Carielyn Tunion-Lam

Carielyn Tunion-Lam (she/they) is a writer, videopoet, educator, and cultural worker. She has worked in the arts & cultural sector, the community services sector, and has experience using creative strategies in grassroots community organising.

Carielyn Tunion-Lam (she/they) is a writer, videopoet, educator, and cultural worker. She has worked in the arts & cultural sector, the community services sector, and has experience using creative strategies in grassroots community organising.

Carielyn is interested in exploring themes of radical softness and nostalgia, and the tropical Gothic from an anti-colonial, diasporic perspective. She is a participating artist in Curious360 by CuriousWorks, and her work has been published by kindling & sage, Mascara Literary Review, Emerging Writers Festival, SBS Filipino and KAP Magazine. She is currently studying a Master’s in Literature & Creative Writing at WSU. Carielyn’s ancestral roots are in the archipelago of the so-called Philippines, and Kowloon, Hong Kong. She currently lives, studies, works and treads respectfully on unceded Burramattagal on Dharug country.

I am a deep-sea fisherwoman, but I do not catch fish

“…the diasporic woman’s identity is always already fractured and for her[,] autobiographical writing and the process of subject formation lies in celebrating the fracture rather than attempting to cure it.” – Bidisha Banerjee, 2022.

I went handline fishing once and was useless at it. I ended up seasick, huddled and damp in the stern the whole ride back to shore. Years later I would rent a cheaply converted garage in Umina, my answer to a yearning to be near the sea. I would swear up and down Ocean Beach Drive that I’d learn how to fish, hellbent on the idea that if I eat it, I should be able to hunt it or harvest it. But to this day, I’ve never caught a single fish.

Dr Leny Strobel says that Filipinos are consigned to fishing – not just because our skin is home to the salt of our islands – but because we’re fated to gather stories turned adrift. To those of us for whom fragmentation is genesis and legacy, fishing for stories is a way of coming full circle. A way of mapping the fractures and fissures that make up the ever-shifting landscape of our histories, our selves.

So okay, I may be shit at fishing but perhaps I am a fisherwoman after all.

*

Separation

I float a wave back to the Parañaque house. A bougie two-storey townhouse with stucco walls packed tight with dreams. Bordered by coastland in one of Metro Manila’s earliest gated villages, the estate was bankrolled by the Banco Filipino empire before its forced closure under the first Marcos dictatorship. Papa’s modest self-made fortune had just reached its peak when he bought the plot, and it would be another decade or so before finances would start to dip. He grew up struggling, and mama’s family still were, so maybe this house was their way of buying into a vision of security and success. I remember it being huge in the way everything is when you’re a kid. Crossing the Pacific again some twenty years later, I’d come back to an anachronism. How much smaller it would seem.

My parents built the house in the early-1990s, drunk on the siren song of domestic bliss. My father used sand and bare hands. My mother opted for perennial plants. I imagine them playing house in some high-stakes game of pretend: man, not-wife, and the new baby. In a few years, they could enrol the child to an international school nearby. The woman could start a small business selling locally-made Narra-wood furniture to rich households. The man might even leave his wife. They’d be a real family. When you wish upon brick and mortar against the Amihan tides.

Over the years, the waters would rise. Trade winds would blow their relentless cycles but the house would stay the same. An empty, yearning nest. It would miss out on first words and first steps, stay oblivious to fists and fights, the paranoia and bald-faced lies. Its walls would never feel the touch of warm hands and its windows would never open for sunlight darting through its rooms. Termites and mice would lay claim to the bones. A salty damp would set into the floorboards. Its foundations would crack and loosen underfoot, an ocean between us, always.

The neighbours would set their sights on it. They’d pick its locks and enter by stealth. Maybe they sought to lick the gilt off the cornices, scrape the good intentions off the walls. Maybe they took the door off its hinges to see if anything worthy lay on the other side of the frame. Ethically, I don’t oppose the break ins. Why should a house stand empty in a city where sleeping bodies line the streets?

Twenty years would pass and I’d scrap for a plane ticket back. I’d smash the padlock off the gate, jarring in its errant coat of red applied by some interloping budding decorator.

I’d stand in the wreck of it and let the smell of forgetting fill my pores. I’ve scrubbed my body many times since, but I carry it with me still, to this day.

*

I hesitate to identify as Filipino. The word derives from the Spanish coloniser king Philip who, through Magellan’s colonial activities, staked false claim over the archipelago’s diverse peoples, lands, skies and waterways. To frame myself as a little Philipp-ite is reprehensible to me yet I use this label as a way of speaking the language of the dominant tongue, to use its tools of categorisation as a way of carving out space. It is a way of having voice, misconstrued though it may be – a way of insisting, I am here! My people have dived for pearls with friends here, well before your white sails bruised these shores.

