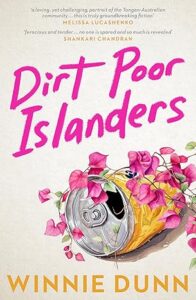

Isabel Howard reviews “Dirt Poor Islanders” by Winnie Dunn

by Winnie Dunn

Hachette

ISBN 978-0733649264

Reviewed by ISABEL HOWARD

Intercultural struggle is the main question at hand in Winnie Dunn’s Dirt Poor Islanders: how do you define yourself between two different cultures that shape every aspect of your life? Dunn’s novel is written from the perspective of Meadow, a young, mixed-race Tongan and white girl growing up in Mt Druitt in the Western suburbs of Sydney and traces her gradual assertion of who she is as she becomes a young woman. With a liberal peppering of millennial Australian and Tongan cultural references it explores themes of girl and motherhood, sexuality and poverty. But at its crux, it provides an internal viewpoint for readers to witness Meadow’s evolution from rejection of herself and all things Tongan, to understanding where she belongs between two cultures and racial identities, and within the complex map of her family.

Built around Meadow’s gradual growth and self-acceptance, the novel adopts the arc of a bildungsroman, and is split into four sections: Soil, Bark, Salt and Blood. At the start of each section, we’re greeted by a written retelling of a traditional Tongan story, such as the story of Va’epopua at the start of Soil:

The lagoon stretched further and so too did the demi-god. From coral to seaweed to salt to wave – it became clearer to him that everything emerged in pairs. Somehow, he knew that he could not be made of woman alone. So, when the demi-god’s calves became as wide as stumps, he questioned his grounded mother yet again. ‘I am made from what?’

Slowly planting taro with her stiff knuckles and gnashing inside her cheeks, Va’epopua whispered, ‘Different.’(4)

Each of these retellings foreshadows its respective section, like the parallel in this excerpt between Meadow’s mixed racial identity and Va’epopua’s son’s parentage. By using and repeating particular Tongan phrases and motifs in these retellings, Dunn alludes to a long-lived oral history and a set of values that differ from dominant Western ideas held in Australia, and she weaves connections to these retellings throughout the story as important symbols of Tongan identity, such as childbirth, soil, and Tongan foods. In fact, the whole novel is a collection of experiences laden with meanings and lessons that help Meadow make sense of her identity, emulating the nature of oral storytelling as a means of transmitting history and values.

At first, I felt that this structure meant that the story lacked a momentum I’ve come to expect from Australian fiction, in that it was missing a central conflict or mystery to drive the plot. However, as Matthew Salesses’s explains in Craft in the real world, “causation in which the protagonist’s desires move the action forward” (27) has been dictated by dominant Western ideologies of literature as the hallmark of effective fiction, leading us to undervalue traditions that have priorities other than a story’s start or end (98). Thinking about this made me realise that it was my expectation that was lacking: Dunn’s work doesn’t offer a denouement of practical solutions to Meadow’s problems because it rejects this Western storytelling vehicle in favour of a form that resembles cyclical storytelling. It emphasises understanding and interconnectedness and, basing my knowledge in Dunn’s retellings, it engages with the essence of Tongan storytelling traditions. It’s an innovative choice, and its delicate execution marks Dunn as both an original and skilled writer in the Australian landscape.

Beyond structure, Dunn centres Tongan-Australian experiences through just about every aspect of the novel. She provides nuanced representations of Tongan-Australian people, spaces, language and kinship, suffused with so much detail and feeling that her lived experience shines through, as seen in careful details like these:

My grandmother stepped out, dressed in an entirely new outfit – a shimmery puletaha with gold embroidery. Holey ta’ovala around her waist. Ta’ovala was funny like that; the poorer it looked, the richer it was, because it meant the garment had been passed down for generations. (206)

But Dunn resists one-sided glorification to represent the complexity of Tongan-Australian culture in full. She underscores the strong bonds between Tongan people and their “togetherness,” (40) but doesn’t shy away from how those bonds can become problematic, such as how Meadow’s family expects her aunt to sacrifice her intimate relationship with a woman for the sake of their traditions (163). As a woman personally living these experiences, in a country where Tongan people are plagued by negative stereotypes, I’m certain that this is a challenging step for Dunn. But by taking it with care, she’s created an earnest picture of what it means to be Tongan in Australia: the beauty and the ‘dirt’.

