May 12, 2025 / Nathan Morrow / 0 Comments

Judith Beveridge is the author of seven previous collections of poetry, most recently Sun Music: New and Selected Poems, which won the 2019 Prime Minister’s Prize for Poetry. Many of her books have won or been shortlisted for major prizes, and her poems widely studied in schools and universities. She taught poetry at the University of Sydney from 2003-2018 and was poetry editor of Meanjin 2005-2016. She is a recipient of the Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal and the Christopher Brennan Award for lifetime achievement. Her latest collection is Tintinnabulum (Giramondo, 2024).

Judith Beveridge is the author of seven previous collections of poetry, most recently Sun Music: New and Selected Poems, which won the 2019 Prime Minister’s Prize for Poetry. Many of her books have won or been shortlisted for major prizes, and her poems widely studied in schools and universities. She taught poetry at the University of Sydney from 2003-2018 and was poetry editor of Meanjin 2005-2016. She is a recipient of the Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal and the Christopher Brennan Award for lifetime achievement. Her latest collection is Tintinnabulum (Giramondo, 2024).

Listening to Cicadas

Thousands of soda chargers detonating simultaneously

at the one party

*

The aural equivalent of the smell of cheese fermented

in the stomach of a slaughtered goat

*

The aural equivalent of downing eight glasses

of caffeinated alcohol

*

Temperature: the cicada’s sound-editing software

*

At noon, treefuls of noise: jarring, blurred, magnified—

sound being pixelated

*

The audio equivalent of flash photography and strobe lighting

hitting disco balls and mirror walls

*

The sound of cellophane being crumpled in the hands

of sixteen thousand four-year olds

*

The aural equivalent of platform shoes

*

The aural equivalent of skinny jeans

*

All the accumulated cases of tinnitus suffered

by fans of Motörhead and Pearl Jam

*

Microphone feedback overlaid with the robotic fluctuations

of acid trance music

*

The stultifying equivalent of listening to the full chemical name

for the human protein titin which consists of 189,819 letters

and takes three-and-a-half hours to pronounce

*

The aural equivalent of garish chain jewellery

*

A feeling as if your ear drums had expanded into the percussing surfaces

of fifty-nine metallic wobble boards

*

The aural equivalent of ant juice

*

Days of summer: a sonic treadwheel

Peppertree Bay

It’s lovely to linger here along the dock,

to watch stingrays glide among the pylons,

to linger here and see the slanted ease

of yachts, to hear their keels lisp, to see

wisps of spray swirl up, to linger along

the shore and see rowers round their oars

in strict rapport with calls of a cox,

to watch the light shoal and the wash scroll,

and wade in shallows like a pale-legged

bird, sand churning lightly in the waves,

terns flying above the peridot green

where water deepens, to watch dogs

on sniffing duty scribble their noses over

pee-encoded messages, and see a child

make bucket sandcastles tasselled

with seaweed, a row of fez hats, and

walk near rocks, back to the jetty where

fishermen cast out with a nylon swish,

hoping no line will languish, no hook

snag under rock, to watch jellyfish rise

to the bay’s surface like scuba divers’

bubbles, pylons chunky with oyster shells

where a little bird twitters chincherinchee

chincherinchee from its nest under the slats,

to feel that the hours have the rocking

emptiness of a long canoe, so I can relax

and feel grateful for the confederacies

of luck and circumstance that bring

me here because today I might spy

a seahorse drifting in the seagrass

with the upright stance of a treble clef,

or spot the stately flight of black cockatoos,

their cries like the squeaking hinges

of an oak door closing in a drafty church,

to walk near the celadon pale shallows

again where I’ll feel my thoughts drift

on an undertow into an expanse where

they almost disappear, and give thanks

again to the profluent music of the waves,

and for all the ways that light exalts

the world, for my eyes and brain changing

wavelengths into colour, the pearly

pinks of the shells, the periwinkles’ indigo

and mauve, the sky’s methylene blue.

These poems are published in Tintinnabulum (Giramondo,2024)

May 12, 2025 / mascara / 0 Comments

Alison J Barton is a Wiradjuri poet based in Melbourne. Themes of race relations, Aboriginal-Australian history, colonisation, gender and psychoanalytic theory are central to her poetry. She was the inaugural winner of the Cambridge University First Nations Writer-in-Residence Fellowship and received a Varuna Mascara Residency. Her debut collection, Not Telling is published by Puncher and Wattmann. www.alisonjbarton.com / Instagram @alison_j_barton

Alison J Barton is a Wiradjuri poet based in Melbourne. Themes of race relations, Aboriginal-Australian history, colonisation, gender and psychoanalytic theory are central to her poetry. She was the inaugural winner of the Cambridge University First Nations Writer-in-Residence Fellowship and received a Varuna Mascara Residency. Her debut collection, Not Telling is published by Puncher and Wattmann. www.alisonjbarton.com / Instagram @alison_j_barton

Mirror

|

my mother was a bear that couldn’t walk itself |

| her reside a sulking weight I trailed |

|

|

grief hauled from under the volume of her |

| my reflection, an infancy of sound-gathering |

|

|

|

|

like an instrument archiving its vibrations |

| I stored language for both of us |

|

|

tooled it to fill her gaps |

| we bore the cacophony as one |

|

|

|

|

she arranged its tenors |

| woefully concrete, stalkingly anchored |

|

|

the shape of me lined with benevolent deceit |

| her indebted angel-monster |

|

|

at the door she would cant, hoping it might open |

| night would plummet and I would flinch |

|

|

breathe in what had been committed |

| abandoning her in the light |

|

|

words formed and stuck to the back of my throat |

| when I measured her |

|

|

I got an elliptical question that reinforced our wounds |

| petrified its answerer |

|

|

steeped into the matter of things |

| staining the passage |

|

|

some are lost learning to speak |

| some have voices that shake walls |

|

|

fill quiet rooms |

| but the reprise, the inverted translation |

|

|

desecrated us together |

|

|

| we needed to finish like this |

|

|

with an aching acid chest |

| marched to an absolute |

|

|

now I am emptying my mother |

August 24, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

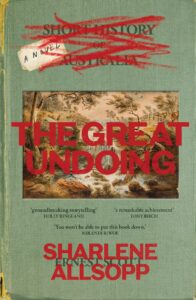

The Great Undoing

The Great Undoing

by Sharlene Allsopp

Ultimo Press

ISBN: 9781761151668

Reviewed by DEBORAH PIKE

Sharlene Allsopp’s debut novel, The Great Undoing, has a great cover that undoes history with a red crayon. Ernest Scott’s A Short History of Australia (1916) is struck out and bold typeface declares an angry and urgent call for a different version to be told. As Allsopp writes, ‘After all, only the winners write history.’ The ‘story stealers’ (1) have already written theirs, clearly, the time is ripe for a re-write.

I looked up Scott’s book, with some curiosity, to find virtually no information except advertising from antique bookshops via eBay. And now I am assailed by emails and popups, recommending Scott’s volume for purchase. But how long can these versions of history last, I wonder?

As more and more First Nations writers confront questions of representation, voice, colonisation and sovereignty, previous stories and histories of Australia will need to be thrown into question. History, it seems, is being rewritten by First Nations authors like Sharlene Allsopp, Claire G Coleman, and Alexis Wright – via fiction. Fiction has become the space for dismantling empire and for writing and rewriting history into an imaginary place or into a speculative future.

The Great Undoing is set some time, decades ahead, where the world is run by a technology called BloodTalk. Allsopp writes, ‘Everything that we are is stored in our body’ (17). Initially an immunity tool, it is soon used to track people and their locations as well as their bank accounts; it becomes a form of border control.

But the future is not all bleak, certain things are being rectified: Australia has its first Indigenous Prime Minister, ‘Ruby Walker’ who ‘enacts the Truth Telling Policies’ (34). Scarlet, an Australian refugee is tasked with the job of updating the archives and going through curricula to make sure that these are more historically balanced and that more voices are heard, presumably in a way that includes and details Indigenous stories, names and languages.

The novel flashes back and forth from Then to Now. While Scarlett is working in London, she forms a passionate relationship with a rock musician, Dylan. But there is a widespread mass blackout and a breakdown in communications. Everything is in chaos and borders are shut. Scarlet then meets David and they both travel, seemingly illicitly, across the globe to return to Australia, each for a different reason. Scarlet resorts to paper and pen to recount her experience of her ‘great undoing.’ All she has to write on is a copy of Scott’s A History.