The poet Eunice Andrada has been known to identify as an Ilonggo poet, resisting the homogenous ‘Filipino’ label which reeks of Tagalog hegemony in the archipelago. The issue of identification and identity is further complicated for me by lost family and ancestral histories. It was only on my 33rd birthday last year I learned my maternal grandmother was from Pangasinan, land of a thousand islands. I have no stories, no photographs of her as a child to go by, but this is how I like to picture her. A girl growing up by the sea.

*

“Non-fatal drowning describes a drowning incident where the individual survives. In some cases, an individual may not suffer any serious health complications following a non-fatal drowning. However, in other cases, non-fatal drowning can significantly impact an individual’s long-term health outcomes and quality of life.” – Royal Life Saving Australia

The first time I remember drowning:

Ma and I had just moved into a rental in Dee Why, which kids at my new school called ‘the ghetto’ of the Northern Beaches. I remember thinking, if this is ghetto, you’d die to see where my family live. I’d soon realise they called it ‘the ghetto’ because it was the only ‘ethnic enclave’ on the insular Peninsula(r). The only suburb in the area with an Asian grocer and an African beauty supply store, where the Pinoy and Pasifika families lived, where the Chinese restaurants were legit. I’d never lived in the suburbs before. All I’d known was city smog and chaotic traffic, so I fell quick and hard for the nearby beach.

I went walking on the shore in my school dress one day, brogues and socks on my hands, toes questing in the sand. Suddenly, the sky rumbled grey and the tide began to surge. Water climbed my legs fast and snatched me up into the churn. My mouth filled with saltwater. I started to swallow. I remember thinking, goodbye, mama – strangely calm about it all. That’s when I felt a warm hand close firmly over mine, guiding me out of the crush. My head burst above water, kaleidoscopes of seafoam and upside-down pine trees in my eyes. I lay on the wet sand, strewn under a glassy sky. Soaked to the bone and completely alone.

I don’t remember much else, everything is a vague before and after that moment. My memory has always been hazy. Twenty years later, I’d remember that drowning and wonder, was it a memory, a vision, a dream? I still can’t decide. Whatever happened, I know it was my lola who saved me.

*

When I tell my mother this, she gasps.

Da, the same thing happened to me!

A monsoon season sometime in the 60s drowned the Pasig River leaving it bloated and swollen. She went swimming in the floodwater, seeking pearls amidst candy wrappers and bits of corrugated iron, floating wreckages of plastic debris. Maybe the current got stronger, maybe her little arms got tired and she started to sink. But Naynay reached into the river and pulled her out in a strong, calloused grip.

How funny, ha, Da. She saved me but she was so angry with me.

That night I dreamt of mama as a girl, eating clams with her mother. They fished them out of the water, scooping them up in their hands by the riverside, heads bowed like grateful penitents.

*

Transition

People tell me I look Japanese. They say, but you don’t look Filipino, which is funny because the archipelago comprises nearly 200 ethnolinguistic groups with distinct cultures, stories, Peoples, and rituals. Not to mention the myriad cross-cultural ancestries from beyond the oceans before the intrusion of colonisers and conquistadors. People rarely clock me as Hong Kongese, except my Filipino family who laugh themselves stupid over jokes about my eyes looking ‘inchik’. Truth is, I don’t know if I should identify as Chinese either. My father calls himself a Chinese man but identifies more as a Hong Kong man.

Can I just identify as an island gal? An island baby they-by lady?

*

I started the process of forgiving my father around ten years ago. We drove around Kowloon listening to ‘Don’t cry, Joni’ and ‘La Vie en Rose’ on repeat while he dredged up memories of Japan’s occupation of Hong Kong in WWII like pulling dead fish from the sea. He told me of bodies piled high on streets now stacked with concrete pylons and apartment towers, the same streets beneath our feet. During martial law, people hid in their homes as often as they could. But my father, only seven at the time, tired of fear and the hunger in his belly, would sneak out to shine imperial soldiers’ boots in exchange for biscuits which he’d save to eat with his siblings.

My lola would have endured the Japanese occupation of the Philippines but when I ask my mother about this, she tells me she has no idea what I’m talking about.

My island homes sink and swim with the weight of remembering and forgetting.

