucifixes, gold and silver, shiny helium anniversary balloons, lace and chiffon. His pink nose filtered to snowy white, tight shining faces dripped together and melted, pushed in so close as if to pull apart would tear the conjoined sinew.

She’s inviting me to a party in her backyard. As I agree, I’m thinking of excuses not to go.

—

I have been here before or I haven’t. Down cul de sacs lined with palms, into townhouse driveways signposted with identical beige postboxes. Two years of sucking in smog and suffocating sound is compacted into the back of my mind, an already othered memory.

The backyard grips me by the neck, thrusts me face-first into nostalgia. Plastic white chair-seated men, hookah pipe passes, women in constant motion to buckle a trestle table with food.

This is every backyard from high school house parties when we’d stand around, flip phones grasped like prizes, being fed alcohol by parents who didn’t care for local laws. The so-small world looking remarkably wide in a fenced-in, half-concrete yard.

He’s not beside Lily, he’s amongst the white chair men. Legs spread, possessive eyes, shisha in hand. Déjà vu so strong I’m convinced he hasn’t moved an inch since 2004. His nose the same ruddy pink as that hot humid day, when I had squirted my water bottle at him while we waited to climb into the school bus. The second last day of school. Giggling to coax male fury off the ledge when he said, “I’ll get you for that”.

My skin pink the next day walking down the highway home, water dripping from hair and hem timed with shivers. Truck drivers honking at my now transparent cotton sports uniform. My ears echoing the smack of litre on litre pouring over my head. Ice cold shivers from frozen water bottles, then lukewarm waterfalls from orange juice-stained canisters. His deep laugh slicing through the cascade.

Now, a bead of sweat tickles down my back. I plant myself in a corner, let my sandaled feet brush grass. Sinking myself in deep, deep enough to become a nutrient for the soil, enough that I might fertilise and dissolve. As I watch him watch her, I know when she is watching me.

There’s small talk and a barbecue, drinks and cigarettes, heels poking holes into garden grass. My eye can’t leave the white chair corner, even while three ex-classmates come to interrogate me. They’re trying to strike gossip gold to take home tonight. Lily joins and stands across from me, that beaming warmth enveloping.

“Having fun?” she interrupts the conversation to ask me.

“Yeah, thanks for inviting me”.

“Of course. You should come to the wedding too, maybe you can meet a nice Armenian guy, make your mum proud.”

She laughs, a delicate thing. How is it so intimate yet the furthest thing from close. A reminder that the space is so vast between us, it is practically solid.

I move closer to Lily as someone takes a drum out, slapping a rhythm that draws people into hand-held circles. An unrushed dance, hands grasped with strangers, two steps forward and one back. A movement that should be in my feet already, a genetic predetermination. She’s the centre point of it, like a fountain timed to music, her hair splaying out, her body spinning, her arms elegantly shaping in the air. When our eyes meet briefly, my smile is second nature. I feel stripped down, heart stuck in throat. Melted as if to expose the centre of myself.

She is the person they sing about in the song, and I’m the person who dances to it.

—

Heat has a personality of its own. It demands. Craves the attention of all your senses. Heat sticks in your throat, it inflates humid into the lungs, it sinks into pores and forces your insides out.

I stand under the lazy ceiling fan in the classroom, in another lesson that has blurred into the weeks preceding it. Saturday mornings of burning sunlight and irritable children desperate to be elsewhere. Lily in the morning gathering, hearing her voice ring out an octave higher than the students during the national anthem. Afternoons of parking lot small talk, disappearing into cars and separate worlds.

The fabric on my skin is becoming one with me. Cotton tendrils sneak into microscopic pores, latching onto cells and choke-holding them until shirt is body and body is shirt. I want to flatpack myself. Ship myself back across oceans, until all that falls on me are snowflakes turning water, until my hair is drenched and my breath is tangible fog.

