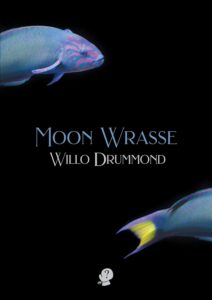

Misbah Wolf reviews “Moon Wrasse” by Willo Drummond

by Willo Drummond

Puncher and Wattmann

ISBN 1922571679

Review by MISBAH WOLF

When I first picked up Willo Drummond’s debut poetry collection, Moon Wrasse, I was torn between a deep panic of knowing I wanted to become mixed up in the muck, blood, and bloom of the work and wanting to also turn away from the words. Words are spells. Words are little invisible ties between what is captured and what is lost, and somehow, as if by magick, portals are opened for us to walk through. In a true sense, this is an offering from Drummond of a portal of initiation—you choose which kind—one you’ve already been in parallel with, one you have no memory of, or one you care enough to walk along with to experience and become more completely human.

I opened the book to the poem ‘Seed’ which, in a sense, introduces what I see as a quartet of work. I read;

At this season’s out-swelling

after the mangrove moon

she sets her grief in a small seed pod.

(7)

I, myself, had been dealing with ‘unexplained infertility of ten years, and I wasn’t ready to read it, but the book called out for a conversation with me. I recognized it within my own immediate framework as a book of invisible connective tissue, a witch’s book of shadows, both literary and psychic, between the dead, the dreaming, grief, the acute attention to the breath of things and the indexing of transformations. This is a book where surfaces appear deeper once immersed, where continual intertextuality adds further dimensions, and no energy is ever lost since all is transmuted. A pause must be taken, and a return, like a Joseph Campbell Hero/Heroine, is undertaken;

She’s looking for

a future to enframe the past

as it exceeds

it. Flickering familiar

like the pulse

of being needed.

(7)

Reading this work, I was able to chart a ship in the shadows of Drummond’s glorious book—through my own grief over childlessness, my estrangement from others/lovers, my deep love for ecology, for the mud and muck of various things I have lost, found, and re-imagined. These things grow in Drummond’s poetry through mud and shadow like mother mangroves, endangered blooms, and conversations with visceral transformations under ‘dappled light’. (60) Such love is to be invoked in the poem “Moon Wrasse” where the narrative etches through the shifting cycling as a lover/other/self that is;

here, moving in

our translucent

cocoon

‘self-made’ and safe

as houses— (60)

It is an homage to great love transforming and witnessing the beloved’s

new lucency—

clear as the blue

of your new man suit

sweet as the day

true as the day (60)

This enamoured lover/narrator bears witness/encourages and celebrates this alchemical corporeality with tender reassurance in this delicate liminal space,

holding hands

like younger lovers

in a film

in a dream.” (60)

The shape of the month as I read this work was also colored by other books at the same time. Fitting for such a book that plays, converses, and returns to dialogue entries, quotes, and habits of other poets and writers. Rest assured, Drummond includes notes about particular moments, words or passages from other writers in this book to show how interwoven and entangled this book is with others’ work. In The Childless Witch, Camelia Elias says: ‘The age we live in is, indeed, no longer an age of lamentation. We lost that art long ago’ (Elias, 2020). The reason I’m including this quote from Elias is that Moon Wrasse has developed a very delicate language of lamentation, with images of ‘striking,’ ‘scraping,’ and ‘digging,’ further propelled after Louise Glück—as in Drummond’s ‘The Act of Making,’ (11) using techniques of alliteration, words beating against each other, switching to words that require the tongue to be pushed gently through lips—there is a feeling when reading this poem and many like this, of incanting. In ‘The Act of Making,’ Willo Drummond employs a rich array of poetic techniques that enhance its incantatory quality. Vivid imagery and sensory language, such as ‘gardens fecund with memory'(11) and ‘imagined blooms heavy with the scent of hope,'(11) create an immersive experience, while enjambment ensures a seamless flow between lines, propelling the reader forward, as in

.How can you bear

so many imagined blooms heavy with the scent of hope

let go? (11)

The use of repetition and parallelism, like ‘day after day,’ adds musicality, and the alliteration and assonance in phrases such as ‘fluffed intentions’ and ‘solitary bees’ create pleasing sound patterns that my mouth wants to vocalise. Caesura introduces rhythmic breaks for emphasis/division/rupture of grief;

Unwomanly. Bent queen

brimful of love shame with nowhere to dig

in (11)

Also, the sharp juxtaposition of contrasting ideas, such as ‘love/shame’ and ‘hope/let go,’ deepens the poem’s emotional impact. Symbolism, unconventional syntax, and strategic line breaks contribute to the poem’s unique rhythm and pace, while personification and metaphor, like ‘remembrance scratches your knuckles’ and ‘bees hover, uncertain,’ imbue the poem with lyrical depth. These elements combine to make Drummond’s poem feel rhythmical and lyrical, making me want to read it out loud. And I do speak them and it is a pleasure to let the words slip and pause between my teeth and tongue.

