May 6, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham

Edited and Introduced by Nathanael O’Reilly

UWA Publishing, 2017

ISBN 978-1-7425892-0-6

Reviewed by KATIE HANSORD

The significance, value, and breadth of Anna Wickham’s poetry extends beyond categories of nation and resists the limitations of such categories. The category of woman, however, is central to her poetics, as both a culturally ‘inferior’ and structurally imposed designation, and as a proud personally and politically conceptualised identity, and marks Wickham’s important and consistent feminist contribution to poetry. ‘As a woman I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman my country is the whole world’ (Three Guineas 197) are the words Virginia Woolf once chose to express this sense of solidarity with other women beyond national borders. Born Edith Alice Mary Harper in 1883, in London, Wickham lived in Australia from the ages of six to twenty, later living again in England, in Bloomsbury and Hampstead, as well as living in France, on Paris’ Left Bank. Wickham is noted to have taken her pen name from the Street in Brisbane on which she first promised her father to become a poet, and the early encouragement of her creativity was to be a seed which would grow and continue to bloom despite cultural bias and personal circumstance, including the opposition of her husband to her writing, and institutionalisation. She was connected with key modernist and lesbian modernist figures including Katherine Mansfield, and Natalie Clifford Barney, whose Salon she attended, becoming a member of Barney’s Académie des Femmes, and with whom she is noted to have ‘corresponded…for years, expressing passionate love and debating the role and problems of the woman artist’ (Feminist Companion 1162).

Wickham’s poetry represents a significant achievement within early twentieth century poetry and can be described as deeply concerned with an activist approach to issues of gender, class, sexuality, motherhood, and marriage. These are all issues that address inequalities still largely unresolved, although in many ways different and understood quite differently, today. These poems may be playful, experimental, self-conscious, and passionate poems that are varied but always conscious of their position and their place in terms of both political and poetic traditions and departures from them towards an imagined better world. In the previously unpublished poem ‘Hope and Sappho in the New Year,’ Wickham boldly suggests both lesbian and poetic desire and a class-conscious refusal of bourgeois devaluation as she asserts:

Let Justice be our mutual gift

Whose every prospect pleases

And do not mock my only shift

When you have three chemises

Then I will let your chains atone

For faults of comprehension-

Knowing you lived too long alone

In worlds of small dimension.

A refusal to accept such ‘worlds of small dimension’ reiterates the inclusion of emotional, psychological and structural disparities, as have frequently been noted in her previously published poem ‘Nervous Prostration’, in which she describes her husband as ‘a man of the Croydon class’ (New and Selected 19) and in which she plainly and honestly addresses the structural and emotional complexities of her heterosexual bourgeois marriage.

In poem ‘XX The Free Woman’ Wickham outlines a moral and intellectual approach to marriage for the woman who is free, writing:

What was not done on earth by incapacity

Of old, was promised for the life to be.

But I will build a heaven which shall prove

A lovelier paradise

To your brave mortal eyes

Than the eternal tranquil promise of the Good.

For freedom I will give perfected love,

For which you shall not pay in shelter or in food

For the work of my head and hands I will be

paid,

But I take no fee to be wedded, or to remain a

Maid.

Wickham’s poetry is notable for its balanced concision and depth as much as for the expansive, inclusive, intersectional approach it takes. I am using the term intersectional to refer here to an approach which is understanding of the interconnected nature of oppression in terms of gender, class, and sexuality, although it should be acknowledged that the poems do not tend to address issues of racism specifically.

New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham, edited and introduced by Nathanael O’Reilly, brings together for the first time in print a wide inclusion of previously unpublished poems, gathered from extensive research into Wickham’s archive at the British Library. Significantly, O’Reilly’s thoughtful and careful editorship of this collection restores Wickham’s original versions of the published poems included, as well as presenting the unpublished poems in their original style and punctuation, giving the reader a clearer sense of the poet’s intention and expression. One such example is the sparing use of full stops in the poems, suggesting again Wickham’s expansive, inclusive, and flowing mode that defies the limitations of ‘worlds of small dimension’. Until this publication, readers have not been able to access these poems in print, and the majority of Wickham’s poems, over one thousand, have not been in print. Sadly, some of her writing, including manuscripts and correspondence, was destroyed in a fire in 1943. This new collection includes one hundred previously published poems as well as one hundred and fifty previously unpublished poems, making it a substantial and impressive feat. Wickham’s published collections, now out of print, included Songs of John Oland (1911), The Contemplative Quarry (1915), The Man with the Hammer (1916) and The Little Old House (1921) and she had a wide reputation in the 1930s. This expanded collection of her poetry then, is to be warmly welcomed and applauded as a timely extension of the available poems of Anna Wickham, following on from the earlier publication in 1984 of The Writings of Anna Wickham Free Woman and Poet, edited and introduced by R.D. Smith, from Virago Press, and before that her Selected Poems, published in 1971 by Chatto & Windus, reflecting the renewed interest in Wickham during the women’s movement of the 1970s.

These previously unpublished poems give further insight into Wickham’s experimentation, variation of form and style, and poetic achievement. Jennifer Vaughn Jones’ A Poets Daring Life (2003) and Ann Vickery’s valuable work on Anna Wickham in Stressing the Modern (2007) as well as that of other Wickham scholars, may more easily be expanded upon by others with the publication of this new extensive collection of Wickham’s poetry. Although Wickham’s works are now much more critically recognised than has been the case in the past, it is to be hoped that the publication this new collection will go some way to further redressing what has tended to be seen as a baffling lack of critical attention for such an important poet. Equally importantly though, the publication of this collection opens out an expanded world of Wickham’s writings to all readers and lovers of poetry wanting to engage with a poetic voice that so eloquently and purposefully brings to the fore the issues of justice, equality, gender, and both the societal and personal freedoms that remain so crucial and relevant to readers today.

NOTES

Blain, Virginia, Patricia Clements and Isobel Grundy (Eds). The Feminist Companion to Literature in English, Batsford: London, 1990.

Vickery, Ann. Stressing the Modern, Salt, 2007

Wickham, Anna. The Writings of Anna Wickham Free Woman and Poet, Edited and introduced by R.D. Smith, Virago Press, 1984.

Wickham, Anna. New and Selected Poems of Anna Wickham, Edited and Introduced by Nathanael O’Reilly, UWAP, Crawley 2017.

Woolf, Virginia. Three Guineas. London: Hogarth Press, 1938.

KATIE HANSORD is a writer and researcher living in Melbourne. Her PhD thesis examines nineteenth century Australian women’s poetry and politics. Her work has been published in ALS, Hecate, and JASAL, as well as LOR Journal and Long Paddock (Southerly Journal).

March 22, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

The Lost Culavamsa: or the Unimportance of Being Earnest

The Lost Culavamsa: or the Unimportance of Being Earnest

about Aryan & Dravidian

a play, by Ernest Macintyre

Vigitha Yapa Publications (Colombo, Sri Lanka), 2018

ISBN 978-955-665-319-9

Reviewed by ADAM RAFFEL

In February 2016, in the best traditions of suburban amateur theatre, a group of Sydneysiders of Sri Lankan background performed a play called The Lost Culavamsa (pronounced choo-la-vam-sa) written and directed by fellow thespian and playwright Ernest Macintyre at the Lighthouse Theatre in the grounds of Macquarie University. I had the privilege of co-directing this play as Ernest Macintyre himself was in poor health at the time. I have known the playwright for over 40 years and I was happy to oblige. It was a delightful rewriting of Oscar Wilde’s witty comedy of manners, The Importance of Being Earnest, about late Victorian English snobbery transplanted to an equally snobbish colonial setting in British Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in the 1930s. Ernest Macintyre had created an enjoyable piece of comic theatre about mistaken identity while engaging the audience with deeper questions of ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’. Macintyre has re-imagined and re-worked Wilde’s play into a satire about the absurdity of racism and communal division. A play for our times and the universality of its theme won’t be lost on audiences who have never heard of Ceylon or Sri Lanka.

