Jenny Hedley reviews “Icaros” by Tamryn Bennett

by Tamryn Bennett

ISBN 978-1-925735-56-7

Reviewed by JENNY HEDLEY

The use of medicinal plants or herbs originates from Indigenous knowledge systems which predate colonisation by thousands, or in the case of Aboriginal pharmacopeia, tens of thousands of years. Phytotherapy, a science-based medical practice first described by French physician Henri Leclerc in 1913, uses plant-derived medicines for prevention and treatment of ailments. Today, industrial pharma hacks plants’ intrinsic biotechnologies for maximum profit, producing pills and potions engineered to ease mental and physical maladies. What has been overlooked by the dollars that be (aka extractive capitalism) is the use of traditional plant medicines for diseases of spirit.

Tamryn Bennett’s Icaros sings into that supernatural vegetal space of mystification, ritual and holistic therapy. ‘Icaro’ comes from the Quichua verb ikaray: ‘to blow smoke for healing’. Icaros are traditionally sung by curanderx or shamans during plant ceremonies which originated in the Amazon basin.

Medicine songs

ancient as jungle

we’re passengers of the plant,

the dying, deaf and addicted. (32)

Not to be approached lightly, ayahuasca ceremonies demand discipline, respect, and abstinence from sex, drugs, alcohol, salt, sugar and some animal products. Set, setting and intention must be considered.

Wrapped in net

Ayanmanan asks your intention

holds a fuming stone

and a basket of shadow.

chhhh chhhhh chhhh

chhhh chhhhh chhhh

Follow the chakapa

rattle of ritual

Drink the vines to know

the pattern of all things. (32)

During ceremony, the Banisteriopsis caapi vine interacts with the leaves of the Psychotria viridis shrub to produce beta-carbolines that restrict the ability of a person’s monoamine oxidase enzyme to degrade the N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) present in the sacred vine. The DMT acts on the central nervous system, allowing people to access a state of nonduality or oneness.

This is where amnesia and healing

begin, along the worn path

a wreath of hedera helix. (22)

Bennett’s spirit songs carry us into this alternate reality, performing a pas de trois between English, Spanish and verdant language where plants speak and we listen. In Covert Plants, Baylee Brits and Prudence Gibson define ‘plant writing’ as being receptive ‘to sentience, sapience, and forms of life that are distinctly botanical’ [1].

This Is Your Mind On Plants author Michael Pollan writes, ‘Psychedelic compounds can promote experiences of awe and mystical connection that nurture the spiritual impulse of human beings’ [2]. Clifford Pickover, who received his PhD from the Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry at Yale, hypothesises that ‘DMT in the pineal glands of biblical prophets gave God to humanity and let ordinary humans perceive parallel universes’ [3].

If philosopher Simone Weil were inspired by herbaceous delights and ‘[f]our billion years of infinite / combinations’ (21), rather than the Christian God, perhaps these are the aphorisms that would flow:

How do you want to die?

That’s how you must live.

What are the seeds in your heart?

That’s the tree you will become. (17)

She might channel this ‘voice from the other world’ that ‘tells us to taste / the deities of dirt’ (45), to ‘remember where you hid the key’ (79):

when the world gets too heavy

lay yourself down

be still a hundred years

let go of the paper lives,

what could you carry

all these seasons anyway?

breath, sun, rain…

none are ours to keep

leaves are lessons of release (29)

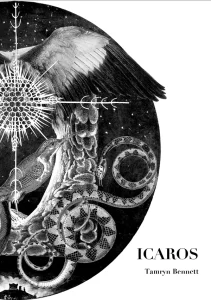

Illuminated by artist Jacqueline Cavallaro’s otherworldly paper-based collage, compressed from three dimensions into two, Icaros extends the collaboration between poet and visual artist as exhibited in Bennett’s debut phosphene, published via Rabbit Poetry Journal’s Rabbit Poet Series in 2016. In both volumes, the visual amalgamation of figurative fine art with zoological and botanical sketches decentres the human, imbuing the vegetal with eyes that see. These uncanny, surrealist compositions of art and text, whose title-page glyphs suggest a relationship between story and stardust, or perhaps the origin of language, invite the reader to open themselves to ancient ways of knowing. Bennett presents a reality where everything living derives from the cellular—a ‘fistful of galaxy reassembled on shore’ (19): it is all a matter of scale or time.

In the introduction to phosphene, Bennett describes her poems as ‘fragmented elegies’ and ‘prayers for the wind, for buried cities, for the invisible and the sacrifice’ [4]. She takes us with her as ‘at the temple of letters’ (4) she ascends ‘two thousand stone steps / into cloud’ (6). Where her debut poetry collection invites a collaboration with her ‘plant symphony’ project co-artist Guillermo Batiz, whose Spanish translations precede, follow or are interwoven with Bennett’s, Spanish seeps seamlessly into her sophomore collection. Each method lends a sonorous quality to the text: in phosphene it presentiments, echoes or proffers a call and response; in Icaros, bi-linguistics perform alongside onomatopoeia, the hissing of fire, the incantation of song, a rattle’s percussive hiss.