We can look further into such poems as ‘Note to Self (in Novel Times)’ that inscribes like graffiti on an ancient/new wall to a future/past/now self, on a fridge pinned up by magnets to;

Remember to love

the world. Love

the wailing, rolling world;

the air; the wildness

of wind lifting a million kites

of change (72)

Such a poem circles back through voice, through lamenting, through oracle (as Earth) as change always present to call one back home. In The Childless Witch, Elias also reframes such a being as ‘able to cast a powerful spell of movement, a movement that goes from trembling, to dance, to the use of voice, the oracle and a state of grace’ (Elias, 2020). Looking through Drummond’s book, these states of ecstatic magic—shadowy and bright—are evident in the language and invocations that run rife throughout this collection. There is a language of lamentation here, as previously suggested—of that which will not grow among the commonly seen, and offers instead the witch’s second sight such as in the poem ‘Ways of Seeing.’ This narrator is pensive with ‘portents’- where moon cycles are traced and named;

While others turn with such precision,

radiant orbs—content

filled—I dream of conjunctions

luminous alignments

stackings of hope (20)

This second sight seems always pensively aware of the delicate nature of life in ‘The Art of Making’ that we as readers intrude/bear witness/are gathered round to see ‘Somewhere, a ghost orchid blooms’ (12) This rare orchid/child/being blooms only once a year, pollinated by mimicking male sphinx moths deep in forests where it sucks the moisture from the air.

With this invitation from Elias—’trembling, dance, voice, oracle, and grace’ resound through Drummond’s work. There is even a further complexity established by which Drummond records in her notes at the back of Moon Wrasse that the line from the poem ‘Seed’,

where what cannot be

is (8)

gestures to Jennifer Moxley’s claim that ‘lyrical utterances record voices structurally barred from social and political power.’ (Drummond, 76). This first poem is set adrift from the four sections as a poem in motion, of coming up from elsewhere by will;

here in the lyric tense

she stills to witness

each furred pod/

gain its wild purpose—’ (7)

This feels like an invocation to voice, to the tiny seed to speak its will, to inscribe and to create. Again, a voice unheard/heard is set in motion in ‘Sail,’ where the other’s silent voice is;

voice, a gaping mouth, calls

from a crack in the world: desolate

wind, sweep my knowledge

into oblivion, drop me back

into the well. (21)

Read it aloud, read it softly and it could well be the words of shamed/guilty/lamenting Medea, such a misunderstood and maligned witch, also a favourite childless witch of discussion for Elias. (Elias, 85)

I have enjoyed framing Drummond’s work as part of a Quartet, a story perhaps like a cycle connected in four parts, likened to the four major phases of the moon—the new moon, the first quarter, the full moon, and the last quarter—because so much of the work makes invitations, invocations, and references to the moon. In Drummond’s section ‘The Art of Losing,‘ ‘Of Finding and Not Finding Levertov,’ ‘Forming and Transforming,’ and ‘Arriving,’ why not take this as a template, traversing phases of the moon? Considering that in my reading, I felt poetic tidal shifts under the witch’s tools of moonlight and water, whether inscribed as bodies, mangroves, fish in moonlight, or rare blooms sucking at the mist. I enjoy mysteries and puzzles and esoterica, so I have dug into this deep pleasure in making these connections through the language or merely literary pareidolia. But there are clues to make such connections, such as mention of the ‘spun to song of sun played at waning moon‘ (61) in ‘A Promontory/A Memory,’ and, of course, the poem ‘Moon Wrasse’—the fish that changes sex to mate and has a crescent moon on the caudal fin, the energy of such seems to suggest a letting go of what has been and finding hope in a ‘translucent cocoon'(21) moving towards the new moon. The new moon is, of course, the dark unseen moon. It is the place that calls for presence and to explore the unseen, and I pose that this is the beginning phase we enter from the start of the book, with poems that seem to scry into the unseen. Considering the first poem ‘Seed’ moves from the lines;

In waning luminescence

on the aqua-terrestrial shore

she trains her eye

to velvet vivipary

on very salty water

She’s looking for

a future

to enframe the past

as it exceeds it. (7)

It is the entrance towards the darkness of the new moon in the first quarter ‘The Art of Losing.’ In the new moon phase, there is no visible moon in the sky, and it is the time to explore the unseen, to call for presence, and to stretch the grief unfathomable into song and poetry.