However Macintyre is showing a mirror to Sri Lankans in particular. Many of the intricacies and details of the dialogue of The Lost Culavamsa will resonate especially to Sri Lankan audiences just emerging from a 30 year civil war that concluded in 2009. It was nothing short of a national trauma for that island and its inhabitants. At the core of the war was what it is to be a Sri Lankan. The island’s 2500 year written history was deployed by nationalists to justify and push political agendas. The Culavamsa is an ancient Sinhalese chronicle somewhat like the Anglo Saxon Chronicle or Beowulf written in the about the same time in the 7th or 8th century AD, which was the later version of a more ancient Sinhalese chronicle called the Mahavamsa that chronicled the ancient history of the island from the 5th century BC. These were written in poetic form like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, part history part mythology, and were “weaponised” by nationalists where ancient battles were used as dramatic props in a very 20th and 21st century civil war. Viewed in this context The Lost Culavamsa can be seen as much needed comic relief for a war weary country with a core message of tolerance. Macintyre has deployed the best comic traditions of English theatre to communicate this message to audiences in general and to Sri Lankan audiences in particular. Ironically Macintyre uses the English language in this context not as a symbol of colonial oppression, which it was at one point in Sri Lanka’s history, but as a language of unity and of liberation from the tyranny of ethnic hatred and division. Macintyre shows that English can be a used as a link language between the communities in Sri Lanka, uniting them so they can share their stories. In other words English can be appropriated as a Sri Lankan language. So Macintyre sets his play in the late afternoon of the British Empire as a means to communicate to Sri Lankans how they once were and not to feel ashamed or nostalgic but to learn and accept that colonialism changed the country forever and in Lady Panabokka’s words (the character based on Lady Bracknell) “that humans go forward, not backwards and whether the British Empire lasts or not, it is a stage in the forward motion of civilization”.

These lines uttered by Lady Panabokka underline Macintyre’s view that history cannot be undone. Whether Sri Lankans like it or not colonialism was a historical reality and now forms an integral part of its history. Any attempt to wipe it out is not only futile but dangerous. It is a progressive view of independent Ceylon that drew upon the playwright’s own extensive experience in Sri Lankan theatre and the arts in the 1950s and 1960s. This was a period in the island’s history where artists, writers, dramatists, musicians, historians and architects of the English speaking elite (of which Macintyre and my parents were a part) were engaging with local Sinhalese and Tamil speaking artists in an attempt to construct a national “Sri Lankan” identity and vernacular culture that drew upon the best of European, Indian, other Asian and local Sri Lankan traditions. The milieu, in which Macintyre acted, directed and wrote in his youth and early adulthood still has a profound influence on his world view that a nation state consists of multiple nationalities, faiths and communities and should have a national artistic culture that draws upon its local multiple traditions while being nourished by international artistic influences including that of the country’s former colonial rulers. The fact that one can place Macintyre in the English / Australian theatrical tradition as well as in the Sri Lankan one is something that he is very comfortable with. An example of this is the first play he wrote in Australia in the 1970s called Let’s Give Them Curry a comedy about an immigrant Sri Lankan family in suburban Australia. Both Australia and Sri Lanka view that play as a part of their own theatrical repertoires. Unfortunately Let’s Give Them Curry was his first and only play that dealt with Australia. For in 1983 his world was turned upside down. The community he belonged to in Sri Lanka; the Tamils suffered a series of state sponsored pogroms where they and their property were systematically attacked by chauvinistic Sinhalese Buddhist mobs. Thousands were killed and the trajectory of the country changed forever. This affected Ernest Macintyre personally as he saw many close friends and family lose their lives and livelihoods. He used his vantage point in Australia to comment on the idiocy and futility of the endless cycle of violence in the land of his birth with a series of plays he wrote starting in 1984 and continuing to the present day. Macintyre drew upon his favourites of the Western theatrical canon – Sophocles, Shakespeare, Brecht, Beckett, Arthur Miller, Edward Albee, Shaw and Oscar Wilde to write satires, tragedies and comedies dealing with the subject of communal violence in Sri Lanka in order to have a wider conversation about identity. The Lost Culavamsa is the latest in that series.

The Ceylonese (Sri Lankan) characters in The Lost Culavamsa are a carbon copy of Wilde’s English characters in The Importance of Being Earnest. These Ceylonese characters also speak an English redolent of the Edwardian England of Wilde himself. They illustrate the extent of British influence amongst the local Ceylonese elite in the 1930s. These elites were loyal to the British Empire where the sun was about to set very rapidly. The Ceylonese upper bourgeoisie, however, thought that their world of tea, whiskey, cricket, bridge and tennis would last forever. Many of them thought that they were brown Englishmen and women consuming Shakespeare, Milton and Dickens treating these icons of English high art as their own and dismissing with contempt any attempt by local Sinhalese or Tamil speakers to re-write and translate works from the European literary canon. To them Ceylon was a little England where the general population was, at best, an endless supply of domestic servants and workers to toil in their estates and at worst something inconvenient to put up with. This exchange between Lady Muriel Panabokka and James Keethaponcalan (mimicking the famous ‘interrogation’ scene in the Importance of Being Earnest where Lady Bracknell interrogates Jack Worthing as to his suitability to marry her niece Gwendolyn Fairfax) illustrates the point:

Lady Panabokka: A formal proposal of marriage shall be conducted properly in the presence of the parents of both parties, Sir Desmond and I and your two parents. However, that is not on the cards, at all, till my preliminary investigations are satisfactorily completed.

(Lady Panabokka sits)

Ernest, please be seated. Let me begin.

James: I prefer to stand.

(He stands facing Lady Panabokka. She takes out a notebook and a pencil from her bag)

Lady Panabokka: Some questions I have had prepared for some time. In fact this set of questions has evolved, at our social level, as a standard format of precaution, for our daughters and our social level. First, are you in any way involved in this so called peaceful movement for eventual independence from the British?

James: It doesn’t bother me, Lady Panabokka, I’m happy with the status quo, the British Empire……

Lady Panabokka: Excellent.

James: But I have been made to think about it, sometimes…

Lady Panabokka: What is there to think about it?

James: That we have to lead….. double lives…..

Lady Panabokka: What is that?

James: Like, my name is Ernest, but also Keethaponcalan

Lady Panabokka: So?

James: Ernest is from the British Empire, Keethaponcalan from the native Tamil culture, something like a …a double life…..

Lady Panabokka: Where do you get such confused ideas from?

James: From a scholar I know well……I was told that sometime or other the British Empire will be no more and we will all have to think of our own historical origins….

Lady Panabokka: How far back do we have to go? To when we were apes? Before we were Sinhalese or Tamil we were all apes, hanging on the same tree and chattering the same sounds! Tell your scholar, obsessed with the past, that humans go forward, not backwards and whether the British Empire lasts or not, it is a stage in the forward motion of civilization….

James: Never thought of it like that….

Lady Panabokka: So many things you “never thought of it like that”. And there is the practical problem of the Indians. My husband Sir Desmond thinks our only real protection from the Indians is to be in the firm embrace of the British Empire. And the Indian idea that we are of the same stock was put to the test when Sir Desmond had to visit India recently for a Bridge tournament and found that the supposedly bridging language between them and us, English, was subjected to such outlandish accents, that the game took sudden wayward turns, the way the Indian accents misled the Ceylonese.

James: Yes, I have heard that they don’t speak English like us.

Lady Panabokka: Now, what may be, a related question. Do you speak Sinhalese?

James: I’m well educated in Tamil and speak it fluently

Lady Panabokka: That is an unnecessary distraction, I asked you about Sin Halese

James: Sin Halese……well, sort of, yes, to deal with the general population and…..

Lady Panabokka: That’s why I asked, because (with a sigh) the general population will always be with us. There is no harm, though, in knowing some Sin Halese oneself, for its own sake, but one must not carry it too far.

James: Too far?

Lady Panabokka: Yes, I don’t think you have heard of this man called Sara Chch Andra, a strange name even for a Sin Halese….

James: No, I have not heard….

Lady Panabokka: I’m glad. He should remain unheard of

James: Why?

Lady Panabokka: You know, Oscar Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest”?

James: I love it, I played Lady Bracknell in school!