Once the bell has rung, I turn off the lights and stand in empty midday darkness. The stale air, the flecks of dust, the beige brownness of it all. I was never afforded silence in this space. Even now, I can feel the squeeze of time against me. Siren songing me into the past, into a safety that regresses and reidentifies.

Lily is sitting on a bench outside the school gates when I approach her. A backpack sat at her feet, she types speedily on her phone and doesn’t look up until I’m sat beside her.

“Did you have a good day today?” she asks, looking up from her phone, eyes directly on me.

“Same same really. I don’t know if I’m actually helping these kids learn anything.”

“I’m sure you are. They’re good kids.”

“Do you need a ride?”

“No, Sako will be here soon. We’re going to get a late lunch.”

The sun is bearing down on my unprotected face, marking its spot red. The drip is puddling around me, forming a lake on which I’m drifting. When was the last time we sat so close.

Back when she was ankle socks and me regular-length folded and pushed down. Back of the school bus giggles, we’d gotten lucky that the older kids let us sit there. We felt older than our 12 years with the privilege of hiding in the corner, huddled close. Grease of morning margarine sandwiches still on our lips, discarded foil crunching beneath our feet. She told me her underwear was black. Everything I wore underneath was a virginal white. Show don’t tell, we lifted skirts, reached across and under as if to confirm that the differences between us ended at the colour of our underwear. A Year 10 girl turned around to look at us and we knew somehow this wasn’t allowed.

We’re in a cone of cool silence now. The heat is away, the drip has stopped. Like an ice cube down the back of the shirt, there is something kinetic here. Something that wants to burst out of my pores and slide over the seat. Where are the lines drawn on our bodies now, that didn’t exist then.

“Do you remember those bus rides we’d have to take here every day?” My voice is not my own. It’s liquid turned sound, moved its way from stomach to trachea and out.

“They took so long! How did we even do it. They were so boring.”

“I liked them.” Me and you. Shoulder to shoulder, arm to arm, leg to leg, knee to knee. Gossip and giggles, a level playing field.

“Sako used to ride on that bus too, you know? He said he had a crush on me even back then”. Glimmering eyes, bunny teeth, the child peeking out of the adult. “But he never did anything about it.”

A car honks and the sun hits my eyes, firing down my face. She walks away, a gentle wave, a slide in and shut door.

I drip away in a sun melt. Until I can fall from the bench in droplets, slink my way down the gutter, foist myself into the drains. Let myself be carried to the dam, rushed alongside the drips of others, funnelled into drains mapping our suburban yellow underground. Until I slip down her tap, into her glass, and am entirely consumed.

February 23, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

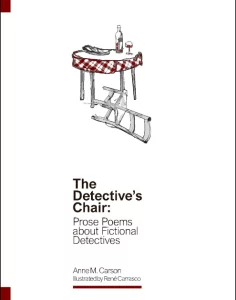

The Detective’s Chair

The Detective’s Chair

by Anne M. Carson

LiquidAmber Press

ISBN 9780645044980

Reviewed by JENNIFER COMPTON

Poetry has many pleasures, and, as quite a few of us might suspect, an almost equal share of pains. But every so often, every so often, a book comes along that panders to my desire to loll about reading a detective novel, one hand dipping into the box of chocs and riffling the paper cups to come upon an orange cream, which is my favourite. I am aware, out of the corner of my eye, of the literature outlining the comfort of a rules-based, escapist genre, where the murder victim is rarely, if ever, someone you have come to like. But it wasn’t until I read Carson’s “Reflections on writing The Detective’s Chair” at the back of this book, that I twigged that what I am really liking is the almost preternatural intuition of the crime solvers.

‘The insight came to me while I was sitting in my favourite red, upholstered chair with my legs curled beneath, a pot of Madura tea to hand: my favourite fictional detectives solve crimes similar to how I write poems. They are essentially creative people – and solving crimes is an essentially creative act.’