But what is Scarlet undone by? Is it the great global technological disaster itself? Or Empire that stripped her of her story? Or is she ‘undoing’ Empire through her truth-telling work? She writes, ‘My father’ – a Bundjalung man – ’was my great undoing’ (25). Is his racial identity the source of her undoing? Or, later, we might ask, is she ‘being undone,’ in a steamy way – as she narrates her romantic encounters with poetic, scintillating prose: ‘[h]e was undoing. I was undoing. And, right then, right now’(67)?

Allsopp suggests that Scarlet’s undoing lies in all of these things, but ultimately, however, it is the undoing of identity, the pursuit of it, that sweeps the story along; the book is a meditation on both the complexity of identity and the nature of textuality – and their interwoven relationship.

In parts, the novel reads like a response to Wiradjuri author, Stan Grant’s brilliant, (if somewhat controversial) essay On Identity (2019). In his book-length essay, Grant argues against the limiting categories of identity – ‘Identity does not liberate, it binds,’(43) explaining that ‘[t]hat’s the problem with identity boxes: they are not big enough to hold love’ (19). He Writes:

If I mark yes on that identity box, then that is who I am; definitively, there is no ambiguity. I will have made a choice that colour, race, culture, whatever these things are… (25)

The result is that by ticking that box, he denies the other parts of his identity which do not fit into that box, ‘we participate in an infinity of worlds’(24), says Grant, citing Alberto Melucci, which such boxes cannot possibly contain. In a similar vein, Allsopp writes:

There have always been tiny, neat boxes to tick. Nationality Box, ethnicity box, gender box, religion box. If you tick or cross you are contained within that box. (195)

Grant attributes his influences to many writers of all colours and persuasions, insisting that many writers are Aboriginal (48), even if their genetic code would tell you otherwise, because (quoting Edouard Glissant),‘“you can be yourself and the other”’ (43) and this is what literature allows us to do. . Allsopp is also interested in showing her indebtedness, her connectedness, to a wide range of writers such as David Malouf, Rebecca Giggs, Claire G Coleman, Christos Tsiolkas and, even J. R. R. Tolkien, among others, all of whom she refers to in her book and occasionally quotes.

Arguably, however, in its attempt to reclaim Indigenous language, storytelling and identity, Allsopp’s main literary influence is that of Tara June Which and her novel The Yield, which Allsopp explicitly mentions. This is because, for Allsopp, as for Winch, language is crucial:

Language isn’t just a tool to share information or to record history. Expressed thought is powerful. It declares truths that are, and truths that are not-yet. Language breathes power into discourses of liberation AND oppression, both creating and destroying futures. (105)

Since language shapes our perception of truth, or ‘frames’ it as Scarlet tells us, it is directly linked to history, and to her job of setting it right. This is a challenge when so many Indigenous languages have been lost. In an insightful (and amusing) discussion of the power of language, Scarlet warns us that much language is used and has been used mistakenly, to wield forms of control, however unconsciously in so many ways: ‘Our language frames us all with penis-envy,’ but when considering its marvellous capacities, ‘It should be vagina-envy, baby.’

Truth telling is also central to the novel’s concerns. But this is not straightforward, ‘When a nation is built on a lie, how can any version of its history be true?’ (119). Allsopp is deeply interested in how truth can be conveyed through narrative, even hinting that there lies the possibility for multiple and perhaps even conflicting ‘truths.’

The Great Undoing examines the ways that narrative structures our perception of both cultural artifacts and the world around us. It exposes the rotten imperial core of major museums and institutions, and gloriously imagines, however briefly, how all this might be remedied. The novel is interspersed with historical tracts and extracts; it is highly experimental fiction, and robustly formally inventive. It is in some ways a narratological compendium, exploring different forms of textuality – in a bid, perhaps, to showcase the breathtaking heterogeneity of various versions of ‘truth’ and history.

In terms of style, the writing is refreshing, bracing and often affecting. Allsopp combines high literary elements with aspects thriller and romance. This genre-bending attests to the possibilities of narrative – and to the difficulty of containing or accommodating certain stories and fractured histories. It could have been the limitations of this reviewer, but at times, I found The Great Undoing difficult to follow.

Despite this reservation, The Great Undoing is exciting reading and it is a pleasure to encounter fiction that is so ambitious, conceptually intellectual, and yet at the same time, also thoroughly immersive. This is an important book.

The novel’s sense of urgency is compelling:

But what if no one tells our stories? What if there are no records left? Can they live on if they only exist in our memories? What if everything I have ever done, every truth I have ever retold, is erased? (169)

Allsopp wants to right the wrongs of the past, reclaim memory, unravel the mystery of identity, throw a tin of paint on the face of history, nudge to possibility – convey the complexity of all these things – as well as give us a rollicking good adventure. Who can ask for more?

Citations

S. Allsopp. The Great Undoing. Sydney: Ultimo Press, 2024.

S. Grant. On Identity. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2019.

DEBORAH PIKE is a writer and academic based in Sydney and an associate professor of English Literature at the University of Notre Dame, Sydney. Her books include The Subversive Art of Zelda Fitzgerald, which was shortlisted for the AUHE award in literary criticism. The Players, her debut novel is now out with Fremantle Press.

August 21, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

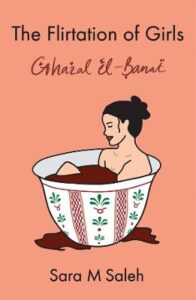

The Flirtation of Girls / Ghazal el-Banat

The Flirtation of Girls / Ghazal el-Banat

Sara M Saleh

UQP 2023

Reviewed by KATIE HANSORD

How to begin to do justice to reviewing a book of poetry this important, this powerful, and in this moment? If I were to recommend one book to people this year, it would be this. And it has been. I have told everyone I know.

As Edward Said has written, for Palestinians, “… they could never be fit into the grand vision…Zionism attempted first to minimize, then to eliminate, and finally, all else failing, to subjugate the natives.” (Said, 85). Sara M. Saleh is a powerful award winning writer, human rights lawyer, poet, “the daughter of Palestinian, Lebanese, and Egyptian migrants…based on Bidgigal land” (n pag). Saleh’s writing, reminds us again of Said’s point, her Instagram bio adding to this impressive list of occupations that she is an ‘agent of chaos’ (according to the ‘Israeli’ ambassador). Whatever kind of order would seek to eliminate any of us, I believe requires our opposition, and in its limited view, chaos, if that means the very existence of life-affirming exceptions to its brutal “vision”.

I think firstly though, maybe we must return to the question of what poetry is, because really poetry is a part of everybody, it is for everybody, and it holds such incredible power to inspire new worlds of creativity and imagination. A portal to something beyond that sits already within us. Still, I so often see people feel intimidated, or dismissive, and / or put off by it. And when I say everybody should read this beautiful book of Sara M Saleh’s incredible debut collection of poetry, I truly mean it. Everybody should have it read to them if not, should have the chance to love it and feel its love. I have easily fallen in love with this little book, from its warm peachy-coloured cover and beautiful woman bathing calmly in a teacup, right to its final page. I already want to read it again.

Last night, one of my teenage sons came into my bedroom to chat, and we got onto the subject of poetry because he knows it interests me. I said that I felt poetry was like undiluted cordial in comparison to say a novel; much more intense. “Nobody drinks undiluted cordial you maniac!’ he said, and we were laughing. I concede that I didn’t really think this metaphor through… then I said, perhaps it’s a bit like like how people feel astrology is somehow ‘fake’ somehow a lie or trick, not scientific, but either way it clearly offers us a way in to understanding and speaking and thinking about our own growth and our inner and outer experiences, poetry can do that too in a connected way through someone else’s experiences. Then he said he finds ‘themes’ as a concept the least appealing of the trilogy of plot, character, and themes, the expected elements in a story, and themes are the all of poetry it seems. I say there are many stories and characters in poetry anyway…and so he allows me to read him one poem, from this book.

I choose the final one, ‘Love Poem to Consciousness’ (‘A love poem?’ he looks quite wary. ‘Yes’, I smile, ‘but don’t worry – it’s to consciousness’) …he nods and I read:

I have dreamt of Jenin and her groves,

the figs and orchards, almonds and apricots,

the olives that ripen and ricochet between fingers.

