Elleke Boehmer was born in Durban and lives in Oxford. She is the author of five novels including Screens against the Sky (1990), Bloodlines (2000), Nile Baby (2008), and The Shouting in the Dark (2015). Screens against the Sky was short-listed for the David Higham Prize, and Bloodlines for the Sanlam Prize. The Shouting in the Dark was long-listed for the Sunday Times prize (South Africa). She is the author and editor of over fifteen other books, including Stories of Women (2005), Postcolonial Poetics (2018), and a widely translated biography of Nelson Mandela (2008). Indian Arrivals 1870-1915: Networks of British Empire (2015) was the winner of the biennial ESSE 2015-16 Prize. South, North is her second collection of short stories, following Sharmilla, and other Portraits (2010). The Australian edition of The Shouting in the Dark, together with other writing about the global south, is coming out from UWAP in early 2019.

Elleke Boehmer was born in Durban and lives in Oxford. She is the author of five novels including Screens against the Sky (1990), Bloodlines (2000), Nile Baby (2008), and The Shouting in the Dark (2015). Screens against the Sky was short-listed for the David Higham Prize, and Bloodlines for the Sanlam Prize. The Shouting in the Dark was long-listed for the Sunday Times prize (South Africa). She is the author and editor of over fifteen other books, including Stories of Women (2005), Postcolonial Poetics (2018), and a widely translated biography of Nelson Mandela (2008). Indian Arrivals 1870-1915: Networks of British Empire (2015) was the winner of the biennial ESSE 2015-16 Prize. South, North is her second collection of short stories, following Sharmilla, and other Portraits (2010). The Australian edition of The Shouting in the Dark, together with other writing about the global south, is coming out from UWAP in early 2019.

Evelina

17:30

Evelina liked to hang around airports though, till today, she had never yet left an airport on an aeroplane. She liked to sit in the arrivals halls, in the coffee place close to the exit where families waited with balloons and smiles. She liked to absorb the ambiente, she preferred the Spanish word. She was absorbing it now, though in departures not arrivals, the café alongside the security gates, drinking her coffee and smiling as she watched the families smiling. It made her happy, that she could be included in their ambiente though she wasn’t required to say a word.

Her airport hobby had started a few years ago, three or four, she couldn’t remember exactly, back in the old century, the day she said goodbye to her best friend Marta. After her marriage went bad Marta had decided to make a clean break. Evelina and Marta had sat here in the same café, Marta retouching her lipstick, peering with narrowed eyes into the clip-open lipstick case she always kept in her bag.

Evelina had watched Marta walk that day through the departure gates sobbing into a tissue but with a kind of skip of her left heel, a definite spring in her step. Watching Marta’s departing back Evelina couldn’t help noticing the spring.

These days Marta was teaching languages in Spain, near Toledo. She was earning good money and seeing someone, she wrote, a nice teacher at the secondary school. Although she worried sometimes that he was so much shorter than herself. What their future children might think.

Their other friend, Teresa, mouthy Teresa, took the same exit route a year or so later. Again Evelina came to say goodbye. Again she bought a round of hot chocolate here in the café, and again stood with her face pressed to the security glass, watching Teresa sink down the long escalator to the departure gates, Teresa waving and smiling and then as she stepped off the escalator quite briskly tucking her tissues away in the side pouch of her bag.

Teresa had aimed to join Marta in the language school in Spain but then she had got talking to people, and people had talked nicely about her, so now she was working on cruise ships in the Caribbean. Everything had changed for her and was raised up to a new level, and now, Teresa wrote in her last birthday card, it should be Evelina’s turn. Now Evelina had her chance to go away like the others. She should grab the opportunity in both hands.

By the time Teresa left, Evelina was already in the habit of coming to the airport. She came perhaps once a month, especially on quiet weekdays, in the evening, sometimes still in her tour-guide uniform. The only person who knew about her habit was Jorge himself. She liked coming even without anyone to wave off, perhaps more so. She liked having time to watch the families, the kids in their Brazil-made chanclas running and chasing each other around the chairs and tables like these two little girls about six or seven here at the table besides hers. Round the table they chased, now one way, now the other, the smaller one giggling helplessly. She liked it so much she sometimes skipped going over to stand in the departure area, though she liked it there, too, watching the travellers being hugged.

But her best bit, secretly, was her own private regreso, coming back into the city after her airport coffee. This she liked the most. Sitting at the airport and then coming home again. She liked swooping her car into the fast lane, nearly empty at this hour, and then up the steep ramp and down her own avenida. She liked that feeling of coming back into her tiny flat, up the three flights of concrete steps that the janitor washed at five every evening, and opening the door onto her two neat rooms with everything standing exactly where she had left it. Even if that was just a few hours ago and no one could possibly have been in.

