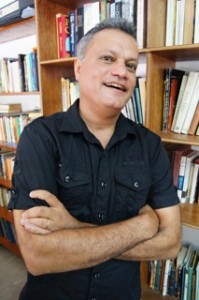

Sudesh Mishra was born in Suva and educated in Fiji and Australia. He has been, on different occasions, the recipient of an ARC Postdoctoral Fellowship, the Harri Jones Memorial Prize for Poetry and an Asialink Residency. He is the author of four books of poems, including Tandava (Meanjin Press) and Diaspora and the Difficult Art of Dying (Otago UP), two critical monographs, Preparing Faces: Modernism and Indian Poetry in English (Flinders University and USP) and Diaspora Criticism (Edinburgh UP), two plays Ferringhi and The International Dateline (Institute of Pacific Studies, Suva), and several short stories. Sudesh has also co-edited Trapped, an anthology of writing from Fiji. His creative work has appeared in a wide array of publications, including Nuanua: Pacific Writing in English since 1980, The Indigo Book of Modern Australian Sonnets, Lines Review: Twelve Modern Young Indian Poets, Over There: Poems from Singapore and Australia, Sixty Indian Poets, The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poetry, The HarperCollins Book of English Poetry, The World Record and Concert of Voices: An Anthology of World Writing in English. Sudesh is working on a fifth collection of poems, a collaborative project on popular Hindi cinema (with Vijay Mishra) and a series of papers on minor history. He is currently Professor in Literature, Language and Linguistics at the University of the South Pacific.

Photograph by Semi Francis

Envoi

Every day straggler word-bees fly up

His nostrils to swarm in the cold bone-urn

Of his skull; and all winter they settle

On the atomic flower of his brain

Which radiates no light the hue of nectar,

Dry and dyeless as a reef in a book.

So drinking of desolation they die

With a shudder of wings on the bone-floor,

And although their ashen remains swirl up

In a wind that is no wind of nature

To serve him an apparition of spring,

He’s sly to the artifice in its art

And waits for a sudden trick of season

That lures with light the vocal survivor

To tropics that ignite beyond his skull.

And sighting a reef of nameless flowers

It lands a name on all that namelessness,

Sipping at alphabets, making honey.

Fall

Amid the swish and buffeting

Of archangels’ wings, the city

Of angels left behind, howling

At the pact between god and man,

I lost faith with the force of faith

And cried to be a child again,

Striking out at the stars striking out,

A fever driving my fevered chalk

Through points of skyfall light,

Up and right and left and down,

Reverse, transverse—all night.

Until there you were, my Father,

A most furious constellation

By the bitter furies composed.

Ambulance Driver

The phone leaps to unbead

The rosary of sleep

Before you pick it up

On the other side of

Dreaming. We sink deeper

Into cool valleys

Of pillows, snuffing out

The crunch of dry gears

And convulsing light

That gives notice of

Your night errant to streets

Of hurting and dying,

Of unsleeping houses

Where Pain makes faces

Like a spoilt child.

You’re Delivery Man,

Shuttling flesh from house

To hospital to house,

But taking no man’s wage,

Though rouged Capital

Tries chatting you up

At every traffic light.

No, never commodity,

Your compassion runs

Like a seam no miner

Dare harvest nor priest

Baptise as Religion.

And when prodigal you

Return to cool valleys

Now overrun by trolls

And ogres, like us they

Too suffer an alchemy,

Turning into songbirds

On boughs of groaning fruit,

And all the terrors burn

Like music in our ears,

As mangoes in our grip.

Seal

When you surfaced,

Berry-eyed, boxer-nosed,

Cub of the ocean,

We were ruminants

Startled out of ourselves,

The deliberate, alluring hunger,

The browsing on interior lives.

My rubbery periscope,

My submarine voyeur,

How you nod from left to right,

From right to left,

Now as you did then,

Wet brat of inspiration

Affecting dolour

In a crestfall of whiskers.

I hold you a moment,

Flourishing generation,

Then let slip,

Squeezed dollop of oil,

Primordial ooze

In a growling mill

That never shuts down.

Who could ever endure

Your vanishing?

Even as you vanish

Without sound or slick

Beneath coupling waves

To sprout, aeons later,

Sooty sapling, turgid root,

Your tail a swivelling T

Against a furious dusk:

Turner. Template. Tree.