I have wedged and waded my palms

through the soil, marinating in its wetness

the rivers of olive oil spouting even in drought.

I have grazed the Central Highlands of al-Khalil

where the ravines roll and rise,

the terracotta terraces kiss the vineyards,

dark grape hyacinths panting,

the cicadas’ wings glimmering like broken glass.

I have tracked down the oldest soap

factory in Nablus, one of two remaining,

a rush of milky rivers, baches of bars froth

into a foamy afternoon.

I have stepped onto the cobblestones

of al-Naserah, of prophecies and freshwater

spring, plumes of sacrament smoke

Strangle the indigo dusk.

I have gazed at the crystalline waters of Akka,

Felt the sting of salt puffy on my

lips, where I drank the undulating

ocean, and it drank me back.

…

I know this now, my being contracts and expands

with the land, boundless.

I know this, too: If ancestral homeland

gets me killed someday,

I’ll die like our trees, standing up.

(100)

My son does enjoy this poem – how could anybody not? It is clearly bursting with magic (perhaps another name for love, or life) after all. The final lines conjure for him the image of a pirate he had heard of, shot down, but still standing upright somehow, in defiance even of gravity itself.

The next day I woke to randomly discover a snippet of an interview by Kate Bush, an old interview from Irish television and her words struck me: “Most of my other inspiration comes from people, people are full of poetry you know, everything they say. Maybe the way they say it has its magic, all sparkly. And people are always saying things that inspire me. I mean, people are just full of wonderful things.” (Kate Bush, 25 March 1973, interviewed by Gay Byrne on the late late show.)

It resonated so heart-breakingly, with an image I had shared months ago, written much more recently this year, it was pink text on a paler pink-coloured background that was unattributed. It read:

“They’re killing poets, and not just the ones we know about.

The children who told the best jokes, the grandmothers with the funniest nonsense songs, the fathers with the turn of phrase to break your heart.

The archives replete with the words of the ancestors, now in ash.

Thousands of stories lost to the ether.

They’re killing the storytellers. And they’re doing it on purpose.”

What a thing for a heart to have to hear…

Stories connect our hearts and we know that Sara M Saleh is a brilliant storyteller, as well as a poet. Her novel Songs for the Dead and the Living was amazingly also published in 2023, in a prolific burst of gifts, the same year as The Flirtation of Girls, which is no exception, full of story, and characters, and yes, themes too.

Her use of words to convey all of these is so skilful and creative and brilliantly done, I am not sure how to show it. In the poem ‘Reading Darwish at Qalandia Checkpoint’ just this one tiny section alone demonstrates her incredible talent and wit and power as a writer:

Police investigation still pending.

The evidence – REDACTED

His rights – REDACTED

His childhood – REDACTED

(20)

There is a story here, and it is one of negation and terrible harm. A character too. But what does it mean to speak this? To show us, in the very struck out words, what has been redacted and to tell us yes, in all caps, yes – it very much has been? It somehow undoes a part of this harm, undoes its very future, as it unveils a part of what has been intentionally taken, hidden, suppressed, and it shows us how we might be able to witness and then speak back to that. Reimagine the very existence of an imperialist colonising violence… A childhood, unquestionably, should not under any circumstance be struck out or redacted! This will catch you in the heart, like it should. The poem concludes:

I flip through the pages of

my book. Reading Darwish at Qalandia

is a provocation.

I confront the bare Iron grids,

they are bone waiting for skin,

the toothed bars not wide enough

to squeeze a single orange in.

(21)

To even read poetry, here the poetry of Darwish, in such a context is a provocation. Like the final lines of ‘Love Poem to consciousness’ it is impossible to not confront:

I know this now, my being contracts and expands

with the land, boundless.

I know this, too: If ancestral homeland

gets me killed someday,

I’ll die like our trees, standing up.

(100)

Faced with confrontations of the most unjust and horrific death, of horrors seemingly unimaginable, as well as the knowledge of so much love and beauty in our hearts, I suppose some people also feel poetry is somehow a trivial response, somehow just a frivolity in the real fight against oppression or the deep appreciation of nature, life, humanity. This, Sara M Saleh’s The Flirtation of Girls reminds us, is simply not the case. Her poetry is about our very humanity, all of our humanity, it is life affirming, a powerful part of remembrance, for grief, and therefore love, and a powerful way for us all to imagine the world we need to exist into being. It is utterly crucial. I cannot recommend this book highly enough, it is stunningly brilliant. Saleh is a truly incredible poet and this is an astonishing debut that everyone should read.

Citation

Said, Edward W. The question of Palestine. Vintage, 1992.

KATIE HANSORD is a writer and researcher living in Naarm. Her PhD was completed at Deakin University. Her research interests include gender, poetry, feminism, disability justice, decolonisation and anti-imperialism.

August 14, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Dirt Poor Islanders

Dirt Poor Islanders

by Winnie Dunn

Hachette

ISBN 978-0733649264

Reviewed by ISABEL HOWARD

Intercultural struggle is the main question at hand in Winnie Dunn’s Dirt Poor Islanders: how do you define yourself between two different cultures that shape every aspect of your life? Dunn’s novel is written from the perspective of Meadow, a young, mixed-race Tongan and white girl growing up in Mt Druitt in the Western suburbs of Sydney and traces her gradual assertion of who she is as she becomes a young woman. With a liberal peppering of millennial Australian and Tongan cultural references it explores themes of girl and motherhood, sexuality and poverty. But at its crux, it provides an internal viewpoint for readers to witness Meadow’s evolution from rejection of herself and all things Tongan, to understanding where she belongs between two cultures and racial identities, and within the complex map of her family.

Built around Meadow’s gradual growth and self-acceptance, the novel adopts the arc of a bildungsroman, and is split into four sections: Soil, Bark, Salt and Blood. At the start of each section, we’re greeted by a written retelling of a traditional Tongan story, such as the story of Va’epopua at the start of Soil:

The lagoon stretched further and so too did the demi-god. From coral to seaweed to salt to wave – it became clearer to him that everything emerged in pairs. Somehow, he knew that he could not be made of woman alone. So, when the demi-god’s calves became as wide as stumps, he questioned his grounded mother yet again. ‘I am made from what?’

Slowly planting taro with her stiff knuckles and gnashing inside her cheeks, Va’epopua whispered, ‘Different.’(4)

Each of these retellings foreshadows its respective section, like the parallel in this excerpt between Meadow’s mixed racial identity and Va’epopua’s son’s parentage. By using and repeating particular Tongan phrases and motifs in these retellings, Dunn alludes to a long-lived oral history and a set of values that differ from dominant Western ideas held in Australia, and she weaves connections to these retellings throughout the story as important symbols of Tongan identity, such as childbirth, soil, and Tongan foods. In fact, the whole novel is a collection of experiences laden with meanings and lessons that help Meadow make sense of her identity, emulating the nature of oral storytelling as a means of transmitting history and values.

At first, I felt that this structure meant that the story lacked a momentum I’ve come to expect from Australian fiction, in that it was missing a central conflict or mystery to drive the plot. However, as Matthew Salesses’s explains in Craft in the real world, “causation in which the protagonist’s desires move the action forward” (27) has been dictated by dominant Western ideologies of literature as the hallmark of effective fiction, leading us to undervalue traditions that have priorities other than a story’s start or end (98). Thinking about this made me realise that it was my expectation that was lacking: Dunn’s work doesn’t offer a denouement of practical solutions to Meadow’s problems because it rejects this Western storytelling vehicle in favour of a form that resembles cyclical storytelling. It emphasises understanding and interconnectedness and, basing my knowledge in Dunn’s retellings, it engages with the essence of Tongan storytelling traditions. It’s an innovative choice, and its delicate execution marks Dunn as both an original and skilled writer in the Australian landscape.