Lady Panabokka: It is one of our beloved plays, and this man, Sara Chch Andra has debased it by re- writing it, in Sin Halese, as “Hangi Hora” [Hidden Thief], whatever that means!

James: Really?

Lady Panabokka: Yes, I got it from Professor Lyn Ludowyk. Lyn was at Sir Herbert Stanley’s garden party at Queens House yesterday, and he actually spoke about it approvingly. Sometimes I really can’t understand Lyn….why can’t these people write their own plays and not rewrite ours!

The comic irony of the line “why can’t these people write their own plays and not rewrite ours” won’t be lost on a Sri Lankan audience. Lady Panabokka who is an English speaking Sinhalese sees no problem with The Importance of Being Earnest as “her play” and by “these people” she means the Sinhalese speaking writers who should be writing “their own plays”. She sees herself as quintessentially English who would have graciously accepted the fact that she would not be allowed into the Colombo Club which was an exclusively whites-only club for English civil servants and administrators. Lady Panabokka, like Lady Bracknell, sees the world as a hierarchy where everyone has their allocated place, which they should accept with grace and dignity. As Macintyre says in his introduction to his play:

So Lady Panabokka establishes early in the play, that … like Lady Bracknell, … her belief that what matters in life is social status and class. Even race maybe ignored where class prevails as it happens with many Colombo “upper class” young people, Sinhalese and Tamils …

Lady Panabokka who “supervises” this whole improbable comedy is the most identifiable of Oscar Wilde’s characters, the famous Lady Bracknell. She is transplanted. The whole plot, except for the meaning of ethnicity in Lanka which makes it a different play, is transplanted Oscar Wilde, with the colours, hues and texture of the plant growing naturally from the soil of British Ceylon.

In the final Third Act of The Importance of Being Earnest the relatively minor character of Miss Prism exposes the real identities of Algernon Moncrieff and Jack Worthing to their respective love interests Cecily Cardew and Gwendolyn Fairfax. In Wilde’s play Miss Prism locates the lost handbag in which she left the baby Jack Worthing twenty years earlier. In The Lost Culavamsa the point of departure from Wilde lies in how Pamela Mendivitharna unveils the identities of Danton Walgampaya and James Keethaponcalan to their respective love interests Sridevi Kadirgamanathan and Gwendolyn Panabokka.

Macintyre has transformed Miss Prism’s character Pamela Mendivitharna to a major role on a par with Lady Panabokka (the Lady Bracknell character). Pamela is a scholar who lost the baby James in Colombo in a malla (a shopping bag made of treated palm leaves) together with a copy of the Culavamsa. She was a governess to this baby James whose biological mother was Lady Muriel Panabokka’s sister and also Danton Walgampaya’s mother who was Sinhalese (Aryan). Pamela lived with baby James’s parents while pursuing her research into the ancient history of the Aryans and Dravidians in Sri Lanka, which was also a popular pastime of British civil servants and orientalists in Ceylon during that period. Baby James was found by a Jaffna Tamil couple Sir Kandiah and Lady Keethaponcalan and adopted him as their own in a Tamil (Dravidian) environment. Pamela eventually traced baby James to Jaffna and found employment with the Keethaponcalans as James’s nanny. As Macintyre says in his introduction:

Why in this story is there a copy of the Culavamsa … also inside the malla with the baby? The Culavamsa’s part in the play is to link up this story with, arguably, character as big and important to the story … Pamela Mendivitharna, the lady who was responsible for the baby in her paid care …

While this baby [James] born into a Sinhalese family grows up as a Tamil, Pamela Mendivitharna … begins to doubt the well-held belief of the time [1930s] … that the ethnicities of Ceylon [Sri Lanka] resulted from North Indian Aryans settling in the island and South Indian Dravidians coming to the island as a different “race”.

The final denouement of the play ends just as Wilde’s. The only difference being Pamela’s explanation to the audience that the two blood brothers were brought up in different environments and each displaying the characteristics of the environment in which they were brought up. Her study of the Culavamsa was crucial in her realisation that “our ethnicities reveal social attributes, not biological differences.” This is where Macintyre uses Wilde’s structure to expose the fallacy of ‘race’ as an exclusively biological characteristic. The ancient chroniclers and poets of the Culavamsa mention different groups or tribes or nationalities but they could not have had any idea of the very modern and European scientific and biological concept of ‘race’. Macintyre’s play is set in the 1930s, a time when Eugenics and the pseudo-science of Social Darwinism were prevalent in Europe and United States in order to legitimise the odious narrative of white European supremacy. This sort of thinking also influenced some South Asian nationalists during that time as they appropriated these European pseudo-sciences to construct their equally odious narratives of their own national origins. Later on this would have deadly consequences in the rise of fascism and communal violence in Europe and Asia.

Macintyre, however, never loses focus that this play is essentially a romantic comedy. His close following of Wilde’s structure and characters in The Importance of Being Earnest makes viewing and reading Ernest Macintyre’s The Lost Culavamsa an enjoyable experience. Macintyre has transplanted all of Wilde’s minor characters including Reverend Chasuble who is re-created as Reverend Abraham Pachamuttu, the servant Lane as Seyadu Suleiman and the butler Merriman as Albert. As with all great comedies whether it be the films of Charlie Chaplin or Luis Bunuel or the plays of Oscar Wilde or George Bernard Shaw there is always an undercurrent of seriousness and even tragedy. The Lost Culavamsa is, in my mind, no different.

ADAM RAFFEL is a Sydney poet and writer.

February 28, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Eunice Andrada is a Filipina poet, journalist, lyricist and teaching artist based in Sydney. Featured in the Guardian, CNN International, ABC News and other media, she has performed her poetry in diverse international stages, from the Sydney Opera House and the deserts of Alice Springs to the United Nations Climate Negotiations in Paris. During a residency in Canada’s prestigious Banff Centre, she collaborated with award-winning jazz musician and Cirque du Soleil vocalist Malika Tirolien. She has also shared her verses with celebrated composer Andrée Greenwell for the choral project Listen to Me. Eunice co-produced and curated Harana, a series of poetry tours led by Filipina-Australians in response to the Passion and Procession exhibition in the Art Gallery of NSW. Her poems have appeared in Peril, Verity La, Voiceworks, and Deep Water Literary Review, amongst other publications. She was awarded the John Marsden & Hachette Australia Poetry Prize in 2014. In 2018, the Amundsen-Scott Station in the South Pole of Antarctica will feature her poetry in a special exhibition on climate change. Flood Damages (Giramondo, 2018) is her first book of poetry.

Eunice Andrada is a Filipina poet, journalist, lyricist and teaching artist based in Sydney. Featured in the Guardian, CNN International, ABC News and other media, she has performed her poetry in diverse international stages, from the Sydney Opera House and the deserts of Alice Springs to the United Nations Climate Negotiations in Paris. During a residency in Canada’s prestigious Banff Centre, she collaborated with award-winning jazz musician and Cirque du Soleil vocalist Malika Tirolien. She has also shared her verses with celebrated composer Andrée Greenwell for the choral project Listen to Me. Eunice co-produced and curated Harana, a series of poetry tours led by Filipina-Australians in response to the Passion and Procession exhibition in the Art Gallery of NSW. Her poems have appeared in Peril, Verity La, Voiceworks, and Deep Water Literary Review, amongst other publications. She was awarded the John Marsden & Hachette Australia Poetry Prize in 2014. In 2018, the Amundsen-Scott Station in the South Pole of Antarctica will feature her poetry in a special exhibition on climate change. Flood Damages (Giramondo, 2018) is her first book of poetry.

autopsy

Ma loads her gun with aratelis berries

shoots at Noy till the wildfruit explode

against his hair, then keeps shooting.

Syrup and rind spray against

their too-small shirts,

curl into the webs of their toes.

It is just after siesta and their backs

have been clapped with talcum powder.

The air is overripe

everything bruised and liable

to burst at the slightest touch.

Point of sale.

When dark begins to pour

around their laughter,

they abandon the wreaths of mosquitoes

that call them holy.

Splotches of juice blacken the soil,

punctuating the walk

to the dinner table.