My seal,

Dryad of metaphor,

You struck me

Before I could strike you,

A marine fever

That respects neither mind

Nor season,

But bewilders the heart

In the quiet of arid places,

A recrudescence of happiness.

Dowry

Like flocks the dust flew off the timbered hatch

When she sprang the hasp on the dowry chest

And plunged in, elbow-deep, her hand a perch

Swimming in mothballed waters, now a guest

Where once it ran host, rummaging for things

That keep slipping the fingers: a fawn brooch,

A ruched scarf, a blouse raging with sequins;

Until it gleans her wedding saree, scorch-

Ing as that day she left home in a spray

Of pulse and flower, the tears soldering off

Her cheeks and her father looking away,

His eyes drilling holes through a stubborn bluff

Estranging like this stranger, drift-boned, shy,

He handpicked for the apple of his I.

II

Now swatch by torrid swatch, I feel the dream

Unwind in her hands to be wound again

Years down the track by aunts who tack and seam

And smother her girlhood in silk, the skein

Reeling in their present as the past un-

Reels in mine. Amid the insinuating

Chatter, the laughter, I watch her snag on

A doubt, the future a nightmare drifting

Like crockery on a pitiless shelf.

How I want my dumb art to scream, to say:

‘Mother, swim out into your doubting self.

Plunge in against the current. Go astray.

I will your life to heave like a Van Gogh

Brushstroke, like verses, like poplar leaves. Go.’

Cane

Though it runs over the island in leaps

And bounds, no islander says what it is.

‘Prison bars,’ says the resident farmer

When pressed, his tone uncrimped by irony.

Others who grind the mills of prophecy

Talk without pause of molasses, bagasse,

Of all it’ll be when it’s not what it is.

Then there are the outsiders, the townfolk

Not in the know-how, who will compare it

To a phalanx, having read their history,

To an eclogue, having read their Virgil,

Although some among them will disagree,

The builder because he thinks of pillars,

The teacher because she thinks of margins.

But they too must lose it to some other—

Say a girl whose giggle makes it survive

In an orchard of desire, beyond itself

And that literal need to mark itself out.

Grain

An idle clasp, a relaxed swing, his arms

Snatch and heft the axe over his shoulder

Till, meeting the eye of itself, it turns

Ounceless as a wraith. Then it’s a boulder

Outsprinting eye, mind, his very muscles

In a downward run that smashes through sky

And estranging hill, and glazed apostles

Canonized for wresting brutes from the sty.

‘What lacks root?’ says the rippled sycamore

As the fanged axe splits it down the middle,

Splays it out like a moth. In the uproar

Of sparrows and chips, he cracks the riddle:

‘A stranger estranged by his own strangeness.’

Yet writ on your palm my wood’s graininess.

II

Ancient wood: cumbrous, hewable, cured hock.

Massive arboreal tome, how I love you—

Your alligator’s bark, your wrestler’s torque,

Your bailiff’s gravitas and breath of zoo.

Let them love the hot in you, the telos,

And hoard their bones against your bones, let them

Appraise a house, a hull, a Trojan Horse

In praise of you, but let my love affirm

What’s always forever to no purpose—

Like zephyrs vetching through a mortuary,

Like Greek myths related to Odysseus,

Like bonesmith’s art in a boneless country.

My love’s of your ancient venerable stock:

It goes right through the head to ring the block.

III

Woodflakes are flaking off like tuna flakes.

Axe droppings. Hot leftovers and leavings.

Chipped sunlight, terracotta. Exhumings.

You crouch amid ruins, remains. Your hand rakes

Up an art that shirks endings for random

Gleanings. Now here’s an ivory toothpick,

Late Ashanti. There, sheeny as garlic,

Some Renaissance tidbit, a severed thumb

By Cellini. Further, writ in magma,

Polynesian petroglyphs. To your left

Flotsam from a wreck. To your right tuna

Flakes flaking.

But all at once you’re bereft.

Leonidas is berthing. The light’s in gold.

Sixteen dead spartans in the tuna hold.

Flood

After a glut of heresy

We are believers again.

We worship mud.

We admired

The slick swerving run

Of the floodcat

But simply adore

The lumbering trudge

Of the mudox.

The floodcat

Was a thing of marvel

But outran

The marvellous

That abides in memory.

Whereas the mudox

Neither runs nor roars

But dumbly pours

Its fat protean bulk

Into wretched dreams

And exhausted boots

And open graves,

And champagne glasses

Crammed with gold dentures.