Then I surrendered, willy nilly, to my baser nature and riffled through the pages to check out my favourites. My orange creams. Miss Jane Marple of St Mary Mead. Who, whilst weeding her herbaceous borders, looks boldly into the dark heart of wickedness. And Detective Chief-Inspector Adam Dalgleish, of Scotland Yard, who resorts to writing poetry – your actual slim volumes – between cadavers. Although he is appropriately self-deprecating. And, of course, Inspector Kurt Wallander in Ystad, Sweden, shambling around in a welter of piles of dirty laundry and unmet obligations –

‘ … desperate for a few motionless

moments to let his thoughts run unfettered. A niggle, just out of

reach, an uneasy ache he knows holds vital clues. Something

someone said or didn’t say–elusive since the first murder. If only he

could sit quietly, listen long and open enough for it to unfurl, maybe

it would crack the case wide open.’ (p65).

Now this poem is called “Uneasy ache” but I first came upon it when it was called “The Detective’s Chair” – a singeleton, an outrider, the harbinger of plenty – and I was very much struck with the intersection of popular culture and poetry. I may have become forceful in my desire for more. I remember discussing the difficulties of tackling Commissario Guido Brunetti, because he is happy, as Anne and I took our keepcup coffees down to Carrum beach during the longeurs of Covid lockdown.

‘There is nothing noir about Guido Brunetti. Noir needs ground of

loneliness, food of melancholy. Crime-solving gets him down from

time to time but he is reflective, philosophical, dives into Herodotus

for distance. On the case, he is professional, meticulous; his nose

and native cunning winkle clues out. He doesn’t come home from

violence to empty taunting rooms, to the siren song of ghosts -’ (p11).

However, I am not meaning to imply that this is not poetry of the most serious intent and of the highest order. It understands its place within the oeuvre, it invokes tried and true devices, it succeeds as poetry. But, because it is entangled with another genre, there is a kind of slippage, and also of homage. Carson has laid down solid rules for herself, in the spirit of the genre she has playfully appropriated. Each take on a detective is a fourteen line prose poem. I suppose you could almost aver – sonnets of the prose poem ilk.

Quickly, I must mention, one of the delights of this delightful book, produced by the indefatigable Liquidamber Press, are the quirky illustrations by René Carrasco, which seem to glow with nostalgia for a simpler age. As does the dedication to Dorothy Porter for her heroic ploy to get poetry out of the bottom shelves at the back of the book shop into the display stands at the front with The Monkey’s Mask. That worked well for her, but that was 1994. However it was a bold move, and it made its mark.

‘Jill’s too busy courting trouble on the mean streets for

time in a chair, feet-up. When she grabs moments from the

malestrom, it’s her backyard fishpond which settles her. She

becomes mesmerised by the gold swirl and swish beneath, the

glimpse of a tail, hypnotic lure of dreamy movement and then the

shape of an idea emerges from the depths, leading to her next step.’ (p7).

Please do buy this book for a childhood friend or a brother-in-law or a great-aunt who isn’t quite sure they like poetry much, but who you know devours detective fiction. And then watch them forget that it is poetry they are reading, as they flick back and forth checking out whether Carson has included their particular favourites, and also to get ideas for authors new to them to chase up. And then watch them becoming absorbed and reflective as the poetry does its work.

JENNIFER COMPTON is a poet and playwright who also writes prose. She lives in Melbourne on unceded Boon Wurrung Country. Recent Work Press published her 11th book of poetry the moment, taken in 2021.

February 9, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Raised in Whyalla and now residing in Adelaide, Justine Vlachoulis studies literature and film at The University of South Australia. She endeavors to explore the stigmas and stereotypes surrounding the contemporary sex industry, while also sifting through the past to discover and retell the comical and thrilling stories of her Greek migrant family. When not rambling to anyone who will listen as to why Anton Chekov and Thomas Hardy are her literary heroes, she enjoys baking, photography, and short walks.