In that festering summer, Ma learns

the futility of sweetness.

Ma is at work in another continent

when a dictator is buried in the Heroes Cemetery.

State-sanctioned killings begin

in her hometown. Twenty-six shots

to the head, chest, thighs

of two men.

I complain about the weather here,

how the cold leaves my knuckles parched.

Ma points to the fruit she bought over

the weekend, tells me I must eat.

February 28, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Elif Sezen, born in Melbourne in 1981, grew up both here and in Izmir, Western Turkey. She settled in Melbourne in 2007. Also an interdisciplinary visual artist, she writes original poetry in English and in Turkish. In 2014 she published her Turkish translation of Ilya Kaminsky’s acclaimed book Dancing in Odessa; her own first collection of experimental short stories in Turkish, Gece Düşüşü (‘Fall.Night.’), was published in 2012. Elif’s collection of poems Universal Mother was recently published by Gloria SMH Press, and she also published a chapbook The Dervish with Wings early 2017. She holds a PhD in Fine Arts from Monash University. www.elifsezen.com

Elif Sezen, born in Melbourne in 1981, grew up both here and in Izmir, Western Turkey. She settled in Melbourne in 2007. Also an interdisciplinary visual artist, she writes original poetry in English and in Turkish. In 2014 she published her Turkish translation of Ilya Kaminsky’s acclaimed book Dancing in Odessa; her own first collection of experimental short stories in Turkish, Gece Düşüşü (‘Fall.Night.’), was published in 2012. Elif’s collection of poems Universal Mother was recently published by Gloria SMH Press, and she also published a chapbook The Dervish with Wings early 2017. She holds a PhD in Fine Arts from Monash University. www.elifsezen.com

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

1 Awareness

Now that I am tired

I must open up inwardly like a lotus blossom

yes, I must open my paper-like lids

towards the benign feature of absence

for I will encounter her, in the very bottom:

that archetypal mystic, resembling my mother

by her glance perforating the silvered smoke

my small self will pass away

because I am tired

because fatigue is a lovely trap made to

save my body from its old cage

I learn to become still, yet

teleport simultaneously everywhere

I get rid of the worldly clock

losing beguiling sleep

I become a voluntary mute

so I can speak for them

They

surrender their souls

wrapped with flesh and blood and breath

back to where they came from

On the lands reigned by power issues

and tasteless hierarchy, they choose

the most desert-like spot

because a desert is a home for

repentance

The anima mundi is saved here

in discovering elements of

water, fire, air, earth and ether

through the heart’s eye,

once again

A lament is sung here,

one which only their forefathers can

hear. So each grief can be freed

like a crumbling piece of bread

for the animal-smile hanging

on the corner of the wall

is my primitive self whom I once

ignored

this is a new way of loving one’s self

For I am fatigued

and my fatigue will explode

like fireworks

upon you

2 Swans

Swans were drifting away on the lake

like forgotten desires, and we were

preparing ourselves for an

ordinary day

3 Metaphysics

Who said angels don’t exist?

O angels!

They are hidden in the elixir

of infinity that clears the conscience

of the unspoken

they light the soul-flame in its essence

they secretly orchestrate the flight of

glowworms, electrifying

and dying away towards the East

and towards the West

Whatever East and West means,

this is no secret:

direction does not exist the way we know it

direction is dimensional, not linear

This is no secret:

dying holds you back

not the way you know it

this time keep your angel by your side

and set off on your journey once again

4 The one without an answer

His papyraceous solitude

flows from the tower of innocence

to the lower planes of the cosmos

tickets tucked in the hands of

the one without an answer

5 The phenomenology of chronic pain

This Aria has no beginning, no end

whereas in the beginning there was the sound

the sound of Love dividing into bits

in between the matter and soul

Over time, the sound trans-mutated into

moans, arising from hidden wars

and declared wars

Yet today, right here, it

vibrates through the nerve-ends

of a young body

La Minor impatience

Do black humor

CRESCENDO the pain is so glorious here

First, talk to the pain

Dear pain, what do you want from me?

caress that pain, love it

surrender it to the whole

recycle it

and never forget,

suffering and not becoming monstrous

is a privilege

6 Hope

Close. Close your eyelids

to this landscape

forasmuch as this landscape

— preventing you from being you

once kept you alive

now it rather destroys

You were saying that this is

the memory of the future

you were rambling about a re-birth

in this future

for you were exceedingly dead

nothingness was tinkling after every death

O Rose-faced child,

the eagle

passing by the Pacific tangentially,

pure iron,

O well of meanings!

You must be empty while you hope,

for what already belongs to you is ready

to come back to you

“For to its possessor is all possession well concealed,

and of all treasure– pits one’s own is last excavated

— so causeth the spirit of gravity”

7 Flying

Forgiveness is what’s necessary to fly

also purification.

Even purifying from the desire of flying

yet a pair of wings is enough for most,

to fly.

8 Homecoming

Istanbul Airport is the doorway of my

time tunnel. No talking!

Act like nothing happened

hereby I discovered the reason

for the lack of bird-chirp

that others dismiss

because I am a bird too

I too forget the necessity

of flight

in all directions of the

forbidden atmosphere of mystery,

simultaneously

‘We must declare our indestructible

innocence’, grumbles my mum

her eyes staring towards the

beyond-horizons

The birds pollute the new President’s sky.

A deaf child disappears from sight

in the alley, after listening to the song

which only he can hear

I call him from behind, with no luck

and find myself in

Melbourne again, inevitably

I chop and add mangos into

my meals again

I forget the malevolence of a

suppressed father image again

I forget my most favorite scent,

jasmine

how holy this forgetting is, I know

for it will pull me back to that doorway

for I’ll want to go back home again,

home without geography

without footsteps

how sweet is my abyss.

No memory of fatigue.

I’ll again make merry.

9 One more century

In every cross-section of the secondary mornings

there lies a magic

the winking sun, resembling archaic

portraits of women

make each body solve one more mystery

so that one more century passes.

REFERENCES

The final three lines of the section ‘Hope’ are from Friedrich Nietzsche. Thus Spake Zarathustra, trans. Thomas Common, Wordsworth Editions, 1997, p.188

January 24, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Heather Taylor Johnson’s recent publications are Meanwhile, the Oak (poetry, Five Islands Press) and Jean Harley was Here (novel, UQP). Heather is the poetry editor for Transnational Literature and is edited Shaping The Fractured Self: Poetry of Chronic Illness and Pain.

Heather Taylor Johnson’s recent publications are Meanwhile, the Oak (poetry, Five Islands Press) and Jean Harley was Here (novel, UQP). Heather is the poetry editor for Transnational Literature and is edited Shaping The Fractured Self: Poetry of Chronic Illness and Pain.

In-between

1.

How do I talk about home? How do I communicate the distance between Adelaide and Sydney? It’s easy to calculate kilometres and round off to the half-hour how long it might take to drive the distance, but how do I measure the pull from one place to the other? I believe there was a beginning and there is a now (there can never be an end) and it’s the in-between we rip apart, trying to get at the bones of big things, like love and loss and home. How many minor poems begin and end like this:

Adelaide, I’ve seen the square of your heart pulsing in the heat,

your brown-veined river tapped-out and rank, your black fingers

touching the sea and pricked on the lovely vine – I have tasted

your blood and it tastes like wine. Once I considered getting lost

(an impossible fate) then decided to go home but the train

was late. I hear drums in the park and follow their beat,

discover giant fig trees at my feet. When I say your name Adelaide

my tongue is a snake sliding over your hills, all scales, no feet.

I pick late-night falafel from my teeth.

I’m in Sydney, on my way to the Blue Mountains, a writers’ residency, a yellow house. It once belonged to the writer Eleanor Dark and her husband, Eric, and they called it ‘Varuna’. There are stories of Eleanor’s ghost, how you can feel her beside you when walking down the stairs, how noisy she is when she climbs the ladder (it would seem she is always moving, a restless ghost). I’m going to Varuna to write about illness and art and live with ghosts for ten days: Eleanor’s, Vincent Van Gogh’s, the ghost of my healthy body. I have a beginning and I have a now, and in-between the beginning and now illness birthed a ghost that breathes in experience and exhales memory and I need to write the stories. I’m going to inhabit that ghost, make sense of its loves and losses, make sense of its homes.