In Icaros, Red Room Poetry’s artistic director, Bennett, who received her PhD in literature from the University of New South Wales, remembers the women who were burned at the stake, for those whose ‘Plant knowledge comes with a price, / hide it or be set ablaze’ (40). She acknowledges the creep of colonisation, ‘Languages leaving, / little extinctions in the dunes’ (68). She walks us through preparations for ceremony—‘we pick sage by barbed wires / weed plastic bags from prickly pear’ (48)—and into ritual itself:

Palo santo on the abdomen

to cut the cords of attachments,

for the ones that left

and children who were not.

Collect kindling to reawaken. (49)

I am a little bit obsessed with the form of Icaros. Where phosphene presents four poems which sing, reverberate and refrain across a number of pages, Icaros divides a series of poems into four sections: Marrow, Ritual, Remember and Matter. While each section’s ten to seventeen poems are titled in the contents, the titles emerge directly from the text and are indicated in each poem’s body by bolded font. This integrated technique permits an uninterrupted reading of each section as if listening to a chant or Benedictine chorus, creating a sensation of ongoingness evocative of oral storytelling, where shadow and light play tricks of perception around flickering fire.

In Art Objects, Jeanette Winterson argues that artful writing demands that the writer’s breath be evident in the cadences of lines; in rhythms, breaks and beats shaped together as if sung; in a pulse echoing that of the writer’s body [5]. Slow down, is Bennett’s injunction. Breathe. Bennett’s phosphene and Icaros withdraw me from the hurried vacuum of life, an act of self-care.

Bennett’s writing arrests me, disinters the salty banks memories, transposing me to the late 1980s (I am lying on the grass at recess, staring up at light dazzled through spring’s lush foliage as my friend traces her hand along the undulating groves of a tree’s trunk, thanking it for shade). To the ensuing Women Who Run with the Wolves era that inspired our mothers’ escape to Esalen for wild women dances and shamanic healing, leaving us to our SARK workbooks. A temporal dislocation where sage lingers post-smudge, where bears and rattlesnakes portend, where butterflies are saved and named only to be surrendered to earth.

Lie on trunks of drowned forest

sharing how the heart trips and flies open.

What we leave of ourselves

for the raptors (27)

Winterson assigns to the poet the job of healing the breakdown between language and the unlanguageable. She notes that art as an ‘imaginative experience happens at a deeper level than our affirmation of our daily world’, challenging our notion of self (15). We construct our own versions of reality every day, turning to faster news cycles and social media echo chambers, becoming stuck in the mire of unquestioned feedback loops. Bennett, who believes that ‘poetry enables us to shape sounds and symbols that tie us together in the uncertainty [of] our shared existence’ cautions against trading ancient wisdom for extractive capitalism [6]:

and rivers damned

to sew the desert

in straight lines

and milk it for lattes

For the mountains

clear cut

to make toilet paper,

Masonite

and pizza coupons

For ancestors, animals,

panacea and songs…

erased (69)

Here Bennett returns us to our roots—‘in every culture a cosmic tree’ (71) — to our stellar origins — ‘Past the waves we are particle, equations of universe’ (81)—to our interconnectedness—‘if we could remember how / we’d bow our heads, trace cords / to the mothers we were cut from’ (56)—and asks, ‘How many symbols will we need / before we trust the currents?’ (87). Icaros and its predecessor phosphene are an injunction to the cycles of nature, the alchemy of ritual and the rhythms of remembering along an axis of deep time.

Notes

Brits, Baylee, and Prudence Gibson. Covert Plants: Vegetal Consciousness and Agency in an Anthropocentric World, Punctum Books, 2018.

Pollan, Michael. This is Your Mind On Plants: Opium—Caffiene—Mescaline. Allen Lane, 2021.

Brown, David Jay. Conversations on the Edge of the Apocalypse. Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Bennett, Tamryn. phosphene. Rabbit Poetry Journal as part of the Rabbit Poets Series, 2016.

Winterson, Jeanette. Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery. Vintage International, 1997.

Bennett, Tamryn. ‘Outside the Lines’. Sydney Review of Books, 10 May 2021. https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/essay/outside-the-lines/

JENNY HEDLEY is a neurodivergent writer, PhD student and Writeability mentor whose work appears in Archer, Cordite, Crawlspace, Diagram, Mascara, Overland, Rabbit, TEXT, The Suburban Review, Verity La, Westerly, and the anthologies Admissions: Voices in Mental Health and Verge. She lives on unceded Boon Wurrung land with her son. Website: jennyhedley.github.io/