How grateful this journey made her for everything that she had here in this city. Which is why she didn’t get enough of visiting the airport, that heady feeling that the trip back home gave her every time.

Her family didn’t know about this habit of enjoying the arrivals hall or they might have come along on this mild Saturday evening, to help her get away, to give her the push she needed.

Her parents lived up country now, in the campo. They had held their send-off last weekend in her flat—her parents, her older brother Enrico who was a small pets vet, a couple of cousins from her mother’s side. They had made the four-hour round trip together in Enrico’s car. They had served oozing facturas from the panadería downstairs, and black tea with lemon, plus stronger stuff for those who wanted it, and they had talked about the repairs to Enrico’s new house and when he might start converting his extra garage into a practice. One of the cousins would be coming to stay for a while in Evelina’s flat, to have a long-expected holiday in the city, they said. They had talked only about solid things. As if by not saying much about Evelina’s leaving or about Jorge, the reason for her leaving, they could all pretend it wasn’t really taking place.

On the washed concrete steps they had said goodbye and their hugs were dry and unfussy. They were immigrant people, a little Welsh, a little Irish, and a lot of Buenos Aires. They set their faces to the future, which is to say, the future that was here, now, and solid.

From the beginning Evelina’s father had refused to say Jorge’s name. He had refused at first to meet him and when he did he refused at first to shake his hand. But he had never paid any of her few boyfriends even a morsel of attention.

‘His eyes want to undress you,’ he said of the first, Luciano, all of seventeen, still at school at the time. ‘It’s disgusting, arrojalo, get rid of him.’

Evelina had, but none of the others she brought home later had fared any better. Papá said he wanted to hit them all. In another day and age, he swore, he’d have taken a sword to them, pure and simple.

So this afternoon it was Evelina’s turn to sit in the airport waiting for a plane, on her own, without her family, but this time with a ticket in her purse. It was her turn to begin a new phase, in North America, in New York, a new phase to go with the new century, a chance to explore a new life with Jorge her fiancé, her energetic, open-hearted Jorge who had gone on ahead to set things up.

Sitting in the departures coffee shop, smaller than the one downstairs, Evelina noticed for the first time the good view through the big window beside the check-in gates. Even from here she could see through the window a section of the runway and the lit-up planes criss-crossing like fireflies against the sky now darkening towards evening.

Next time she’s here, she told herself, she’ll go over to the window to take a longer look. There was a shiny rail to lean on. There were people right now leaning on it, looking out, pointing, their dark profiles stamped on the glass. But then she remembered there wouldn’t be a next time and she had to put down her coffee, her hands trembled so.

The bag of toiletries and warm clothes she had packed stood beside her. She kept her leg pressed against the bag and her handbag pressed between her feet. Their box crates had gone ahead. For the air-trip itself she hadn’t known what to pack. What do you pack when you are changing continents, setting out to make a new life in New York with your beloved, your prometido? You could pack everything, or you could pack only your most special things that you wouldn’t want to send in a crate.

When her alarm rang this morning, she couldn’t find anything special enough to take along, nothing anyway that was small enough to carry, so she packed just this compact bag and in the end put in the wind-up alarm clock itself, on top, wrapped in a hanky. Couldn’t do harm, to start a new life with a reliable alarm clock.

As for the box crates, filling them had been like filling bags for charity, piling in stuff you never expected to see again. Even now, a few weeks on, she could barely remember the contents, Jorge’s kitchenware, yes, with the special block of knives, a needlepoint picture of snowy mountains done by his late mother as a young woman, also a few old pieces of furniture, hand-me-down stuff dry and cracked from standing long years in the sunshine in relatives’ apartments.

Old stuff for a new country—to her it didn’t make sense but Jorge insisted. It would cost the earth, he said, beginning a new home in New York from scratch.

Evelina wished Jorge was here now to give the encouragement his bright face always sparked in her, not that she ever let on. She didn’t want to raise second thoughts in his mind. She didn’t want him to know how scared she could get. With his big voice, his big muscles, his strong stride—nothing gave him a way of understanding this tremble now in her hands.

Perhaps it wasn’t wise for him to have gone ahead, she thought, though she had pressed him to go, so that he’d believe in her. It wasn’t wise, too, that she hadn’t yet let out her flat, her little home in the big city with its panadería downstairs and the outdoors gym painted in rainbow colours across the street. Would she, would they, be able to find anything so well-set-up in New York?