Until everything

Is a smother of mudlove:

A sprig of rose,

Wisecracks imported

From Scotland,

Sixty bolts of excellent linen,

And this town of course,

A muddy tract of skin

Which is the tract of memory

Composed of silt and silage,

A luscious, impervious heaven

Refuting the blasphemy

Of a single raindrop.

A Wishing Well in Suva

Let the tsunami come,

Let it come as an ogre in grey armature,

His forelocks in the sky.

To this town let it hum

A gravelly tune, and break

In the sound of wind through screes

Over and over and over.

Let it come exactly

At twelve, now or in the future,

When the trader is dealing a lie

To the worker; and the rake

Is drumming a lay on the knees

Of a gazelle who answers to Pavlova;

And the Ratu is consigning

All wilderness to woodchips

Over a hopsy lunch with a lumber

Baron from Malaysia;

And the Colonel is admiring

In a circus mirror his shoulder-pips;

And from his drunken slumber

A tramp is urging the tide to come in

Like scrolls of euthanasia,

Obliterating a lagoon

Where the egret grows sick on toxin.

O but let it come soon.

Let it flower like the 4th of July

And wipe out everything,

Except perhaps a tuft of fern

Adorning some crevice or crack

Where once the tern

Wove a nest from sea-wrack,

And an egg shook the world

(O shook this entire beautiful world)

With an inner knocking.

Nocturne

Everything weeps. This nib weeps.

The moon weeps. Weeps moonlight.

A hill weeps. As does the sky.

That blade of grass? It weeps.

It weeps in secret, tonight.

My earth weeps. Earth in my eye.

Pardon this grief. I have nothing

With which to sway your mind.

No wit, no image that leaps

And astounds with its leaping.

Just this grief, just this blind

Leakage of heart. A stone weeps.

Kingsford-Smith

I: Albert Park, 1928

He’d shaved a thermal lather off Hawaii

When they got wind of his mad intention

And felled trees, teak, kauri, the great ivi

Under which Degei pondered his creation,

Coiled in the lacework shade, a fossil of

Himself, bats fruiting in the boughs above.

The knolls were graded, apertures filled in,

Telegraph poles lowered for the approach.

Then they waited, planter, taukei and kin,

Twelve coolies, the Governor in his coach.

Around noon a nymph jabbed her parasol

At the sky and down she came like a swift,

Shearing a few trees, blowing up a squall

That stank of brine and carbon, and of myth.

II: Icarus

At the royal ball, dog-tired, goggle-eyed,

He ignored nymphs mooching about his wick

Like stricken moths, but nursed a gin and tried

Not to smile when they toasted his epic

Voyage in accents clipped and sedentary.

Later, he slipped out into the moonlight,

While a Planter’s wife murdered Tchaikovsky

On a church organ, and pondered the height

Icarus reached before he got waxed. Then

It struck him that all follies were classical,

Though one were both Smith and Antipodean,

Though one always verged on the cynical.

Next day a maid counting plumes on his bed

Saw him in the sunlight, half-man, half-bird.