Beyond structure, Dunn centres Tongan-Australian experiences through just about every aspect of the novel. She provides nuanced representations of Tongan-Australian people, spaces, language and kinship, suffused with so much detail and feeling that her lived experience shines through, as seen in careful details like these:

My grandmother stepped out, dressed in an entirely new outfit – a shimmery puletaha with gold embroidery. Holey ta’ovala around her waist. Ta’ovala was funny like that; the poorer it looked, the richer it was, because it meant the garment had been passed down for generations. (206)

But Dunn resists one-sided glorification to represent the complexity of Tongan-Australian culture in full. She underscores the strong bonds between Tongan people and their “togetherness,” (40) but doesn’t shy away from how those bonds can become problematic, such as how Meadow’s family expects her aunt to sacrifice her intimate relationship with a woman for the sake of their traditions (163). As a woman personally living these experiences, in a country where Tongan people are plagued by negative stereotypes, I’m certain that this is a challenging step for Dunn. But by taking it with care, she’s created an earnest picture of what it means to be Tongan in Australia: the beauty and the ‘dirt’.

By being selective and sparing in how she explains Tongan culture and language, Dunn is unapologetic about prioritising a Tongan-Australian audience and making them the cultural insiders of Dirt Poor Islanders. For those who aren’t cultural insiders, this could make the novel an occasionally alienating experience – some might even argue that the lack of explanations, or the lack of provision for cultural outsiders, prevents them from identifying with Meadow and takes them out of the flow of the story. However, Dunn has made her choice clear, and I would argue that, in a publishing industry where this is the very first novel written for a Tongan-Australian audience, it adds significant value for cultural insiders that would be diminished by catering to the white gaze. Rudine Sims Bishop explained that seeing ourselves represented is a powerful and validating experience, and it’s just as important to be exposed to the experiences of others – a statement I take to mean as that, for some readers, being made to feel like an outsider by Dunn’s work is a good thing.

As someone who isn’t Tongan nor speaks Tongan, I did occasionally get thrown by Dunn’s frequent Tongan references. Upon reflection, though, I realised that this kind of partial understanding is also a common mixed race, or ‘third culture kid’, experience that I can identify with: growing up surrounded with a mix of cultures and languages, I was often in situations where I didn’t understand the words or references around me. It’s a common, isolating experience that Dunn teaches and encourages readers to empathise with by presenting it through Meadow, who partially understands everything herself.

In a similar vein, Dunn explores racial identity for mixed race and Tongan people in Australia with sensitive accuracy. Racism is the very first thing we see Meadow experience: her white neighbour yells racist abuse at Meadow’s Tongan grandmother, causing Meadow to decide to never work with her on a ngatu again (10) and sparking her association of being Tongan with dirt and muck (112). Further on, there are frequent references to Meadow or others wanting to be pālangi (50), and accusations that Meadow is not Tongan enough: ‘Me and Nettie steered clear of proper Islander girls when we met them at Sunday school in the halls of Tokaikolo. Those mohe ‘ulis demanded we spoke Tongan too, and when we failed, they mocked us. Together, Tongans were always trying to prove how real or fake each of us were. Nettie and me, we were plastic.’ (89)

With passages like this, Dunn draws attention to the ways in which we racialize people based on their cultural or linguistic knowledge and language. She shows how external messages can influence one’s racial identity and foster internalised racism, in that Meadow initially hates being Tongan, but also defines herself ‘as half and never enough, hafekasi’ (271). But to rebut the often harmful assumption that these feelings might be intrinsic or inevitable, Dunn presents us with Meadow’s rage at the injustice of racist stereotypes during class (141) and, eventually, her realisation that she can define herself differently: ‘No one could live as half of themselves. To live, I needed to embrace Brown, pālangi, noble, peasant, Tonga, Australia – Islander.’ (275)

Dunn actively rejects the ways in which Tongan and mixed-race people are stereotyped and made to feel less than their counterparts in Australia, and it’s this aspect of her writing that I’m most grateful for. Many of Meadow’s experiences and feelings are reflected in my own life as a mixed-race Filipino-Australian woman, and it’s refreshing to not just see those experiences on the page, but to see how Dunn presents them as steps in a journey of understanding oneself.

There’s plenty more to examine in Dirt Poor Islanders, such as sexuality, motherhood, and family violence. But in the interest of writing about what I know and what I believe to be the heart of Dunn’s novel, I’ve focused on her exploration of race and culture. Despite the differences between being Tongan and Filipino, reading Dunn’s work felt like slipping on a well-worn t-shirt in how empathetically she writes growing up not-quite-white in Australia. It’s a generous, powerful debut novel, narrated with a vulnerable voice, and much like Meadow’s many mother figures, it challenges its readers while fostering love and understanding.

Citations

Salesses, Matthew. Craft in the real world. Catapult, 2021.

Bishop, Rudine Sims. “Windows and Mirrors: Children’s Books and Parallel Cultures.” 14th Annual Reading Conference 1990, California State University, 5 March 1990, pp. 3-12, files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED337744.pdf#page=11.

ISABEL HOWARD(she/her) is a Filipino-Australian writer based in Lutruwita / Tasmania. Her creative work has appeared in kindling & sage, and she is currently in her Honours year studying creative writing at the University of Tasmania.

August 14, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Kairos

Kairos

by Jenny Erpenbeck

translated by Michael Hofmann

ISBN 9781783786121

Granta

Reviewed by GAN AINM

It’s hard to avoid the idea of allegory when approaching Jenny Erpenbeck’s International Booker Prize-winner, Kairos. Right from the cover, we are told by Neel Mukherjee that ‘Erpenbeck has written an allegory for her nation, a country that has ceased to exist— East Germany’. The Booker Prize’s own website asks us to consider the merits of reading Kairos allegorically, and most reviews will come down on one side or the other regarding the device’s efficacy.

The story of Hans and Katharina, two East German citizens in the latter years of the state, begins at a moment of, seemingly, good fortune; a chance meeting on a bus in which passions are ignited and an affair ensues. The novel itself, however, begins long after this, when Katharina hears of Hans’ death and begins to sift through boxes of letters, diaries, notes and other refuse of their relationship. Hans is a former Hitler Youth, current writer, and married with a child. Katharina, far younger, was a member of the Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation, a socialist youth group collective designed to uphold the values of East Germany. Hans wields a patriarchal authority over Katharina, as well as, via his several affairs, his wife and child. He is well-travelled and learned, and his experience of life before (and beyond) the wall lends him an autocratic propensity that he wields culturally, familially, and sexually. There is, then, from this initial kairos, or ‘critical moment’, of their meeting, a disparity between the two lovers, one reflective of those between East Germany and its citizens. The GDR was the socialist-controlled portion of Germany following the end of WWII. To maintain order and prevent dissent, the government placed restrictions on the freedoms and movements of its citizens to travel to the capitalist West Germany over the Berlin Wall. By the late 80s, when the pair meet, they are living in a failing state, where the tensions spawned by government overreach would soon cause its complete (and in the case of the Wall, literal) collapse.

The novel makes this allegory clear through its explicit positioning of the personal and political:

Up and down. End of season sales, says her cousin. Bargain basement prices. Words Katharina needs to learn. She tries to remember what she was taught in civics about the difference between use value and exchange value. // And not once does the phone ring. // Is Hans sleeping with his wife on their vacation? Up and down, up and down, until everything that’s for sale is practically given away.

(p. 77)

Step by step, Katharina measures herself against her state, which has been generous to her and now counts on her to be generous in return. // Did he give himself up to her, or she to him? Or, if love is serious, are they indistinguishable?

(p. 86, 98)

The same can be said of the novel’s conspicuous allusions to walls:

Before they head out again, Katharina sees a photo of Hans on the desk. Can I have that? she asks, and Hans asks back: As a wall to contain imagination? (p. 30)

The immediacy with which these comparisons and references are made (being set up and paid off within a few pages if not the same paragraph) can sometimes work against the novel and reveal the limitations of a simple A = B, B = A comparison. However, I mention the debate around the novel’s allegorical reading up front in order to posit that Kairos is in fact far more interesting than the elevator pitch version of its premise; it is evident that the majority of Erpenbeck’s actual compositional choices point towards something at once broader and deeper.

Tension and unease is baked into Erpenbeck’s writing. The lack of clear subjects and verbs throughout the novel’s persistent use of sentence fragments leaves the reader dependent on their surrounding context, perhaps reflecting not just the young Katharina’s dependence on Hans, but the dependence of both upon the state. The use of run-on sentences speaks to a similar kind of reliance, this time the need for those in power to connect dots, draw conclusions, stoke suspicions; their frenzied amalgamation and need to reach and infiltrate everything is a kind of paranoia based in the fear of the agency of others, and the possibility for freedoms to undermine the (im)balance of power. Control is the shared element of these two seemingly incongruous techniques, and it is a control wielded by Hans as well as (and because of) the GDR.