Right now Jorge was staying in some cheap hotel trying to find them a new home. They’d talked through every detail. He’d said he’d get in touch as soon as something worked out but he hadn’t yet called. She wished he’d called. She told herself he was waiting for her—waiting for this plane out there now on the runway, waiting for her to arrive in it, to come to New York to be with him and make a new home. She knew he would tell her everything then.

Home! Evelina looked around at the familiar purple sky beyond the window, and, closer at hand, the children in their flip-flop chanclas, two small boys this time kicking an empty drink carton back and forth, the little girls had disappeared. She looked at the shiny stickers of saints on the menu board over the coffee machine, and the two old men in crisp polo shirts talking at the exit, gesticulating just the same as they would meeting in a park in town.

Already these things were starting to look flat, two-dimensional and flat, as though they were already receding from view. Soon, within an hour or so, they would be pushed into the far distance by the whoosh of the aircraft, and then, tomorrow, by Jorge and his dreams, Jorge whom she really liked and thought she could soon, very soon, begin to love.

Jorge, she thought, and saw him sitting again in front of her with his hair tumbling over his forehead just as he had sat right there across the table at this exact coffee place those weeks ago at this exact time, give or take, the two icy red aperitivos standing untouched between them. He had bought them como una celebración, he said, to mark the start of their big adventure together.

Jorge’s pale eyes in his bronze face searching hers for some sign of reassurance, she could feel the pull in them, and she had told herself silently sitting there with her hand in his that she would see him again soon, in only a couple of months, seven or so weeks, though it felt a lot longer. And she had wished, still silently, it didn’t feel so long.

‘The planes for North America always leave around now, in the evening,’ he had told her, following her eyes watching the departure boards. ‘So that when you arrive es un nuevo día, the start of a new day.’

He had been making conversation, she could tell, thinking she knew these facts, but she hadn’t really known these things. She knew nothing. She worked in tourism but she had never yet left the country, not in her whole life, not once.

All she did know was that every day around nightfall, wherever she was, she felt a pull to go home so strong it upset her to resist it. She had felt the pull then waiting in this café with him. She felt it now.

But how could she have told him this? It would have sounded like doubt. It would have given him second thoughts. Yet all she wanted right now, today, even on this day of her departure, was to be in her flat and draw the curtains and scrunch up in a corner of her armchair with a cup of something warm. She thought of her armchair, the red one her mother had given her, the armchair that right now, unbelievably, was making its way across the sea squeezed in a crate alongside Jorge’s stuff.

‘Now promise me,’ he had urged that evening, his forehead shining like a lamp. ‘When the day arrives, just lock up the flat, and come. We’ve sent everything ahead that we need. I’ll be at the other end, remember, waiting for you. I’ll take you back to our apartamento, the one I’ll have got for us. We will start our new life. We’ll marry as soon as. I’ll begin straightaway to get our paperwork in order.’

And Evelina had waved him off, watching him descend down the long escalator, blowing kisses, till all she could see was his waving hand, and then, nothing. She had stood a while longer, in case he popped back into view. It was like him to step back, to give one last kiss, one last wave. But he hadn’t. So, when she was sure he was gone, she had slipped down to the café in arrivals and ordered herself a coffee. Her mouth had been dry from something she couldn’t place, though she knew it wasn’t sadness.

Evelina now bought a second coffee, a takeaway, and wondered about going downstairs for a while, to the arrivals hall. It was still ages before the flight. But then she sat down once more at the same table in the seating area, and pushed her used cup and saucer over to the edge, to make room. She sipped her coffee and looked around at all the familiar things, the stickers of the saints, the stainless steel bar, the children in their chanclas kicking and running. No one seemed to notice she hadn’t paid the drink-in extra. No one bothered about her sitting here at all.

20:30

Evelina checked her watch and tucked her chin deeper into her cretonne scarf. The sky beyond the viewing window was dark now and the evening cool settling in, even here in this air-conditioned space, but there was still plenty of time. Coming to the airport so early she had left plenty of time. She had shifted now from the departures coffee shop to a row of angled chairs alongside it. There was more than enough time still to go through security and buy a bottle of water and an eye-mask at the other end, as Jorge had instructed.

‘On the plane you make your own refugio, your own night capsule,’ he had said. ‘You tuck up in your seat and pull your blanket tight and close your eyes, and then, before you know it, you’ve arrived, you’re there.’

