Red Dirt by Fikret Pajalic

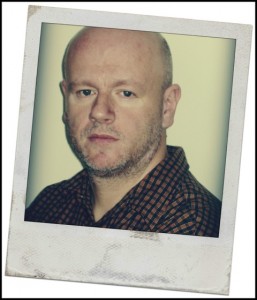

Fikret Pajalic came to Melbourne as a refugee in 1994. He has a BA Photography from RMIT and for years he used images to convey a message, only to realise that some stories are best told in words. He won equal first prize at the 2011 Ada Cambridge Short Story prize, has been highly commended in the 2011 Grace Marion VWC Emerging Writers Competition and in the 2011 Brimbank Short Story Awards. His work has been published in Platform and Hypallage magazines and Wordsmiths of Melton Anthology.

Fikret Pajalic came to Melbourne as a refugee in 1994. He has a BA Photography from RMIT and for years he used images to convey a message, only to realise that some stories are best told in words. He won equal first prize at the 2011 Ada Cambridge Short Story prize, has been highly commended in the 2011 Grace Marion VWC Emerging Writers Competition and in the 2011 Brimbank Short Story Awards. His work has been published in Platform and Hypallage magazines and Wordsmiths of Melton Anthology.

I felt the dust devil in my old bones before it formed on the paddock. The swirl of hot wind on my neck and the drop in air pressure sent a signal. Only a body like mine that spent a lifetime working the land could sense the imperceptible sign from nature.

Mack feels it too and he barks into the red dirt, taking a step back and glancing at me. I motion for him to sit and he does, uneasy and unsure. His tail hits the ground raising clouds of dust. There is something restless in the air. Something that raises the hair on both man and beast and it is best to avoid it like a dissonant tri-tone in medieval music.

‘Not of this world,’ my wife would say, urging me to stop work at noon on a hot day. She would mutter some words of protection in a language not spoken for generations. Neighbours mostly stayed away and spoke of the ‘family flaw’ that sticks to his wife’s womenfolk like a burr. Doctors talked about genetics, but I knew my wife as quirky. She spent her life trying to follow old superstitious tales only to die at childbirth while giving me twin boys.

‘May the black earth lie lightly upon her,’ said her mother after we lowered her shrouded body into the grave.

Her mother suffered from the same affliction as her daughter and possessed a myth, a legend or a tale for every occasion. She was convinced that her daughter, my wife, must have stepped over a buried body, an unmarked grave, somewhere in the field ensuring her death and marking my newborns for early demise. Now, all these years later, when my sons are long gone and their graves unknown, I think that the old woman wasn’t crazy after all.

The dust devil takes an upward shape and it moves wildly left and right across the thirsty ground. It loses momentum briefly, only to come back stronger seconds later. Mack finds new courage and rushes toward the column that stretches vertically, leaving marks on the earth like a giant pencil moved by an invisible hand. He barks and snarls and looks back at me searching for guidance. He feels that he must react, but is noticeably relieved when I call him back.

Above me the sun is sitting at noon having a short break, observing the world below, and the sky is without a cloud. It is for scenes like this that people invented the word surreal. The stillness stretched across the landscape as if someone froze the hot summer’s day. Only the dust devil danced to a soundless tune.

I put my gun back on safety and return it to its holster. The old bull will have to wait a little longer for his deliverance. I knew better than to make vila, Lady Midday, angry. Not in the old country, and not here in the red country. I kept the memory of my wife alive by following a couple of folk beliefs that she always stood by. For that reason I don’t touch the swallows’ nest that’s been in my roof for the past three years just in case they really are the guardians of good fortune.

Back in the land I was born in, it was said that Lady Midday roamed the fields during summer dressed in white. She would trouble the folk working the fields at noon causing heat strokes, aches in the neck and back, and sometimes madness for repeat offenders.

While I chew on my sandwich I watch the old bull. He is slow and cranky and he’s got cancer in one of his eyes. His hide is the colour of red cherries and his horns are grey. He is my first stud, my first buy who provided me with a steady income over the years and he helped me increase my standing with the local farmers. Not an easy thing for an outsider. He doesn’t know that he has only minutes to live.

In moments like these my thoughts always run together. I think about the old bull and his imminent death and his predicament inevitably reminds me of my two sons. They would have been forty in December had they lived. It is an irony of life that the old bull’s death will be the same as my sons.

After lunch, the dust devil is gone, dissipating in the air, but the feeling of disquiet stays with me. Mack helps me muster the old bull into the holding pen. He is a true working Kelpie and my only companion. He could run for days in the blistering heat or freezing cold. He works the cattle tirelessly by running across their backs, dropping down and expertly avoiding being stomped on. Mustering, yard work, droving, he does it all.