Having lived through its creation, Hans sees the socialist utopia (and, because he is the one betraying his wife, the affair) as generative. It is not a preconditioned, or in any way stable, S/state, but a system which requires maintenance, regulation, continual reassertion and the quelling of potential threats to its stability. Such betrayals take the form of infidelities (against him) which engender ever greater controls that limit the freedom of dissidents. What Katharina’s affair-within-an-affair seems to represent for Hans, then, is the fear of her freedom, of her agency in moving beyond imposed bounds and barriers, and a choice in where her loyalty, her love, her body, can lie. As with all betrayals by combatants, there are punishments, and in her reaction to these, we again see the infusion of the personal and political, with Katharina initially reluctant to cross the Berlin Wall to the (comparatively) free and capitalist West. These sharp psychological observations shine through, and indeed create a powerful parallel between the troubled lovers and the collapse of East Germany, and yet Erpenbeck pushes her writing further.

There is a conspicuous and purposeful lack of speech marks throughout the dialogue, and even occasions when dialogue is not laid out traditionally:

Well, says Hans, I can’t swim. Why’s that? The water was too cold for me. Katharina shakes her head, disbelievingly. Really? she asks. And he replies: No, not really.

(p. 57)

This technique may again point towards the idea of control and the compelled language of totalitarian states; arranging the dialogue as we would a traditional paragraph seems to take away the agency of what is being said. However, it may also represent a kind of finality, or perhaps inevitability, and this may be the book’s most devastating decision.

If speech here is not granted a special, interventionist category, via speech marks, then these are not assertions being injected into the world, but solidified, spatio-temporally fixed elements of the world. They are past, no different in kind from the scenery or sensorial recollections of a now-defunct nation, recalled in imperfect fragments by the frame narrative. This device, where we find an older Katharina reflecting back with a general lack of the dependent fragments, furthers this conclusiveness with a perspective of birds-eye omniscience:

It feels good to be walking beside him, she thinks. // It feels good to be walking beside her, he thinks.

(p. 19)

He thinks, as long as she wants us, it won’t be wrong. // She thinks, if he leaves everything to me, then he’ll see what love means. // He thinks, she won’t understand what she’s agreed to until much later. // And she, he’s putting himself in my hands. // All these things are thought on this evening, and all together they make up a many-faceted truth.

(p. 27)

This all-knowing perspective, like the other devices here, speaks towards a certitude, to what is doomed to happen within an imbalanced relationship from the instant of their meeting; that critical moment contains within it a ‘good fortune [which] implied always [a] misfortune that was not just equal and opposite, but in its potential for harm, perhaps even much greater’, where ‘anything seems possible, anything good, everything bad’ (p. 91, 117).

To speak briefly of Michael Hofmann’s English translation of these techniques and themes, the aforementioned devices are all preserved effectively and reverentially. Other moments, however small, seem to take more liberties; it’s difficult to see, for example, how the line “that strange word ‘believe’, with ‘lie’ in it, is still going through her head when he has pulled down the straps of her dress” could maintain its specific wordplay (and implication) in the original German (p. 46). While this might seem pedantic, I mention it only for those with the capacity to read this text in its original language.

Erpenbeck’s book is crushingly absolute. It is tinged not just with the finality with which a memory is remembered, or a fragment recollected, but the finality that reveals the inevitable, and within the inevitable lies the inherent. Power imbalances do not become manipulative and abusive, but are abusive, always and already; they require a monopoly on agency, increasing coercions and restrictions on freedom lest the authority be challenged, or abandoned.

Everything in Kairos seems to speak towards this certitude, but it is hard to see the novel as defeatist. If the book does indeed function as an allegory, then it is, like all allegories, a warning, and an act of defiance. A warning cannot be for ‘a state that has ceased to exist’. It can only be for a potential, a future, dare we say a present, one in which there opens up the chance to heed the warning; to do, to act, to be, better.

GAN AINM is a writer born, raised and living in Lutruwita/Tasmania, currently undertaking a PhD at the University of Tasmania, and whose fiction and non-fiction has appeared in Island Magazine, and received second place in the University of Essex Wild Writing Prize.

July 29, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Lindsay Tuggle is the author of The Afterlives of Specimens (2017), which was glowingly reviewed as a cover feature in The New York Review of Books, American Literature (Duke UP) and American Literary History (Oxford UP). Her debut poetry collection, Calenture (2018), was one of The Australian’s Books of the Year, shortlisted for the Association for the Study of Australian Literature’s Mary Gilmore Award and Australian Poetry’s Anne Elder Award. Her work has been supported by numerous international grants, including the prestigious Kluge Fellowship at the Library of Congress, and a Travelling Fellowship from the Australian Academy of the Humanities. In 2023, Lindsay was a Writer-in-Residence at Château d’Orquevaux in France and Bundanon Trust in the Shoalhaven of Australia.

Lindsay Tuggle is the author of The Afterlives of Specimens (2017), which was glowingly reviewed as a cover feature in The New York Review of Books, American Literature (Duke UP) and American Literary History (Oxford UP). Her debut poetry collection, Calenture (2018), was one of The Australian’s Books of the Year, shortlisted for the Association for the Study of Australian Literature’s Mary Gilmore Award and Australian Poetry’s Anne Elder Award. Her work has been supported by numerous international grants, including the prestigious Kluge Fellowship at the Library of Congress, and a Travelling Fellowship from the Australian Academy of the Humanities. In 2023, Lindsay was a Writer-in-Residence at Château d’Orquevaux in France and Bundanon Trust in the Shoalhaven of Australia.

Read more at http://www.lindsaytuggle.com

The Arsonists’ Hymnal

Our story starts in the field

and ends in the bath

or vice versa.

I can no longer remember when things came full circle,

when our endings and beginnings began

to eat their own tales.

In the middle, there is fire.

Summer was not yet the vast,

burning thing it has become.

Arson is a form of prophecy.

Flames have tongues, and so do we—

whether we use them or not.

The fires were warning us,

all this time.

No one believes a prophet,

until it’s too late.

That night, we lay on the grass,

watching for heat lightening.

We cannot sleep without seeing

that jagged rupture in the sky,

a tangle of stars and satellites

discernible only by blinking proximity.

After the lightening

our adolescent

poison quickens, then recedes.

After, we sleep.

But not tonight.

Tonight, we speak again in our mother tongue,

a dual fluency we alone share.

At first, we don’t hear the shift.

Slippage is like that, both sudden and gradual.

They forced it from us long ago

or so it seemed.

We remember the doctors’ creeping hands

encircling our throats,

probing the wet insides of our mouths.

A needle. A parade of arms.

Slowly, we learned to speak

the Queen’s tongue.

We forgot to remember

the poem unfurling

in the air between my sister and I,

the slow dance of our exhalations.

Then,

at thirteen,

a murmuration escaped.

Our bodies begin

to stretch and swell.

Our marrow aches.

We are always hungry.

Games over who can eat more, or less,

then dance til exhaustion.

Our limbs crave sleep,

but are too long for our narrow beds.

So we lay in the field,

waiting for the heat to break into light.

We didn’t set the fire.

Not with our hands.

We dreamed of burning for so long,

at last the lightening answered our call.

We lay still as the grass flumed ever closer,

let the dying embers kiss our skin.

In our secret tongue, we agreed

to remain, unmoving,

to let the ending write itself.

Did we wake in the bath

or the grave?

I can no longer recall

which of us resides underground.

Oracles and fire-eaters share fatal tendencies.

It is a dangerous business, prophecy.

Paralysis is innate, in the face of extinction.

Fawn response on a global scale.

When ashes fall from your mouth,

remember, you asked for this.

Swallow hard, sister.

One last time.

July 16, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Martyr!

Martyr!

by Kaveh Akbar

Pan Macmillan

ISBN: 9781035026074

Reviewed by JAMES GOBBEY

If the mortal sin of the suicide is greed, to hoard stillness and calm for yourself while dispersing your riotous internal pain among those that survive you, then the mortal sin of the martyr must be pride, the vanity, the hubris to believe not only that your death could mean more than your living, but that your death could mean more than death itself—which, because it is inevitable, means nothing.

