A.J. Carruthers reviews Experimental Chinese Literature by Tong King Lee

Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics

by Tong King Lee

ISBN: 978-90-04-29338-0

Reviewed by A.J. CARRUTHERS

Debates have been raging, in avant-garde studies, over the terms that we might deploy to describe such cultural productions and the longevity of such terms. How do we name unusual literatures in the near present? “Avant-garde” or “neo-avant-garde,” or “avant-garde” and the “contemporary experimental”? Does the historical specificity of the vanguard then preclude usages outside of this, and if so, does “experimental” then sound better historically; the history of experimental literature then to be figured as including many historical moments and contexts rather than stemming from one, what sometimes, and irritatingly gets called the “historic avant-gardes” (as if any other vanguard was not also historic)?

In Brian Reed’s Nobody’s Business: Twenty-First Century Avant-Garde Poetics (2013) we were alerted to the possibility of extending the half-life of the term “avant-garde” in poetics. It brings up enough questions to thoroughly occupy any scholar or layperson starting out in the area, as the Preface states:

Since the 1960s, avant-gardism has a mixed, complex history as a critical concept. Can an authentic avant-garde still exist? Or can there only be shallow effete echoes of past movements and achievements? Can an avant-garde ever actually succeed in bringing about revolutionary social transformation? Does an espousal of vanguardist aims amount to enslaving art to the logic of the marketplace, especially the constant demand for new products and new fashions? Is avant-gardism inherently masculinist? Is it solely a Western phenomenon? The bibliography on such subjects is immense, beginning with Renato Poggioli’s Teoria dell’arte d’avanguardia (1962) and including such landmarks as Peter Bürger’s Theorie der Avantgarde (1974), Andreas Huyssen’s After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism (1986), and Fredric Jameson’s Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991). One does not have to delve into the footnotes, however, to know that shock and resistance generally characterize the literary establishment’s response to an avant-garde’s emergence. (“Preface” xiii)

I am not interested in further wrangling over terms here, and the various ways that one can navigate this critical history, so much as getting to the works and to the poetics of this book; from this we might see how some of these questions, themselves, might be expanded upon or modified in new light. For that, Tong King Lee in Experimental Chinese Literature: Translation, Technology, Poetics, published in Brill’s Sinica Leidensia series, going since 1931, is an excellent contribution to the field. The argument begins suitably skeptically: “Indeed, it is something of a paradox to speak of defining experimental literature, given that definitions are by their nature institutionalised, and hence to some extent, this runs counter to the spirit of experimentalism” (1).

Two broad elements in Lee’s argument are the materiality of the signifier and technology. How it plays out though will be culturally specific. The roots of these blooms of invention come from the Chinese language which “is often said to be highly visual thanks to the pictographic roots of many of its radicals and characters. On the aspect of sound, innovative poets are able to exploit numerous homophones in Chinese as well as onomatopoeia to create sonic effects that play out the malleable space between signifier and signified” (4). Significant here is that these sonic effects “play out” rather than “play out in” in the malleable space between signifier and signified. There is no sense of an in here, no internal space but rather some outfacing exteriors.

The case studies deal with literature and literary language but also intersect heavily with art practice, and the various ways that art practices have taken up the “semiotic operations” found in other experimental works and across modes (131). Chapter 2 focuses on Machine Translation in Hsia Yü, Chapter 3 on Chen Li, and Chapter 4 on Xu Bing, the well-known conceptual artist. The chapter on Hsia Yü builds off deconstruction, flirting with the notion of the Death of the Translator, an interruptive différance and authorial disavowal to get to HsiaYü’s Pink Noise, a literally transparent book, made of see-through polyurethane leaves, and the intriguing notion of “lettristic noise” (wenzi zaoyin 文字噪音). The emphasis here is on unoriginality, uses of dismantling and permutative means through the digital, and sampling methods. Pink Noise uses Sherlock translation software, and the use of a machine translator “fulfills the poet’s aesthetic expectations of producing irregular poetry by way of its blatantly literal, often unintelligible, and always non-fluent translations” which is to say further that in some bid “to defy the etymological notion of transference in translating (‘translate’ in modern English comes from Latin translatio, ‘carrying over’), the poet textualises the impossibility of ‘carrying across’ any determinate meaning from some perceived source text to some perceived target text by exploiting the openness of language though MT” (34). Google-Translate then allows for back-translation, and a certain degree of grammatical torque and distortion. Lee stresses the embodied and the monstrous here too: Hsia Yü’s use of machine translation intimate with a markedly corporeal poetics. I imagined another comparison with Pink Noise along these lines would be the works of Idris Khan.