‘I know you,’ he’d also said, just before he left, swallowing his aperitivo in one gulp and glaring in that unblinking way he had when he was concentrating. ‘Don’t sit around and think or you’ll never be able to get away. Take your bag and walk straight through to the gates.’

Pressing her legs together and pulling her coat hem to her knees—her coat against the New York winter—Evelina tried now to bring his face into the very centre of her memory, to hold his image there so she could believe again in everything he had told her, in her new life in New York together with her handsome, savvy fiancé, believe in the restaurant business he would set up there, in a city full of restaurants.

But though he had sat across that table only a month or so ago the main thing she remembered was the pale eyes burning in his tanned face, that and what he said about the nuevo día.

When she arrives it will be the start of a new day.

Easier was detail from further back, the funny way his curly hair blew across his forehead when they went out cycling on Sundays, and their picnics in parks all over the city, and the food he liked to prepare, the curried eggs and spicy beef salads that were his speciality, the plastic dishes of food spread out along with his metal mate pot on her printed cloth on the grass.

She remembered their first date, at a rival steak restaurant to his, away from the centre, and the lovely loose feeling in her limbs that his energetic talk gave her, the pictures he painted of hiking in Patagonia, and seeing a mountain leopard, and then his dream of setting up a steak restaurant on 5th Avenue. These details felt like just days ago.

Clearest was the very first time of course, that startling and magical day when they had first met. There he had stood at the city event for young entrepreneurs, talking and making gestures with his big arms. She had worked through the exhibition hall looking for him, trawling up and down the aisles, and found him at last standing beside a poster that showed a steak jugoso in gleaming close-up, handing out leaflets, his fine wide face shining like a bronze mask.

Earlier, she had been at her post at the exhibition hall entrance just beyond the sliding doors and he had passed her. She was in her brown and orange tourist-board uniform checking nametags and handing out convention maps. She had given him a map and he had been the only one to say gracias, politely, looking her in the eye.

She found his stall by remembering the number on his tag. For her whole break she stood and looked at him from beside a pillar. She had never seen anyone with so open a face, so confident and shining a look, the kind of face you’d travel halfway across the world to see again.

On his way out he caught her eye for a second time and she smiled.

‘I saw your talk,’ she said.

He wrote her number on the company card she gave him and called the very next morning, just before nine.

Their first date was that Friday and they had got to know each other quickly after that. He had taken her to film festivals all over the city to see the old Argentinian films, BA a la vista, Rápido, La casa del ángel. She liked the dusty smells of the art house cinemas. She had only ever gone to big movie theatres before, with Enrico and his friends.

When Jorge proposed he had taken her back to the exhibition hall entrance, to the exact spot where she had stood and given him her number. It was a windy day and old leaflets and other rubbish bowled about their feet.

Later, he said he’d invited a saxophonist friend to come and play them background music from Rápido there on the steps but the guy hadn’t shown up. Who knows why? Jorge shrugged. Perhaps he hadn’t given him enough money for the cab.

But it hadn’t bothered her. She had her ring, she had his declaración. She assured him she preferred a proposal involving just the two people themselves.

Her father was more scornful and probably she shouldn’t have told him. It wasn’t his business. And yet she had blurted it out, there at her send-off party, the dulce de leche squeezing out of the pastry in his hand. And straightaway of course he harrumphed something about young men who thought too much about their grooming and too little about their bank balance. Which was unfair, she knew.

But she’d kept quiet, she’d said nothing in Jorge’s defence. She’d merely turned her eyes away from Papá eating his oozing factura and remembered the Chinese burns he used to give her and Enrico as children, when they were naughty.

‘See how much you want to stick to your silliness,’ he’d say, wringing their arms like a rag, twisting harder if they squeaked.

‘People go to New York and become anything they want, dancers, directors, professors, even princesses,’ Jorge had said those weeks ago over their untouched aperitivos. ‘It doesn’t matter if you come from los confines de la tierra, New York makes dreams come true.’

‘Sueños,’ he had said, cupping one hand like a scale. ‘Realidad,’ he had added, holding up the other.

She had looked hard then into his pale eyes. She saw in them excitement and hope. She saw the shape of the New York skyline. She would have liked to see something more, a little fear perhaps, so they could talk about that together. But Jorge’s eyes were the eyes of a man who would forge ahead and press on regardless of what setbacks he might meet, who would build his dreams in the streets of New York even if he didn’t have an Evelina to support him.