(250)

Dying is individual, but death punctures the social, diffusing its impacts among those that remain. Martyr! then asks: is there meaning to be found in death? What lives on with the people that remain? What makes a martyr?

Kaveh Akbar’s debut novel, Martyr!, sees the established Iranian-American poet turn his attention to a new form. His novel asks uncomfortable questions in the name of identity and grief, culminating in a work that attests to the singular devastations that make up collective loss. And yet, despite a fascination with the lingering potential of death, Akbar achieves a lightness that lifts his novel beyond simple pessimism.

Martyr!’s focal character, Cyrus Shams, is surrounded by death. It permeates his life: he works at a hospital, playing sick for medical students to practice counselling the terminal; he is a recovering addict, sure that every day of sobriety is a day of life he should never have seen; he is haunted by the memory of his mother’s murder in the downing of a commercial flight by a US navy cruiser. All of this death culminates in Cyrus’s fixation with, and desire to begin writing on, martyrdom.

The above extract, ruminating on the sins of suicide and the martyr, forms part of Cyrus’s work-in-progress: “BOOKOFMARTYRS.” This book helps structure Akbar’s novel, seeing the inclusion of poetry dedicated to famous martyrs, as well as passages of essayistic prose. These textual interludes feature at the turn of each chapter, alternating to also include transcripts, emails, and further details surrounding the flight on which Roya Shams lost her life. Because, ultimately, it is the ongoing impacts of Roya’s death that drive much of this novel.

Roya’s death is folded into the missile attack of Iran Air flight 655 by the USS Vincennes in 1988, which resulted in the murder of 290 civilians. The public memory of this attack is a site of contestation between Iran and the United States. In an interview with Nylon, Akbar explains, “When you say the Vincennes incident, people of a certain age will furrow their brows. It’ll sound vaguely familiar, but they won’t remember 290 innocent lives shot out of the sky. I’m fascinated by that. In Iran, they put it on postage stamps. They propagandize it. I’m fascinated by that, too.” The propagandization of flight 655 serves to make the civilians killed into martyrs. Their deaths assert the indiscriminate nature of the United States war machine, particularly when held against the failing memory of the United States public. In the aftermath of the downing of Iran Air flight 655, these deaths are given an ulterior meaning.

For Cyrus, this moment of tragedy is a starting point. When asked about the kind of book he conceives of “BOOKOFMARTYRS” being, Cyrus explains:

My whole life I’ve thought about my mom on that flight, how meaningless her death was … The difference between 290 dead and 289. It’s actuarial. Not even tragic, you know? So was she a martyr? There has to be a definition of the word that can accommodate her. That’s what I’m after. (75).

Cyrus initially determines his mother’s death to be without meaning—simply a number among many. And although we must reconcile that Roya’s death is “not legible to empire” (75), this novel expounds a more expansive view of the potential meanings that death can carry.

Foremost, Martyr! is a novel that takes the individual loss present in mass death and inspects it. Because, on some level, Cyrus is right. How do we feel the difference between 289 and 290 deaths? Rather than succumbing to the generalised negativity of significant loss, this novel takes a step forward to invigorate the connectivity of a single life—one marred by tragedy on a mass scale.

I purposefully call Cyrus the focal character of this novel. It is a simplification to call him the protagonist—or even the main character. Martyr! uses Cyrus as a centre from which to work outwards, extending from him to offer life and voice to surrounding people and characters. Primarily, these voices belong to family and friends, but genuine martyred lives are also evoked: namely those of Bobby Sands, Bhagat Singh, Hypatia of Alexandria, and Qu Yuan. These martyrs each feature as poetic subjects of “BOOKOFMARTYRS,” their historic deaths speaking to Cyrus’s negotiations with his own time and identity. Bobby Sands, for instance, has a poem written to him that begins:

there’s a Bobby Sands Street in Tehran

one block over from Ferdowsi Avenue,

that’s true, Ireland, Iran, interchangeable mythos

(97)

This poem binds Ireland and Iran, recognising their shared suffering at the hands of colonial powers; it draws together Sands and Ferdowsi—a Persian poet whose story is later retold in Martyr!—creating a textual crossroads at which the two meet. Through Cyrus, through his human ties and writing on martyrdom, a world of active social ties is revealed.

The connectivity of Martyr! rejects the individualism that separates us from others, perpetuating apathy. In Akbar’s novel, the relationships that spring from Cyrus allow us to feel more. Throughout the novel we touch on the real lives of martyrs, but we also encounter Cyrus’s family and friends. We meet Ali, Cyrus’s father, who made ends meet throughout Cyrus’s childhood by working on a chicken farm; Arash, Cyrus’s uncle, whose time in the Iranian army was spent riding through fields of the dying dressed as an angel of death; and it is through chapters and passages such as these that we meet a clearer version of Roya, unaltered by the filter of Cyrus’s faded childhood memories—a woman who reveals, “I never really loved being alive” (145). These affecting connections extend to include others important to Cyrus: his best friend Zee, and the Iranian artist, Orkideh, whose imminent death becomes an art installation. By allowing the presence of this whole network of characters, we become more able to comprehend the dispersal of feeling that takes place when loss occurs.

Akbar does something vital in his depictions of social connectivity. He allows these characters the use of their own voices, rather than limiting them to the details known by Cyrus. Formally, as the novel shifts between characters, the point-of-view changes from its standard third-person to a more transparent first-person. While Cyrus is the centre through which we come to each of these characters, access to their experiences—their emotions—occurs through their own words. From this use of voice, these characters each come to exist as the centre of their own worlds, not exclusively the periphery of Cyrus’s, establishing the reality of their own personal connections, and a network that expands on and on.

This connectivity, this network of people who know and feel for each other to varying degrees, is how we come to parse through the distinct losses that make up mass grief. Martyr! does not deal with the problem of mass death—with the difference between 289 and 290—but it does create the space for us to feel the expansiveness of a single death, and from there we can begin to imagine the social impact of death on a large scale.

The expansive network depicted in Akbar’s debut novel alters how we come to understand the martyr, though perhaps creating more questions than answers. Finishing Martyr! I wonder if connection, if closeness, is one of the ways in which martyrs create meaning in death? Martyrdom does not exist in isolation: it holds meaning because of the life lost, and, crucially, the lives impacted. Cyrus Shams asserts that death, “because it is inevitable, means nothing.” But, death carries weight for those that remain. Grief is a testament to the life that did exist. Death’s inevitability does not necessitate the loss of meaning, rather meaning lives on with those that remain.

There is also something else buried in claims that death means nothing. Consider the civilian deaths of Iran Air flight 655: the grief felt for the victims; the meaning attributed to their lives; the violence of the US—none of this should be lessened by death’s inevitability. As state sanctioned mass murder continues in Gaza, we cannot say that death means nothing. To disregard the significance of death is to render oppressive systems acceptable, and, ultimately, this undermines the social world that connects us.

Works Cited:

Akbar, Kaveh. Martyr!. Picador, 2024.

Akbar, Kaveh. “In Martyr! Kaveh Akbar Is Thinking About Eternity.” Interview by Sophia June, Nylon, 2 Feb. 2024, https://www.nylon.com/life/kaveh-akbar-martyr-interview.

JAMES GOBBEY (he/him) is a writer and bookseller from lutruwita/Tasmania. His work has previously been published by Aniko Press and Togatus Magazine.

July 12, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

Moon Wrasse

Moon Wrasse

by Willo Drummond

Puncher and Wattmann

ISBN 1922571679

Review by MISBAH WOLF

When I first picked up Willo Drummond’s debut poetry collection, Moon Wrasse, I was torn between a deep panic of knowing I wanted to become mixed up in the muck, blood, and bloom of the work and wanting to also turn away from the words. Words are spells. Words are little invisible ties between what is captured and what is lost, and somehow, as if by magick, portals are opened for us to walk through. In a true sense, this is an offering from Drummond of a portal of initiation—you choose which kind—one you’ve already been in parallel with, one you have no memory of, or one you care enough to walk along with to experience and become more completely human.