*

There are five of us and a dog in Adelaide. I cannot write about myself without writing about ‘us’. To write about illness is to write about the body – the whole body – and they are each a part of mine. The boys are my limbs; without them I couldn’t jump or high-five. The girl is my core, giving me she-woman strength. When you roar, it comes from the core. Also when you sob. Also when you laugh. My husband is my heart and it’s his blood that fuels me. His blood which is mixed with the blood of so many others from the time he died, twice, then came back to life. He thinks he survived so that we could meet and my body make our babies. And let us not forget the dog. The dog is my bowel; I need him daily in a very basic and simple way. Like I need shitting, and I don’t mean it to sound cruel or crass – I always mean to sound like a poet. Without my family, my body breaks down, and I know from experience that the essential ‘I’ of me will follow. This then means: without my family, I cannot write.

And yet, and yet, it is near-impossible to write with them around me, touching me, demanding of me, taking from me. And yet, and yet, I find I want to write about them constantly when I’m away.

To write about my body, I must write about ‘us’. I must write about home.

Here is a short definition of home:

My agent, Jo, brought me to her home for the night, where her child slept in her bed and I slept in his. His stories hung on his walls and littered his floor; one was paused in the middle of the telling, lying patiently on his desk. Their dog snuffled about then left me to sleep, toddled into their room.

How nice it is to feel welcomed, to hear a person say, This is my home, all of this is me, and you are welcome. I think Jo likes my writing because I write about family.

In the morning she drove me to the ferry at Manly. ‘It’s much nicer than going through the traffic,’ she said, and what I didn’t say was ‘Travel by water makes me sick.’ But then so does traffic. Coming to the Blue Mountains will not only be good for my writing but for my illness, too. There are many complexities in trying to determine why this is but I think it has a lot to do with not driving. My peripheral vision is in overload whenever and wherever I drive and it tires me out. School pick-ups and drop-offs, the neverendingness of groceries, the children’s sports, their music – I’m looking forward to the speed of walking over the next two weeks, the heaviness of ghosts in the yellow house.

2.

I’m sitting on the lower deck because any higher my stomach might fall overboard, scaring fish and scattering cigarette butts. What is it with smokers who don’t think their butts in the sea are as bad as an empty bottle? There is a man smoking on the upper deck and I wonder if it’s allowed. Where, these days, is smoking allowed? (Vincent with his pipe is my favourite self-portrait.)

Everyone has their phones out so they can take photos of the Opera House and the Harbour Bridge, but when we come to the blue gap between the land that is Manly and the land that is known as The Rocks – the place in the centre, where water expands unfathomably, where there is a certainty of far-away – I take a photo. It is nothing but an empty horizon. I call it longing.

How many waves between the country where I live and the country where I was born? How many breaths? Australia and America: both are my countries yet neither are, home being a multi-layered thing and liminal at the same time; inaccessible by travel alone; too many steps, or laps, or blind grasps. That water, between the gaps of raised rock and the thin outer soil, forms a line, a plane, a motionless expanse that I know to be false because life is moving, always. Life is shifting and sinking and flowing, as in the shallow water of this harbour and the deep water beyond, as in Van Gogh’s peasant fields and the paintings of them that won’t sit still, in the rumble of dirt beneath Adelaide’s streets, and in the sands that gather and pile and amalgamate with tiny bodyless spiders’ legs in the cracks of Adelaide’s sidewalks, where debris makes homes for Adelaide’s ants. What intricate scapes tunnel below our feet.

*

I grew up in a mobile family, my father accepting promotions and my mother organising moving vans. She was a nurse and my brother and I children, so the three of us slotted right into wherever we had to live (there is always need for a nurse; suburbs crave children). By the time I was twenty-two I had lived in eight different cities in seven different states, on both sides of the Mississippi, north and south of the Mason Dixon line, too. No landmark or smell connected me to home. What is home when the silverware drawer and the cupboard for cups elude me? Naturally I filled out an application to become an international student after I’d lost my first love and of course I was gone two months later: over-the-ocean, across-the-dateline, of-a-different-hemisphere gone. Home had always been a moveable feast and I was twenty-five, hungrier than ever. That was almost two decades ago. Since then: almost twenty years of the same city, the same local beach, the same land. Almost long enough to call Australia home.

Van Gogh shifted homes when he needed to run towards, traversing the Netherlands and Belgium for a connection to the people and the land and his family and God, London for work, Paris and Arels and Auvers for art. What was home to him but a string of failures that we see as steps to his martyrdom? How conspicuous he must’ve felt with his thick Dutch accent and strange surname. He hated how the French pronounced it ‘Van Gog’ so signed his paintings with ‘Vincent’ to avoid further frustration.

To talk about home we need to talk about language and accents, culture and history, family and, yes, the body. I’ll call Australia my eyes and America my mouth. Perhaps home is the space between the two and to the left: my ear, faulty and to blame for my disease. Is it coincidence I became sick with an imbalance disorder when I moved from one country to the next?

I come from six lane highways and bridges over creeks,

the kudzu vine, the ubiquitous pine, from toll roads

and squashed toads. I come from the North Star, Stone

Mountain, the crash of Big Sur’s waves. I am cactus poison

and acid rain; obesity and the tobacco leaf. I’m from humidity

and plastic Santas loud atop the silent snow, from lightning

bugs and those camp songs my children laugh at when I sing,

songs I sing to make them laugh.

3.

When we dock in that iconic part of Sydney, when I step off the ferry and step onto land, I am nauseous, the waves too much for my travelling ambition. I am glad for the hour reprieve before I catch a train to the mountains. I am glad for my notebook, pen, these thoughts, this writing, though when I look up from all of this gratitude, I am even more unsteady. In need of a nap to set me straight. A Coca-Cola will do. Always does. Embarrassing to wear your country of birth not around your neck or on your sleeve but stuck to your mouth which sucks in the bubbles that settle your stomach because you suffer from nausea. Though I believe sometimes you have to give yourself a break. One needn’t be political about small vices when there are so many other things wrong in the world.

Right now, in America, there is Donald Trump raised higher than Trump Tower and having no fear of any aeroplane crashing into him and taking him down, no fear of a missile aimed at his gut. Does he comprehend an American implosion, an inside job where citizens fire away with all of those automatic guns? I’m rubbing my face now. Whenever I think about Trump or America’s gun problem, I obsessively rub my face.

I’m supposed to return home to see my parents and brother and his family soon. I won’t go home. But I will return to America.

It is possible, I suppose, to miss home terribly, not know what home really is anymore, and refuse to go home, all at once:

James Woods has described this other chronic condition as ‘homelooseness’[1], going on to say, ‘Such a tangle of feelings might then be a definition of luxurious freedom’. Because I’m not a forced exile. Because I’m not a refugee. I left the only home I’d ever known to make a new one. Because I wanted to. Because I could. And yes, I miss the rivers and lakes, miss the mountains of America, miss the roads that lead to anywhere and everywhere, miss my parents and brother, so yes I miss America. I’m tethered and the strings are taut. But is it home to me when I cannot fathom how a nation could support a man such as Donald Trump? Is it home now that my vowels, the lilt of my words and the jargon I use sound foreign even to my own ear let alone to those who ask me where I’m from? Can it be home if I no longer live there, know bus routes, have a favourite restaurant, favourite radio station? In the spirit of homelooseness, I will return to America only by refusing to return ‘home’. The two names have become such luxurious contradictions that it’s impossible to consider them one and the same.

Van Gogh went back to his family in the Netherlands again and again when he was sick, but it never worked. Feelings of failure. Angry words. His paintings of that homeland are dull in colour, so different from the yellows and teals of Arles, his haven-home, the one he chose, where he lived in his own yellow house and the people all thought him a madman. (How to communicate the lonely distance between his two homes? How to define his terms of condition and stamp it on a landscape?)