She jumped up now in a sudden impulse of horror, her coat falling to the ground. Jorge forging on without her, she couldn’t bear to think of it. She must go through with this now, fly away or else! Or these extremities of the earth would swallow her up. Jorge had the power to save her. Jorge would fold her in his arms and make new things possible. He had hope enough for two. Her chance lay in his hands, no, in his hands and her hands. Tomorrow morning she would be with him, pressed to his side, travelling with him on the subway into the heart of New York. But getting there depended on her, on getting herself on that flight. That was it with fretting. She could lose everything this way. Her chance lay here in her hands.

She picked up her bags and saw there was still time, un poco, a bit of time. She checked her watch against the digital clock on the departures board and made her way over to the viewing window. She wanted one last look at the familiar sky, the familiar line of hills still discernible above the distant city, the planes with their illuminated windows ascending and descending. If she put it off now, she would not see it again for years.

21:00

The tannoy announced that the flight gate was open. Evelina turned from the viewing window and saw the clear bubble of the telephone booth on the near wall. She didn’t want to see the booth but once she had seen it she couldn’t forget it. One last thing she really had to do, this is what it was telling her.

Jorge hadn’t called though he’d said he would, so now she would call him. Surprise, surprise, she would make a joke of it, laughing lightly. Sorpresa, little did you think! At the airport, where else? Just to say—this time tomorrow, our nuevo día, we’ll be on our way home, beginning our new life together.

But what if there was no home, no new apartamento? What if their papers had been refused? She’d heard nothing. She put down her bags at the booth and checked the slip in her passport, the numbers he had given her, first his friend in the steakhouse business, and then his father’s colleague’s nephew. He’d be staying with either the one or the other, whoever had space.

‘Don’t call me, I’ll call you,’ he’d said. ‘For a few days I won’t have a phone.’

But he hadn’t called. And it was weeks, not days. She didn’t doubt him but still he hadn’t called. Evelina felt suddenly empty, cavernous. She felt the great dark seas that separated them wash over her heart.

No, she thought, no, and reached suddenly for the back of the chair closest to her, the rough woollen shoulder of the gentleman sitting in it.

Somebody then took her arm and guided her to a nearby counter.

‘You look very pale,’ the attendant at the counter said. ‘Look, why not give me your bags? I can help you to your gate.’

‘Let me take a moment,’ Evelina heard herself say in a composed voice. The cold steel edge of the counter pressing into her palm gave her comfort. It was like holding onto a raft.

‘I was trying to make a call but somehow it didn’t work,’ she said. ‘I didn’t get through. Maybe I don’t have the right number.’

21:30

The last call for her flight, for the second time they were calling out her name, Evelina, Evelina, as if they were welcoming her. She was on her way, she really was. She had worked in the travel business and now she was a traveller, too. She had made it through security and passport control. Her documents were here in her left hand, slid inside her travel company’s own white plastic folder. The folder was her goodbye present from her colleagues, that and a smart purse containing a nail-care kit. Had she remembered to pack the purse? She wanted to check but as she made to bend down she caught sight of the gate number there ahead of her, silver numbers on a blue screen, and a flight attendant waving. There was no one else about, theirs was the last plane out, she was the last passenger to arrive. She was almost at the gate. Now it was just the flight bridge to go and then they’d seal the great aeroplane door behind her. She really was on her way. Tomorrow she’d be with Jorge in New York, riding the subway with him as they somehow had never done here in their own city, pressing herself to his side.

Jorge, she could see his pale eyes burning in his bronze face—his face like a mask sometimes, polished, shining. She tried to imagine him waving at her like the flight attendant was waving, waving across the great dark seas that stretched between here and New York. She made herself see the moving waters as if from high up in the dark sky, from the plane she would soon be flying in, soaring above those black waves she had so recently felt curling around her heart. From here up high, her seatbelt pressing into her lap, she could see, peering down, the stars reflected in the dark waters, and the lights of the city shimmering at their edge, and, though it was still night, the black arrow of the plane’s shadow rushing across the moving, churning sea.

On David Malouf

On David Malouf Sergius Seeks Bacchus

Sergius Seeks Bacchus Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva was born in 1892. She left Russia in 1922, returned in 1939, and was to die two years later. She is celebrated as one of the greatest Russian poets of the Twentieth Century. Her first book was entitled Evening Album.

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva was born in 1892. She left Russia in 1922, returned in 1939, and was to die two years later. She is celebrated as one of the greatest Russian poets of the Twentieth Century. Her first book was entitled Evening Album. Paul Magee is author of Stone Postcard (2014), Cube Root of Book (2006) and the prose ethnography From Here to Tierra del Fuego (2000). Paul majored in Russian and Classical languages, and has published translations of Vergil, Catullus, Horace and Ovid. He is currently working on a third book of poems, ‘The Collection of Space’. Paul is Associate Professor of Poetry at the University of Canberra.