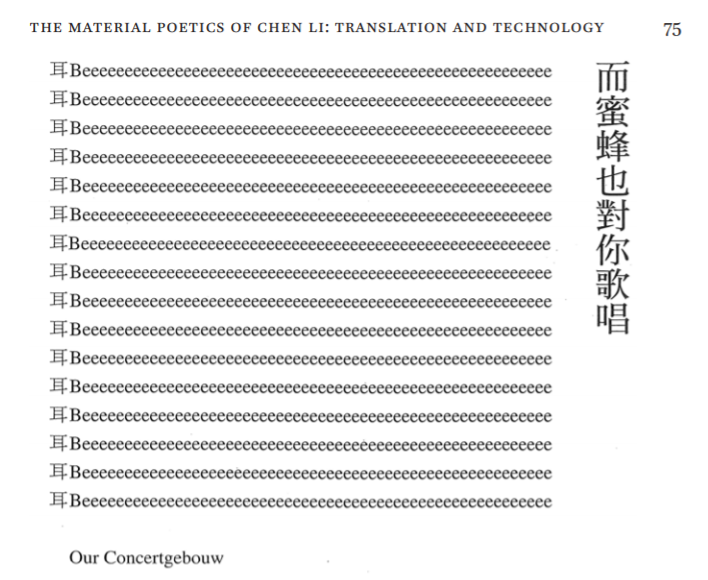

Examining Chen Li’s various works both online and in print, Lee then brings the material elements more closely into focus, putting text to theory around technology and the digital. Chen Li’s poetry embraces concrete poetry, or tuxiang shi 圖像詩 (‘picture-image poetry’), and “visual play on the architectonics of the Chinese character,” elements that fit well with the language: “The pictographic quality of the Chinese script makes it especially amenable to such manipulation” (70). The semiotics of this is compounded and exploded when it comes into the context of bi,- and tri-lingual innovation. Lee offers a reading for the visualist piece “Our Concertgebouw”

Lee brings the materiality of the Chinese signifier in Chen Li precisely to the “technologisation of the word” in way that, in other works like “A War Symphony” show translation to be part of the process of writing itself, not just living in the temporal afterlife of an original. In Lee’s reading of Xu Bing’s language-art works, the complementary Tian-shu 天書 (A Book from the Sky) and Di-shu 地書 (A Book from the Ground), the latter published in an edition from MIT Press, and which is comprised of color-printed emojis that complete a fairly straightforward narrative of one man’s day (somewhat a modernist troping) which I originally read as a novel. As Lee points out, Xu Bing’s purpose is to get beyond the notion of English as a universal language; it is, so to speak, a pre-Babelian vision, one that both harks back to Egyptian hieroglyphs and Sumerian cuneiform and the fate of the written word in digital communication. That is to say, the sheer interactivity that goes on in translation and between modes and text-types is more than a metaphor for intra, or transculturality; these Books seem like, with a dash of art-conceptual irony, real attempts to break through and take a shot at getting beyond translation altogether.

As is of utmost importance to the literary critic, Lee succeeds in bringing the clarity of terms to the specificity of texts. Lee is smart with terms and engages subtle argumentation, outlining the underlying differences between intracultural (within cultural spheres) and transcultural (across or between cultural spheres), and he aptly uses the term intersemioticity which allows us to regard non-verbal signs as “semiotic entities in their own right” (7). I think the term intersemioticity is very wise indeed, when taken back into a properly literary-critical context. Intersemioticity implies also that the seminating influence effects modes and modality. Intersemioticity is especially useful in making sense of Chen Li’s poetics; alongside interlinguality and intermediality. Multimodality is useful in discussing machine translation in Hsia Yü, and we see too in his readings of Xu Bing the value of W.J.T. Mitchell’s work — the imagetext — in normalising and expanding upon the techniques of visual reading, attention to pictoriality and the iconocity of literature.

If it is true that most sizeable literary cultures (or national literatures) have their experimental front lines; inventors, innovators, avant-gardes or neo-avant-gardes, call them what you may, it is also true that not every one of these has a critical industry built around analysing the experimental texts that they produce. Happily, the scholarship and more specifically, literary criticism dedicated to identifying the tendencies of specific avant-gardes and decoding or reading poems outside European and North American contexts, is growing steadily. Over the past ten to fifteen years, comparative studies have shed light on neo-avant-garde practices in transnational, transcultural / intracultural, regional and hemispheric contexts, shifting to explorations of the diasporic avant-gardes and studies of too- much-neglected figures who circulated among the early twentieth-century avant-garde, like Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. One might speculate how the seeming “exhaustion” of current European and American experimental poetics might be reawakened through these interlingual contexts.

Given the context in which this review appears, it is worth adding that developing work on Australian experimental writing might also contribute to this scholarship, widening the reach and regional applicability of such concepts. It is curious that Australian criticism has struggled to find ways of fruitfully speaking about inventive writing, and that no full book has yet been produced on Australian experimental poetics.

I read Experimental Chinese Literature with pleasure and with hope that its sharp critical observations can be of broad use to the contemporaneous flourishing of avant-garde studies, and bring new questions to the field.

A.J. CARRUTHERS is an Australian-born experimental poet, literary critic and lecturer in the Australian Studies Centre at SUIBE in Shanghai. He is author of Stave Sightings: Notational Experiments in North American Long Poems, 1961-2011 (Palgrave 2017), a book of literary criticism that examines five North American long poems and their relation to musical structures and musical scores. The first volume of his epic poem, AXIS Book 1: Areal, was published in 2014 (Vagabond). Opus 16 on Tehching Hsieh is a downloadable eBook from Gauss PDF.