“Sputnik’s Cousin” by Kent MacCarter reviewed by Dan Disney

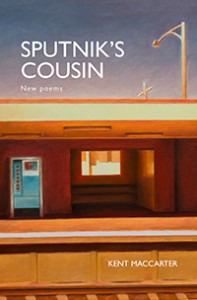

Sputnik’s Cousin

Sputnik’s Cousin

by Kent MacCarter

ISBN: 9781921924675

Reviewed by DAN DISNEY

If you are looking for narrative sensibilities or lyric sense-making in a narrow sense, then Sputnik’s Cousin is not for you. About as far out as its Russian satellite namesake once was, this is a book of astronomically strange experiments delivered as ‘poems and non-fiction’ (back cover). MacCarter’s texts are a kind of otherly reportage fed through deviant, garbled syntax, and these little machines of momentary expressive orbit are built to record the fetishistic weirdness of their human subjects. Indeed, and as if Sputnik-ing from the sidereal, MacCarter’s excursive and idiosyncratic inventions sputter heartily to their own trajectories; this is literature but not as we have known it.

The book is organised into seven discrete packages of high-octane oddness: in Sputnik’s Cousin we find prose, faux-sonnets, prose-poems, strange verse, even an historical melodrama. ‘Fat Chance’ is pure gallows humor, an enumeration of unexpected death which has less to do with the darker satires of, say, Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 or Vanessa Place’s Statements of Fact, and is more like scrolling randomly through liveleak.com scanning for Darwin Awards nominees; ‘Pork Town’ is a Bataille-esque psychogeographical romp across the patina of Melbourne’s inner-western badlands, and both these non-fiction sections offer generic (but not stylistic) variation from the poems. ‘Stencil’ is a suite of 23 non-accentual ‘sonnets’, ungainly but measured, mostly rhyming; here, we may be forgiven for thinking MacCarter is lapsing into his own version of neo-surrealism. The eighth ‘sonnet’, ‘Geiger-Müller Counter’, seems at least initially to want to party hard with the oeuvres of, say, James Tate or Russell Edson –

A little pony of a man with a tiny pony brain

trots up floor after floor … (42)

But unlike the willed madness of surrealism first championed by André Breton in the 1920s and taken up by Tate et al toward the end of the 20th century, MacCarter is up to something more state-of-the-art than playing out processes capturing (as Isidore Ducasse framed it) a ‘fortuitous meeting, on a dissection table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella’. MacCarter’s anarchic fervor is instead sustained by distinctly contemporary experimental impulses –

detecting blocks, an office tower

the jaundiced shade of gristle Geoffrey Smart wars, reconsiders

chews over, measures. A centre freeway oyster blade Vein

this man’s contraptions pulsate along clot hot in kitchen space

tallying ill the zap gone microwaves serve wet tantrums

at employee-meat like a tennis star’s frippery of spectrums

re-heated from the United Colours (sic) of Benetton’s face …

(‘Geiger-Müller Counter’ 42)

Such is the sheer quantity of chopped and mangled imagery in ‘Stencils’, and indeed throughout this book, that instead of rocket like missile-missives, these poem-vessels propagate a ‘rudiments of barnstorming’ (40) more akin to a poetics of image-as-displacement, or the recording of random detritus. Perhaps echoing Kenneth Goldsmith’s notion of ‘language as junk’, these texts are remnants and remainders, repurposed in a cut-up and readymade mode: a new spin, then, on what theorist Marjorie Perloff brands as récriture (that is, literature as recycling). And it is this that makes Sputnik’s Cousin such a difficult but welcome arrival.

Rather than staging surrealistic mayhem, MacCarter’s poems speak from a different order of assemblage; so often the poems are located somewhere between récriture and reconnaissance, played out in this collection as a repurposing of random snapshots, a mixing/ switching of registers, and the recalibrating of canonical forms. In ‘Smoke Odes’, a multiply-epigraphed suite in which a perhaps-augmented MacCarter nods to his influences (literary and elsewise), we see just how many filters overlay the viewfinder –

Oddity, your small army

of guerilla cosmopolitans and pomegranate cleverness

keeps our gossip sugary and tasteful

in forums

and under Magritte’s derby

cluster our prized ruby gems

… Neil Gaiman, Osamu Tezuka, Eddie the Eagle, Tom Baker, et al

(‘Kissing Frank O’Hara [not on the mouth remix]’ 23).

As promised on the book’s back cover, these texts ‘hum a progress charged by humanity’s witless pursuit of technology and civility’; Sputnik’s Cousin charts a progression from Darwin’s Beagle (87) to near-future potentialities and, at heart, these meditations (at times hilarious, at times confronting, at times outright confusing) promulgate a particular and peculiar worldview churned through eccentric grammar – gerunds, denominal verbs, split infinitives, subjunctives – swirling into vertiginous non-unity. Prosodically then, if after Pope the sound must seem an echo to the sense, these poems are loud expositions of a world falling to pieces.

MacCarter writes how ‘I swear at times I know’ (130), and this book is suffused with deliberately destabilised processes of deliberation. The texts are always fast-paced and straight-faced, but also cockeyed – the poet ‘will oilspill/ your salted waters’ (16), and ‘tip the cup for sip’ (16); these are not so much ‘plots of gibberish’ (125) as febrile examinations of meaning-making (and where that has got us so far, circa 21c.) by a poet who seems altogether at ease as an outsider expressing the contours of exile to his ‘fellow travellers’ (this the literal translation of ‘Sputnik’) –

corroding its circuitry, the hairdos of maniacs

cut to its verb

to be

remains. What remains (?)

of the grammar and me

oxidize behind

arse factory

supine from its unstoppable whispering

of why?

(‘Mergers/ Acquisitions’ 93)

MacCarter is exploring expressivist possibility here, and indeed experimenting with the plasticity of his material (that is, language); this post-po/mo jongleur is a free range radical stuffing his texts with images not so much fragmented as purposefully blurred. These are snapshots of an existence undertaken at velocity where even affect is bleary, vague, and out of focus: ‘I had bang lick wow they was abject’ (134). MacCarter’s is a savvy but also risky experimentalism, and by intentionally defocussing the image he will certainly be misread by some. But the great value of Sputnik’s Cousin is that it is not derivative (despite the many references to literary influences throughout the book), but instead opens intelligent new heterotopic possibility.

Indeed, Sputnik’s Cousin is a laboratory strewn with sensible inventions, where precision seems to have been intentionally deprioritized, and the view defocused to imitate the speeds of contemporary existence. The broken syntax echoes current conditions of consciousness – multitasking, distracted, spanning surfaces without the depth-experience of connection – and these poems are plausible models, a collection of ummwhatwasIsaying sayings. When surveying the persistence of older modes of the lyric impulse, arché-Conceptualist Christian Bök tells us how he is ‘amazed that poets will continue to write about their divorces, even though there is currently a robot taking pictures of orange ethane lakes on Titan’. File Kent MacCarter’s book under ‘feral’ or ‘HAZCHEM’, and expect the dizziness that can happen when accustomed modes of understanding shift, or the vertigo of non-comprehension when a mutant genus first arrives. Sputnik’s Cousin is voicing the everyday in ways that are lyrically, indeed generically, challenging: a feistier means of having the tops of our heads taken off.

DAN DISNEY teaches with the English Literature Program at Sogang University (Seoul)