Paul Magee is author of Stone Postcard (2014), Cube Root of Book (2006) and the prose ethnography From Here to Tierra del Fuego (2000). Paul majored in Russian and Classical languages, and has published translations of Vergil, Catullus, Horace and Ovid. He is currently working on a third book of poems, ‘The Collection of Space’. Paul is Associate Professor of Poetry at the University of Canberra. Paul de Brancion is the author of about fifteen novels and poems. He is regularly involved in transversal artistic projects, with contemporary art centres or music composers (T. Pécou, J-L. Petit, G. Cagnard, N. Prost, …). He lives and works between Paris, Corsica and Nantes. Where he organises and presents “Les Rendez-vous du Bois Chevalier”, annual events dedicated to literature, science and poetry.

Paul de Brancion is the author of about fifteen novels and poems. He is regularly involved in transversal artistic projects, with contemporary art centres or music composers (T. Pécou, J-L. Petit, G. Cagnard, N. Prost, …). He lives and works between Paris, Corsica and Nantes. Where he organises and presents “Les Rendez-vous du Bois Chevalier”, annual events dedicated to literature, science and poetry. Formerly a music educator and writer, Elaine Lewis created the Australian Bookshop in Paris in 1996. She met poet Jacques Rancourt and began translating for the Franco-anglais Poetry Festival. Her book

Formerly a music educator and writer, Elaine Lewis created the Australian Bookshop in Paris in 1996. She met poet Jacques Rancourt and began translating for the Franco-anglais Poetry Festival. Her book  Lucida Intervalla

Lucida Intervalla Calenture

Calenture Jill Jones has published eleven books of poetry, and a number of chapbooks. The most recent are Viva La Real with UQP, Brink, The Leaves Are My Sisters, The Beautiful Anxiety, which won the Victorian Premier’s Prize for Poetry in 2015, and Breaking the Days, which was shortlisted for the 2017 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. Her work is represented in major anthologies including the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature, Ed. Nicholas Jose and The Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry. In 2014 she was poet-in-residence at Stockholm University. She is a member of the J.M.Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice, University of Adelaide.

Jill Jones has published eleven books of poetry, and a number of chapbooks. The most recent are Viva La Real with UQP, Brink, The Leaves Are My Sisters, The Beautiful Anxiety, which won the Victorian Premier’s Prize for Poetry in 2015, and Breaking the Days, which was shortlisted for the 2017 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. Her work is represented in major anthologies including the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature, Ed. Nicholas Jose and The Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry. In 2014 she was poet-in-residence at Stockholm University. She is a member of the J.M.Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice, University of Adelaide. The short story of you and I

The short story of you and I The Red Pearl and Other Stories

The Red Pearl and Other Stories Coach Fitz

Coach Fitz Imminence

Imminence The Burning Elephant

The Burning Elephant Autobiochemistry

Autobiochemistry Kavita Nandan recently moved to Sydney and teaches creative writing and literature at Macquarie University. Her first novel Home after Dark was published in 2014. She is the editor of Stolen Worlds: Fijiindian Fragments. Her short stories have been published in Transnational Literature, The Island Review and Landfall.

Kavita Nandan recently moved to Sydney and teaches creative writing and literature at Macquarie University. Her first novel Home after Dark was published in 2014. She is the editor of Stolen Worlds: Fijiindian Fragments. Her short stories have been published in Transnational Literature, The Island Review and Landfall. AXIS Book I: ‘Areal’

AXIS Book I: ‘Areal’

Claire Albrecht is writing her PhD in Poetry at the University of Newcastle. Her current work investigates the connections between poetry/photography and sex/politics. Claire’s poems appear in Cordite Poetry Review, Overland Literary Journal, Plumwood Mountain, The Suburban Review and elsewhere. Her manuscript sediment was shortlisted for the 2018 Subbed In chapbook prize, and the poem ‘mindfulness’ won the Secret Spaces prize. Her debut chapbook