The first poem of this quarter, “The Act of Making,” is indeed what Camelia Elias calls ‘the lost art of lamentation’(Elias, 15), again inscribing vividly with a question;

How can you bear

so many imagined blooms heavy with the scent of hope

let go?” (11)

Set behind this poem is hauntingly Glück’s ‘The Wild Iris’ (“Hear me out: that which you call death I remember”) like the wild Iris, reborn, returning from dissolution to ‘find a voice’—here Drummond masterfully extends the deep mystery of Glück’s poem of death and rebirth, and continues the esoterically charged moment to look for portents, to have knowledge of the rare ghost orchid ready to be born.

In this first quartet too, ‘Up to Our Knees in It’ explores the unseen mother mangrove beneath the surface, extending and connecting, living anywhere despite the ‘cinema seats and soft drink cans‘ (15) thrown into the waters.

Furthermore, Drummond’s poetry, particularly in the sequence ‘The Rilke Index’ and ‘Open Secret,’ showcases a profound engagement with the poetics of Rilke and Levertov. By using index items as titles and integrating verbatim citations, Drummond creates a rich intertextual dialogue. This approach pays homage to Levertov’s method of personal indexing and underscores Rilke’s enduring influence on Levertov’s work, which in turn feeds and nourishes Drummond’s. The titles and substantive material, marked by italics for Rilke and inverted commas for Levertov, reflect a meticulous synthesis of response, citation, and allusion (Drummond, 2021).

Central to Drummond’s poetry is the theme of attention and participation, echoing Rilke’s poetics. In ‘The Rilke Index,’ phrases such as ‘True singing/ is a whispering’ (35) and ‘It hums along the avenue of original grief polished as a stone’ which highlight the importance of quiet, attentive engagement with the world (Drummond, 2021). Similarly, ‘Open Secret’ uses the imagery of a Peltops singing her inwardness to suggest a deep, participatory observation of nature.

Drummond’s work exemplifies Rilke’s Ding or thing poetics through its focus on sensory, concrete experiences. The detailed imagery in ‘The Rilke Index’ and the tangible descriptions in ‘Open Secret’ underscore the importance of observing and interacting with the material world. This attention to the physicality of things aligns with Rilke’s belief that true insight comes from an intense, participatory observation of one’s surroundings.

Reflecting deeply on the nature of creation and the self, Drummond’s poems reveal a continuous journey of self-discovery. ‘The Rilke Index’ and ‘Open Secret’ meditate on the interconnectedness of self and creativity, suggesting a composite identity shaped by various influences. Drummond’s imagery, such as ‘the owl afloat, the white egret’ and ‘the blood, the plough, the furrows made,’ captures the essence of seeing with ‘second sight,’ a deeper, intuitive understanding of the world (Drummond, 2021). This second sight is the sight of the witch, the seer, the being that dares, even when nothing necessarily will come of it—to look and to record presence/absence. Not only is second sight present here, but also the Owl—the totem of Hecate—Queen of Witches, and the action of tilling the land with blood and earth, much like the ingredients for a spell.

Willo Drummond’s poetry collection extends the poetics of Rilke and Levertov, emphasizing immersive conversations with the world—the unravelling power of careful observation and recordings. This work also creates carefully layered, intertextual dialogues. These inscriptions highlight the profound connection between self/other, the environment/body, second sight/inscription—all of which is the (witch’s) work of invocation with moon, of birth, death, rebirth, of longing (and the language of lamenting), and a complete presence of ritual observation, a conversation with invisible/visible forces transmuting. This book is an homage to love and magick and finding ways to reinscribe very necessary and vital voices and existences that have slipped/been silenced/written over/unpublished/forgotten. But it is also more than an homage—it is script that spells out the nature of time, looks closely at the Fibonacci spiral of bodies in presence with each other, of lamentation and joy rupturing through—detailed and woven with the echoes of other writers and poets, insistently in deep relationship to ecology, to the unseen dance of interconnection, such as the spellcasting in ‘All of it’ as ‘an ecology of selves’ (67) which with tremulous blooms/hands/words/voices reimagined worlds, relationships and love.

References:

Drummond, W. (2021). The Rilke Index. TEXT Special Issue 64: Poetry Now, eds. Jessica L. Wilkinson, Cassandra Atherton & Sarah Holland-Batt.

Drummond, W. (2023). Moon Wrasse. Puncher & Wattmann.

Elias, C. (2020). The Childless Witch: Trembling, dance, voice, oracle, grace. EyeCorner Press. ISBN 978-87-92633-57-6.