I opened the book to the poem ‘Seed’ which, in a sense, introduces what I see as a quartet of work. I read;

At this season’s out-swelling

after the mangrove moon

she sets her grief in a small seed pod.

(7)

I, myself, had been dealing with ‘unexplained infertility of ten years, and I wasn’t ready to read it, but the book called out for a conversation with me. I recognized it within my own immediate framework as a book of invisible connective tissue, a witch’s book of shadows, both literary and psychic, between the dead, the dreaming, grief, the acute attention to the breath of things and the indexing of transformations. This is a book where surfaces appear deeper once immersed, where continual intertextuality adds further dimensions, and no energy is ever lost since all is transmuted. A pause must be taken, and a return, like a Joseph Campbell Hero/Heroine, is undertaken;

She’s looking for

a future to enframe the past

as it exceeds

it. Flickering familiar

like the pulse

of being needed.

(7)

Reading this work, I was able to chart a ship in the shadows of Drummond’s glorious book—through my own grief over childlessness, my estrangement from others/lovers, my deep love for ecology, for the mud and muck of various things I have lost, found, and re-imagined. These things grow in Drummond’s poetry through mud and shadow like mother mangroves, endangered blooms, and conversations with visceral transformations under ‘dappled light’. (60) Such love is to be invoked in the poem “Moon Wrasse” where the narrative etches through the shifting cycling as a lover/other/self that is;

here, moving in

our translucent

cocoon

‘self-made’ and safe

as houses— (60)

It is an homage to great love transforming and witnessing the beloved’s

new lucency—

clear as the blue

of your new man suit

sweet as the day

true as the day (60)

This enamoured lover/narrator bears witness/encourages and celebrates this alchemical corporeality with tender reassurance in this delicate liminal space,

holding hands

like younger lovers

in a film

in a dream.” (60)

The shape of the month as I read this work was also colored by other books at the same time. Fitting for such a book that plays, converses, and returns to dialogue entries, quotes, and habits of other poets and writers. Rest assured, Drummond includes notes about particular moments, words or passages from other writers in this book to show how interwoven and entangled this book is with others’ work. In The Childless Witch, Camelia Elias says: ‘The age we live in is, indeed, no longer an age of lamentation. We lost that art long ago’ (Elias, 2020). The reason I’m including this quote from Elias is that Moon Wrasse has developed a very delicate language of lamentation, with images of ‘striking,’ ‘scraping,’ and ‘digging,’ further propelled after Louise Glück—as in Drummond’s ‘The Act of Making,’ (11) using techniques of alliteration, words beating against each other, switching to words that require the tongue to be pushed gently through lips—there is a feeling when reading this poem and many like this, of incanting. In ‘The Act of Making,’ Willo Drummond employs a rich array of poetic techniques that enhance its incantatory quality. Vivid imagery and sensory language, such as ‘gardens fecund with memory'(11) and ‘imagined blooms heavy with the scent of hope,'(11) create an immersive experience, while enjambment ensures a seamless flow between lines, propelling the reader forward, as in

.How can you bear

so many imagined blooms heavy with the scent of hope

let go? (11)

The use of repetition and parallelism, like ‘day after day,’ adds musicality, and the alliteration and assonance in phrases such as ‘fluffed intentions’ and ‘solitary bees’ create pleasing sound patterns that my mouth wants to vocalise. Caesura introduces rhythmic breaks for emphasis/division/rupture of grief;

Unwomanly. Bent queen

brimful of love shame with nowhere to dig

in (11)

Also, the sharp juxtaposition of contrasting ideas, such as ‘love/shame’ and ‘hope/let go,’ deepens the poem’s emotional impact. Symbolism, unconventional syntax, and strategic line breaks contribute to the poem’s unique rhythm and pace, while personification and metaphor, like ‘remembrance scratches your knuckles’ and ‘bees hover, uncertain,’ imbue the poem with lyrical depth. These elements combine to make Drummond’s poem feel rhythmical and lyrical, making me want to read it out loud. And I do speak them and it is a pleasure to let the words slip and pause between my teeth and tongue.

We can look further into such poems as ‘Note to Self (in Novel Times)’ that inscribes like graffiti on an ancient/new wall to a future/past/now self, on a fridge pinned up by magnets to;

Remember to love

the world. Love

the wailing, rolling world;

the air; the wildness

of wind lifting a million kites

of change (72)

Such a poem circles back through voice, through lamenting, through oracle (as Earth) as change always present to call one back home. In The Childless Witch, Elias also reframes such a being as ‘able to cast a powerful spell of movement, a movement that goes from trembling, to dance, to the use of voice, the oracle and a state of grace’ (Elias, 2020). Looking through Drummond’s book, these states of ecstatic magic—shadowy and bright—are evident in the language and invocations that run rife throughout this collection. There is a language of lamentation here, as previously suggested—of that which will not grow among the commonly seen, and offers instead the witch’s second sight such as in the poem ‘Ways of Seeing.’ This narrator is pensive with ‘portents’- where moon cycles are traced and named;

While others turn with such precision,

radiant orbs—content

filled—I dream of conjunctions

luminous alignments

stackings of hope (20)

This second sight seems always pensively aware of the delicate nature of life in ‘The Art of Making’ that we as readers intrude/bear witness/are gathered round to see ‘Somewhere, a ghost orchid blooms’ (12) This rare orchid/child/being blooms only once a year, pollinated by mimicking male sphinx moths deep in forests where it sucks the moisture from the air.

With this invitation from Elias—’trembling, dance, voice, oracle, and grace’ resound through Drummond’s work. There is even a further complexity established by which Drummond records in her notes at the back of Moon Wrasse that the line from the poem ‘Seed’,

where what cannot be

is (8)

gestures to Jennifer Moxley’s claim that ‘lyrical utterances record voices structurally barred from social and political power.’ (Drummond, 76). This first poem is set adrift from the four sections as a poem in motion, of coming up from elsewhere by will;

here in the lyric tense

she stills to witness

each furred pod/

gain its wild purpose—’ (7)

This feels like an invocation to voice, to the tiny seed to speak its will, to inscribe and to create. Again, a voice unheard/heard is set in motion in ‘Sail,’ where the other’s silent voice is;

voice, a gaping mouth, calls

from a crack in the world: desolate

wind, sweep my knowledge

into oblivion, drop me back

into the well. (21)

Read it aloud, read it softly and it could well be the words of shamed/guilty/lamenting Medea, such a misunderstood and maligned witch, also a favourite childless witch of discussion for Elias. (Elias, 85)

I have enjoyed framing Drummond’s work as part of a Quartet, a story perhaps like a cycle connected in four parts, likened to the four major phases of the moon—the new moon, the first quarter, the full moon, and the last quarter—because so much of the work makes invitations, invocations, and references to the moon. In Drummond’s section ‘The Art of Losing,‘ ‘Of Finding and Not Finding Levertov,’ ‘Forming and Transforming,’ and ‘Arriving,’ why not take this as a template, traversing phases of the moon? Considering that in my reading, I felt poetic tidal shifts under the witch’s tools of moonlight and water, whether inscribed as bodies, mangroves, fish in moonlight, or rare blooms sucking at the mist. I enjoy mysteries and puzzles and esoterica, so I have dug into this deep pleasure in making these connections through the language or merely literary pareidolia. But there are clues to make such connections, such as mention of the ‘spun to song of sun played at waning moon‘ (61) in ‘A Promontory/A Memory,’ and, of course, the poem ‘Moon Wrasse’—the fish that changes sex to mate and has a crescent moon on the caudal fin, the energy of such seems to suggest a letting go of what has been and finding hope in a ‘translucent cocoon'(21) moving towards the new moon. The new moon is, of course, the dark unseen moon. It is the place that calls for presence and to explore the unseen, and I pose that this is the beginning phase we enter from the start of the book, with poems that seem to scry into the unseen. Considering the first poem ‘Seed’ moves from the lines;

In waning luminescence

on the aqua-terrestrial shore

she trains her eye

to velvet vivipary

on very salty water

She’s looking for

a future

to enframe the past

as it exceeds it. (7)

It is the entrance towards the darkness of the new moon in the first quarter ‘The Art of Losing.’ In the new moon phase, there is no visible moon in the sky, and it is the time to explore the unseen, to call for presence, and to stretch the grief unfathomable into song and poetry.