diaspora and the difficult art of dying

The way of writing is straight and crooked

—Heraclitus

in the end is my memory of the beginning, a mixed brew of history and hyperbole, the sun’s chakra breaking up the earth of basti into six million jigsaw pieces, and the bo-tree catching fire at midnight by itself, and the koels pecking out the eyes of brinda the milch cow, and pitaji standing among the ruined fields of channa, weeping, and maji bent over the inflated moons of roti, weeping because he wept, and the immemorial debt to a greasy man of crisp dhoti and castemark whom we called maibaap, and my sister nudging the age of dowry, and i the eldest of three sons, sixteen years old and already corroded by despair, stealing away from home and village and province, never once looking at the moon grazing on the thatch of my nostalgia, walking by night and sleeping by day, until rivers no longer gave up their names nor roads their destinations, how many times i yearned to return to my village, ask me how many times my legs faltered during that terrible flight, but then i remembered the scorpions crackling in the wells of basti and the mynahs dying in the skies of basti, and that nightmare drove me towards i knew not where, maybe i sought work in a modest village, maybe i desired to fall off the edge of the world, maybe i was questing for ayodhya, shangri-la, el dorado, maybe, maybe, there are maybes ad nauseum, but my destiny was an arkathi with a tongue sweeter than shakkar, who sold me a story as steep as the himalayas, and his images had the tang of lassi and his metaphors had the glint of rupees, so that two days later i was on pericles, hauling anchor in the calcutta of my diaspora, and india slipped through my fingers like silk, like silk it slipped through the fingers of three thousand seven hundred and forty eight girmityas, and many things were lost during that nautical passage, family, caste and religion, and yet many things were also found, chamars found brahmins, muslims found hindus, biharis found marathis, so that by the end of the voyage we were a nation of jahajibhais, rowat gawat heelat dholat adat padat, all for one and one for all, yet this newfound myth fell apart the moment we docked in nukulau, because the sahibs hacked our bonds with the sabre of their commands and took us away in dribs and drabs, rahim to navua, shakuntala to labasa, mahabir to nandi, and my lot was a stony acreage of hell in naitasiri, where i served the indenture of my perdition, seasick, as if the earth here was no more than an extension of the sea, you must understand that nothing else bothered me quite as much, not the coolumber and his whoring with our women, not the fifteen hours of drudgery in fields that offended horizons, not the miserly rations of stale chawal, not even the sadistic lashes of sirdar ahmed kaffar ali, no, none of that bothered me quite as much as my illness, which came and went in purple swirls of nausea, and then one day i saw chinappa retching his innards over a bed of marigolds, his feet clearing terra firma by twelve feet and at once i knew we shared a secret fever, a month later twenty girmityas of uciwai had soared beyond the canefields to the utter dismay of the overseer, who ordered them back to the plantation with the aid of an inflamed crucifix, then docked their wages for trying to levitate all the way back to india, in fact my fever had turned into an epidemic of sorts, travelling from fiji to mauritius, from mauritius to trinidad, from trinidad to surinam, but though a platoon of experts was consulted in three continents and two hemispheres, though a flock of dispatches flew with the grace of carrier pigeons from csr to governor gordon to colonial office to india office to viceroy and back again, and though every quack in the empire came up with the placebo of a remedy, no antidote was ever found for mal de mer, and i was still defying gravity, then one night adaam aziz hanged himself from a rafter in bhut len, the soles of his feet were a tangle of cankered roots, a week later badlu prasad stowed away on british peer to the kasi of his memories, haunted by the putrefied soles of adaam aziz, but i was no devotee of yamraj and my dreams of india were marred by a brood of scorpions, and between the hell of girmit and the hell of basti was an ocean of alchemy, yes i stayed back because i had endured a sea-change and was no longer the i of my origin, what more is there to say, i served the girmit of my misfortune and leased a bhiga of land from the company and married sundaree, who in less than one year retched up all her memories of krishnas and tulsis and neems and diyas, thus letting the past stray from her mouth to form the present, so that in the end she no longer felt the surf rolling beneath her feet, while in contrast my sickness grew worse by the minute, which was odd since this was the great age of our communal imagining, tazia in fields and holi in streets, puja in mandirs and namaj in masjids, samajis in labasa and sanatanis in ba, maybe in my heart of hearts i knew we were imagining ourselves against the sahibs in order to supplant them, and around the taukeis in order to ignore them, maybe that was why my condition grew steadily worse, then one morning of pitchfork rains and slapdash winds i met ratu ilisoni viriviri, the tui-ni-vanua who roamed the margins of my land, my house, my vision, but who said i roamed the margins of his land, his house, his vision, thus began the shitty history of our misunderstanding, he was blind to my illness and i was blind to his terror of my illness, yet for the first time that night i dreamt of degei who scribbled fiji on a parchment of waves, and the gata of creation said that to be rid of my affliction i had to die into the vanua, the land, but like all muses the vanua accepts only those who invoke it by name, hence dying is an art like living, procured in the ripeness of time, safe to say i took his advice to heart and shaped from