Mack is wise in the way of bush and stock. He trots while working and never gallops. Alert at all times and with serious expression until our work is done. He carries his tongue up against the roof of his mouth, not dangling like most dogs.

Mack and I once drove a mob of two hundred head of cattle from Dimboola to the abattoir on the edge of Geelong, losing none. We worked from dawn till dusk, my backside numb from riding and his paws hard as rock from running. His only reward was a good dinner and long pets from me.

Yet with all his apparent desire to please Mack was always able to think for himself. That’s how all Kelpies were bred, I was told. He knew how to pace himself and did not appreciate being driven too hard. There were a few occasions early on when he simply said ‘stuff you’ and walked off. But very quickly we got in tune with each other, the cattle and the land.

Those nights on the road we slept together, keeping each other warm. I would look at the stars above, pinned to the night sky in the shape of a cross, while my mind wandered to another lifetime. Tears would escape my eyes and Mack’s monotonous breathing and his warm body would send me to sleep with my heart forever full of pain.

After sleeping under the open sky we would wake with the first sliver of dawn light on our faces, damp from each other’s breath. The sun would rise in the outback reminding me of our collective smallness and my own insignificance. The greatness of the open spaces was at times overwhelming. I felt like I was drowning in the dry. After a time the land accepted me. My roots in it grew bigger, deeper. Its vastness and the work with cattle helped the pain. Days rolled into months, months into years.

More than half a century ago, when a bullock team did tillage and chemicals were found only on the apothecary table, my grandfather took me out to our fields for my first lesson about the land. It is a peculiarity of my mother tongue that we use one word for both the land and the Earth. Hence, all the lessons I was given, and they were only a few as my grandfather departed shortly after due to a weak heart, were the lessons about the Earth itself. And every life lesson is only a chapter in the book of death.

We knelt together on the ground and both grabbed a lump of black soil. Moist and clumpy, it stuck between my fingers. I cupped my hands and clapped them together. The sound coming from them was soggy and succulent. I put my dirty palms to my nostrils and smelled the soil. ‘Earth like this’, my grandfather said, ‘will give you all she’s got,’ and he beamed with joy. Somewhere in that same black earth, the remains of my sons are buried.

After arriving in this pancake flat part of Victoria my compatriots, refugees like me, and locals from Dimboola shook their heads in disbelief. Both sides said that ‘the country life is not for a foreigner.’ I had doubts too but kept them to myself. I had my own pain to carry and had nothing left of me for others.

Thankfully, my neighbour, an old man with thick white hair, but still straight as a pine tree, who lived on the station next to me didn’t agree with them. A day after my arrival he stopped by to introduce himself, bringing two legs of lamb and two kilos of steak.

He expressed his amazement that someone bought the land and told me that the first thing after getting a ute I needed to get a dog. He spat on the red earth and said that he would make a true-blue Aussie farmer out of me before the spit dried. ‘Or my name is not Pop McCord,’ he radiated with sincerity.

‘You only have two breeds to consider out here,’ he continued nodding at the vast expanse in front of us. ‘It’s either Heeler or Kelpie. Them little buggers are worth ten men easy. And they’re smarter than them too. Mark my words.’

I could not decide and told him that both looked very cute. I was about to elaborate on that and tell him that Heelers look like canine pirates with those dark patches around the eyes. Lucky for me Pop interrupted.

‘Cuteness got nothing to do with it, mate. Out here,’ he pointed with his thumb over his shoulder, ‘dogs aren’t pets. They’re workers. I reckon,’ Pop rubbed his stubble, ‘since I got a Kelpie bitch you get yourself a healthy Kelpie pup and next summer you and I will have some puppies to take care of.’

I nodded in agreement and Pop put an arm around me like we’d been friends forever and said ‘fan-fucken-tastic, I’ll pick you up at six sharp.’

The next morning we were on our way to Casterton where I picked Mack, a black-and-tan pure working Kelpie from a breeder for $900. At the time I thought that to be an outrageous price to pay for a dog only for Mack to prove himself later as invaluable. Just like Pop proved to be the best teacher a newbie in the outback could wish for. Everything I needed to learn about my new country I learnt from Pop and Mack.

As I walk toward the bull I see a cloud of dust billowing in the distance. Briefly I think it is another dust devil and later I wish that it were. Soon I recognize a motorbike heading in my direction. The feeling of disquiet returns and overwhelms my whole body like a tsunami hitting the shore. The postman is a new bloke, young and with skin complexion too fair for this part of the world. He looks like he’s been carved out of giant block of feta cheese and sprinkled with ground paprika.