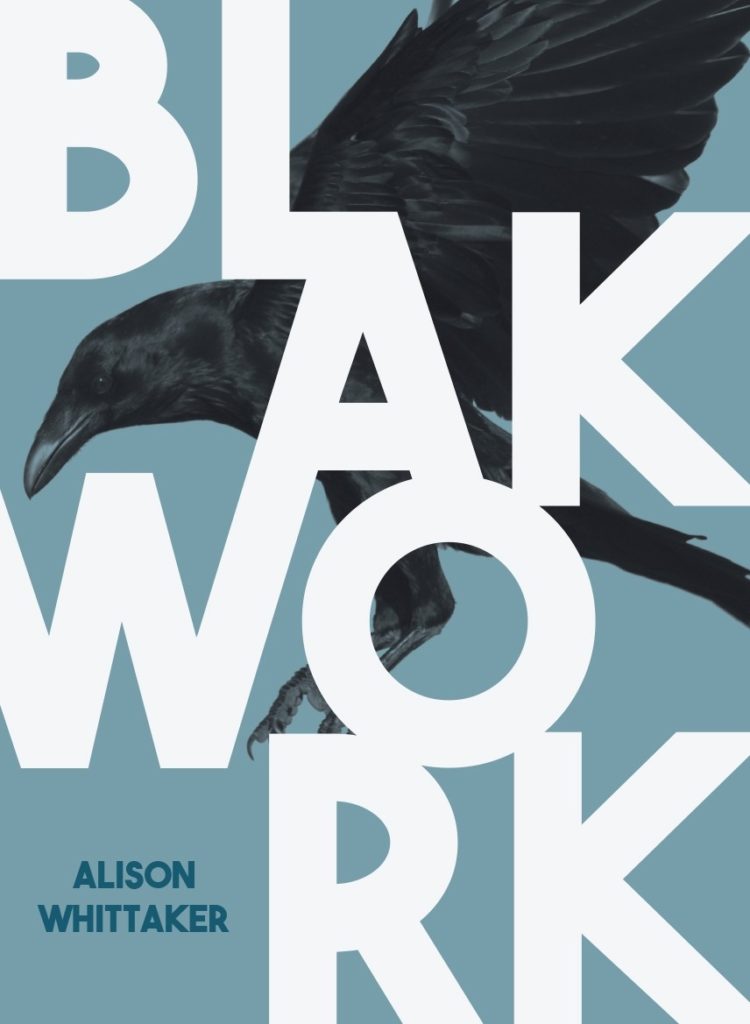

Claire Albrecht is writing her PhD in Poetry at the University of Newcastle. Her current work investigates the connections between poetry/photography and sex/politics. Claire’s poems appear in Cordite Poetry Review, Overland Literary Journal, Plumwood Mountain, The Suburban Review and elsewhere. Her manuscript sediment was shortlisted for the 2018 Subbed In chapbook prize, and the poem ‘mindfulness’ won the Secret Spaces prize. Her debut chapbook  Autumn Royal is a poet and researcher. Autumn’s poetry and criticism have appeared in publications such as Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry, Overland Literary Journal, Southerly Journal and TEXT Journal. She is interviews editor for Cordite Poetry Review and author of the poetry collection She Woke & Rose. Autumn’s second collection of poetry is forthcoming with Giramondo Publishing.

Autumn Royal is a poet and researcher. Autumn’s poetry and criticism have appeared in publications such as Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry, Overland Literary Journal, Southerly Journal and TEXT Journal. She is interviews editor for Cordite Poetry Review and author of the poetry collection She Woke & Rose. Autumn’s second collection of poetry is forthcoming with Giramondo Publishing. The Book of Thistles

The Book of Thistles  Rain Birds

Rain Birds

David Adès

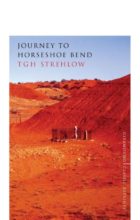

David Adès Journey to Horseshoe Bend

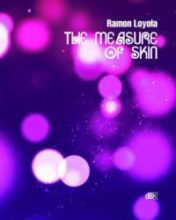

Journey to Horseshoe Bend The Measure of Skin

The Measure of Skin

Richard James Allen

Richard James Allen

ALICE WHITMORE is the Pushcart Prize and Mascara Avant-garde Award-nominated translator of Mariana Dimópulos’s All My Goodbyes and Guillermo Fadanelli’s See You at Breakfast?, as well as a number of poetry, short fiction and essay selections. She is the translations editor for Cordite Poetry Review and an assistant editor for The AALITRA Review. Her translation of Mariana Dimópulos’s Imminence is forthcoming in 2019 from Giramondo Publishing.

ALICE WHITMORE is the Pushcart Prize and Mascara Avant-garde Award-nominated translator of Mariana Dimópulos’s All My Goodbyes and Guillermo Fadanelli’s See You at Breakfast?, as well as a number of poetry, short fiction and essay selections. She is the translations editor for Cordite Poetry Review and an assistant editor for The AALITRA Review. Her translation of Mariana Dimópulos’s Imminence is forthcoming in 2019 from Giramondo Publishing.