it my life’s philosophy, even as the plough struck the clods of freedom in the colony of our despair, and learning the art of dying i began to live through all my senses, they were the great years of my life because i began to discover what was already discovered, to name things as they were already named, i’d see but not hear a turtle dove until i said kurukuru, then its liquid-glass throat would bubble in the reeds of my soul, i’d smell but not taste an oyster until i said dio, then it would deposit the pearl of a flavour on my tongue, i’d hear but not feel the breeze until i said caucau, then it would stroke with a royal plume the castle of my skin, i’d savour but not smell a fish until i said ika, then it would fill my lungs with the breath of oceania, i’d feel but not see the storm until i said cava, then it would strike with lightning the domes of my eyes, so it was that little by little i went through another sea-change as my discovery of an oceanic present leaked into my memory of an indian past, until a time came when i could no longer think of machli, for instance, without thinking of ika, it was as if machli as word and idea and culture had never existed prior to ika, prior to my life on this archipelago, and yet one was forever inside and around the other, in short my act of invocation had made me visible and the island real, yes in the end i recognised the country of my banishment, i knew for instance that the third tide after the full moon brought in the king walu, that a hurricane was imminent when the doi flowered in march, that the flesh of niu karawa was more succulent in the dry season, with the result that i suffered less and less from my ailment and seldom left terra firma and then only by a few inches, and it was about this time that i sprang a taste for kava and shared mine with no less a foe than ratu viriviri, together we’d sit on a pandanus mat in the twilight of our decrepitude and he’d point to a flame tree and say sekoula and i’d point to the same tree and say gulmohur, and he’d reflect on what i’d said before conceding yes yes that is a better name, and i’d wonder if the names from my past were altering his present in the way that the names of his present had altered my past, o yes that year i ought to have died into the vanua, but instead we—grower and harvester and mill-worker—struck against the company and the sahibs sent in the native sepoys in frowning khakis to break up the hartaal, and hobbling in their midst was my friend ratu viriviri, yet i begrudge him nothing for they had us both bamboozled, taukei and coolie alike, yes it may be true that he joined the valagi to protect his vanua, it may be equally true that i fought against the latter to secure my freedom, but truth is a fickle sheikh in a seraglio of memories, so let me say that what happened happened, and afterwards i felt the land uncoiling beneath my feet and the surf growling in my eardrums, and realised that everything had changed and yet nothing had changed, and all at once i knew that i’d come to the end of my tether, and yet i’d never been further away from dying, and so it was that two months later, in the mercurial season of canefires and the sky a vulture swarm of black confetti, i dissolved into the grey rodent flesh of my only child mahadeo, and sundaree looked for me everywhere and then assumed that a madness had sent me back to the basti of my genesis, but all the while i was there in the hearth of her affection, learning to be unlike my runaway father, so that i grew up with an intense hatred of ratoons, you see, unlike the girmitya of my former avatar, i ascribed my condition to the whole damnable history of sugar and to the stolid gull of a peasantry, in a word, i switched professions and became a carpenter, yet i admit that mine was no potluck decision but one taken with a firm millennial end in mind, i had resolved to build a house that would withstand the oceanic tremors of my island, that would give me respite from my long and giddy life, and i remember on the day of my resolution as i dismantled the shack of my serfdom, kanti the trader arrived all the way from surat, his body trigged out in yards of homespun tornado, his feet shod in scarlet chappals, and he had a limp saffron jholi draped across his shoulder and an ashen moon thumbed on his forehead, and he asked me about my desires from under the shade of a raintree and i told him all, as if he were the shaman of my salvation, and he dug into his gunny sack and pulled out bolts and planks and beams and roofs, and in return i gave him the earnings from my bygone pastoral life, and once a month he came by to watch the wood grow into a bungalow, his jholi glowing with the materials of my slow addiction, and i thought he envied my lot in life while it was i who envied his self-assurance, his breezy gait and blustery talk, his freedom from mal de mer, his genius for six languages and feeling for one, and much more besides, then one day he took off his chappals and showed me his feet which were smothered in a network of ingrown roots, alive and squirming, as if sustained by some dark visceral logic, and i knew then that his sickness was worse than mine, that he was little more than the contents of his jholi and that, in less than one year, he would forsake the radha of his life to marry a stranger in the surat of his myopia, but that is the stuff of a different story, meanwhile i had moved into my new house with sundaree, my wife, my mother, who expired on the night i wed amrita, the daughter of a market vendor, but who refused to burn until her corpse had been duly sprinkled with gangajal, thus dying into india without acknowledging fiji, but unlike sundaree i lived on in the flesh of my undying self, sheltering from the sea in the fortress of my seclusion, then the theatre of war erupted somewhere beyond the horizon and i auditioned for a part, thinking that i may yet die into the vanua, the land, but i was escorted from the stage by a