By being selective and sparing in how she explains Tongan culture and language, Dunn is unapologetic about prioritising a Tongan-Australian audience and making them the cultural insiders of Dirt Poor Islanders. For those who aren’t cultural insiders, this could make the novel an occasionally alienating experience – some might even argue that the lack of explanations, or the lack of provision for cultural outsiders, prevents them from identifying with Meadow and takes them out of the flow of the story. However, Dunn has made her choice clear, and I would argue that, in a publishing industry where this is the very first novel written for a Tongan-Australian audience, it adds significant value for cultural insiders that would be diminished by catering to the white gaze. Rudine Sims Bishop explained that seeing ourselves represented is a powerful and validating experience, and it’s just as important to be exposed to the experiences of others – a statement I take to mean as that, for some readers, being made to feel like an outsider by Dunn’s work is a good thing.

As someone who isn’t Tongan nor speaks Tongan, I did occasionally get thrown by Dunn’s frequent Tongan references. Upon reflection, though, I realised that this kind of partial understanding is also a common mixed race, or ‘third culture kid’, experience that I can identify with: growing up surrounded with a mix of cultures and languages, I was often in situations where I didn’t understand the words or references around me. It’s a common, isolating experience that Dunn teaches and encourages readers to empathise with by presenting it through Meadow, who partially understands everything herself.

In a similar vein, Dunn explores racial identity for mixed race and Tongan people in Australia with sensitive accuracy. Racism is the very first thing we see Meadow experience: her white neighbour yells racist abuse at Meadow’s Tongan grandmother, causing Meadow to decide to never work with her on a ngatu again (10) and sparking her association of being Tongan with dirt and muck (112). Further on, there are frequent references to Meadow or others wanting to be pālangi (50), and accusations that Meadow is not Tongan enough: ‘Me and Nettie steered clear of proper Islander girls when we met them at Sunday school in the halls of Tokaikolo. Those mohe ‘ulis demanded we spoke Tongan too, and when we failed, they mocked us. Together, Tongans were always trying to prove how real or fake each of us were. Nettie and me, we were plastic.’ (89)

With passages like this, Dunn draws attention to the ways in which we racialize people based on their cultural or linguistic knowledge and language. She shows how external messages can influence one’s racial identity and foster internalised racism, in that Meadow initially hates being Tongan, but also defines herself ‘as half and never enough, hafekasi’ (271). But to rebut the often harmful assumption that these feelings might be intrinsic or inevitable, Dunn presents us with Meadow’s rage at the injustice of racist stereotypes during class (141) and, eventually, her realisation that she can define herself differently: ‘No one could live as half of themselves. To live, I needed to embrace Brown, pālangi, noble, peasant, Tonga, Australia – Islander.’ (275)

Dunn actively rejects the ways in which Tongan and mixed-race people are stereotyped and made to feel less than their counterparts in Australia, and it’s this aspect of her writing that I’m most grateful for. Many of Meadow’s experiences and feelings are reflected in my own life as a mixed-race Filipino-Australian woman, and it’s refreshing to not just see those experiences on the page, but to see how Dunn presents them as steps in a journey of understanding oneself.

There’s plenty more to examine in Dirt Poor Islanders, such as sexuality, motherhood, and family violence. But in the interest of writing about what I know and what I believe to be the heart of Dunn’s novel, I’ve focused on her exploration of race and culture. Despite the differences between being Tongan and Filipino, reading Dunn’s work felt like slipping on a well-worn t-shirt in how empathetically she writes growing up not-quite-white in Australia. It’s a generous, powerful debut novel, narrated with a vulnerable voice, and much like Meadow’s many mother figures, it challenges its readers while fostering love and understanding.

Citations

Salesses, Matthew. Craft in the real world. Catapult, 2021.

Bishop, Rudine Sims. “Windows and Mirrors: Children’s Books and Parallel Cultures.” 14th Annual Reading Conference 1990, California State University, 5 March 1990, pp. 3-12, files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED337744.pdf#page=11.

ISABEL HOWARD(she/her) is a Filipino-Australian writer based in Lutruwita / Tasmania. Her creative work has appeared in kindling & sage, and she is currently in her Honours year studying creative writing at the University of Tasmania.