The first poem of this quarter, “The Act of Making,” is indeed what Camelia Elias calls ‘the lost art of lamentation’(Elias, 15), again inscribing vividly with a question;

How can you bear

so many imagined blooms heavy with the scent of hope

let go?” (11)

Set behind this poem is hauntingly Glück’s ‘The Wild Iris’ (“Hear me out: that which you call death I remember”) like the wild Iris, reborn, returning from dissolution to ‘find a voice’—here Drummond masterfully extends the deep mystery of Glück’s poem of death and rebirth, and continues the esoterically charged moment to look for portents, to have knowledge of the rare ghost orchid ready to be born.

In this first quartet too, ‘Up to Our Knees in It’ explores the unseen mother mangrove beneath the surface, extending and connecting, living anywhere despite the ‘cinema seats and soft drink cans‘ (15) thrown into the waters.

Furthermore, Drummond’s poetry, particularly in the sequence ‘The Rilke Index’ and ‘Open Secret,’ showcases a profound engagement with the poetics of Rilke and Levertov. By using index items as titles and integrating verbatim citations, Drummond creates a rich intertextual dialogue. This approach pays homage to Levertov’s method of personal indexing and underscores Rilke’s enduring influence on Levertov’s work, which in turn feeds and nourishes Drummond’s. The titles and substantive material, marked by italics for Rilke and inverted commas for Levertov, reflect a meticulous synthesis of response, citation, and allusion (Drummond, 2021).

Central to Drummond’s poetry is the theme of attention and participation, echoing Rilke’s poetics. In ‘The Rilke Index,’ phrases such as ‘True singing/ is a whispering’ (35) and ‘It hums along the avenue of original grief polished as a stone’ which highlight the importance of quiet, attentive engagement with the world (Drummond, 2021). Similarly, ‘Open Secret’ uses the imagery of a Peltops singing her inwardness to suggest a deep, participatory observation of nature.

Drummond’s work exemplifies Rilke’s Ding or thing poetics through its focus on sensory, concrete experiences. The detailed imagery in ‘The Rilke Index’ and the tangible descriptions in ‘Open Secret’ underscore the importance of observing and interacting with the material world. This attention to the physicality of things aligns with Rilke’s belief that true insight comes from an intense, participatory observation of one’s surroundings.

Reflecting deeply on the nature of creation and the self, Drummond’s poems reveal a continuous journey of self-discovery. ‘The Rilke Index’ and ‘Open Secret’ meditate on the interconnectedness of self and creativity, suggesting a composite identity shaped by various influences. Drummond’s imagery, such as ‘the owl afloat, the white egret’ and ‘the blood, the plough, the furrows made,’ captures the essence of seeing with ‘second sight,’ a deeper, intuitive understanding of the world (Drummond, 2021). This second sight is the sight of the witch, the seer, the being that dares, even when nothing necessarily will come of it—to look and to record presence/absence. Not only is second sight present here, but also the Owl—the totem of Hecate—Queen of Witches, and the action of tilling the land with blood and earth, much like the ingredients for a spell.

Willo Drummond’s poetry collection extends the poetics of Rilke and Levertov, emphasizing immersive conversations with the world—the unravelling power of careful observation and recordings. This work also creates carefully layered, intertextual dialogues. These inscriptions highlight the profound connection between self/other, the environment/body, second sight/inscription—all of which is the (witch’s) work of invocation with moon, of birth, death, rebirth, of longing (and the language of lamenting), and a complete presence of ritual observation, a conversation with invisible/visible forces transmuting. This book is an homage to love and magick and finding ways to reinscribe very necessary and vital voices and existences that have slipped/been silenced/written over/unpublished/forgotten. But it is also more than an homage—it is script that spells out the nature of time, looks closely at the Fibonacci spiral of bodies in presence with each other, of lamentation and joy rupturing through—detailed and woven with the echoes of other writers and poets, insistently in deep relationship to ecology, to the unseen dance of interconnection, such as the spellcasting in ‘All of it’ as ‘an ecology of selves’ (67) which with tremulous blooms/hands/words/voices reimagined worlds, relationships and love.

References:

Drummond, W. (2021). The Rilke Index. TEXT Special Issue 64: Poetry Now, eds. Jessica L. Wilkinson, Cassandra Atherton & Sarah Holland-Batt.

Drummond, W. (2023). Moon Wrasse. Puncher & Wattmann.

Elias, C. (2020). The Childless Witch: Trembling, dance, voice, oracle, grace. EyeCorner Press. ISBN 978-87-92633-57-6.

June 26, 2024 / mascara / 0 Comments

The Djinn Hunters

The Djinn Hunters

By Nadia Niaz

Hunter Publishers

ISBN: 978-0-6453366-9-6

Reviewed by JAVARIA FAROOQUI

The Djinn Hunters is a literary fusion of colours, words, shapes, and heritage, which has been carefully crafted in very interesting and distinct poetic styles. Nadia Niaz plays with the strands of her memories of Lahore to build evocative narratives in the short space of her poems, which occasionally carry elements of horror and the uncanny. Each of her fifty-one poems in this collection exhibits a wide range of expression and literary finesse that provides a refreshing, consistently engaging reading experience.

The horror in The Djinn Hunters is not meant to surprise the readers into a terrifying shock, rather it aims to disturb the very core of everyday existence. The first poem, “A Map of Mothers,” is primarily about the transmission of traits from female ancestors and the genetic inheritance that spans generations. However, Niaz’s dexterous use of simple words infiltrates the generational story line, unsettling readers with the image of grandmother and great-grandmothers haunting the voice of the persona. Absence of punctuation not only scaffolds the sense of continuity but also a deep feeling of horror:

I carry my mother in my mouth

in teeth and warm

bladed tongue

one grandmother, long absent

haunts my speckled skin

the rhythm of my feet

the other finds herself

in the set of my chin

the stubborn song in my belly

(1)

The poem starts with the imagery of carrying the mother in one’s mouth and concludes with varied maternal legacies interweaving and moving towards a surreal and ambiguous sense of belonging. The absence of pauses around “home” emphasizes the continuous evolution of human inheritance and gestures towards the uncanny behind the word that mostly signals safety and surety. The way in which the poem moves forward accentuates the haunting presence of ancestors within an individual’s identity, reminding us of pasts that perpetually influence the present:

great-grandmothers twine

in my hair, lurk in my bones

score my palms with their directions

each one pulling a different way

each one pointing towards home

(1)

The collection boldly utilizes poetic forms that blend verse and prose in engaging ways. The experimentation with form sometimes includes lines of varying lengths or concrete shapes, or some visually absorbing style like the one used in “A Dream of Daadi’s Paan Daan.” The consumption of paan, a mouth refreshment made from betel leaf popular in South Asia, has strong associations of tradition and culture. The paan holder, or paan daan, has a significant material value because of its association with the elders in South Asian households, and as such it symbolizes a sense of cultural rootedness and refinement. Niaz enhances this cultural reference by incorporating a unique visual element in her poetry. She prints four words, “roll,” “chew,” “spit,” and “fold” in grey ink behind the main text in black, inviting readers to decipher the entire process of paan consumption that involves rolling and folding the leaf, chewing the leaf, and spitting out the excess red substance (3). This creative approach not only adds depth to the poem but also engages readers in an interactive exploration of cultural heritage.

The Djinn Hunters extends its thematic reach well beyond its primary focus on djinns and a distinct sense of horror, to present a rich tapestry of different subjects. As a native of Lahore, I found Niaz’s striking and picturesque descriptions of the city’s sights, sounds, and smells particularly resonant and evocative. She manages to capture the essence of Lahore with meticulously crafted sensory details that allow readers to become part of the vibrant atmosphere displayed on the page:

The corners of this city sag under stories of generations

more numerous than the grains of imported sand lining

its avenues poised to be mixed into concrete buildings

(“Fine Aggregate” 23)

Heritage, continuity, culture, and belonging are the themes that run throughout this collection and scaffold the stylistic experimentations. There are sub themes of romance, politics, and feminism that emerge from the crafted verses in the form of powerful statements and images. For example, in the poem quoted above, a simile of pomegranate is used for young women walking on the streets:

Young women wander under strict instructions to stay close

crowded as pomegranate seeds, skins leathered against leers while

their mothers pick stones from rice and dhal and swallow smoke

(23)