Raised in Whyalla and now residing in Adelaide, Justine Vlachoulis studies literature and film at The University of South Australia. She endeavors to explore the stigmas and stereotypes surrounding the contemporary sex industry, while also sifting through the past to discover and retell the comical and thrilling stories of her Greek migrant family. When not rambling to anyone who will listen as to why Anton Chekov and Thomas Hardy are her literary heroes, she enjoys baking, photography, and short walks.

I Found You in the Supermarket

I’m in a supermarket trying to find you. This was one of the last places I saw you. I drift past pyramids of orange and avocado and stare across at shiny packets of red meat. My legs carry me to a loaf of Wonder White bread. All the voices start singing in my head. All the voices wishing you weren’t dead…

‘Agapia Mou, my love,’ she whispered.

In the village, Agía Eiríni, Saint Irene, in a crumbling house, alone in the dark, a mother held her baby and prayed.

The baby still wrapped in it’s amniotic sac, a caul of hunger and want, was doomed by the poverty WWII brought as German and Italian soldiers filled their bellies while waiting for war.

The next morning the mother filled threaded bags with olives from the family grove. Beneath the shade of a nearby tree, baby George lay asleep.

Mother Adrian wasn’t lean and tall like the women from Athens or Thessaloniki. Rather she had wide hips and a beaming mouth that stretched across her square jaw. Under the beating sun two rows of perfect white teeth flashed bright, as sweat seeped its way into her short black hair. It never aged white or grey.

After George, she gave birth to another boy, but before them, there were seven more. The first son Andrew died, and when three girls followed, Olga, Ketie, and Reubina, Mother Adrian and Father Gerasimos despaired. Who was going to work? But five babies came along, and they were christened Danny, Andrew, Thomas, George and Sammi. All the children were blessed with mesmerizing hazel eyes, but from their heads grew unruly tangles of dark brown frizz. George’s hair grew to be closer to black then it was brown. The day after each birth, Mother Adrian laboured in the groves wearing her thin floral dress and brown leather sandals.

There was a year when all the Vlachoulis children went to school at the same time. They’d leave in the morning and return in the afternoon and they’d each wait their turn to use the household pencil to do their homework.

In the mornings, the three youngest, Thomas, George, and Sammi would sprint through blades of grass to suckle on hard rough udders and in the evenings steal fruit and scamper home to offer their treasures.

The Vlachoulis house was small, so the boys shared a bed, and so did the girls. They lived in an area of Agía Eiríni called Vlahoulata, and Vlahoulata was small, so the village rooster’s song carried far enough for all to hear. Thomas, George and Sammi called the village rooster ‘rooster clock’.

One morning, when the sun hadn’t yet stretched its rays, and the world was still painted in pastel hues of purple and blue, tiny pairs of feet crept through Agía Eiríni’s empty streets. Three small figures darted from one house to the next, bare little tummies holding their breaths. The boys were all the village had seen since their Father Gerasimos had stumbled around drunk a few hours earlier.

Asleep inside the shade of a wooden hut, was their rooster clock. His scraggy feathers and clawed feet were whisked away by a child’s sturdy hands. With heads held high Thomas, George, and Sammi walked in a line, and George held rooster clock clamped to his chest.

They went to a clearing, and the sun rose higher, casting olive tones on their skin.

George gave the orders.

‘Thomas hold the neck.’

Thomas secured the neck.

‘Sammi, feet.’

Sammi secured the feet.

Then George swung an axe he’d stolen from Father Gerasimos over his head and brought it down through the bird’s stomach. The boys watched with gleaming teeth as rooster clock’s insides showed. They stroked tentative fingers over dripping red feathers and then dug determined thumbs into slimy pale guts, each of them searching for the round prize with ticking hands.

The minutes dragged on, but eventually, each boy had to stand back.

Sammi frowned, and pointed a gunky finger at the bird, ‘Where is it?’

Thomas shook his head, ‘I don’t know.’

They both looked up to George, who stood with the axe over his shoulder, but he looked back at them, just as confused.

With a shrug, he said, ‘I don’t know where the clock is. Maybe the head?’