Deborah Pike reviews The Great Undoing by Sharlene Allsopp

by Sharlene Allsopp

ISBN: 9781761151668

Reviewed by DEBORAH PIKE

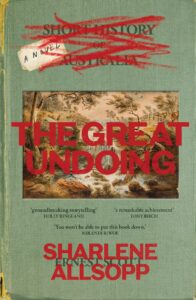

Sharlene Allsopp’s debut novel, The Great Undoing, has a great cover that undoes history with a red crayon. Ernest Scott’s A Short History of Australia (1916) is struck out and bold typeface declares an angry and urgent call for a different version to be told. As Allsopp writes, ‘After all, only the winners write history.’ The ‘story stealers’ (1) have already written theirs, clearly, the time is ripe for a re-write.

I looked up Scott’s book, with some curiosity, to find virtually no information except advertising from antique bookshops via eBay. And now I am assailed by emails and popups, recommending Scott’s volume for purchase. But how long can these versions of history last, I wonder?

As more and more First Nations writers confront questions of representation, voice, colonisation and sovereignty, previous stories and histories of Australia will need to be thrown into question. History, it seems, is being rewritten by First Nations authors like Sharlene Allsopp, Claire G Coleman, and Alexis Wright – via fiction. Fiction has become the space for dismantling empire and for writing and rewriting history into an imaginary place or into a speculative future.

The Great Undoing is set some time, decades ahead, where the world is run by a technology called BloodTalk. Allsopp writes, ‘Everything that we are is stored in our body’ (17). Initially an immunity tool, it is soon used to track people and their locations as well as their bank accounts; it becomes a form of border control.

But the future is not all bleak, certain things are being rectified: Australia has its first Indigenous Prime Minister, ‘Ruby Walker’ who ‘enacts the Truth Telling Policies’ (34). Scarlet, an Australian refugee is tasked with the job of updating the archives and going through curricula to make sure that these are more historically balanced and that more voices are heard, presumably in a way that includes and details Indigenous stories, names and languages.

The novel flashes back and forth from Then to Now. While Scarlett is working in London, she forms a passionate relationship with a rock musician, Dylan. But there is a widespread mass blackout and a breakdown in communications. Everything is in chaos and borders are shut. Scarlet then meets David and they both travel, seemingly illicitly, across the globe to return to Australia, each for a different reason. Scarlet resorts to paper and pen to recount her experience of her ‘great undoing.’ All she has to write on is a copy of Scott’s A History.

But what is Scarlet undone by? Is it the great global technological disaster itself? Or Empire that stripped her of her story? Or is she ‘undoing’ Empire through her truth-telling work? She writes, ‘My father’ – a Bundjalung man – ’was my great undoing’ (25). Is his racial identity the source of her undoing? Or, later, we might ask, is she ‘being undone,’ in a steamy way – as she narrates her romantic encounters with poetic, scintillating prose: ‘[h]e was undoing. I was undoing. And, right then, right now’(67)?

Allsopp suggests that Scarlet’s undoing lies in all of these things, but ultimately, however, it is the undoing of identity, the pursuit of it, that sweeps the story along; the book is a meditation on both the complexity of identity and the nature of textuality – and their interwoven relationship.

In parts, the novel reads like a response to Wiradjuri author, Stan Grant’s brilliant, (if somewhat controversial) essay On Identity (2019). In his book-length essay, Grant argues against the limiting categories of identity – ‘Identity does not liberate, it binds,’(43) explaining that ‘[t]hat’s the problem with identity boxes: they are not big enough to hold love’ (19). He Writes:

If I mark yes on that identity box, then that is who I am; definitively, there is no ambiguity. I will have made a choice that colour, race, culture, whatever these things are… (25)

The result is that by ticking that box, he denies the other parts of his identity which do not fit into that box, ‘we participate in an infinity of worlds’(24), says Grant, citing Alberto Melucci, which such boxes cannot possibly contain. In a similar vein, Allsopp writes:

There have always been tiny, neat boxes to tick. Nationality Box, ethnicity box, gender box, religion box. If you tick or cross you are contained within that box. (195)

Grant attributes his influences to many writers of all colours and persuasions, insisting that many writers are Aboriginal (48), even if their genetic code would tell you otherwise, because (quoting Edouard Glissant),‘“you can be yourself and the other”’ (43) and this is what literature allows us to do. . Allsopp is also interested in showing her indebtedness, her connectedness, to a wide range of writers such as David Malouf, Rebecca Giggs, Claire G Coleman, Christos Tsiolkas and, even J. R. R. Tolkien, among others, all of whom she refers to in her book and occasionally quotes.

Arguably, however, in its attempt to reclaim Indigenous language, storytelling and identity, Allsopp’s main literary influence is that of Tara June Which and her novel The Yield, which Allsopp explicitly mentions. This is because, for Allsopp, as for Winch, language is crucial:

Language isn’t just a tool to share information or to record history. Expressed thought is powerful. It declares truths that are, and truths that are not-yet. Language breathes power into discourses of liberation AND oppression, both creating and destroying futures. (105)

Since language shapes our perception of truth, or ‘frames’ it as Scarlet tells us, it is directly linked to history, and to her job of setting it right. This is a challenge when so many Indigenous languages have been lost. In an insightful (and amusing) discussion of the power of language, Scarlet warns us that much language is used and has been used mistakenly, to wield forms of control, however unconsciously in so many ways: ‘Our language frames us all with penis-envy,’ but when considering its marvellous capacities, ‘It should be vagina-envy, baby.’

Truth telling is also central to the novel’s concerns. But this is not straightforward, ‘When a nation is built on a lie, how can any version of its history be true?’ (119). Allsopp is deeply interested in how truth can be conveyed through narrative, even hinting that there lies the possibility for multiple and perhaps even conflicting ‘truths.’

The Great Undoing examines the ways that narrative structures our perception of both cultural artifacts and the world around us. It exposes the rotten imperial core of major museums and institutions, and gloriously imagines, however briefly, how all this might be remedied. The novel is interspersed with historical tracts and extracts; it is highly experimental fiction, and robustly formally inventive. It is in some ways a narratological compendium, exploring different forms of textuality – in a bid, perhaps, to showcase the breathtaking heterogeneity of various versions of ‘truth’ and history.

In terms of style, the writing is refreshing, bracing and often affecting. Allsopp combines high literary elements with aspects thriller and romance. This genre-bending attests to the possibilities of narrative – and to the difficulty of containing or accommodating certain stories and fractured histories. It could have been the limitations of this reviewer, but at times, I found The Great Undoing difficult to follow.

Despite this reservation, The Great Undoing is exciting reading and it is a pleasure to encounter fiction that is so ambitious, conceptually intellectual, and yet at the same time, also thoroughly immersive. This is an important book.

The novel’s sense of urgency is compelling:

But what if no one tells our stories? What if there are no records left? Can they live on if they only exist in our memories? What if everything I have ever done, every truth I have ever retold, is erased? (169)

Allsopp wants to right the wrongs of the past, reclaim memory, unravel the mystery of identity, throw a tin of paint on the face of history, nudge to possibility – convey the complexity of all these things – as well as give us a rollicking good adventure. Who can ask for more?

Citations

S. Allsopp. The Great Undoing. Sydney: Ultimo Press, 2024.

S. Grant. On Identity. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2019.

DEBORAH PIKE is a writer and academic based in Sydney and an associate professor of English Literature at the University of Notre Dame, Sydney. Her books include The Subversive Art of Zelda Fitzgerald, which was shortlisted for the AUHE award in literary criticism. The Players, her debut novel is now out with Fremantle Press.