special force of berets in a state of delirium, and later amrita told me about my great relapse, how i had turned the colour of offal and droned out a mad litany of demands in exchange for my service, equal pay for equal worth for equal risk, independence for fiji, india, africa, expulsion of the csr from the known universe, unconditional access to valagi hospitals, clubs, schools and playing fields, crash course on imperialism for the local taukei, secure land tenure for peasant farmers and the like, and when many years later the grandson of ratu viriviri alluded to this moment of my treachery to justify his coup d’etat, i set about blaming my illness instead of probing his logic, in any event, i went back to the lair of my refuge after the shame of military rejection and pottered around the house while amrita sold dog-eared cabbages from a backyard garden to keep us afloat, then one dawn she found the lease of our undoing inside a dowry box and by noon a squadron of termites had invaded the house, and they shed their wings and chatted through the timber, and for some twenty years i heard the rumour of their carpentry, until in the end the house was reduced to a midden of talcum powder, but by then i had melted into subadra, my only daughter, and amrita had eloped to england with the cockney of her infatuation, yes amrita had shared my illness but felt that the remedy lay in physical motion, in not staying put, she was convinced that if the sea was the cause of her malaise then it was also its cure, that in time the caravel becomes the cradle so long as we stay afloat, but i was in love with the island of my torment, and so after the termites ate through my lease and ratu viriviri took back the land of his ancestry, i wandered from village to village for what seemed like an eternity, until one day i arrived in suva where everyone had my illness, even the taukei, but not a soul suffered from it, and it struck me that the denizens of the city had no need of roots because they had smothered the vanua in steel and concrete, thereby making of their illness a wondrous virtue, and they floated through the streets with a lightness of being and they chewed their food with a casual dispassion, and they had no need to stray from the city because the world came to them on trucks and ships and planes, and they procreated and laboured and expired as citizens, as those who were defined by what they had created and not by what they had inherited, and though i saw the moth of capital alight on the few and not the many, and though i understood its great sleights and feints and evasions, i was nonetheless attracted to its erratic flight through the raucous bazaar of my fascination and to its raw magic that transformed the humble lemon seller into a lemonade tycoon, but most of all i was attracted to the way it first made and then forgave the rootless soul, and so i settled down in the city of my third avatar and joined the local bank as a clerk, and that year when the sahibs departed with their union jack, i met and married the civil servant of my stability and together we worshipped the twin gods of thrift and industry, and together we built a house on the freehold of our dreams, and together we sent our son abroad to learn the ways of other cities, i thought i’d at last found respite from my long illness, i thought the city by its nature belonged to all citizens, but they came on the may of our unforgetting to claim for themselves the city we had all made, kaindia and kaiviti and kaivalagi, and once again i witnessed the miracle of mass levitation, though this time not in the remote plantations of girmit but in the desperate streets of suva, as teachers, toy-makers, lawyers, panel-beaters, civil servants, physicians, wholesalers, plumbers, tax agents, engineers, beauticians, batik-printers, among others, among many others, lifted clear off the ground and drifted across the reefs to the lands of their new diaspora, america and canada and aotearoa and australia, and i too felt the asphalt yield under my feet and saw jagan, my husband of twenty years, beckoning furiously from the streets below, but nothing could entice me back to earth, not my husband, not my city, not my history, nothing, and, in a few seconds, i’d breached a cupola of clouds and rounded the towers of sydney and dissolved into the body of my son, rajesh, who sat at his desk writing the first of his many stories about the island of his nostalgia in the hope that some day, when no one is watching, he will die into the acreage of his prose.

~~~

Citations: this selection of poems appeared in Diaspora and the Difficult Art of Dying, Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 2002.

Belle Ling is a university graduate from the University of Hong Kong, and later she has completed a Master of Creative Writing in the University of Sydney. She has a special interest in writing poetry. Her favourite novelist is Haruki Murakami, and her beloved poems are those which can capture insightful images with in-depth philosophical meanings.

Belle Ling is a university graduate from the University of Hong Kong, and later she has completed a Master of Creative Writing in the University of Sydney. She has a special interest in writing poetry. Her favourite novelist is Haruki Murakami, and her beloved poems are those which can capture insightful images with in-depth philosophical meanings. Melbourne-born poet, Peter Bakowski, keeps in mind the following three quotes when writing poems ‐ “Use ordinary words to say extraordinary things’–Arthur Schopenhauer, “Writing is painting”– Charles Bukowski, anand “Make your next poems different from your last”–Robert Frost. Visit his blog

Melbourne-born poet, Peter Bakowski, keeps in mind the following three quotes when writing poems ‐ “Use ordinary words to say extraordinary things’–Arthur Schopenhauer, “Writing is painting”– Charles Bukowski, anand “Make your next poems different from your last”–Robert Frost. Visit his blog