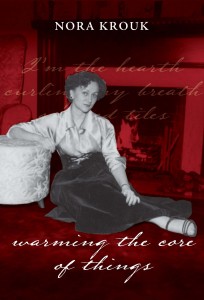

Brook Emery reviews “warming the core of things” by Nora Krouk

by Nora Krouk

ISBN: 978192166543

Reviewed by BROOK EMERY

Over the last few months, while all the wise futurists have been forecasting the decline of the book and the ascension of the virtual word, I’ve been thinking about why I’m so attracted to books, specifically to poetry BOOKS, to collections of poetry. I’m not much good at reading poems on the web and I often feel dissatisfied when I read single poems by various authors in journals and anthologies, even in hard copy, even in canon-making anthologies such as The Norton. To me, in these formats poems seem to be isolated, un-contextualised, orphans. I find myself reading one poem after another subconsciously saying things like ‘Oh, that’s not bad’, ‘Yeah, I quite like that one’, ‘There’s not much in this one, is there?’ and flipping (or scrolling) to the next one without really engaging with the poems or feeling involved. I find myself hanging out for a book of poems by the one author so I can get some sense of narrative and coherence, a feeling that the poems speak to each other and enrich each other, a sense of the voice, and personality, and world experience behind the poems.

These considerations came back to me strongly as I was reading Nora’s warming the core of things for the first time. This is a book which invites you to enter and share a life. It is a book which, poem by poem, builds into a unified and challenging consideration of what has been observed and experienced over many years. It is a book in which the overwhelming feeling is ‘warmth’, literally and metaphorically. Such warmth is doubly attractive and welcoming at a time when a lot of poetry is cool, detached, clever, and sometimes seems to have lost touch with that really basic responsibility of poetry to reach out, to connect, and to explore what it is like to be human in our thoughts and feelings.

Warming the core of things is a book which is intimate, confessional (if you like). It celebrates the personal, the familial, and the emotional, it concerns itself with the relationships between people over time. It makes me think of lines from Jack Gilbert’s poem, ‘Highlights and Interstices’ where he writes ‘… our lives happen between / the memorable. I have lost two thousand habitual / breakfasts with Michiko. What I miss most about / her is that commonplace I can no longer remember.’ Like Gilbert, but in a very different way, Nora raises the everyday to moments of insight and appreciation. And like Gilbert, despite what he says about himself, Nora does remember both the ordinary and the extraordinary. Two of the things she and Gilbert remember and feel acutely are love and loss.

The first section of Nora’s collection is titled ‘In Memoriam’ and begins with a delicate poem to her husband Efim who died in 2008. The poem ends with the simple, dignified statement, ‘I miss you’ but this section is no simple, romanticised portrait of a long marriage and the death of a partner. It is clear-eyed, emotionally honest and vivid in its realism. It notes the tensions and ironies and ordinariness in lines such as, ‘she hates to leave him alone / yet itches to step outside’ (‘They are together most days’), in the white chair that waits ‘brazen with coloured cushions’ (‘Slumped in a chair’), in the ‘bare bottoms and other bits’ and the ‘inmates with anguished eyes / [who] search for themselves / [and] stumble over the shards’ (‘Ward 15’). The section expands to take in other deaths, other inevitabilities, and below the surface of them all are the perennial human questions, ‘Why?’ and ‘Couldn’t it have been different?’ Usually the questions are implied but sometimes they are explicitly stated as at the end of the poem ‘Blue Doona’ when Nora asks, ‘Couldn’t you just live?’ It is worth remembering that question from an early poem when you come to the last poem in the book. I’ll say something about this later because it reveals a great deal about Nora’s vision. These poems, these wishes, are moving, touching, but Nora doesn’t live in fantasy, she knows that what happened has happened and nothing can change it or take away the grief because, as she writes in ‘Birthday’, ‘Love is the most pitiless feeling of all’. To really understand the import of this statement, to unpick the relationship between ‘pity’, ‘pitiless’ and ‘love’, you not only have to read the whole poem but the whole collection. Only then will you appreciate the wisdom and emotional intelligence of this collection. Nora is a participant in these poems but she is also the thoughtful observer and interpreter. These are poems in which the border between life and art is more porous than is often the case. It takes courage, assurance and depth to be able to write, ‘My dearest dearest difficult / husband My love’ (‘What should I do’).