Elleke Boehmer was born in Durban and lives in Oxford. She is the author of five novels including Screens against the Sky (1990), Bloodlines (2000), Nile Baby (2008), and The Shouting in the Dark (2015). Screens against the Sky was short-listed for the David Higham Prize, and Bloodlines for the Sanlam Prize. The Shouting in the Dark was long-listed for the Sunday Times prize (South Africa). She is the author and editor of over fifteen other books, including Stories of Women (2005), Postcolonial Poetics (2018), and a widely translated biography of Nelson Mandela (2008). Indian Arrivals 1870-1915: Networks of British Empire (2015) was the winner of the biennial ESSE 2015-16 Prize. South, North is her second collection of short stories, following Sharmilla, and other Portraits (2010). The Australian edition of The Shouting in the Dark, together with other writing about the global south, is coming out from UWAP in early 2019.

Elleke Boehmer was born in Durban and lives in Oxford. She is the author of five novels including Screens against the Sky (1990), Bloodlines (2000), Nile Baby (2008), and The Shouting in the Dark (2015). Screens against the Sky was short-listed for the David Higham Prize, and Bloodlines for the Sanlam Prize. The Shouting in the Dark was long-listed for the Sunday Times prize (South Africa). She is the author and editor of over fifteen other books, including Stories of Women (2005), Postcolonial Poetics (2018), and a widely translated biography of Nelson Mandela (2008). Indian Arrivals 1870-1915: Networks of British Empire (2015) was the winner of the biennial ESSE 2015-16 Prize. South, North is her second collection of short stories, following Sharmilla, and other Portraits (2010). The Australian edition of The Shouting in the Dark, together with other writing about the global south, is coming out from UWAP in early 2019. No Friend But The Mountains

No Friend But The Mountains

Mosaics from the Map

Mosaics from the Map Dark Matters

Dark Matters Chris Andrews’ latest translation, Melodrome (2018), published here in Australia as part of Giramondo’s Southern Latitudes Series, is a novella by the Argentine science fiction writer, Marcelo Cohen (1951-). The author of 14 novels, 5 story collections, many essays and countless translations, Cohen is already well-known in the Spanish-speaking world. He lived in Spain from 1975 to 1996, during the dictatorship in Argentina, and has been publishing fiction since the early 1980s.

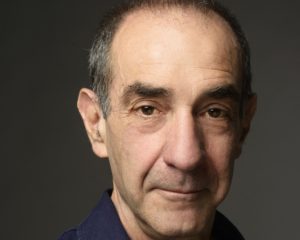

Chris Andrews’ latest translation, Melodrome (2018), published here in Australia as part of Giramondo’s Southern Latitudes Series, is a novella by the Argentine science fiction writer, Marcelo Cohen (1951-). The author of 14 novels, 5 story collections, many essays and countless translations, Cohen is already well-known in the Spanish-speaking world. He lived in Spain from 1975 to 1996, during the dictatorship in Argentina, and has been publishing fiction since the early 1980s. Marcelo Cohen (Buenos Aires, 1951) is a widely respected and highly innovative Argentinian novelist, who has invented a distinctively South American kind of speculative fiction. In an ambitious series of novels and stories he has constructed a future world, the Panoramic Delta, in which he imagines in detail a range of changes beyond those wrought directly by technology: political, cultural and emotional. One of the most agile stylists writing in Spanish today, he is also an internationally renowned translator, critic and editor. An fundamental name in Argentinian literature of the last two decades.’— Fernando Bogado, Radar‘

Marcelo Cohen (Buenos Aires, 1951) is a widely respected and highly innovative Argentinian novelist, who has invented a distinctively South American kind of speculative fiction. In an ambitious series of novels and stories he has constructed a future world, the Panoramic Delta, in which he imagines in detail a range of changes beyond those wrought directly by technology: political, cultural and emotional. One of the most agile stylists writing in Spanish today, he is also an internationally renowned translator, critic and editor. An fundamental name in Argentinian literature of the last two decades.’— Fernando Bogado, Radar‘ Thuy On is a freelance arts journalist and critic, who writes for a variety of publications including The Australian, The Age, The SMH, Books and Publishing and ArtsHub. She’s also the books editor of The Big Issue.

Thuy On is a freelance arts journalist and critic, who writes for a variety of publications including The Australian, The Age, The SMH, Books and Publishing and ArtsHub. She’s also the books editor of The Big Issue. Renga: 100 Poems

Renga: 100 Poems