I can and will go back to America again and again because I know Adelaide, my own haven-home, will always be waiting for my return. It is why I will come to terms with the American population for voting in Trump, who is making the skin fall off of my face. It is why I can do this now: leave my husband and my children and my dog back home so that I can write about illness. So that I can write about them.

Just. Need. To get. To. The yellow. House.

And all around me at Central Station people are moving. I swear I can see the energy of the molecules between their busy bodies. It’s almost pixelated. A dance. Wrappers are moving on the concourse from the wind on the platform. Even the idling engines inside the trains are moving, their pollution sifting upward and mixing with that same wind. Everything is connected. The wind is my head. (It is always my head.) The fluid in my ear is moving in time with the lift and fall of bile in its intricate tunnel of intestines and sacs. What if the ferry ride has lasting effects and I’m sick for days or weeks? I’m on my way to the Blue Mountains without my family – who make up my body – to write about the body and illness, and I might be too sick to write. Who will I complain to? Who will I squeeze security from? I might find ‘home’ a difficult word to define but I know it’s partly a place where you are comfortable being sick. Anywhere else can be called ‘unfortunate’.

4.

I’m anxious about the impending train ride, when the world will screech past my window – a stone wall blurred, stampeding trees. Even the sun will slam down its rays like a procession of gates trying to capture the forward-moving time. The tyres on the thing will roll as if trying to tame New South Wales, though it – the land – is unruly, uncompromising, will have its way through swells and swerves, through juggling ruptures. I know this already because I love to travel, just hate the travelling.

A long day, a wild journey for someone with the luxury of freedom, but it will be small in comparison to flying across the world to get back home. (See how I use the term fluidly? As if I was an underwater lava bridge connecting two lands.) My acupuncturist thinks a body isn’t meant to move from one magnetic pole to the other in a matter of hours and that a malfunctioning body will rebel. Why whenever I go to America she sticks on strips of tape holding tiny needles that quietly treat me for days. Why I see her within the first few days of my return to Adelaide for maintenance because travelling will always shake up my illness

But she thinks this is a good idea. Not the travelling but the travel, the space and the time on my own. A holiday away from home.

*

The house on Herbert Street, call it a rectangle. It’s got rooms on either side of the hallway. Most are bedrooms but one is the living room (the couch room, the fire room, the television room, the room of constant gathering), and that is the second most important room in the rectangle, the first being the kitchen. I could’ve said the most important room was the bathroom or the toilet but I’ll remind you: I am always trying to be a poet. And after all, the kitchen’s where the hallway leads, which is like the dot at the end of the exclamation point. A directive. A designation. A destination. The room revolves around food and, more than anything, bodies need food. So we are mostly there chopping and slicing in our bodies, perusing pantries and refrigerators in our bodies; eating, singing, hugging, screaming, dancing and talking in our bodies in the kitchen; the room is rarely bare of us. Outside is a backyard full of one-day-I’m-gonnas and scattered stinging nettle seeds. There’s a trampoline and a wooden cubby house with a rustic ladder that’s unattached to any tree, but because it sits among climbing vines we’ve always called it a treehouse. Green is good for the imagination just as it’s good for the lungs. And that’s really what I think about our backyard: it’s a place to breathe.

I board the train bound for Katoomba and sit near the front on the bottom level, where the least amount of perpetual motion occurs. I’ve been on this train before and sat on the upper level, threw up into my water bottle until it was full then asked someone close to me for their empty coffee cup. Two and a bit more hours of travel and I’ll put down my bags in my room at Varuna. I’ll lie on the bed and rest before the welcoming drinks, where I’ll try to appear happy-to-be-here when really I’ll be just-plain-tired. At night, I’ll lie down in bed, thinking about Van Gogh’s yellow house, how he wanted it to be an atelier for a host of painters in southern France and when it didn’t work out, he was devastated, hacked at his ear, got so sick he never really recovered. I’ll fall asleep, dizzy but exhausted, and if the ghost of Eleanor Dark wakes me, I’ll tell her thank you for welcoming me into her yellow house. Such a lovely home.

*

When the train starts to roll I’m looking out the window. Sydney spreading then thinning then suddenly gone. Then pockets of other ways of living: outer suburbs and mountain towns. In America, I trialled them all. I made a home in a desert city where front lawns traded boulders for grass and one in a suburb of contemporary houses, all angled and wooden and upper-middle class. One had a front porch overlooking a proud town preserving its Civil War façade. Women in bonnets swept the sidewalks on Saturdays. All of these, stepping stones to the rectangle which I call home, though naming it as such suggests that home is an object, when what I really want to say is that home is everything within and surrounding the rectangle, everything fragile about my upbringing, everything sacred about my connection or disconnection to America and to Australia. More than the beginning and the now, it’s the in-between.

[1] Woods, James. ‘On Not Going Home’. London Review of Books, vol. 36, no. 4, 20 February 2014, pp. 3-8, http://www.lrb.co.uk/v36/n04/james-wood/on-not-going-home

January 23, 2018 / mascara / 0 Comments

Can You Tolerate This

Can You Tolerate This

by Ashleigh Young

Giramondo

ISBN : 9781925336443

Reviewed by MARTIN EDMOND

Can You Tolerate This? is a collection of twenty-one personal essays on a variety of seemingly disparate subjects; some just a few hundred words long; others more than thirty pages. All are highly accomplished, both stylistically and in terms of the use they make of their author’s existential, experiential and other concerns. They are also, in way that is subtle to the point of subversion, very amusing; but it is a painful kind of humour, reminiscent of the paroxysm of pain we may feel when we bang our elbow on some hard surface like a wall or a door or the arm of a chair, and activate our funny-bone.

Bones are in fact where the collection begins, with a short account of the life of an American boy who suffered from a rare disease which caused another skeleton slowly to grow around his original one. This introduces a major theme of the collection, its examination of the complexity of the mind-body relationship, using a variety of curious examples from the world but mainly employing the author herself, her defaults and her daily activities, the various milieu in which she moves, as a subject for speculation—often of a rather fraught kind; but therein, as I said, lies the humour.

So this is the first point to make: although the book may seem to be a collection of disparate pieces, it is in fact a highly wrought artefact, as unified as any good novel or memoir may be; in fact, better unified than most. One of these unifying factors is the body / soul dynamic, mentioned above, wherein the author inquires into her own condition, or habits, in such as a way as to try, not so much to explain them, as to escape from some of their more oppressive effects. Here, through a curious alchemy, the compassion which she shows to others, like her dying chiropractor (in the title piece) is somehow, perhaps by means of the excellence of her style, extended to herself—and by analogy to her readers, who will recognise in the author’s predicaments the ghosts of their own.

This kind of ‘therapeutic’ writing can, in less assured hands, come across as awkward, self-serving or even self-pitying; but not in this case. Ashleigh Young’s voice is bracing and illuminating; although she is often tentative, sometimes almost to the point of hyper-sensitivity, she is always honest; and these are the qualities—honesty, illumination, vigour, sensitivity—that make the collection so beguiling. Whether she is practicing yoga, going for a bike ride, adjusting her breathing to the demands of cycling or running, as a reader you experience a feeling of rare empathy with the authorial voice.

So her self-portrait, or rather her succession of self-portraits, is entirely successful. In part this is because of another, and deeper, unifying aspect to the collection: deftly, without ever really seeming to try, almost by stealth, Can You Tolerate This? is also a portrait of the author’s family and, as a consequence, an account of her growing up in the small town of Te Kuiti in New Zealand’s North Island, with some holiday sojourns at Oamaru in the South. As the book proceeds, especially through its longer essays, we come to know her family—her father and mother, her two older brothers, herself, various family pets—almost as well as we may know our own. This splendid family portrait is achieved without recourse to whimsy, cuteness, or special pleading; most of what we see is far too raw, and too real, for that. In some respects this is the most remarkable aspect of a very remarkable book.

The long essay, ‘Big Red’, for example, is almost unbearably tense to read because of the sense of risk expressed in its account of the erratic career of Ashleigh’s much-loved older brother JP (who calls her ‘Eyelash’); that something untoward might happen to him, though in fact nothing does, gives the essay the character of a thriller. Moreover, and this is an example of how highly wrought this collection is, that feeling of incipient dread does pay off, much later in the book, in the catastrophe which afflicts the other, the elder brother, Neil, by now living in London. I won’t, of course, say what that is.