*

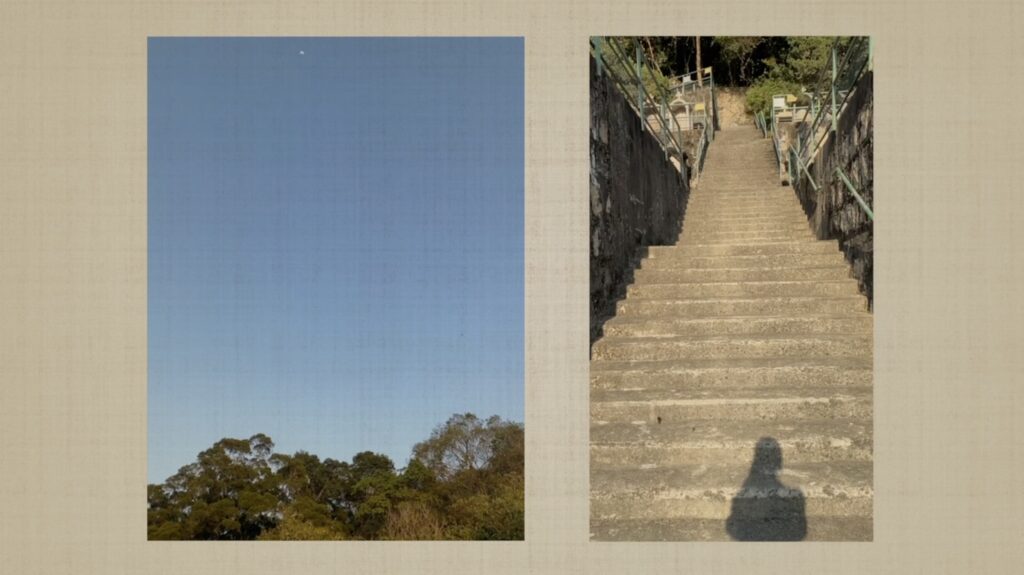

I met Papa as an old man this year. To be fair, with sixty years between us, he’s been old my whole life. Mortality on our minds, he took me to visit his parents’ graves for the very first time. I balked at the interminable staircases at St Raphael’s cemetery where his father, my 爺爺 rests. Irene was there, his girlfriend of 30 years who’s also 30 years his junior (I met her, too, for this first time this year). She held him as he gripped the flaking green rail, one step after the other. I was scared he’d fall or faint, but he refused a single word of complaint, out of reverence or stubbornness, I’m not sure. Oliver and I sentried in front and behind. A black butterfly trailed us. Hobbling back down, we made the shape of some lopsided creature of grief.

His mother, my 嫲嫲, lay in Wo Hop Shek some 40 minutes away, in a Buddhist graveyard on the hills overlooking Fanling. I was inept at bai-san but I lit the incense, bowed my head thrice and burned the bag of paper prayers adorned with Kwun Yum riding the sea, lotus flowers at her feet. I held Papa’s hand as ash and smoke unfurled in the blue silk sky.

The next day, he confessed with tears in his eyes that his sons don’t visit his parents’ graves. We were in the backseat, ‘La Vie en Rose’ playing again. His unspoken fear that they will not visit him either sat between us.

*

When Lam Him died, he left behind five adult children as his legacy. One was my father, Lam Shuk Chiu, who, devasted by his father’s death, tried to give his heartache purpose by honouring his Honourable Father’s death, honourably. He threw himself into funerary arrangements, buying the finest oranges, chickens, and pigs heads for offerings; and bargaining (respectfully) with a nun to guarantee his father’s dying wish for a Catholic burial after a lifetime as a sometimes-practicing Buddhist – a testament to the care he received at the Catholic hospice where he’d stayed.

After an evening meal, the grieving family sat together on mats on the floor to share memories of their devoted patriarch. As they did, the lanterns began to flicker and the dogs out on the terrace barked feverishly into the night. My father felt the room go cool. A light pressure touched his forehead, and he lost consciousness. When he came to, a sense of peace washed over him.

That’s when I knew, he tells me.

There is no such thing as ghosts. Only spirits.

Incorporation

Is there another me in a same-but-different version of Hong Kong? I imagine her also 33, speaking Cantonese since she was a baby. She visits her ancestors’ graves often, knows the right joss sticks to buy, doesn’t get anxious about her choice in flowers for offerings.

Is there a version of me in the so-called Philippines? She probably doesn’t bother with inane questions like this.

*

My mother has a lot of stories she doesn’t know how to tell. She buried them in forgotten soil and lost the words to unearth them again.

She’ll rewrite herself again.

My father’s stories always lied just behind his tongue. Now he’s opening up, telling me ghostsongs and lovestories around his old fishing town.

Me? I am a deep-sea fisherwoman, but I do not catch fish.

Videopoem (still): ‘lullaby for a fisherwoman’, 2023

Cited

Banerjee, B. “Alphabets of Flesh”: Writing the Body and Diasporic Women’s Autobiography in Meena Alexander’s Fault Lines, English Studies, Vol. 103:8, 1210-1227, 2022. DOI: 10.1080/0013838X.2022.2105025

Del Rey, L. ‘Grandfather please stand on the shoulders of my father while he’s deep-sea fishing’, Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Boulevard, Polydor, Interscope Records, 2023.

Strobel, L. Coming Full Circle: The Process of Decolonization Among Post-1965 Filipino Americans, 2nd ed. The Centre for Babaylan Studies, 2015

Tan, C. ‘Interview #125 – Eunice Andrada’. Liminal Mag, 2020. https://www.liminalmag.com/interviews/eunice-andrada