‘G’Day Mr. Shmmm…,’ and he stops unable to pronounce my surname. I wave at him indicating that he should stop twisting his tongue. Years ago Pop would get annoyed with people who got my name wrong. That was until I told him that ‘they can call me a jam jar, for all I care, as long as they don’t break me.’ The young postie handed me a slip to sign.

Moments later I was holding a registered letter from International War Crimes Tribunal postmarked from Hague, Holland. It has been many years in coming. I walk over to the sparse shade of the mallee bush and open the letter. After I read it I fold it in half and put it in my shirt pocket.

I climb up the metal bars of the holding pen and sit above the old bull. We look at each other briefly. His brown eyes betray the last traces of hope. He starts thrashing, his eyes rolling in panic. He senses the end. If this old bull knows that there are only seconds left to live then my boys must have known too. I see their faces in the crowd of beaten men. Their scared eyes are searching for me.

As I point the gun between the horns, the crisp paper of the letter is rustling in my pocket. The envelope is whispering to me, telling me again everything I just read. It was a letter I was hoping never to receive but knew that it was coming. I was like a child who heard a bedtime story about the big bad wolf and then met one for real.

The monsters could not look them in the face. They shot them at the back of the head. Their hands were tied with wire and they were taken to the forest in pairs. Did any of three hundred and twelve men try to run? Did they cry, plead for help? Or did they collectively resign themselves to their fate? I imagine that hopelessness spread like wildfire among the condemned men. It is said that is common when collective fear grips people and paralyses them.

Which one of my boys fell to the ground first, while the other listened to the bullet bursting through the head, cracking the base of the skull, exiting on the other side and smashing the facial bones to pieces.

My finger is frozen on the trigger. In my mind I see the bullet leave the chamber and travel through the barrel. It enters the bull’s brain and continues down his spine rendering him dead in one precise hit.

The bull falls sideways and his heavy body hits the dirt raising red dust. There is a moment when I almost expect the bull to stand up and say to me defiantly ‘one bullet is not enough for me mate’. But it’s never happened. I have done this many times and my hand, despite my age, was always steady and my eyes sharp. There is a skill to killing an animal this way. And every skill is just a matter of number of repetitions.

Afterward the thud and the gunshot reverberate through my body and the whiff of gunpowder streams through my nostrils hitting the most hidden chambers in my brain, momentarily putting me on a high.

Mack would always look away during these moments. When I am done he would give me one of those stares with which he asks me if the same fate awaits him when he becomes old and decrepit and not able to run. Later I’d whisper to his big ears that we all are going to end some day.

This time Mack does not take his eyes away from me. He is surprised as I am. There is no shot, no gunpowder and no thud of 700-kilo bull. I climb down and let the bull out of the pen and he runs with a furious step, nostrils snorting.

Pop told me that he used to cut the carcasses of his dead cattle into fist size chunks and inject the meat with poison 1080. The meat would be scattered around the edge of the paddock in a five-kilometre radius.

‘We believed it to be the only way to protect the stock from packs of roaming wild dogs that tear the faces off calves before they eat them.’

He said that he stopped doing that when he saw a poisoned dog contorting in agony. While he talked about the damage this poison does to other animals I switched off and wondered if there is poison number 1079 and 1081. How many poisons did we create to subjugate nature?

‘It takes those wild bastards a whole day and night to die.’ Pop interrupted my thinking, shaking his head and not looking me into eyes. We both now have electric fencing and Pop keeps saying that we ought to get some livestock guardian dogs.

‘Bastard or not, no one deserves to die like that.’ Pop concluded.

But Pop was wrong. There are demons in the shape of men out there that deserve to die a death just like that and a thousand times worse. On their knees twitching in a cold sweat while poison tears through their insides, frothing at their mouths and bleeding from their eyes for days.

Pop’s ute is an old Holden with a bench seat and column shift. We’ve been travelling for a couple of hours and the landscape to Melbourne is gradually changing from red to green. I look back at the sweep of blue gums that we are leaving behind us and like an orphan child I find myself missing the mother who adopted me.

Mack is sitting in the middle with his head on my lap. He knows something is up and he’s been quietly whining since we started the trip.

‘You’ll be all right with me for couple of weeks Mack, won’t you mate?’ Pop asks him to reassure both Mack and me. He then changes the subject and tells me about the bull.

‘The vet said that the eye operation went well. He reckons he removed all the cancer from the eye. Evidently the bull’s crankiness went out together with cancer.’

I manage to open my mouth and thank Pop.

At the airport I kneel down and talk softly to Mack. I can hear the spongy blinking of his eyes through the commotion of travellers.

Before we say goodbye Pop hands me a jar full of red dirt. I look at him, unsure.

‘So your boys always have a piece of you with them.’ He says and hugs me. As we embrace, Mack protrudes his muzzle between us and lets out a soft bark.

#