The father, with his benign eccentricities, his obsession with flight, his odd remarks; the mother, too, in her attempts, for example, to banish from mirrors the reflections of all those who have ever looked into them, become as vivid as the two brothers. The account of the mother’s writing life, which, in the piece called ‘Lark’, concludes the collection, accomplishes something almost unprecedented: a merging of voices, in which we become unsure if we are reading the mother’s writing or the daughter’s redaction of it. This is, apart from being a stylistic tour de force, an example of familial love raised to a higher power—and brings the book to a winning, if poignant, close.

Like its thematics, the book’s writing proceeds by indirection. Young’s prose style seems relatively straightforward, unornamented or only lightly ornamented; yet her sinuous, seductive sentences take us, almost inadvertently, into very strange places indeed. Witness, for example, her digression upon women’s body hair (‘Wolf Man’, p. 138) which begins: My moustache was negligible in comparison to the hair on the faces of these women and ends The discomfort grows from within, as if it had its own dermis, epidermis, follicles. This is because she is, as a writer, incapable of dishonesty—neither the larger sort which invents in order to cover up, or divert attention from, uncomfortable things; nor the smaller kind which prefers something well said to something, perhaps painfully, or hilariously, true.

This is a brave, sometimes confronting, always intriguing, often compelling, and distinctly unusual book. The essays are consistently entertaining in a way that is rare in literary non-fiction of any kind. The voice is one which readers will fall in love with; they will actively wish for the author to succeed in her life’s endeavours; while recognising that success may be an impossible goal; or, at the very least, a goal impossible to measure. They will feel the same way about the wonderfully eccentric, though entirely typical, Young family, right down to the miniature dachshund with the back problem.

A warning for Australian readers: Ashleigh Young is a New Zealander and her book, republished by Giramondo in the Southern Latitudes series, with a stunning cover by Jon Campbell, originally came out in 2016 from Victoria University Press in Wellington. Ashleigh Young won, along with Yankunytjatjara / Kokatha poet Ali Cobby Eckermann, also a Giramondo author, one of eight coveted Yale University’s Windham-Campbell Prizes, worth $US165,000, awarded in 2017. But that may not be enough to banish the instinctive, almost visceral, disregard most Australian readers have for works from across the Tasman; as if nothing that comes from there could ever rival the terror and the grandeur the best Australian writers are able to command. Nor the inadvertence and obtuseness of the worst.

I don’t quite know what to say about this ingrained prejudice. As a New Zealander myself, albeit one who has lived nearly forty years in Australia, I have never yet been able to compose (it is not for the want of trying) the aphorism that would encapsulate, and so detonate, this unwillingness to engage with a close neighbour. I think that the domestic economy in Aotearoa may be so fundamentally different from the one here that Australians cannot go there. I mean it is so tender and so violent, so intimate and so alienated, so intricately genealogical, that to do so would risk a vastation.

Ultimately, perhaps the problem is the accommodation, however imperfect, between indigenes and settlers that Aotearoans have embarked upon, which remains as yet unattempted here. This of course opens up another interpretation of Ashleigh Young’s title; as if it might be addressed to all the nay-sayers among us who might instinctively resile from a book that comes from so far away, and yet so near at hand, as Te Kuiti. But it also augments the original meaning: some kind of fundamental readjustment of skeletal, no less than existential, or even spiritual, structures might result. It might even be the intention. Can you tolerate this? You could try.

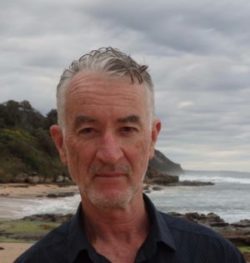

MARTIN EDMOND was born in Ohakune, New Zealand and has lived in Sydney since 1981. He is the author of a number of works of non-fiction including, Dark Night : Walking with McCahon (2011). His dual biography Battarbee & Namatjira was published in October 2014.

December 19, 2017 / mascara / 0 Comments

Michael Adams is a writer and academic living near Wollongong. His work has been published in Meanjin, The Guardian, and Australian Book Review, as well as numerous academic journals and book chapters. His essay on freediving, loss and mortality, ‘Salt Blood’ won the 2017 Calibre Essay Prize.

Flood

He has driven down in tears in the car from the conversations with the psychologist, and the way they run the retreat lays bare his emotions even more (a woman he doesn’t know next to him on the mats is also sobbing). By Sunday first thing he is a mess, and after the early morning meditation session feels shaky and vulnerable. He cannot bear to be with other people, so walks across fields to the river. It has been raining for days, everything is sodden, green, muddy.

But the river is a vision: huge, swollen, patterned, powerfully moving, the great sweep of current surging down. It has swelled over the banks, completely fills the low valley. The sky is unbroken white, rain is hammering down, a percussion of sound – water on leaves, on wood, on mud, on water. The river itself makes no sound, the enormous powerful surge of current totally silent. It is a great block of muted colour with a mobile, patterned, articulated surface.

A bird flies heavily away from low branches, dark in the clouded morning. There is no one here. He strips on the flooded ledge, piles his clothes in the wet fork of a tree, steps naked into the water. The air is warm and humid, the rain cold on his shoulders, his feet grip the sliding mud. He takes another step and dives, swims hard into the middle of the river, strokes strong and precise. The river is cold but he feels encased in his warm body, the cold just flowing over his skin, not reaching his core. When he pauses to orient, the far bank looks like the Amazon, a dense wall of wet green forest coming down to the water’s edge.

In the middle of the swollen current he feels good, his body reliable. The joy and wild beauty of the swim have recalibrated him. The current is pushing fast and he turns upstream to gain some distance. Eyes open, the light glows through brown silty water, eyes closed he is back inside his warm body. Swimming hard and gracefully, there is a sudden massive shock – a split second of realisation, the broken tree trunk swirls past, blood in his eyes, blood in the brown water. He feels his slackening body roll in the dark flood.

December 19, 2017 / mascara / 0 Comments

Cameron Morse taught and studied in China. Diagnosed with Glioblastoma in 2014, he is currently a third-year MFA candidate at the University of Missouri—Kansas City and lives with his wife Lili and newborn son Theodore in Blue Springs, Missouri. His poems have been or will be published in New Letters, Bridge Eight, South Dakota Review, I-70 Review and TYPO. His first collection, Fall Risk, is forthcoming in 2018 from Glass Lyre Press.

Cameron Morse taught and studied in China. Diagnosed with Glioblastoma in 2014, he is currently a third-year MFA candidate at the University of Missouri—Kansas City and lives with his wife Lili and newborn son Theodore in Blue Springs, Missouri. His poems have been or will be published in New Letters, Bridge Eight, South Dakota Review, I-70 Review and TYPO. His first collection, Fall Risk, is forthcoming in 2018 from Glass Lyre Press.

Centerpoint

Crossing into the main hospital, I remember

the bruise of my past life, thunderheads

of scar tissue in the crook of my arm, vials

of blood drawn weekly while I ate Temodar.

I remember the red river of platelets, lymphocytes,

and white blood cells that sprang

from my weariest vein. After two years,

I’m returning to Centerpoint Medical Center

as another man, a man accompanying his wife

on the hospital tour that will give them triage,

labor rooms, and the mother-baby unit

where she will rest after giving birth to their firstborn

in October—a man with no bracelet around his wrist,

no name, no date of birth, no questions asked.

Apnea

noun, Pathology.

1.

a temporary suspension

of breathing, occurring in some newborns

in the early morning

dark where I walk. When it sounds

as if the whole world is holding its breath, waiting

for a squirrel to pick itself up

and walk away from its body and brains

dashed along the curb, prostrate,

I-70 murmuring like a lamasery

beyond the rooftops, a road tossing

in its rocky bed, all the contrivances of man.

Beside the squirrel, oak leaves choke

the storm drain. No one is coming

to clean up the mess.