The capacity for love leads to an indignity at injustice, especially the injustice done to the individual by the impersonal forces of history. It is there explicitly in some poems and is the context in which the personal happens. Nora has lived a memorable life and she remembers and can see, at this distance, things as they were, that ‘The good times in Shanghai / [were] a 20th century masquerade / as the world burned’. Nora also sees, for example in the poem ‘For Leon K’, how the effects of not knowing – ‘What did they do / before his boots were filling with blood’ – can reverberate through the decades and continue to hurt, even cripple. Nora is witness and rememberer of a father who had to break with his Polish past, of a mother ‘buried in Chinese soil / without a headstone / during the Cultural / Revolution’ (‘A short visit’), of massacres in China, experiments on humans in Harbin, of atrocities committed in war. That the personal is the political is a bit of a silly phrase but Nora’s poetry reminds us that we are all part of events that seem to have happened ‘over there’ or ‘back then’ or to ‘someone else’. Reading these poems we are reminded that no man (no woman) is an island.

Warming the core of things changes gears somewhat in the second section which is called ‘Renewals’. Here the warmth and love which were manifest within the sadness and grief are expressed in a sensual joy in beauty and in a determination to appreciate the bounty of nature. Here the poems are overflowing with wisteria, lavender, roses, gardenias, asters, food, friends, and the warmth of the sun. In the first poem ‘A smile is hovering over our street’ (‘A young woman’), in another ‘this day is / a glob / of honey / a pouring warmth’ (‘Dust on the silver chimes’), in another ‘ Like that butterfly / drunk / on sun / I claim it all: My sun!’ (‘Like that butterfly’), in another Nora is ‘… grateful to Fate / for landing in the sun’. (‘Memory’), and in ‘Shanghai Sydney’ Nora is ‘moving through an amazing puzzle / picking a piece / here on my palm / wishing I knew a psalm / or a prayer of thanks // For everything’ (‘Shanghai Sydney). This section of Nora’s book transforms as well as renews.

If warmth and wisdom are the two dominant qualities of this book, it is the voice of the poems which makes them so attractive. Nora often jokes that her Russian typewriter mischievously makes syntactical or idiomatic mistakes in her poems or, perhaps, even writes the poems without her intervention. I don’t quite believe her because I hear her voice in so many of the poems, in little statements and questions, especially questions. I constantly hear Nora asking herself what she knows, what she has learnt, what she then believed and now believes, what she can do about fate, the inevitable. This is most notable in the third section of the book, ‘Transitions’ in which Nora has a number of conversations with God, humorously wonders about chaos theory and deals with a number of more or less philosophical issues. So many of these poems have a quality of consideration and reconsideration which is made explicit, appropriately near the end of the book, in the poem ‘Once I could plan or act’. This is not dogmatic poetry but the book does grope towards tentative, provisional answers. This testing of ideas can be seen, for example, in Nora’s identification with the sasanqua in ‘Sasanqua in May’

I know the feeling.

A similar hard-won understanding or, at least, acceptance occurs in the poem, ‘Discussions about God’ where she writes ‘My slender beautiful / jacaranda comes / into bloom slowly / It blooms and sheds / sheds and blooms // Is this the answer?

For me, a baby boomer born and raised safely in Sydney who has not known depression, revolution, war, dislocation, internment, expatriation or, on the other hand, the high, fashionable life, who has taught history but didn’t live it, these poems make me realise how little I know, how little I understand, how little I have experienced.

Here is where you have to remember that early poem.The last word in Nora’s book is ‘live’ with an exclamation mark and that feels appropriate and significant to me. As does the epigraph to the last section of the book, a Ukranian saying, ‘Wishing you good health, warm bread, and peaceful skies’. In its entirety, warming the core of things is full of life; it endorses and celebrates that Ukranian saying.