Jennifer Compton reviews “The Detective’s Chair” by Anne M Carson

by Anne M. Carson

ISBN 9780645044980

Reviewed by JENNIFER COMPTON

Poetry has many pleasures, and, as quite a few of us might suspect, an almost equal share of pains. But every so often, every so often, a book comes along that panders to my desire to loll about reading a detective novel, one hand dipping into the box of chocs and riffling the paper cups to come upon an orange cream, which is my favourite. I am aware, out of the corner of my eye, of the literature outlining the comfort of a rules-based, escapist genre, where the murder victim is rarely, if ever, someone you have come to like. But it wasn’t until I read Carson’s “Reflections on writing The Detective’s Chair” at the back of this book, that I twigged that what I am really liking is the almost preternatural intuition of the crime solvers.

‘The insight came to me while I was sitting in my favourite red, upholstered chair with my legs curled beneath, a pot of Madura tea to hand: my favourite fictional detectives solve crimes similar to how I write poems. They are essentially creative people – and solving crimes is an essentially creative act.’

Then I surrendered, willy nilly, to my baser nature and riffled through the pages to check out my favourites. My orange creams. Miss Jane Marple of St Mary Mead. Who, whilst weeding her herbaceous borders, looks boldly into the dark heart of wickedness. And Detective Chief-Inspector Adam Dalgleish, of Scotland Yard, who resorts to writing poetry – your actual slim volumes – between cadavers. Although he is appropriately self-deprecating. And, of course, Inspector Kurt Wallander in Ystad, Sweden, shambling around in a welter of piles of dirty laundry and unmet obligations –

‘ … desperate for a few motionless

moments to let his thoughts run unfettered. A niggle, just out of

reach, an uneasy ache he knows holds vital clues. Something

someone said or didn’t say–elusive since the first murder. If only he

could sit quietly, listen long and open enough for it to unfurl, maybe

it would crack the case wide open.’ (p65).

Now this poem is called “Uneasy ache” but I first came upon it when it was called “The Detective’s Chair” – a singeleton, an outrider, the harbinger of plenty – and I was very much struck with the intersection of popular culture and poetry. I may have become forceful in my desire for more. I remember discussing the difficulties of tackling Commissario Guido Brunetti, because he is happy, as Anne and I took our keepcup coffees down to Carrum beach during the longeurs of Covid lockdown.

‘There is nothing noir about Guido Brunetti. Noir needs ground of

loneliness, food of melancholy. Crime-solving gets him down from

time to time but he is reflective, philosophical, dives into Herodotus

for distance. On the case, he is professional, meticulous; his nose

and native cunning winkle clues out. He doesn’t come home from

violence to empty taunting rooms, to the siren song of ghosts -’ (p11).

However, I am not meaning to imply that this is not poetry of the most serious intent and of the highest order. It understands its place within the oeuvre, it invokes tried and true devices, it succeeds as poetry. But, because it is entangled with another genre, there is a kind of slippage, and also of homage. Carson has laid down solid rules for herself, in the spirit of the genre she has playfully appropriated. Each take on a detective is a fourteen line prose poem. I suppose you could almost aver – sonnets of the prose poem ilk.

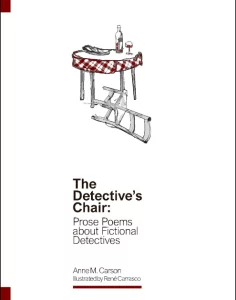

Quickly, I must mention, one of the delights of this delightful book, produced by the indefatigable Liquidamber Press, are the quirky illustrations by René Carrasco, which seem to glow with nostalgia for a simpler age. As does the dedication to Dorothy Porter for her heroic ploy to get poetry out of the bottom shelves at the back of the book shop into the display stands at the front with The Monkey’s Mask. That worked well for her, but that was 1994. However it was a bold move, and it made its mark.

‘Jill’s too busy courting trouble on the mean streets for

time in a chair, feet-up. When she grabs moments from the

malestrom, it’s her backyard fishpond which settles her. She

becomes mesmerised by the gold swirl and swish beneath, the

glimpse of a tail, hypnotic lure of dreamy movement and then the

shape of an idea emerges from the depths, leading to her next step.’ (p7).

Please do buy this book for a childhood friend or a brother-in-law or a great-aunt who isn’t quite sure they like poetry much, but who you know devours detective fiction. And then watch them forget that it is poetry they are reading, as they flick back and forth checking out whether Carson has included their particular favourites, and also to get ideas for authors new to them to chase up. And then watch them becoming absorbed and reflective as the poetry does its work.

JENNIFER COMPTON is a poet and playwright who also writes prose. She lives in Melbourne on unceded Boon Wurrung Country. Recent Work Press published her 11th book of poetry the moment, taken in 2021.