December 19, 2017 / mascara / 0 Comments

Rebecca Vedavathy is a research scholar studying Francophone Literature in EFLU, Hyderabad. She began writing as a child but only discovered its appreciation when she read a Francophone Literature class many years later. She won the Prakriti Poetry Contest, 2016. She longlisted in English Poetry for the Toto Funds the Arts Awards, 2017 and 2018. She is currently a Shastri Indo-Canadian Research Fellow interning at the University of Quebec, Montreal.

Rebecca Vedavathy is a research scholar studying Francophone Literature in EFLU, Hyderabad. She began writing as a child but only discovered its appreciation when she read a Francophone Literature class many years later. She won the Prakriti Poetry Contest, 2016. She longlisted in English Poetry for the Toto Funds the Arts Awards, 2017 and 2018. She is currently a Shastri Indo-Canadian Research Fellow interning at the University of Quebec, Montreal.

Autumn blood

Some days I stand in my choicest place:

a poem

with a leaf

I stand

and let the tree eat me.

Words hang like apples sewn to a tree –

the head of a poet – what was his name?

Didn’t the goddess tell you, it’s not safe to let

thoughts form words on your lips?

They aren’t red like hers – betel leaves don’t work.

Words draw shorelines on a passport –

the Syrian baby flattened on a sandy beach.

Didn’t the griot tell you, children here

don’t build sandcastles, anymore?

Lessons on geography and gore.

Words lay battered, dead against graffiti walls –

Dalit child and Muslim man.

Didn’t the bishop tell you, baby cows are

called Mein calves now?

No, cow urine isn’t red – enough said.

Words explode on the lazy newspaper –

shrapnel and body on boulevard – Paris.

Didn’t the ambassadors tell you, you’ll

pay for open borders?

They probably forgot – Gotham city in rot.

This poem has broken ribs and a lost ear.

Where shall I find it?

Beirut or Paris?

I don’t want to stand here anymore.

The autumn leaves are mulched with blood.

Veins slit, roots flung. Run.

Left I scream.

The nation hears, pretends these are bad

words hiding in a pencil box –

learnt to be forgotten.

This poem has breath. It shall remember.

It shall eat the mud, the blood

democracy feeds us

and rise

into red autumn’s green sister.

how to preserve childhood

red monkey insides

part-time job: museum

fulltime job: friend

friend because monkey was not alive. he was a he though. i didn’t name him. he was red. velvet. not like cupcakes. i am sure he didn’t taste like cupcakes. that’s because i tasted him. he tasted like fine red threads. touching tongue. tickling. he was as dirty as my feet. my feet went places those days. without chappals. climbed mountains of construction sand. dragged monkey’s curly tail. a cursive ‘g’ with me. fed him sand. ate some. licked deworming syrup from measuring cups. bit around his black button eyes. an attempt to make them look like mine. he still didn’t look like me. no one with three stitches for a nose looks like a little girl. that was the thing. he was a boy. i burrowed my fingers in his torn armpit. he didn’t mind. like i said he was my friend. i told him my secret. pineapples are just big apples, i declared. that’s why they have longer spellings. right? he heard me.

one day before convent school taught me “it is raining”. “rain was coming”. and when it came it came down with hail stones. no one was watching. i picked them up. one by one. silver sharp edges. taste of melting. white glass. tongue curled in cold. upside down camel hump. we didn’t have a fridge. i marched to monkey. stuffed his armpit. he had an armpit full of hail stones. i forgot about. later when i looked for the hail stones. monkey was a soggy mess: a museum.

a year later, we bought a fridge. it came with a fridge box. bubble wrap. a cover. that year i played a fridge for fancy dress. the box was my body. i had lines and all. i licked ice from the freezer. it tasted like fridge. i never saw hail stones again.

monkey appreciated that.

December 18, 2017 / mascara / 0 Comments

Rose Lucas is a Melbourne poet. Her first collection, Even in the Dark (University of WA Publishing), won the Mary Gilmore Award in 2014; her second collection was Unexpected Clearing (UWAP, 2016). She is currently working on her next collection At the Point of Seeing. She is a Senior Lecturer in the Graduate Research Centre at Victoria University.

Rose Lucas is a Melbourne poet. Her first collection, Even in the Dark (University of WA Publishing), won the Mary Gilmore Award in 2014; her second collection was Unexpected Clearing (UWAP, 2016). She is currently working on her next collection At the Point of Seeing. She is a Senior Lecturer in the Graduate Research Centre at Victoria University.

Family Portrait

Van Dyck, c. 1619

In their best Flemish clothes –

lace ruffs and jewelry, brocaded fabric –

this young couple gaze

intense and hopeful

out of the canvas;

they lean toward me as though

all this

were as fast as the shuttering

of a lens;

their bonneted child,

dandled on her mother’s knee,

looks behind and up –

she has no need to look my way;

Her parents are vibrant with

youth and prosperity,

their connection to each other,

their pride in the child;

like every family –

holy in their ordinariness –

they hold the unfolding generations

squirming

in their richly upholstered arms:

Look! we have made this future –

it belongs to us.

Only consider –

(and here the benefit of hindsight)

their willingness to pause,

to sit while a painter

composes

studies

takes their likenesses

in pigment and brushstroke,

placing them

lovingly

within the rushes of time –

Look carefully –

hold fast to the slipperiness of this moment –

it will not always

be like this.

From Mallaig

Heaving out from the harbour,

its narrow lean of wooden houses,

salt-weathered in a cloudy light –

a ferry clanks and judders

picking its way past little boats,

their tangle of nets

and out into the slap and wash of darkening water:

stink of diesel and fish swim

in freshets of air,

rubbing cheeks into ruddiness;

until the hump of island

sails into view –

its possibilities of destination,

palette of smudged greys and greens

flickering through the glass;

the angular spine of the Cuillins

scrapes against

a loamy sky,

writhing in channels of wind;

while, deep in boggy fields,

something

shifts,

restless in peat –

These tannin-soaked fields,

this permeable membrane,

this elongated moment when a boat might

clip and ride,

a shoreline in sight.

December 17, 2017 / mascara / 0 Comments

Rafeif Ismail’s current work aims to explore the themes of home, belonging and Australian identity in the 21st century. A third culture youth of the Sudanese diaspora, her goal is to create works that blend the traditional elements of the arts of her home country with elements of classic and contemporary western arts. She is committed to writing diverse characters and stories in all mediums, is currently working on her first novel and hopes to also one day write for screen. She can be found exploring twitter @rafeifismail

Rafeif Ismail’s current work aims to explore the themes of home, belonging and Australian identity in the 21st century. A third culture youth of the Sudanese diaspora, her goal is to create works that blend the traditional elements of the arts of her home country with elements of classic and contemporary western arts. She is committed to writing diverse characters and stories in all mediums, is currently working on her first novel and hopes to also one day write for screen. She can be found exploring twitter @rafeifismail

Almitra Amongst Ghosts

Houah Maktoub, your grandmother always used to say, it is written. She firmly believed that everything that will ever happen had already happened, that distance and time were no obstacle. You used to sit by her side, in the shade of a veranda overlooking a courtyard, in that house surrounded by tall walls painted white, with its metal gate that was green with age, always open. You listened, your fingers sliding across the imperceptible thorns of the okra you handed her which she expertly cut for that night’s dinner as she told stories she had grown up learning, in the village on the island between two Niles. Stories of family, friends and legends, she had weaved them together like a dark Sahrazad. It is where you first heard of Mohamad, the village boy who lived on the edge of the savanna, who cried, tiger! tiger! tiger in the grassland! Until no one believed him, and his whole village was massacred as a result. And of Fatima, who sang so sweetly that a ghoul stopped the Nile for her, so that she may retrieve her lost gold. Of the spirits in the rivers, those on land and ancestors who whisper in dreams, reaching out from some other world with warning and advice; years later, you will learn that quantum entanglement posits that two more objects may exist in reference to each other regardless of space time, and think on how much physics sounds like her folklore and faith. At your grandmother’s side you learned of a world three parts unseen and believed in it. Now those days seem hazy and distant, and there is a space in you, that twinges like phantom limb, as though you lost something you did not know you had, somewhere along the invisible borders between what you thought was home and here.

***